Thomas Earl Part II:

Who Was Thomas Earl?

Editor’s Note

Many of the basic biographical details presented by antiques dealers regarding the life and work of Thomas Earl proved to be based on hearsay and mistaken identity. The pieces just did not fit together. Deborah M. Child discovered a second Thomas Earl, a man who actually was a documented New Jersey schoolmaster, and she dauntlessly followed the historical record to conclude that this man was an Englishman who came to America as an indentured servant and reinvented himself.

Identifying the schoolmaster and artist who created the Thomas Earl copybooks has proved challenging. Gravestones and newspapers have provided little help (Fig. 1). The search has been further compounded by the dearth of early records for the colony of New Jersey. Named after the Isle of Jersey in the English Channel, it was not established as a Royal Province until 1664, when it was placed under the governorship of New York, which did not keep vital records prior to 1738. If not for church, probate, and land records, little could be gleaned about anyone residing in this colony in those early years.

In addition, the two public notices of Earl’s work proved to be full of statements that did not hold up to careful scrutiny of the historical record. A 1986 advertisement in The Magazine Antiques for Earl’s 1740–41 copybook identified the artist as having been born in Little Compton, Rhode Island, on January 17, 1704, and further notes that “Family tradition maintained he was a descendant of Ralph Earle, one of the founders of Providence [actually Portsmouth], Rhode Island, and a relative of the New England portrait painters Ralph Earl and his son R. E. W. Earl. In the 1720s, he had moved to Western New Jersey and died in New Hanover, Burlington Township, on November 2, 1751.”1

In a 2010 advertisement for the “Thomas Earl Copy Book” in Antiques and Fine Art, the identification of the schoolmaster as Thomas Earl, born in Rhode Island, was further expanded. “Thomas Earl was listed in a register of freeholders as ‘School Master’ and was a highly specialized ‘writing master,’ traveling from place to place, conducting classes at the local elementary schools and classical academies. Although he found students scattered within New Jersey, by far the most profitable region for practicing his profession must have been over the border of Pennsylvania.”2 No sources were cited for any of this intriguing but largely speculative information.

While there is a Thomas Earl whose birth is recorded in the Rhode Island vital records in 1703 or 1704, he was not the Thomas Earl who died in New Hanover in 1751.3 In his will, dated August 31, 1775, and proved on January 3, 1778, this Rhode Island-born Thomas Earl is cited as a yeoman with a plantation in New Hanover. In addition to making bequests to his children, he stated he was “heir-at-law to a valuable estate in New England, by my grandfather William Earl, which lies about fifteen miles from Rhoad [sic] Island.4”

Nor are there any references to this Thomas Earl serving as a schoolmaster. On November 6, 1727, he married Marcy Crispin (1705–1778) in a Quaker ceremony in Burlington, New Jersey.5 On the 1774 New Hanover tax list, this Thomas Earl is listed as owning 150 acres of land in New Hanover.6 The couple had six children, including Tanton (born c. 1731) and another son called Thomas (c. 1745/46–1811). In the 1779 tax lists for New Hanover, Tanton is cited as the owner of forty acres of land given to him by his father, while Thomas Earl, Jr. had inherited his father’s 150 acres.7

To further complicate matters, some descendants of the Rhode Island-born Thomas Earl erroneously claimed descent from Thomas Earl the schoolmaster. This idea was undoubtedly perpetuated by family historian Geneva Mattis Earl Schafer (d. 1994), who also maintained that the latter was the father of a Thomas Earl who died in Cumberland County in 1811.8

Much of the confusion comes from the fact that, in addition to the Rhode Island-born Thomas Earl, a second person by that name appears on the 1739 election returns for Burlington County. The latter is listed twice as a schoolmaster in New Jersey records—in a 1745 listing of freeholders (landowners entitled to vote) for the Township of New Hanover and in a 1751 inventory of his estate—convincing evidence that he was the creator of the copybooks.9

