Rufus Porter, Art, and Enterprise in Portland, Maine

Author’s Note

Rufus Porter was raised on Moose Pond in today’s Bridgton, northwest of Sebago Lake and thirty-eight miles from Portland. In 1804, when Rufus was twelve, his father enrolled him at Fryeburg Academy in Fryeburg, Maine. This private day and boarding school, established in 1792 and still in operation today, was about nine miles west of Porter’s home. Amos Jones Cook (1778–1836), the academy’s progressive headmaster, was an inspirational figure: he published The Student’s Companion, a compilation of works by celebrated authors and poets; employed the power of music in the education of his students; and assembled a renowned cabinet of curiosities for his charges.2 Porter readily found intellectual stimulation in spite of his frontier location. He later fondly recollected that his family’s farm was “beautifully variegated with woodlands, high and steep hills, miry grass-marshes, level plains, sand banks, running brooks, and a small pond; also a large orchard . . . cider-mill . . . mechanical implements of agriculture, and a workshop in which they were made and repaired.” He especially enjoyed “drawing sketches, floating a boat, or running a miniature cart” and “excelled in drawing and music; having made a small fiddle about that time.”3 Tyler Porter’s business operations included a sawmill and the development of a canal in the waterways near Sebago Lake. As a boy, Rufus “learned to construct not only miniature water-wheels and saw-mills, but water-power trip-hammers, and a variety of complicated mechanical movements.” He came into Portland as a teenager “for a season” to work on board ships in the harbor.4

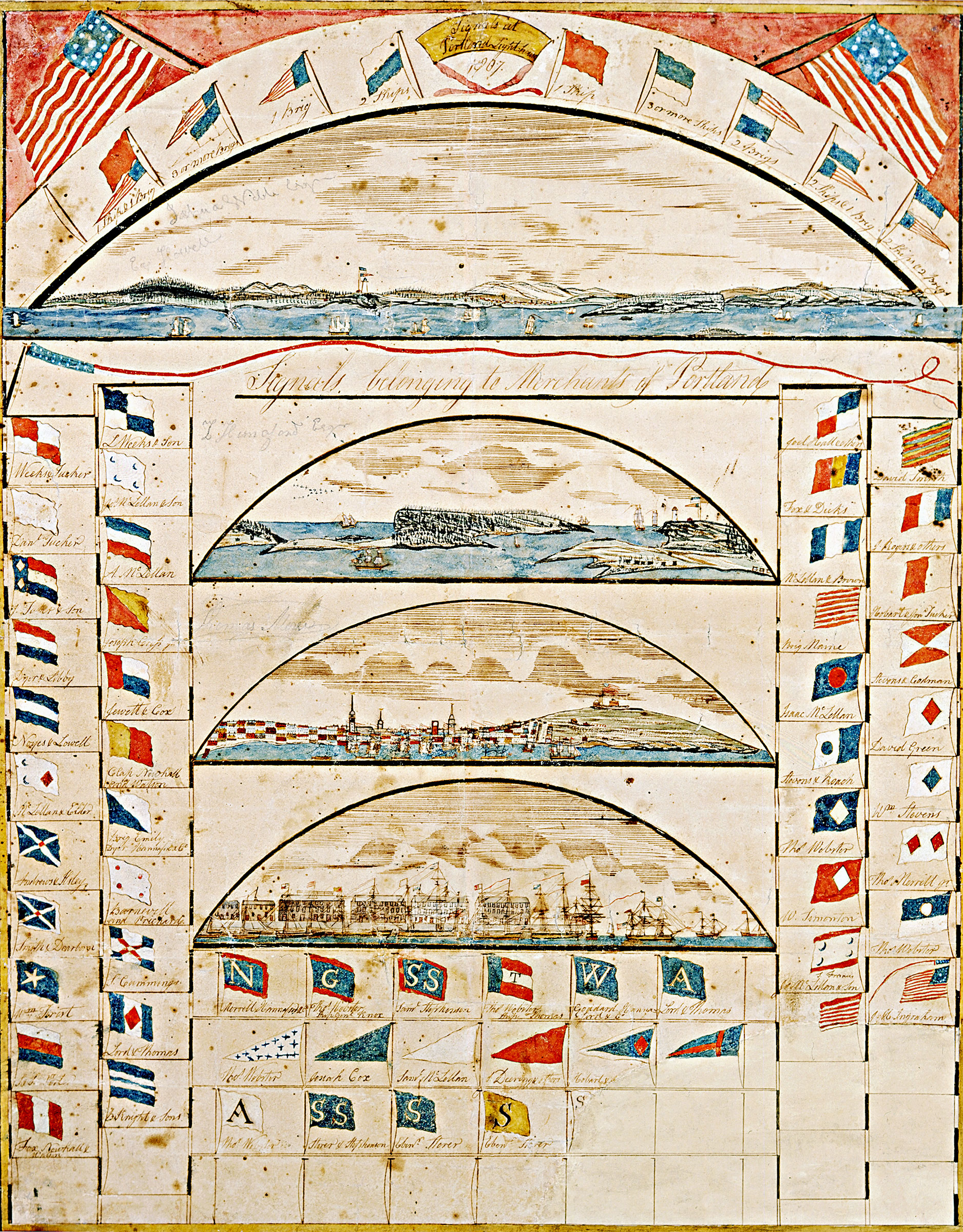

Porter’s move to Portland was a natural progression for the ambitious and talented young man. Like the rest of the district, the town’s population grew dramatically after the Revolutionary War. Familial, commercial, and political networks tied Portland and the rest of Maine to Boston and towns throughout eastern Massachusetts. Commerce, shipping, and shipbuilding drove a booming economy for entrepreneurs and artisans; international trade brought increased prosperity to many. This vitality is captured in Lemuel Moody’s (1761–1846) diagram Signals at Portland Lighthouse (Fig. 1). A retired sea captain, he had devised a signaling system, with flags assigned to different merchants, at the Portland Observatory, an eighty-two-foot-high octagonal tower built in 1807 on Munjoy Hill. He was especially proud of his telescope made by the Dollands, England’s leading optical firm. When he spotted ships offshore, Moody flew the merchants’ flags from the cupola to alert owners of their vessels’ arrival. Moody’s drawing not only identifies the individual flags but also depicts the ship channel and approach to the harbor. While offering an important means of communication for the maritime community, the observatory was a form of entertainment for many others. Moody welcomed visitors to climb to the cupola, at the cost of twenty-five cents, where they were rewarded by views of Casco Bay to the east and the White Mountains, with majestic Mount Washington, New England’s highest peak, seventy miles to the west.5 Munjoy Hill also provided open space for the parade grounds, later depicted by Portland landscape painter Charles Codman (1800–1842) in his Entertainment of the Boston Rifle Rangers by the Portland Rifle Club in Portland Harbor, August 12, 1829 (Fig. 2).