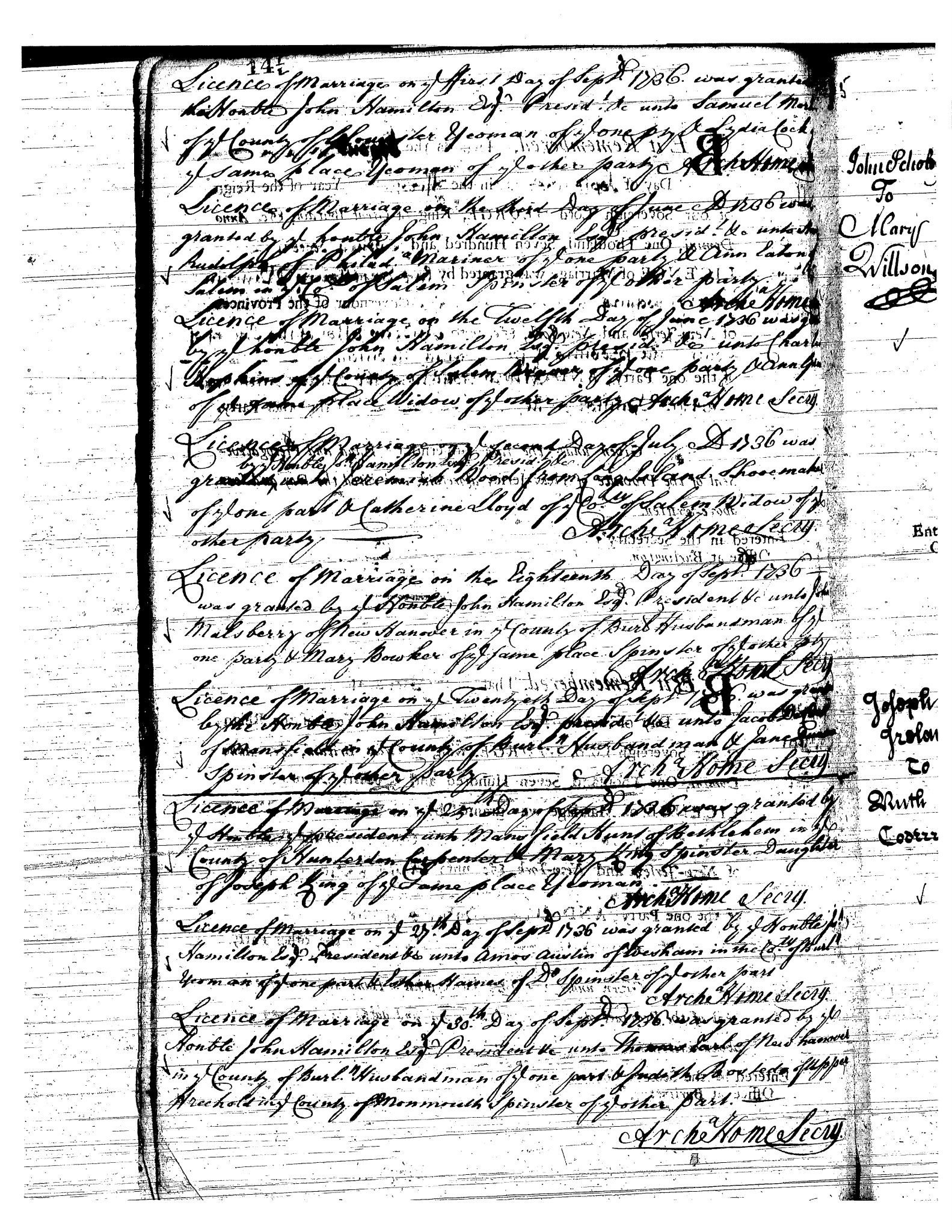

An important fact distinguishing this Thomas Earl from the other is that the schoolmaster was not a Quaker. His marriage bond, which is not from a Quaker meeting, is evidence of this: “On the 30th Day of September 1736 a license of marriage was granted by the Honorable John Hamilton Esq. President unto Thomas Earl of New Hanover in County of Burlington Husbandman of one part and Judith Bostedo of Upper Freehold in County of Monmouth spinster of other part.”10 How the two met is not known. Perhaps Earl had earlier spent some time teaching in Freehold. Judith (c. 1711–1793), whose surname is also spelled Bastedo and Bastido, was probably the daughter of tavern owner Joseph Bastedo, who was born on Staten Island, New York, in 1657, and his wife, Judith Ryke, also spelled Rycker, born in Port Richmond, Staten Island, in 1680. He was a surveyor and had a license to retail strong liquor before relocating his family to Freehold sometime before 1722 (Fig. 2).

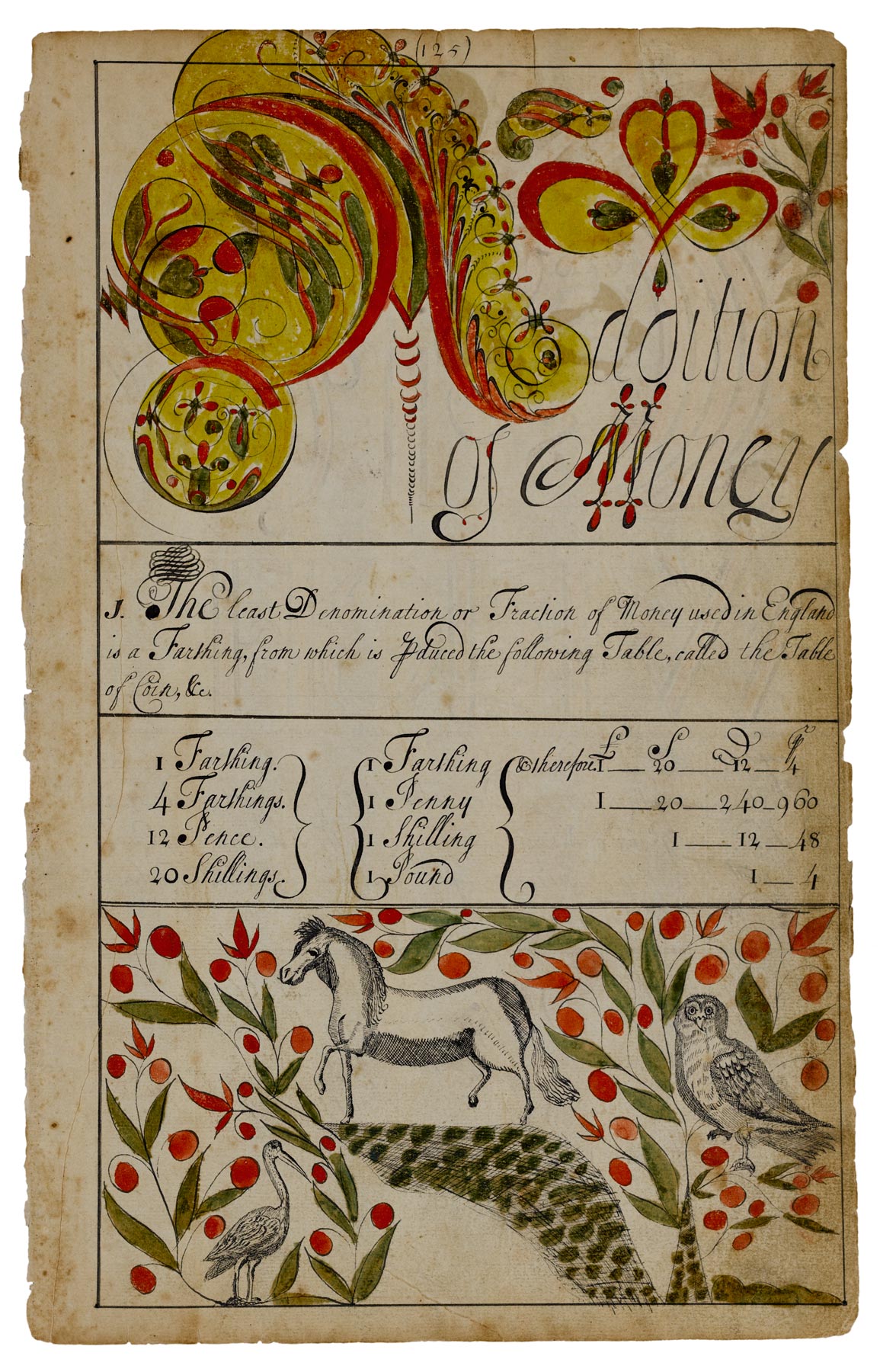

Why the couple chose to marry by license rather than banns is not known.11 Perhaps they had yet to establish a place of worship in New Hanover and did not want to wait. At the time of their marriage, Earl was described as a husbandman, suggesting he was either a free tenant farmer or a small landowner. Having his own plot of land, even a small one, meant he could provide sustenance for a family. With income from seasonal employment as a schoolteacher and other freelance work, the couple probably lived comfortably (Fig. 3).12