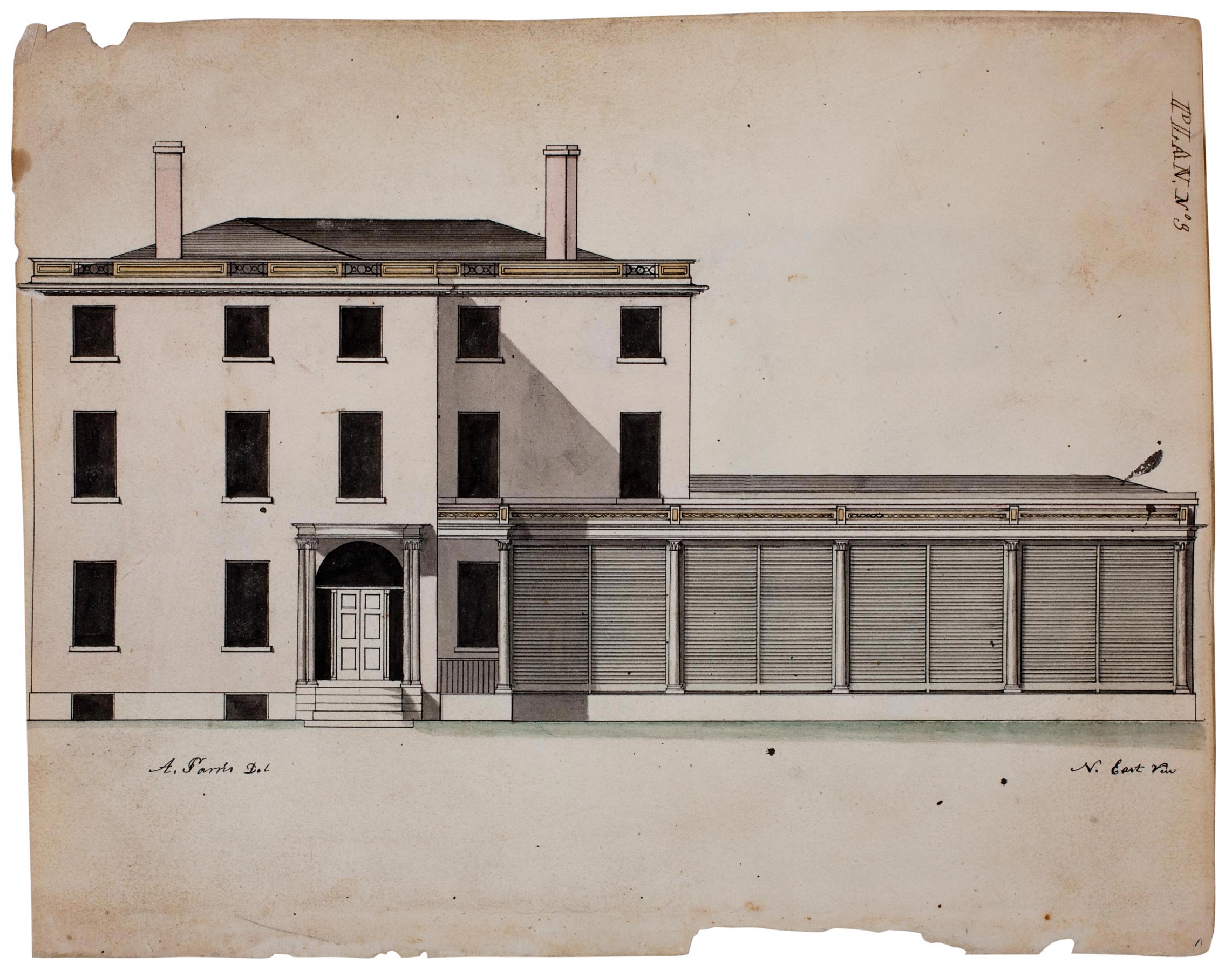

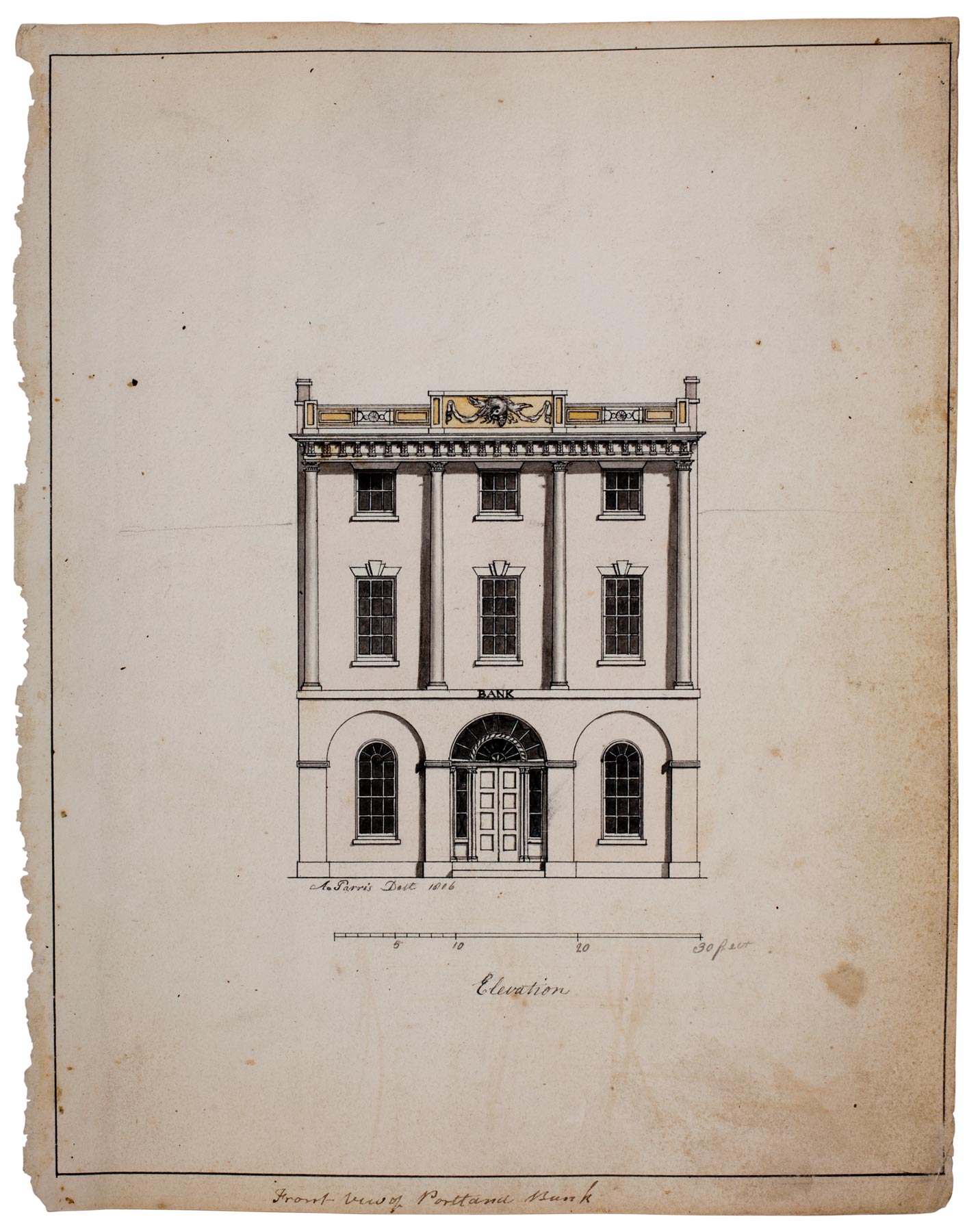

A beloved landmark that survives today, the observatory was constructed as part of Portland’s redevelopment, following the town’s destruction in 1775 by a British naval bombardment. Other new and notable commercial and residential buildings in the Federal style were the work of Alexander Parris, a young architect from Pembroke, Massachusetts, who developed many innovative classical designs for residents. In 1805, Parris designed a three-story brick dwelling with a low hip roof for Commodore Edward Preble (Fig. 3). The home’s entrance faced the side street, enabling a large double parlor to run across the principal Congress Street elevation. Parris’s facade for the Portland Bank, built in 1806, featured semicircular arches on the ground floor with applied pilasters on the upper elevations. Sky-lit interior stairs and groin vaulting made this the town’s most sophisticated example of Federal commercial architecture (Fig. 4). Although immensely talented, Parris faced the financial adversities caused by the embargo of 1807. He soon left to expand his horizons, pursuing a notable architectural career, first in Richmond, Virginia, and then in Boston.6

In addition to improving their built environment, Portlanders also supported civic organizations, including the Maine Charitable Mechanic Association (MCMA), founded in 1815 to educate men whose livelihoods were derived from manual or skilled labor (known as mechanics) and to “promote inventions and improvements in the Mechanic Arts.”7 Marcus Quincy, a town officer, was one of the MCMA’s founders. At his store on the waterfront, he “attend[ed] to the painting business” and is credited with teaching Rufus Porter “the trade of a house painter.”8 Porter recalled that he “commenced learning the house and ship painting . . . [and] was a ready-made sign and ornamental painter.”9 Porter’s endeavors may have further benefited from an extended group of relatives in town, including cousin Aaron Porter (1752–1837), a physician who helped develop Porterfield Plantation in western Maine, incorporated as the town of Porter in 1807. His wife, Paulina King Porter (1759–1833) was the sister of Rufus King (1755–1827), a leading national politician, and half-sister of William King (1768–1834), who became Maine’s first governor. 10

In March 1811, Portland Light Infantry, a private militia company, enrolled Rufus as a new member. Rufus participated in regular musters on Munjoy Hill and target practice in Deering Oaks, part of the Deering estate nearby on Back Cove. He recollected that “being a musician in a first-rate uniform company of infantry, and having been previously for some months in regular service at a fort, I was sometimes employed in teaching a fife and drum school.”11

The Portland artist George Bailey (1832–1905) later depicted the company’s activities in a delightful painting of an encampment (Fig. 5). Within a rural landscape filled with white tents, uniformed militia members mingle with happy spectators. Horses, carriages, and musical instruments can all be seen. A side drum, with decoration attributed to Charles Hubbard (1801–1876) of Boston, illustrates the type of percussion instrument that Porter would have played (Fig. 6). Its painted design depicts the Seal of Massachusetts surrounded by flags and trophies of war.

Company members also inspired Porter in the field of invention and mechanical improvements. John Hancock Hall (1781–1841), its lieutenant, was working on a breech-loading rifle that he patented in 1811. His innovative mechanism enabled more efficient loading of the gun, and his concept of interchangeable parts transformed the early arms industry. After winning a contract with the United States Armory, Hall left Portland in 1819 for Harpers Ferry, Virginia, the site of one of America’s two arsenals and armories, where he produced thousands of rifles between 1820 and 1840. Within fifteen years, Porter would design his own innovative gun mechanism. He never patented his revolving rifle but sold the concept to Connecticut arms manufacturer Samuel Colt in 1836.12

The arts in Portland were on the rise, and exhibitions appeared in temporary venues. At Union Hall, a large exhibition space, residents took in the Bombardment of the City of Tripoli, a sixty-foot long panorama by Michele Felice Cornè (1752–1845), “executed in a masterly stile,” according to local newspapers.13 Italian-born, Cornè immigrated to Massachusetts in 1800. From his base in Salem, he found patronage for his portraits, decorative wall murals, and other works. Celebrating the young United States Navy’s achievement in the First Barbary War, the scene was especially meaningful for Portland because native son Edward Preble had commanded the fleet, defeating the Barbary pirates in 1803. The panorama was initially available for viewing in April 1807, probably only for a few weeks.14 Its popularity, however, warranted a return visit and it was on view again in July 1808.15 Preble had commissioned his own painting of the bombardment from Cornè in 1805 (Fig. 7), which furnished his neoclassical residence designed by Alexander Parris (Fig. 3).

In 1816, Stowell and Bradley advertised their Elegant Museum, a temporary exhibition where Portlanders marveled at a life-size wax statue of George Washington, a “Temple of Industry; or Grand Mechanical Panorama” with dozens of moving figures, and landscape views by the “most eminent American artists.”16

Local residents also increased their patronage of individual artists. Those who traveled, such as sea captains or legislators, might embrace an opportunity to have their portraits taken while away. For example, Captain Joseph McLellan, Sr. commissioned Henry Sargent (1770–1845) of Boston to paint his portrait in 1798.17 For residents based in Portland, itinerant artists offered a variety of styles at a wide range of prices, from as much as one hundred dollars for an oil portrait to twenty-five cents for a cut-paper silhouette. Itinerant artist John Roberts (1769–1803) advertised in Portland’s newspapers from August 1801 to March 1803, offering full-sized and miniature portraits in addition to ceremonial Masonic aprons. A native of Scotland, Roberts pursued a multifaceted career as an artist, engraver, and inventor following his immigration to America in 1793. He painted the portrait of Elizabeth (Betsy) Wadsworth in October 1801 on a fine sheet of ivory (Fig. 8). In a letter to a friend, her sister Zilpah asked, “Should you like to see Betsy’s miniature? I hope to have it in my power to show you a very good likeness though I cannot say as yet how good it will be, for it is not finished. It is taken by Roberts.”18