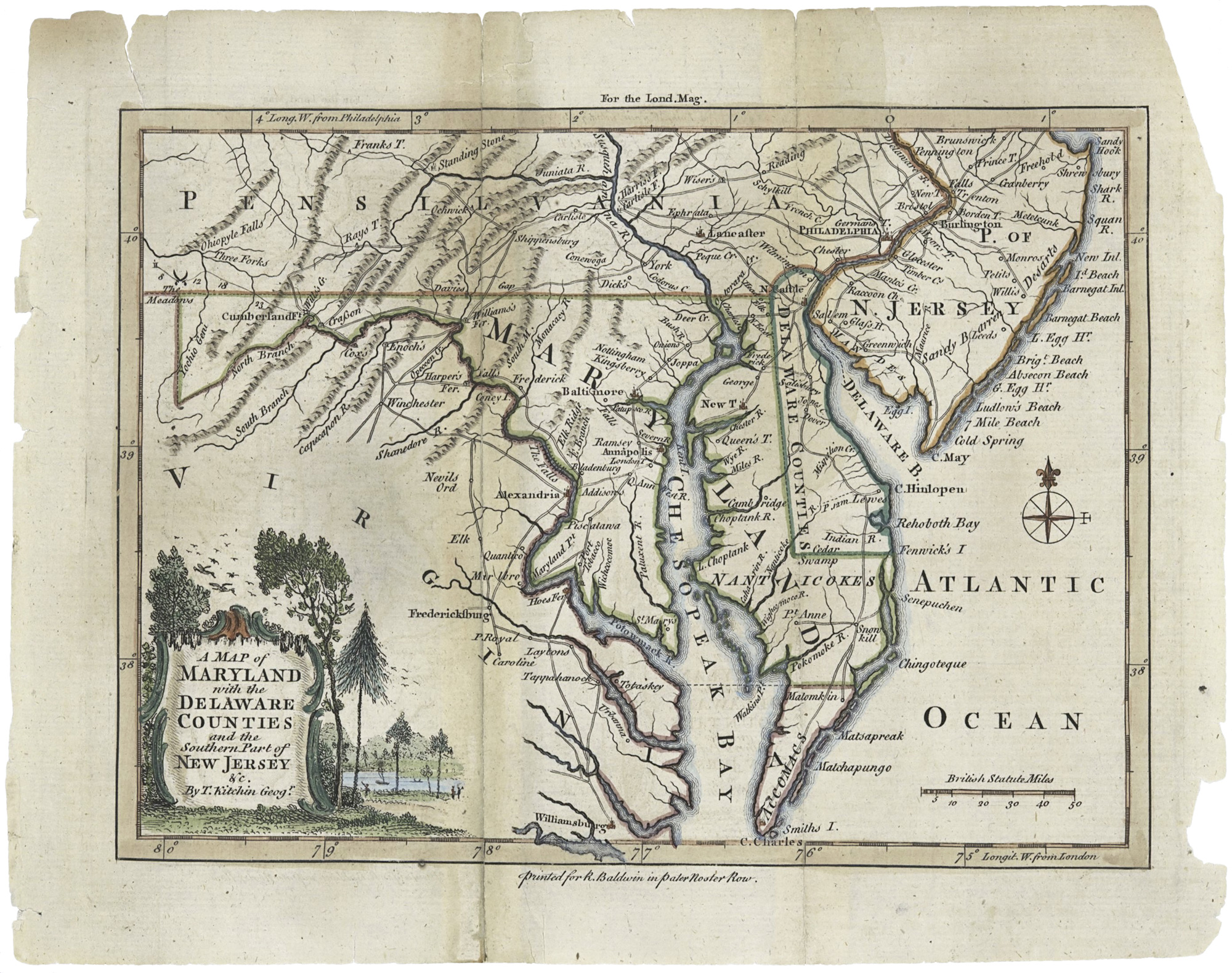

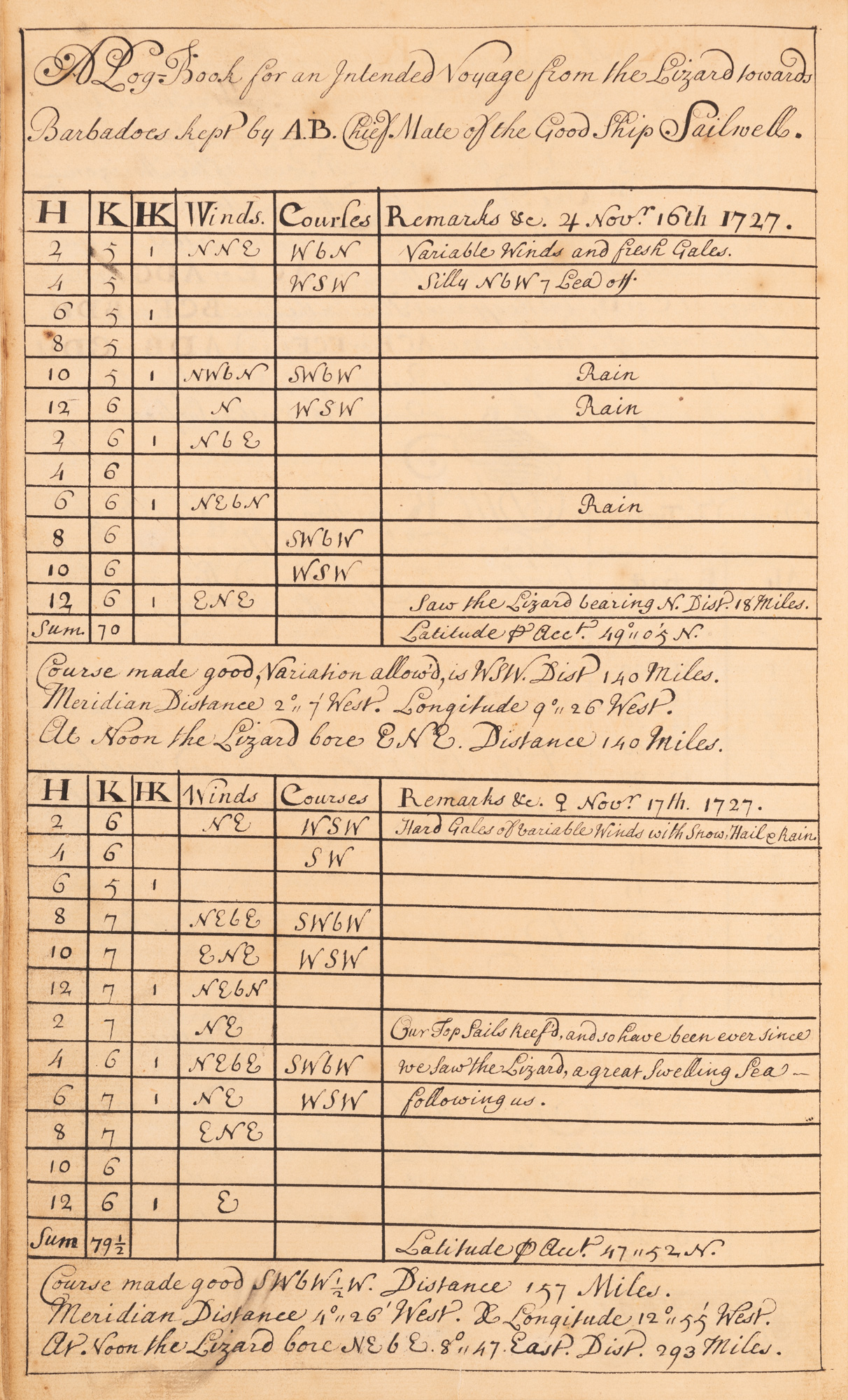

Unfortunately, there does not appear to be any record of where he might have been employed as a schoolmaster. Before the establishment of public schools, schools in the province were either privately run or operated under the patronage of a religious denomination. As Quakers placed tremendous emphasis on education and literacy in particular, they may well have been the first to engage Earl’s services as a teacher. In order to meet the educational needs of their network, which reached across towns, counties, and colonies all along the Delaware River, Earl probably traveled far and wide (Fig. 4).