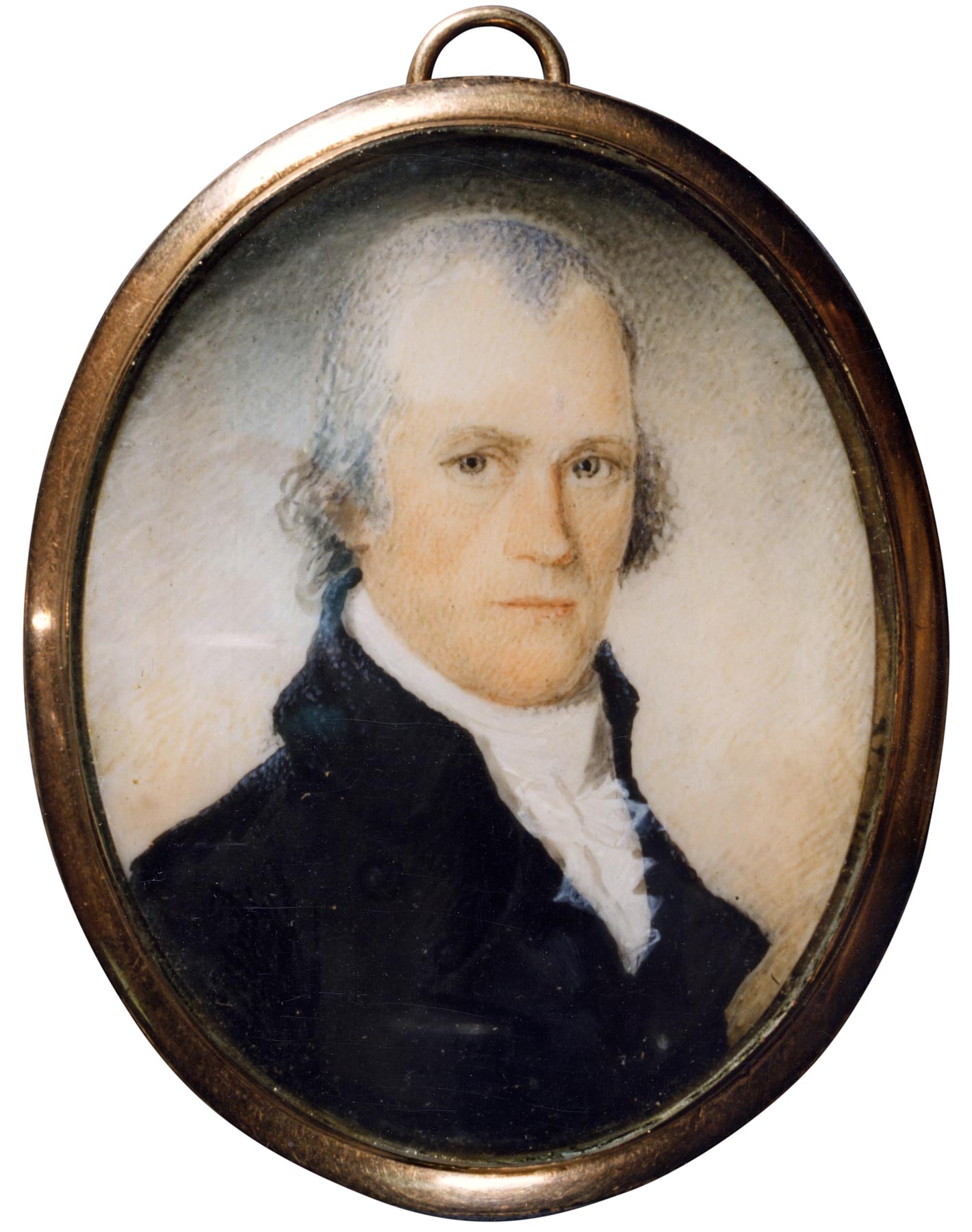

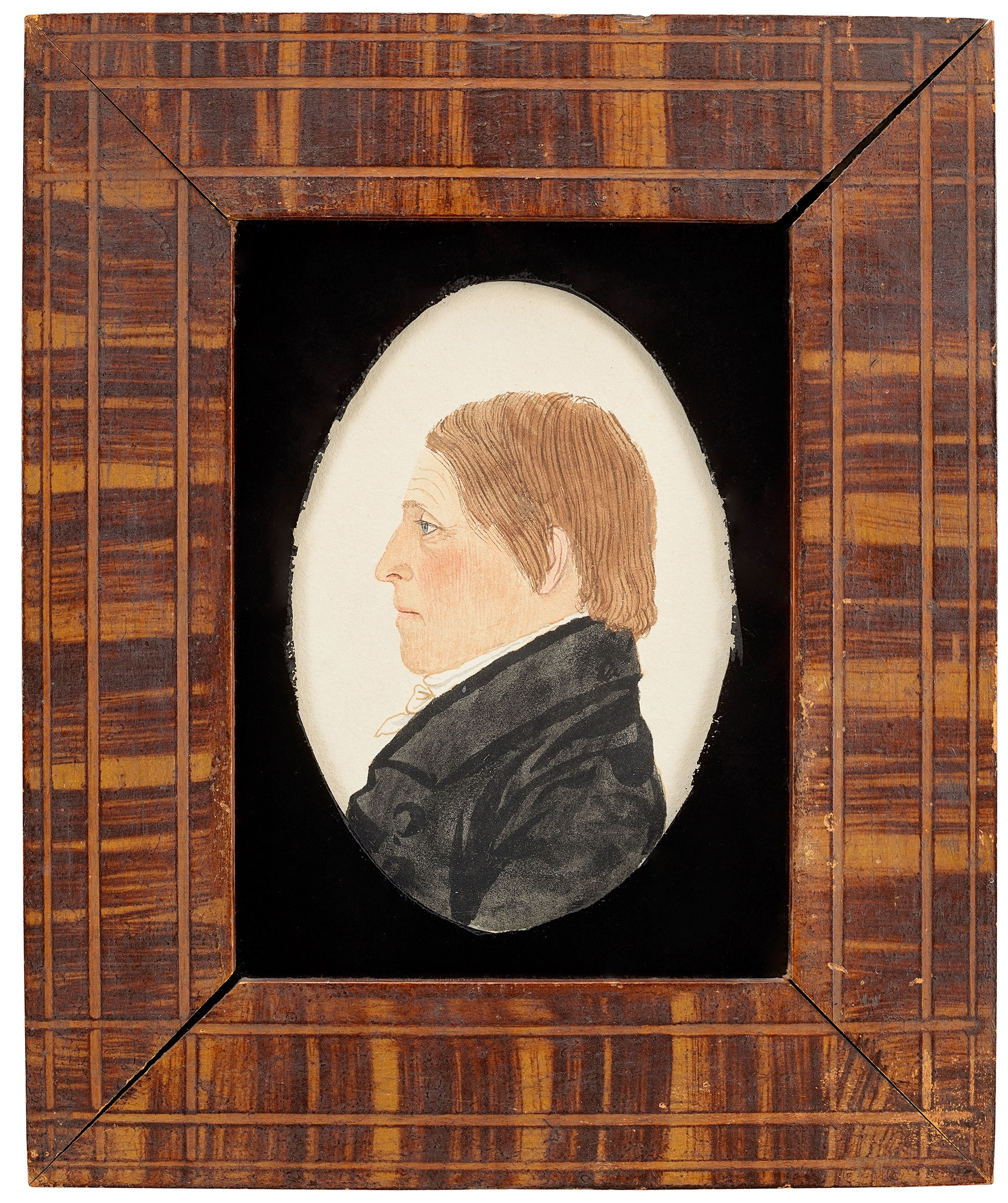

In a newspaper advertisement, Roberts offered a reduced price of ten dollars for three miniatures if taken together.19 He likely painted the portrait of Stephen Longfellow, Betsy’s betrothed, at the same time (Fig. 9).20 Roberts’s work is noted for his simplified depiction of dress and his large, distinctly drawn eyes. Sadly, Betsy Wadsworth died of consumption before she and Stephen could be married, but her likeness remained as a treasured memorial.

Shipbuilder John Quinby (1758–1806), a successful merchant in the Atlantic trade (Fig. 10), commissioned an as-yet unidentified artist with a more refined style to paint his miniature-on-ivory portrait.

Portlanders also took advantage of silhouette cutters, who offered an inexpensive way to capture a likeness. William King (working 1804–1809), from Salem, Massachusetts, visited Portland in 1805, advertising that he had “taken about 10,000 likenesses in Salem, Newburyport, Portsmouth, & their ajoining [sic] town.” A pair of silhouettes celebrated the union of Stephen Longfellow and Zilpah Wadsworth, who were married in 1804, following Betsy’s death (Fig. 11). He embossed the paper “W. King” below the shoulder of the sitter. In hollow-cut, or negative, profiles, such as these, the silhouette was cut from white paper and placed over a black background. Some silhouettists cut a positive image instead, applying a solid profile to a contrasting ground. King advertised that he used his “patent delineating pencil.” His fee was twenty-five cents to create two profiles of the same person, and his special mechanical device likely sped his task. Zilpah’s parents, Elizabeth and Peleg Wadsworth, likewise commissioned silhouettes at this time, perhaps taking advantage of the group discount that King also offered.21

John Brewster, Jr. (1766–1854), an artist from nearby Buxton, and several yet-to-be identified artists created compelling portraits—full size in oil on canvas or miniatures on ivory. In 1806, Brewster advertised in the newspaper and many of his portraits of Portlanders are known.22 He was another artist who used mechanical devices to help speed the process and improve the accuracy of the likeness.23 In 1806, John Quinby’s son Moses (1786–1857) graduated from Bowdoin College, twenty-seven miles north of Portland. Maine’s first, the college was established in memory of James Bowdoin II, former governor of Massachusetts, with the aid of his son, James Bowdoin III, expressly to educate Maine residents. Following his graduation, Moses returned to Portland to study law with Stephen Longfellow. He inherited his father’s estate after John’s death in September 1806, and, as a young attorney, commissioned his waist-length oil-on-canvas portrait from Brewster (Fig. 12). Brewster depicted him neatly attired in a forthright, focused way. His was one of three Quinby oil portraits attributed to Brewster that were still on view in the family’s historic Stroudwater homestead in the early twentieth century.24 One of Brewster’s rare miniatures depicts Harvard College-educated Prentiss Mellen (Fig. 13), who had settled in Portland by 1806 and built a new house on State Street, another of Alexander Parris’s elegant Federal-style dwellings. Early in his law career, Mellen was a circuit rider; he later served as a legislator and eventually became chief justice of the new state in 1820.25

Several Massachusetts-based artists gained important Portland commissions. For example, James Akin (c. 1773–1846), an engraver from Newburyport, created the membership certificate for the Portland Marine Society in 1807. Composed of foliate cartouches of maritime scenes, Akin’s design is closely related to Joseph Callendar’s 1789 engraving for the Boston Marine Society.26 Two years earlier, in 1805, Akin had engraved A Perpetual Almanack for Gardner Goold, Porter’s neighbor in Pleasant Mountain Gore. This large engraving clearly presented vital daily information—days of the week, sunrise, and sunset. It likely inspired Porter, who developed the especially innovative Revolving Almanack after he moved to Boston.27 The Stroudwater Light Infantry Company, another of Portland’s private militias, also commissioned an out-of-town Massachusetts artist for their new silk banner (Fig. 14a). Given its exceptional quality, the painter was likely Boston-based, possibly John Ritto Penniman, one of New England’s most accomplished ornamental painters. In 1805, Eunice Quinby (1783–1862), daughter of John Quinby, presented it to the company. On the obverse, a soaring eagle with a shield, clutching arrows and an olive branch, is inscribed “Presented to the Stroudwater Light Infantry / From the Fair to the Brave.” The custom of ladies (the Fair) presenting banners to militia companies is well documented in early America.28 The reverse features the Seal of Massachusetts enclosed by its official motto: Ense Petit Placidam Sub Libertate Quietem (By the sword we seek peace, but peace only under liberty, Fig. 14b). Rufus Porter may have known and, as the accomplished painter he was, admired this important Portland banner.

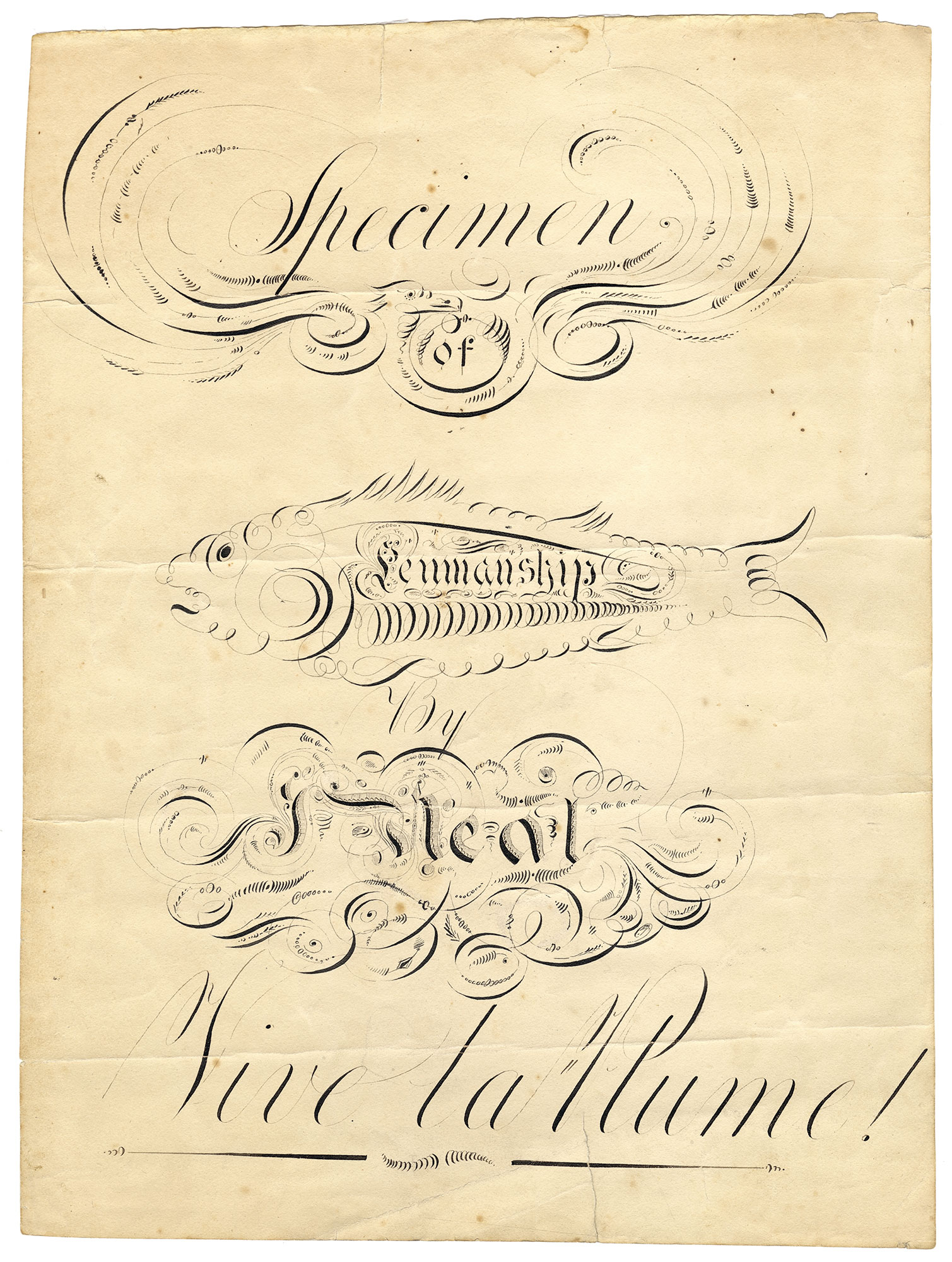

In 1807, Congress passed the unpopular Embargo Act, prohibiting shipping and trade with Britain and France, and Portland’s commercial progress was temporarily curtailed. Even in these tough economic conditions, young artists and entrepreneurs sought ways to generate income by their talents. As a teenager, John Neal (1793–1876), one of Porter’s contemporaries, excelled at penmanship and maintained merchants’ ledger books.29 After meeting traveling penmanship master William W. Rockwell in 1811, Neal traveled to Bowdoin College and central Maine, giving penmanship and watercolor lessons and creating ink portraits.30 With his Specimen of Penmanship, c. 1813—inscribed “Vive la Plume!”—Neal celebrated creativity while engaging potential clients (Fig. 15). This ambitious young man soon left Maine to promote American artists, including Washington Allston (1779–1843) and Samuel F. B. Morse (1791–1872), and published America’s first art criticism in Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine in 1824 and 1825.31

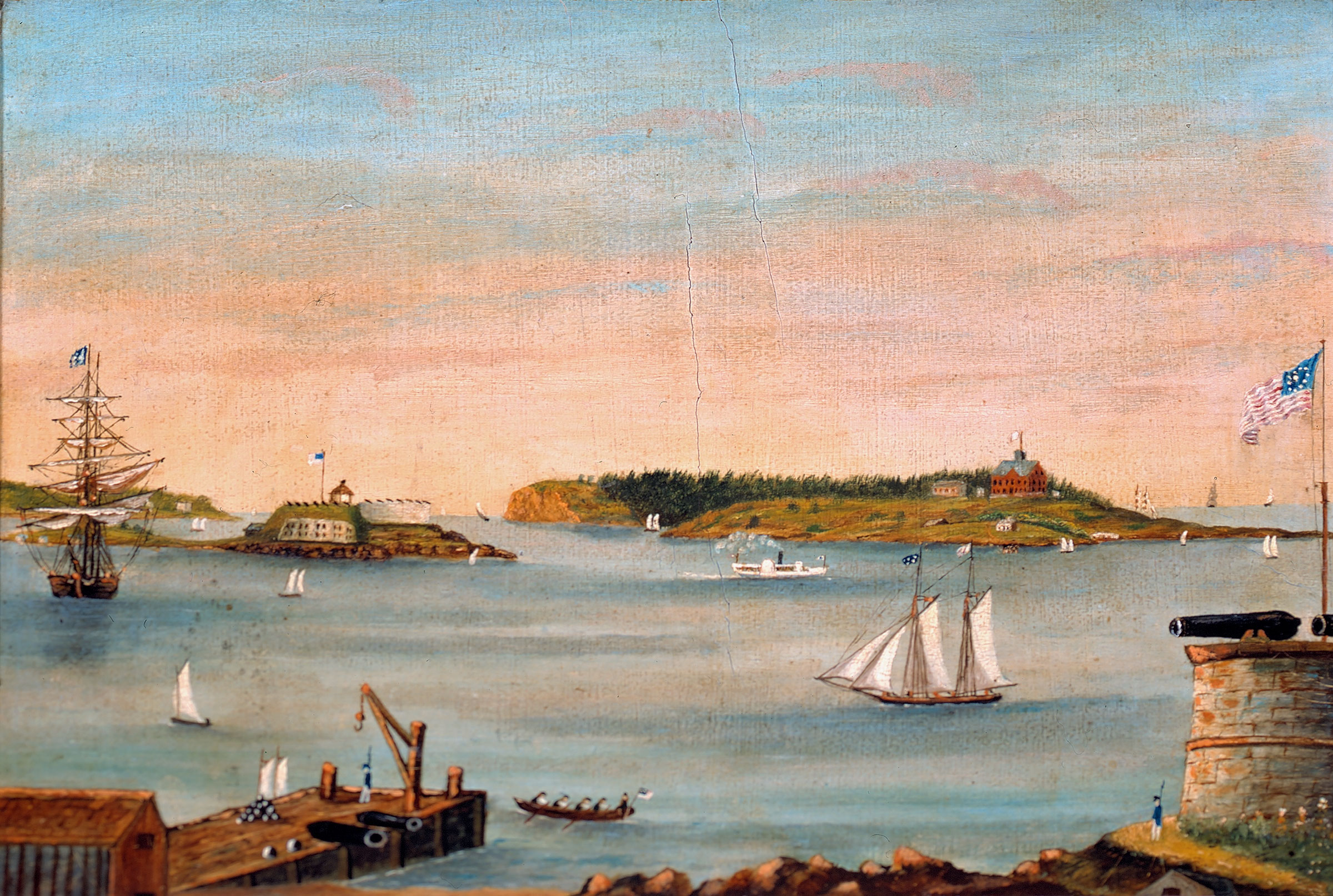

Many years of Porter’s residency were dominated by activities related to the War of 1812. During this anxious time, Portland struggled to get Massachusetts to send military support, a major factor in residents’ renewed push for statehood after peace was declared late in 1814. Hundreds of militia volunteers moved in and out of Portland, serving short terms in companies. They improved two state forts: Fort Sumner on Munjoy Hill, just north of the observatory, and Fort Burrows below, at Fish Point on the Fore River. Alexander Parris superintended the construction of two new federal forts—Preble and Scammel—that guarded the ship channel. A painting of Portland’s harbor illustrates how these structures appeared before they were enlarged in 1862 (Fig. 16). Fort Preble, honoring Commodore Edward Preble, who died in 1807, was on the south side of the Fore River near shipyards. Fort Scammel, named for Alexander Scammell, a Revolutionary War hero, is visible on the island at the center of the picture.32 Volunteer militiamen worked on these forts, and others served on privateers that forayed from the port.

This may have been when Porter was “employed on board armed vessels,” and as he recollected, “I acquired some knowledge of marine discipline, as well as sailor’s duty.” 33 During the war, the British invaded and occupied Castine in Penobscot Bay, a twenty-four-hour sail to Portland. Their skirmishes in other coastal towns raised a serious threat to Maine, and Portland prepared for war. Porter served as musician and played the fife and drum in Captain Nathaniel Shaw’s company, Lieutenant Colonel M. Nichols’s regiment. Raised at Portland and serving from September 7 to 19 and again from September 26 to October 3, 1814, it included members of the Portland Light Infantry. Later that fall, from November 5 to 26, 1814, Porter served again as a musician with Lieutenant Oliver Bray’s detached company at Fort Burrows.34 This palisaded structure is visible in the lower right of Codman’s encampment painting (Fig. 2).

Portlanders, Porter among them, personally experienced one of the war’s most dramatic naval engagements. On September 5, 1813, the brigs USS Enterprise and HMS Boxer engaged in battle off the coast of Maine, resulting in a stirring American victory. Tragically, however, the young American and British captains were both mortally wounded. The damaged ships were brought into Portland harbor, and the town arranged a double funeral. On September 9, following an elaborate cortège, the captains were buried side-by-side in the Eastern Cemetery on Munjoy Hill. As a militia musician and member of Captain Shaw’s company, Porter may well have participated in the solemn military procession.35

After peace was declared on Christmas Eve 1814 with the Treaty of Ghent, cultural activities resumed. Porter’s militia experiences inspired his first known attempt in publishing, “Martial Musician’s Companion,” a compendium of instructions for the drum and fife. While looking for a collaborator, he wrote to Charles Norris in February 1815. Norris was the same New Hampshire publisher who Porter’s headmaster, Amos Cook, had corresponded with a few years earlier, and Cook likely made the referral. Although Porter secured his copyright, he was unable to negotiate the book’s financing, and it was never printed. This failure did not discourage his future efforts, however, for in another five years Porter found support for his first arts manual, A Select Collection of Valuable and Curious Arts, known familiarly as the Curious Arts, published in Concord, Massachusetts, in 1820–1821.36

A new book of particular interest to Portlanders was Abel Bowen’s The Naval Monument, his major work of 1816 that commemorated American achievements during the War of 1812. Bowen created engravings of the principal battles, including the Enterprise and Boxer, based on oil paintings by Michele Felice Cornè. In the years ahead, Abel and his brother Henry Bowen would collaborate with Porter on some of his new endeavors.37