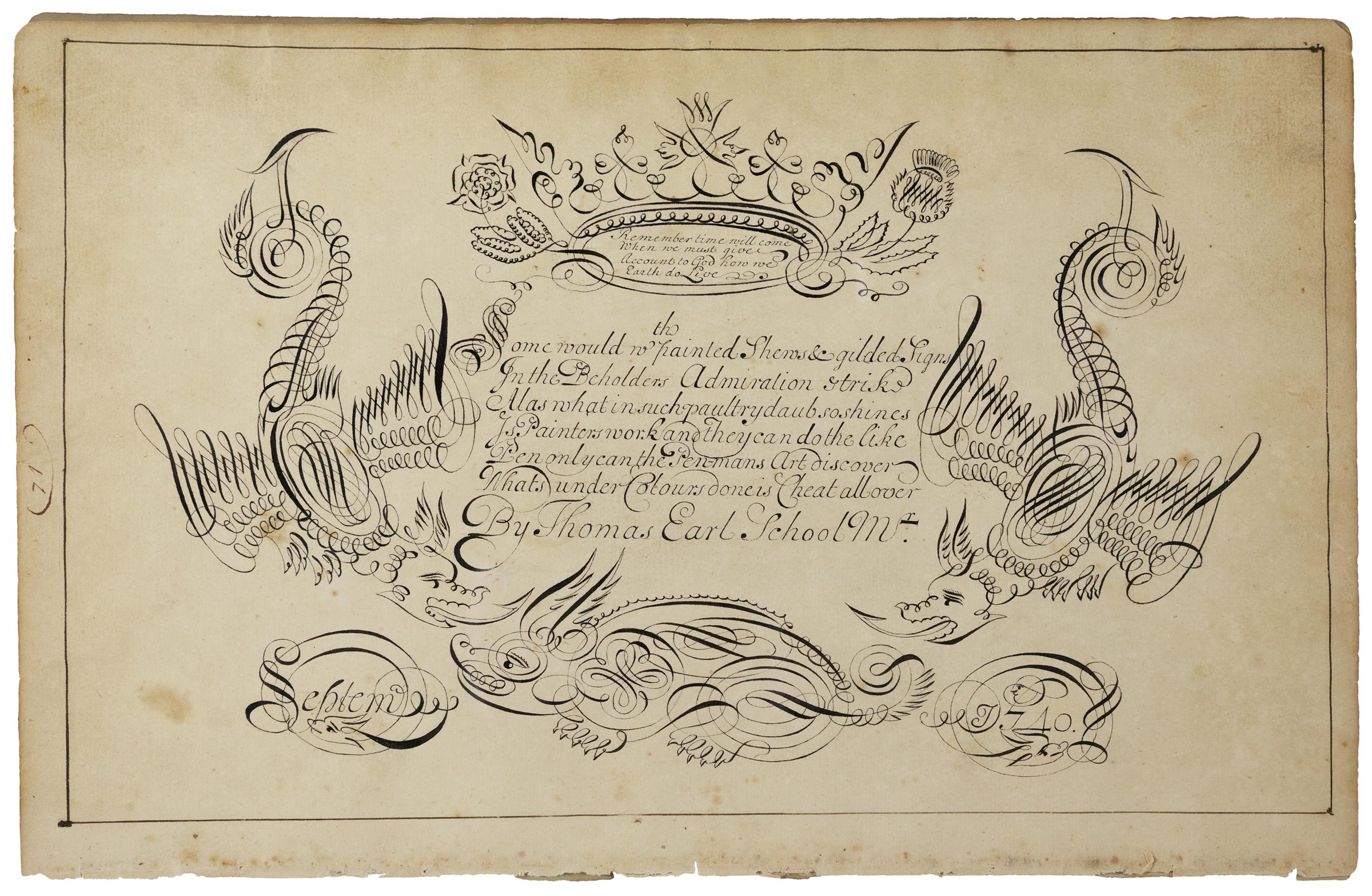

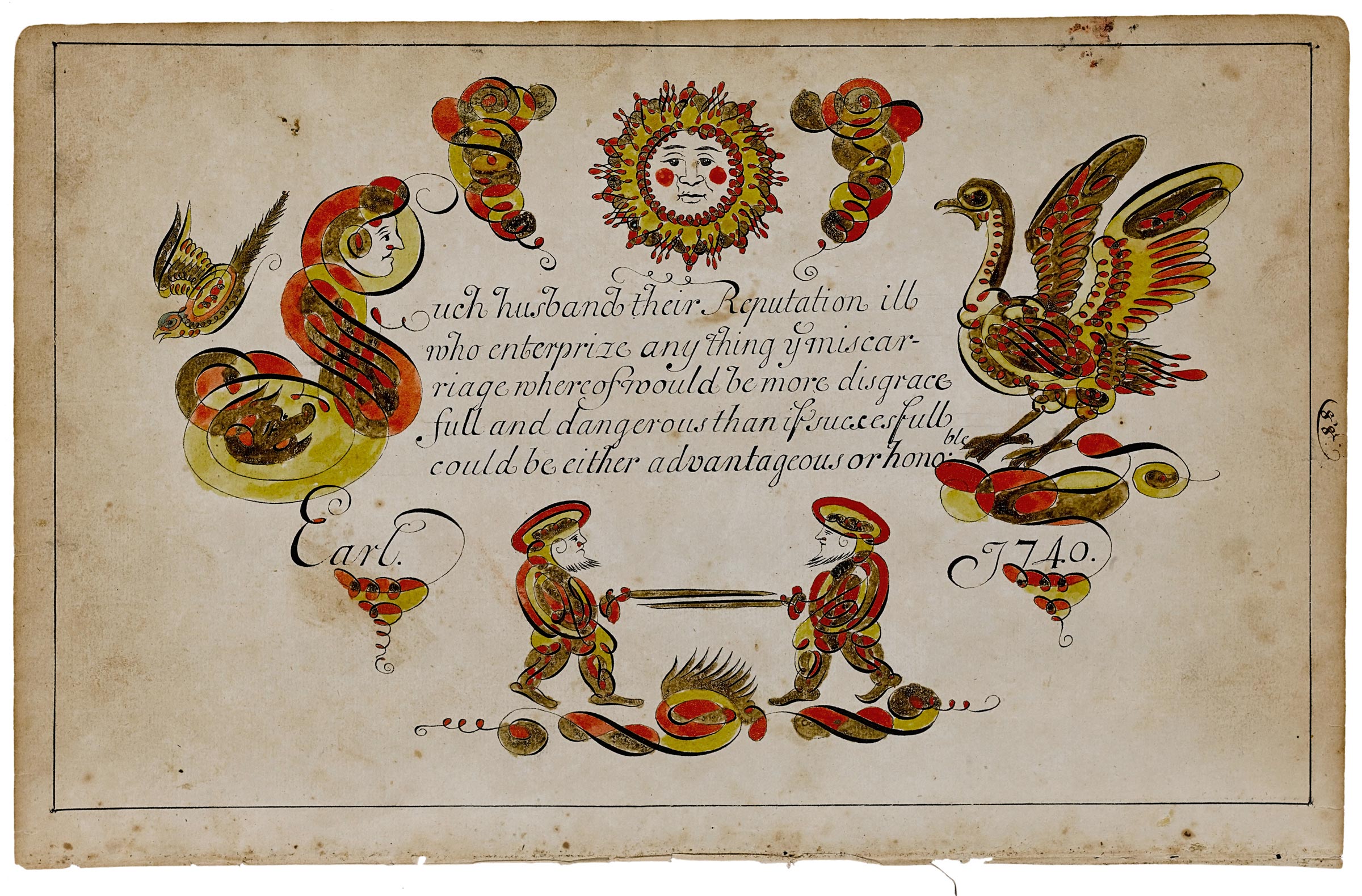

In September of 1740, Earl began assembling his lessons to create a single copybook that he carefully numbered up to page 910. At the time, he was probably away teaching and, not being burdened with chores at home, felt inspired to perfect his lesson book for his students. Given the high-quality King George paper he used, his stipend for teaching may well have included paper, which he often signed and dated (Figs. 5, 6).

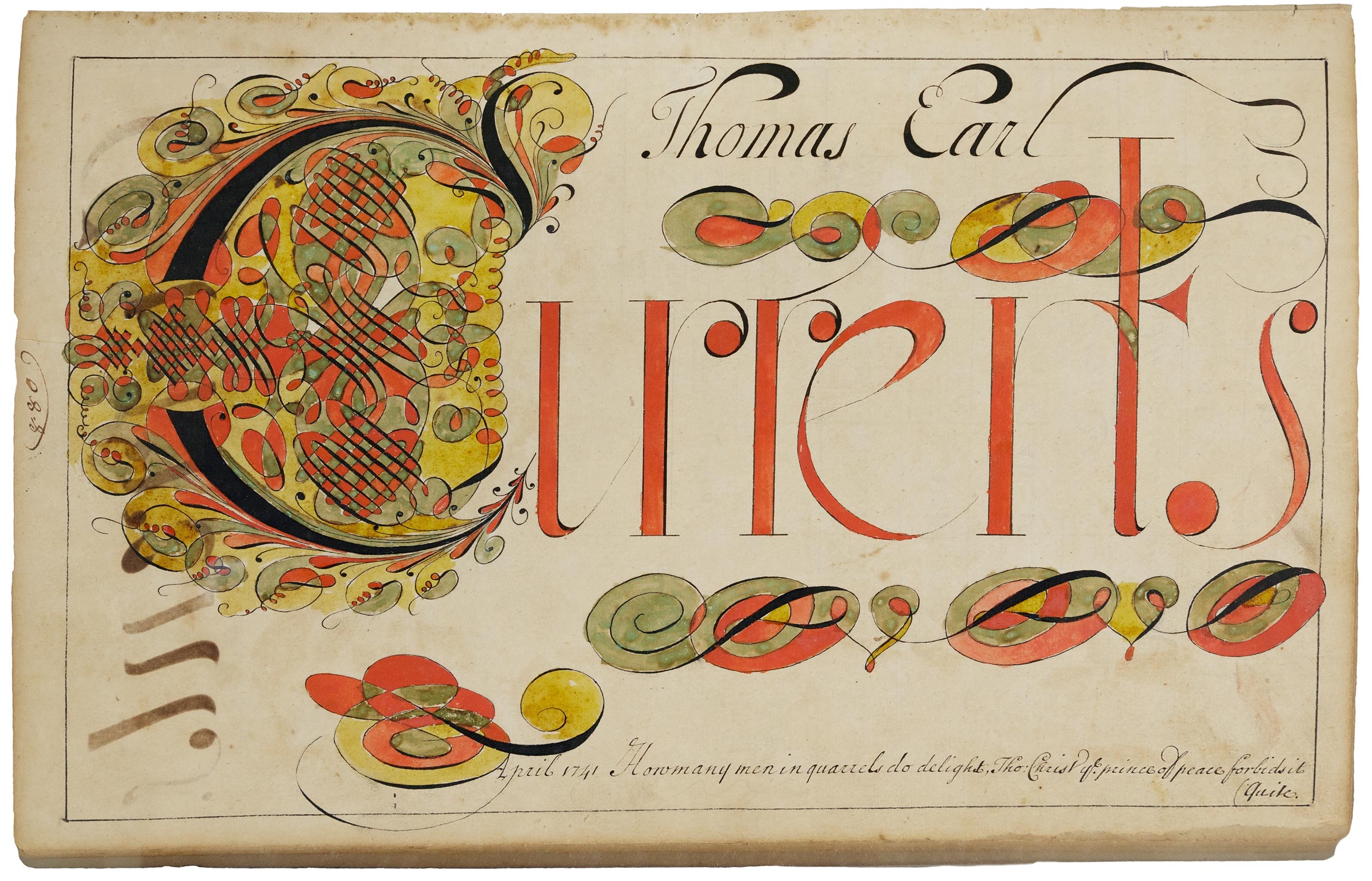

That the pages of the copybook were not arranged in the order that he created them in is confirmed by the fact that both page 565 and page 880 are inscribed “Thomas Earl April 1741.” After that year’s term ended, Earl probably returned home to plant crops and to wait for the arrival of his son John, who was born shortly thereafter (Figs. 7, 8).13

As the latest addition to his copybook, page 781, is dated December 10, 1741, he was probably by then teaching full-time in his own neighborhood. This would explain why he is cited as the schoolmaster on the 1745 listing of freeholders for New Hanover.

On October 4, 1751, Earl died intestate (without a will) in New Hanover. On November 2, an inventory of his “money, goods, and chattels [personal property]” was conducted by his neighbors John Steward and John Bullock. In addition to a horse and colt, three cows, two hogs, and a plow, his estate inventory included “the new room with bed, looking glass and table, desk, the parlor with bed furniture and other things, the chamber with bed, the study with books, kitchen with pots and pans and cellor [sic] with cider tubs.” As the inventory suggests, Earl was a man of extremely modest means; his estate was valued at just over £181. His most valuable possessions were his purse and clothing, valued at twenty-one pounds, and the books and other items contained in his study, valued at eighteen pounds.14

On January 2, 1752, local landowners Thomas Emley (who owned 270 acres), Joseph Steward (210 acres), Abraham Brown (170 acres), along with Samuel Woodward, esquire of Crosswicks and the local magistrate, posted a bond of five hundred pounds so his widow “Judeth [sic] Earl” could settle his estate.15

Two years later, Judith married Quaker widower Joseph Norcross (1725–1766). He was a shopkeeper in Hampton, Hanover Township, in Burlington County. Judith served as executor for his estate in 1766.16 She reportedly died in New Hanover in 1793.

But where did her Earl hail from? The first clue to his origins is found in Pliny Earle’s The Earle Family, Ralph Earle and His Descendants, published in 1888. The book mentions a Thomas Earl, “who arrived from England and settled in Burlington, New Jersey or its vicinity sometime between 1720 and 1740. Earl had a son John and a grandson named Samuel W. Earl who was still living in Burlington in 1878 [he actually died in 1875] and had another son Gibtersharp [or Gibterthorpe] who died in Ohio in 1850 [or 1851].”17

In 1791, John moved from New Hanover to Burlington, where he kept a tavern, as had his maternal grandfather, Joseph Bastedo, in Staten Island. In his will, dated February 5, 1805, he names his second wife, Hannah, and sons Gilberthorp, William Norcross (probably named in honor of his stepfather Joseph Norcross), and Samuel Woodward (named for his father’s estate administrator).18 Someone from this family had clearly been in communication with Pliny Earle before his book’s 1888 publication to inform him of their circumstances and that their patriarch’s place of birth was England. However, they were too many generations removed to know exactly when he had arrived, other than to know it was before the birth of his son John in 1741.

Assuming this lineage is accurate, this man may well have been the Thomas Earl born about 1712 in Kingston upon Thames, Surrey, twelve miles west from central London. He was the son of joiner John Earle and Elizabeth Hind and the grandson of Thomas Earl, a waterman licensed to navigate boats on the Thames.19 On July 30, 1713, Thomas was christened in the church of St. Saviour in Southwark, now known as Southwark Cathedral.20