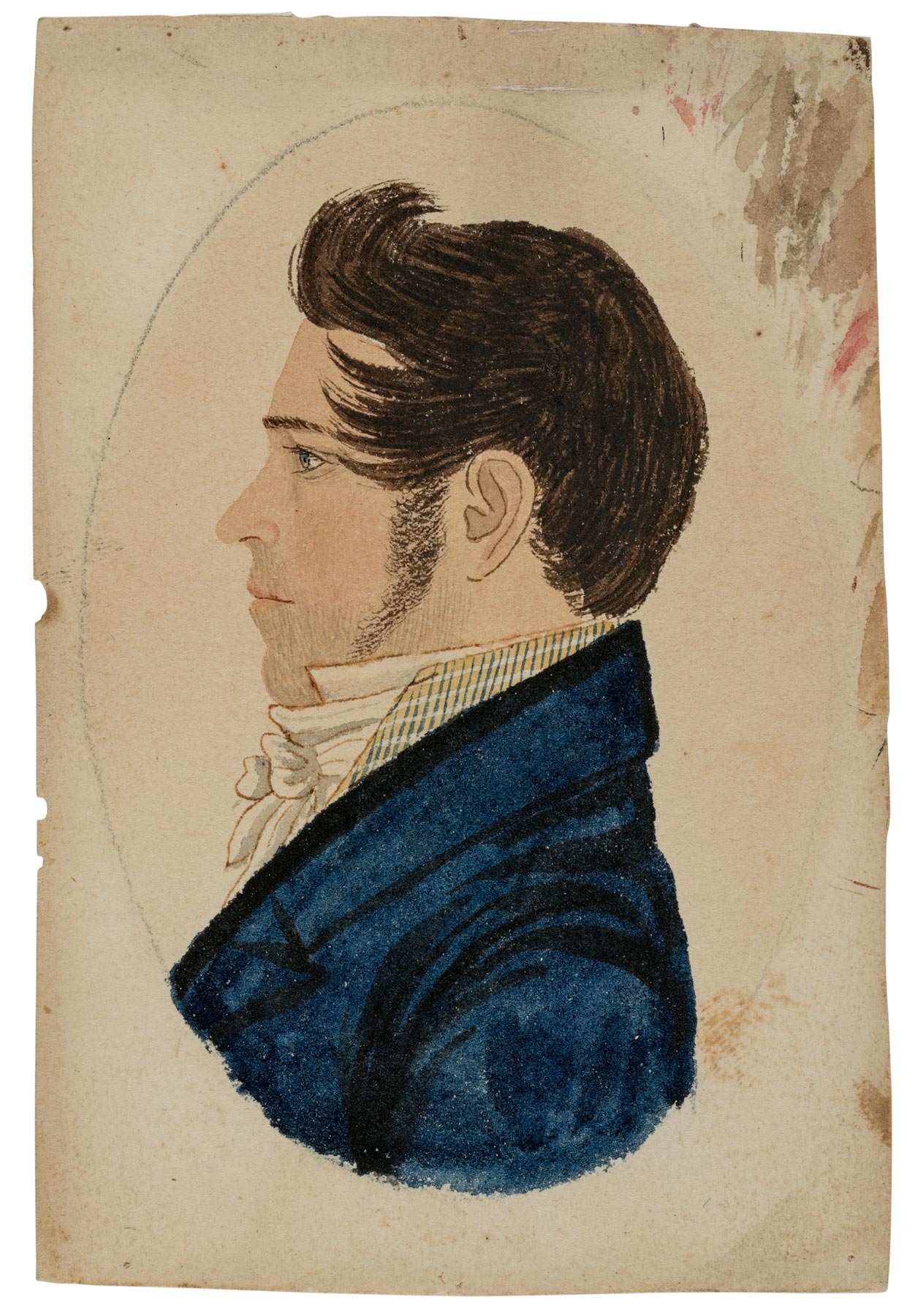

Itinerant artists returned to Portland. English-born William Bache (1771–1845) immigrated to Philadelphia about 1793 and later worked in many cities on the East Coast. From February to May 1815, he advertised his services in Portland. He cut the likeness of Francis Douglas (c. 1783–1820), editor of the Eastern Argus, one of the papers in which Bache’s notices appeared. Perhaps he bartered the profile in exchange for his published notices (Fig. 17). The negative-cut white-paper profile was placed on a black ground. He added brushed details to the hair, and white highlights delineate the shirt ruffle and coat. Bache also took the profile of Mary Louisa Deering (1805–1878), daughter of James Deering (Fig. 18). Its negative cut is highlighted in the same way, with painted details of her hair, tendrils around her face, and a ruffled collar. Both works bear his embossed mark, “BACHE’S / PATENT,” on the lower edge of the shoulder.38 Two small watercolor portraits of Seth Clark (1783–1871) and Mary Owen Elder (1802–1838), accomplished works on ivory by unidentified artists, reveal the level of quality that Portlanders sought (Figs. 19, 20). After his War of 1812 service, Clark helped establish the MCMA and became the town’s first merchant tailor. His account book reveals many of his clients, including Amos Cook and Prentiss Mellen, but not the painter who captured a compelling likeness of an engaging young man. Clark is set off on a light blue ground, nattily dressed in a blue coat and red waistcoat. Taken in a three-quarter view, Elder, the daughter of a baker, is attired in a high-waisted white dress typical of the period, complete with decorative blue sash, red shawl, and curled hair held by a comb.39

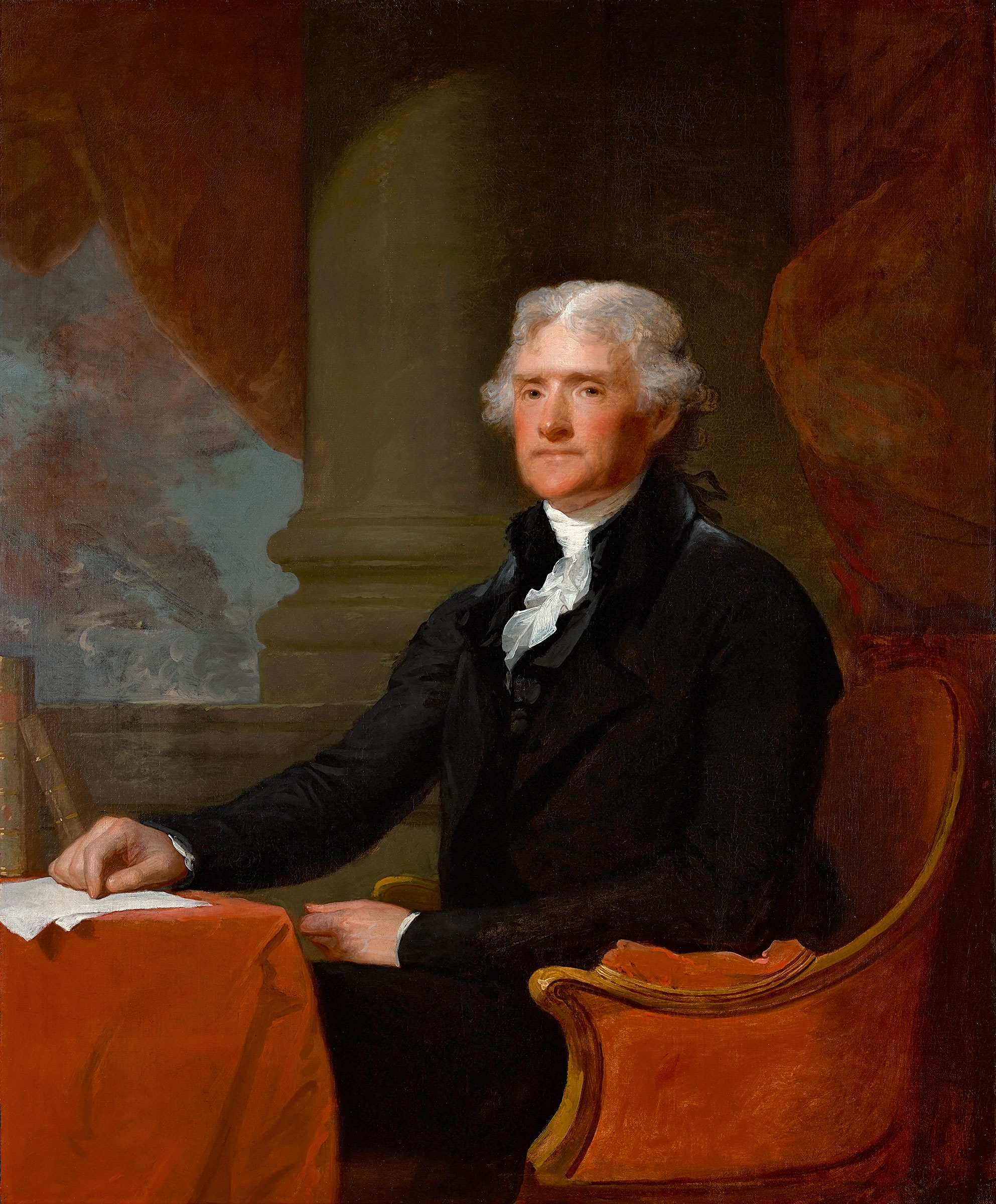

Among the artists coming and going in the seaport, Moses Pierce (c. 1783–c. 1844) was unusually enterprising between 1815 and 1818. Pierce’s early career, from 1806 to 1812, is recorded in Quebec, where he worked as a coach and sign painter. He returned to the United States in 1812, probably at the outbreak of the war, when Americans were ordered to leave Canada. He advertised in Portland in October 1815, seeking patronage for his portraits, worked in oil colors, and expected “to tarry here for a short time.”40 In 1817, Pierce disappeared from the published notices, as many itinerant artists do. However, when he reappeared in 1818, he made an unusual announcement. He had been away, “having spent the past year in studying the most celebrated Paintings in the Gallery of Bowdoin College.”41 James Bowdoin III, a retired diplomat, had assembled an art collection comprised of over seventy European and American paintings, which he bequeathed to Bowdoin College in 1811. They were on view in Massachusetts Hall, the college’s first building, by 1813. A three-story brick structure crowned by a cupola, it is depicted in the earliest known view of the campus (Fig. 21), by John G. Brown (d. 1858). Works that Pierce would have seen ranged from European old masters to those by living American artists. For example, a painting attributed to the Flemish artist Frans Francken III (1607–1667), Achilles at the Court of Lycomedes, c. 1650, was exhibited along with Gilbert Stuart’s (1755–1828) 1805–1807 portrait of Thomas Jefferson (Figs. 22, 23).

Another notable work was the copy of Nicholas Poussin’s 1640 Continence of Scipio (Fig. 24) by John Smibert (active in America, 1728–1751). The painting tells the story of the Roman general Scipio, who, despite his fabled lasciviousness, returned a captive to her fiancé rather than enslaving her. Providing a meaningful example of gracious leadership, the painting was likely used to instruct students academically, artistically, and morally in the early years of the college. Born in Scotland, Smibert trained in London, traveled in Europe and to Bermuda, and finally settled in Boston in 1729. He became the first professionally trained portraitist in the American colonies. Copying old masters had been a vital component of an artist’s education since the Renaissance, and Smibert copied Poussin’s celebrated painting while studying in England. He is known to have assembled old master drawings and paintings that he brought to Boston when he immigrated. After Smibert’s death in 1751, his family kept much of the collection intact in his studio where it continued to inspire American artists, including John Singleton Copley and Washington Allston. James Bowdoin III purchased part of Smibert’s collection in the late eighteenth century, and with his bequest to the college established one of the first public art collections in America.42

Remarkable works by American artists also graced Massachusetts Hall, including Bowdoin’s family portraits by Robert Feke (active 1741–1750) and Joseph Blackburn (active in America 1754–1763). Bowdoin’s gift of major works by Gilbert Stuart included the companion portrait to Thomas Jefferson, then president of the United States, that of James Madison, his secretary of state. Possessing a keen intellect and prodigious talent, Stuart studied under Benjamin West in England in the late 1770s. On his return to America, he gained fame for his state portraits of Washington and other American leaders. Bowdoin commissioned the portraits of Jefferson and Madison around 1805. Jefferson had appointed Bowdoin America’s ambassador to Spain, where he planned to use the large pictures in his formal reception rooms. However, Stuart was slow to finish the portraits, and, when Bowdoin’s tenure was cut short by the Napoleonic Wars, the portraits remained in Boston.43 Since their arrival in Brunswick in 1813, they have remained treasures of the Bowdoin College collection.

Having copied many of these works, Moses Pierce displayed his collection of paintings at the Portland Bank, where Alexander Parris’s design provided spacious accommodations (Fig. 4). Pierce’s “Gallery of Paintings,” advertised in the Eastern Argus, is the earliest known reference to a Portland artist operating a commercial art gallery. His paintings were on view for two months; he then moved them to his house, where they remained available for the public to see.44 He still offered his services for oil portraits, ranging in price from thirty to one hundred dollars, the upper price being what Gilbert Stuart, America’s premier portraitist, charged.45 Perhaps discouraged by the lack of interest by Portlanders (were his prices too high?), Pierce soon sought patronage in other towns, including Portsmouth, New Hampshire, Providence, Rhode Island, and Hartford, Connecticut. Depictions of his Portland sitters have not been identified. Fortunately, Pierce’s New England work is known through a portrait of Susanna West Sweetser (1786–1861), of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, signed and dated 1819 (Fig. 25). He worked in a distinctive style with soft features and delicate details.

All this artistic activity must have inspired and encouraged Porter, a naturally gifted painter, to take up his brush and give small watercolor portraits a try. He also had a family to support; he married Eunice Twombly (1794–1848) in October 1815, and their first child, Stephen Twombly Porter, was born the next summer.46 Miniatures of Maine sitters attributed to Rufus Porter were first identified in 2007, when portraits of Benjamin Lane (1777–1846), his wife, Hannah (1780–1867), and a child were sold at an estate auction (Figs. 26, 27, 28). Porter’s earliest known family group, the Lanes lived in Minot, a farming community north of Portland. With one backboard inscribed “Rufus Porter” in chalk, art historian Deborah Child linked these portraits to the body of Porter work she was documenting. 47 Her essay “Rufus Porter’s Miniature Portraits: Practice and Patrons,” in Rufus Porter’s Curious World, builds on this research. Three additional miniatures of Maine sitters have recently been identified: Jacob Davis (1791–1864), Thomas Long (1798–1841), and his older sister, Betsey Long (1796–1867). Davis, like Porter and Benjamin Lane, served in the Massachusetts volunteer militia in Portland in 1814 (Fig. 29). One year older than Porter, Davis was a corporal in Captain Bridgham’s company and Lieutenant Colonel Clark’s regiment in Portland from September 1 to 24, 1814, at the same time that Porter served there.48 Davis also lived in Minot, like the Lanes. Thomas Long became an accomplished musician in the United States Navy. He and Betsey Long were from Buckfield, fifty-five miles north of Portland (Figs. 30, 31). Porter deftly captures confident likenesses, with his sitters exuding a special poise and vitality. Careful looking reveals details of Porter’s technique in these early works: a fine brown undulating line delineates the men’s ties and the ladies’ collars; broad color washes similarly appear on the dresses and coats; and fine striations create hair styles. Often, test brush strokes remain in the margins where Porter checked the color and viscosity of his paint. Remarkably, the reverse of all six portraits retain remnants of a cursive inscription in red ink, indicating they were likely cut from the same sheet of paper. Were they created about the same time, when these mutual friends or acquaintances were together before returning to their hometowns? Four of the six works—the three Lanes and Betsey Long—retain their original grain-painted frames, likely the handiwork of Porter himself. 49

One of Porter’s last known Portland endeavors was the construction of his horizontal windmill. This project foreshadowed his later entrepreneurial efforts to promote mechanical invention through stock companies. Built on Green Street at the top of today’s Forest Avenue, the site of earlier windmills, Porter’s was completed in the summer of 1818. In this mechanical innovation, the mill’s sails, supported on a frame, moved parallel to the ground. 50 Porter may have drawn inspiration from English examples, such as the one published in The Repertory of Arts and Manufactures in London in 1796. Merchant Bradbury C. Atwood, Porter’s collaborator, advertised shares of stock in the enterprise. The local press reported that the windmill successfully “manufactured excellent meal” and Porter later observed that it was “so constructed as to be manageable by a child of 12 years of age.” 51 Porter honored his partner when he named his daughter, born that July, Mary Bradbury.

However, after the mill was badly damaged in a storm, Porter was unable to repair or sell it. Discouraged by this, he soon sought greener pastures, relocating to Cambridge, Massachusetts, by February 1820. 52

During nearly a decade in Portland, Porter embraced painting, invention, and publishing—three fields that he diligently pursued in the decades ahead. The town’s diverse and talented pool of artists, mechanics, and entrepreneurs not only helped him advance these interests but inspired him in his early efforts. Porter, like his notable contemporaries John Hall, John Neal, and Alexander Parris, found initial patronage, honed his skills, and developed the confidence to move on to larger markets and seek new opportunities. With a new understanding of Porter’s life in Portland, it is hoped that continued research on his activities—and attribution of additional early watercolor portraits—will shed further light on the depth and influences of his Maine experiences.

Acknowledgments

About the Author

1 Laura Fecych Sprague, “Rufus Porter: A Life in Motion,” in Rufus Porter’s Curious World: Art and Invention in America, 1815–1860, ed. Laura Fecych Sprague and Justin Wolff (Brunswick, ME: Bowdoin College Museum of Art in association with the Pennsylvania State University Press, 2019), 15–16.

2 Ibid., 15–17.

3 Rufus Porter, “Epitome of Experience and Practice,” Aerial Reporter, April 27, 1854, reprinted in Sprague, Rufus Porter’s Curious World, 121–24.

4 Sprague, “Rufus Porter: A Life in Motion,” 15; Porter, “Epitome,” 121, 123.

5 Laura Fecych Sprague, ed., Agreeable Situations: Society, Commerce, and Art in Southern Maine, 1780–1830 (Kennebunk, ME: The Brick Store Museum, 1987), 46–48, cat. nos. 7–8. Moody owned Dolland’s achromatic refracting telescope. See John K. Moulton, Captain Moody and His Observatory (Falmouth, MA: Mount Joy Publishing, 2000), 20, 23, 30–31.

6 Richard Candee, “‘The Appearance of Enterprise and Improvement’: Architecture and the Coastal Elite in Southern Maine,” in Sprague, Agreeable Situations, 83–84.

7 Constitution and History of the Maine Charitable Mechanic Association (Portland: Bryant Press, 1965), 3. Porter was not a member but would have benefited from its mission.

8 “A Rare Mechanic,” Portland Bulletin, October 6, 1846. Quincy’s election as tithingman was reported in the Eastern Argus, November, 24, 1810.

9 “Epitome,” 122–23.

10 Sprague, “Rufus Porter: A Life in Motion,” 16. See also Joseph W. Porter, A Genealogy of the Descendants of Richard Porter, Who Settled at Weymouth, Mass., 1635, and Allied Families: Also Some Account of the Descendants of John Porter (Bangor, ME: Burr & Robinson, 1878), 285–87.

11 Porter, “Epitome,” 123. The page with Porter’s signature from the Portland Light Infantry’s record book is illustrated in Sprague, Rufus Porter’s Curious World, 20. The original is held at the Maine Historical Society.

12 Sprague, “Rufus Porter: A Life in Motion,” 19–20, 25–26.

13 Sprague, Agreeable Situations, 36–37, cat. no. 1.

14 “Panorama,” Eastern Argus, April 9, 1807.

15 “Portland Museum,” Eastern Argus, July 28, 1808.

16 “To the Patron of the Arts,” Eastern Argus, December 10, 1816.

17 The McLellan portrait is in the collection of the Portland Museum of Art, 1972.71.

18 Zilpah Wadsworth to Nancy Doane, October 18, 1801, Wadsworth-Longfellow Papers, Longfellow National Historic Site, Cambridge, MA. Reproduced in Sprague, Agreeable Situations, 123–24, cat nos. 42A–42B.

19 Roberts advertised the discount in the Portland Gazette, March 29, 1802.

20 Sprague, Agreeable Situations, 123–24, cat nos. 42A–42B.

21 Ibid., 207–8, cat. no 126. Skilled and day laborers earned one dollar per day. Twenty-five cents would have been less significant for a professional or member of the merchant class.

22 Others included Reverend Samuel Deane and his wife, Eunice Pearson Deane. See Sprague, Agreeable Situations, 89–91, cat. no. 29.

23 Deborah M. Child, “Rufus Porter’s Miniature Portraits: Practice and Patrons,” in Sprague, Rufus Porter’s Curious World, 60.

24 Henry Cole Quinby, Genealogical History of the Quinby (Quimby) Family in England and America (Rutland, VT: Tuttle, 1915), 286–89.

25 Sprague, Agreeable Situations, 91–92, cat. no. 30; Child, “Rufus Porter’s Miniature Portraits,” 57–58.

26 Sprague, Agreeable Situations, 48–49, cat. no. 9.

27 Child, “Rufus Porter’s Miniature Portraits,” 16, 26–27.

28 Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, “‘From the Fair to The Brave’: Spheres of Womanhood in Federal Maine,” in Sprague, Agreeable Situations, 222–23.

29 Benjamin Lease, That Wild Fellow John Neal and the Literary Revolution (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1972), 11; John Neal, Wandering Recollections of a Somewhat Busy Life: An Autobiography (Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1869), 38, 132, 185.

30 Penmanship services advertised in Portland Gazette, April 29, 1811.

31 Neal’s Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine reviews from August 1824 to February 1825 are reprinted in Observations on American Art: Selections from the Writings of John Neal (1793–1876), ed. Harold Edward Dickson (State College, PA: Pennsylvania State College, 1943), 26–37.

32 Sprague, Agreeable Situations, 52–53, cat. no. 12. Kenneth Thompson, an historian of Portland’s early forts, kindly assisted with this research. He argues that although Fort McHenry in Baltimore is more famous, the Portland forts were important deterrents, helping keep the British at bay. Jamie Rice at the Maine Historical Society also shared helpful insights.

33 Porter, “Epitome,” 122.

34 Sprague, “Rufus Porter: A Life in Motion,” 49n48.

35 Sprague, Agreeable Situations, 54, cat. no. 13. A description of the procession appeared in the Eastern Argus, September 9, 1813. See also Candace Kanes, “Enemies at Sea, Companions in Death,” Maine Memory Network.

36 Rufus Porter to Charles Norris, February 16, 1815; Copyright notice for “Martial Musician’s Companion,” January 24, 1815; Amos Cook to Charles Norris, September 24, 1812, Charles Norris Papers, Mss. 11, New England Historic Genealogical Society, Boston. See also Sprague, “Rufus Porter: A Life in Motion,” 21–22, 24.

37 Abel Bowen, The Naval Monument: Containing Official and Other Accounts of All the Battles Fought Between the Navies of the United States and Great Britain During the Late War (Boston: George Clark, 1816). Within weeks of its publication, on June 25, 1816, the Portland Gazette and Maine Advertiser carried advertisements for it from Portland booksellers. For Bowen-Porter collaborations, see Sprague, “Rufus Porter: A Life in Motion,” 26–28.

38 Sprague, Agreeable Situations, 208–9, cat. no. 127.

39 Seth Clark, business ledger, 1815–1834, Coll. 4061, Maine Historical Society, Portland.

40 Advertisement, Eastern Argus, October 15, 1815. William David Barry kindly brought Moses Pierce’s activities to the author’s attention. See William David Barry, “Artists at Portland, Maine, 1784–1835: An Updated List of That Compiled for the Portland Museum of Art, 1976,” 2007, S.C. 1139, Maine Historical Society, Portland; Lydia Foy, “New England and New York Portrait Makers in Canada, 1760–1860,” in Painting and Portrait Making in the American Northeast, ed. Peter Benes and Jane Montague Benes (Boston: Boston University, 1994), 114–15.

41 Advertisement, Eastern Argus, October 6, 1818.

42 Richard H. Saunders, John Smibert: Colonial America’s Portrait Painter (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1995), 210–11; Susan E. Wegner, “Copies and Education: James Bowdoin’s Painting Collection in the Life of the College,” in The Legacy of James Bowdoin III (Brunswick, ME: Bowdoin College Museum of Art, 1994), 141–42.

43 Marvin Sadik, Colonial and Federal Portraits at Bowdoin College (Brunswick, ME: Bowdoin College Museum of Art, 1966), 164–66; Charles C. Calhoun, A Small College in Maine: Two Hundred Years of Bowdoin (Brunswick, ME: Bowdoin College, 1993), 53, 111–12.

44 Advertisements, Eastern Argus, October 6, 1818; Eastern Argus, December 8, 1818. Unfortunately, Pierce’s copies have not been identified.

45 Stuart charged one hundred dollars for a 30-by-25-inch portrait. See Carrie Rebora Barratt and Ellen G. Miles, Gilbert Stuart (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004), 204.

46 Joseph C. Anderson, comp., “Portland, Maine, Marriage Intentions, 1814–1837,” Maine Genealogist 30, no. 1 (February 2008): 36; Sprague, “Rufus Porter: A Life in Motion,” 21.

47 Deborah M. Child, “Thank Goodness for Granny Notes: Rufus Porter and His New England Sitters,” Antiques and Fine Arts 10, no. 4 (Summer/Autumn 2010): 190–95.

48 Gardner W. Pearson, comp., Records of the Massachusetts Volunteer Militia Called Out by the Governor of Massachusetts to Suppress a Threatened Invasion During the War of 1812 (Boston: Wright and Potter, 1913), 175; Sprague, “Rufus Porter: A Life in Motion,” 49n48. Other Porter-attributed portraits with related details have been found in a private collection, but unfortunately their sitters are not identified.

49 Sprague, “Rufus Porter: A Life in Motion,” 22–23; Alfred Cole and Charles F. Whitman, History of Buckfield, Oxford County, Maine (Lewiston, ME: Journal Printshop, 1915), 619. Unfortunately, Thomas’s miniature was cut down later for a smaller frame. For examples of the brush testing, see Child, “Rufus Porter’s Miniature Portraits,” 67–69.

50 Sprague, “Rufus Porter: A Life in Motion,” 12, 23.

51 Portland Gazette, July 7, 1818; Hallowell (ME) Gazette, July 29, 1818.

52 Sprague, “Rufus Porter: A Life in Motion,” 23. Porter’s first known advertisement for miniature painting appeared in the Middlesex Gazette (Concord, MA), February 5, 1820. He charged two dollars for likenesses that took ten minutes to complete. It is reproduced in Child, “Rufus Porter’s Miniature Portraits,” 69.