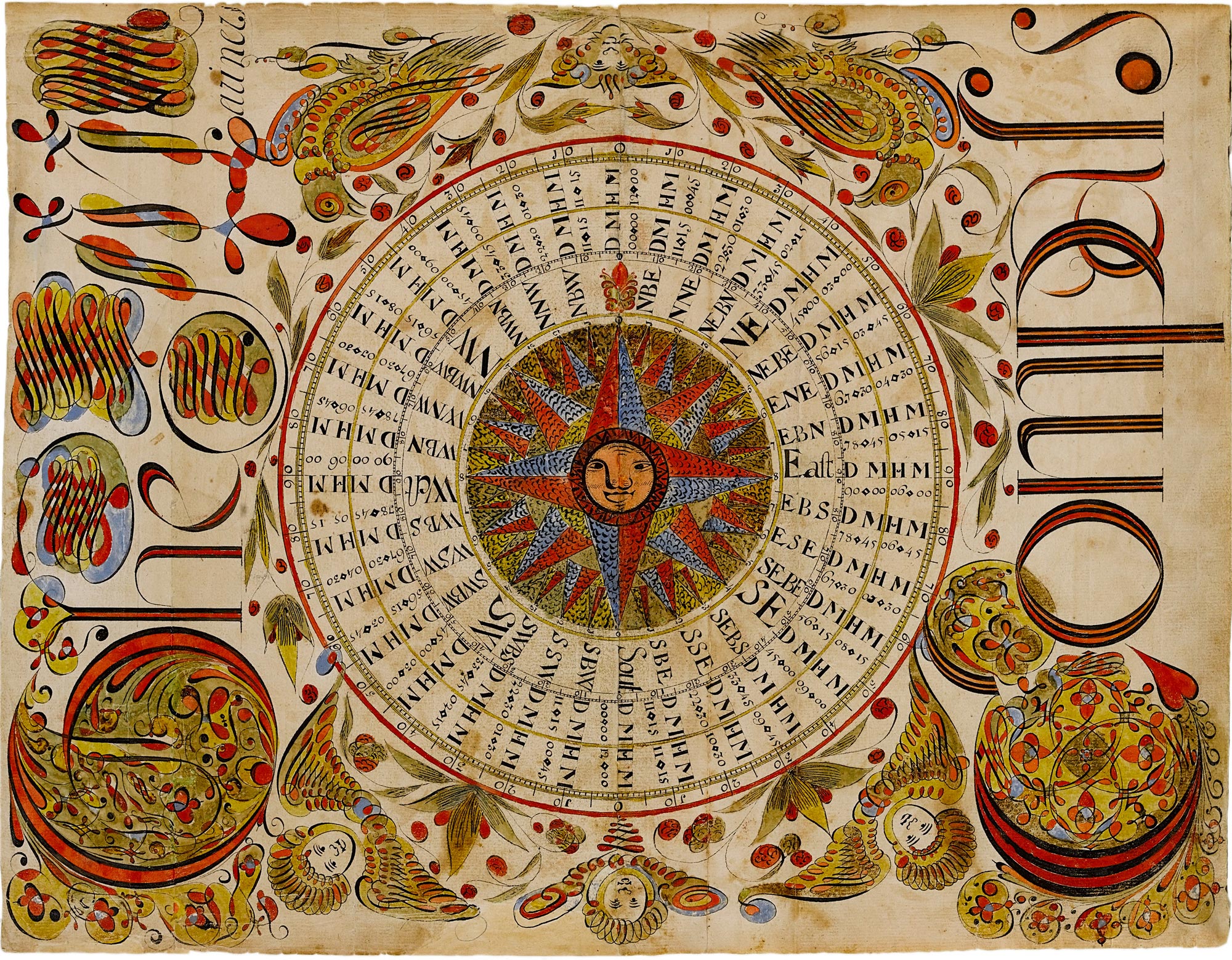

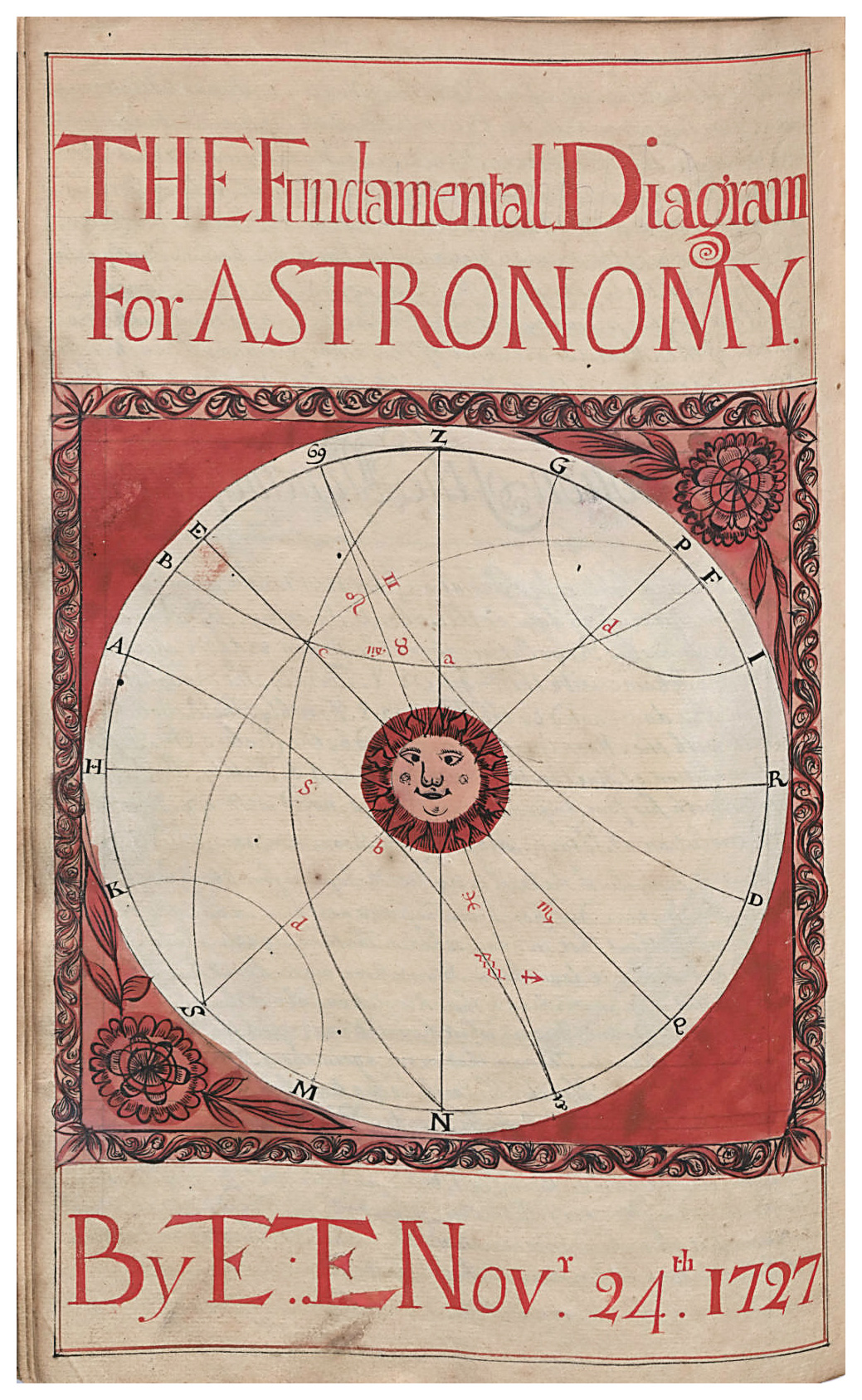

He probably attended a parish or local school, where he may well have created the copybook now in the collection of the Winterthur Library. In contrast to the 1740 sheet inscribed “Thomas Earl, Schoolmaster” (Fig. 5), the cover of his earlier copybook is simply inscribed “TE’s book,” as befitting a student. One folio sheet, “The Fundamental Diagram for Astronomy,” is signed “TE” and dated November 24, 1727 (Fig. 9). Other dates that appear in the book are March 19, 1726, February 1, 1727, August 15, 1727, and November 11–27, 1727.

Earl would have been at least fifteen years old when the book was created and living in a place where navigational and astronomical instruction would have been emphasized. As described earlier, this copybook consists of 176 pages on paper watermarked King George II and draws heavily on published English teaching manuals of its time. It is executed in a limited palette. Earl’s relative youth would also be consistent with the simpler lessons and more restrained embellishments contained within its pages (Fig. 10).

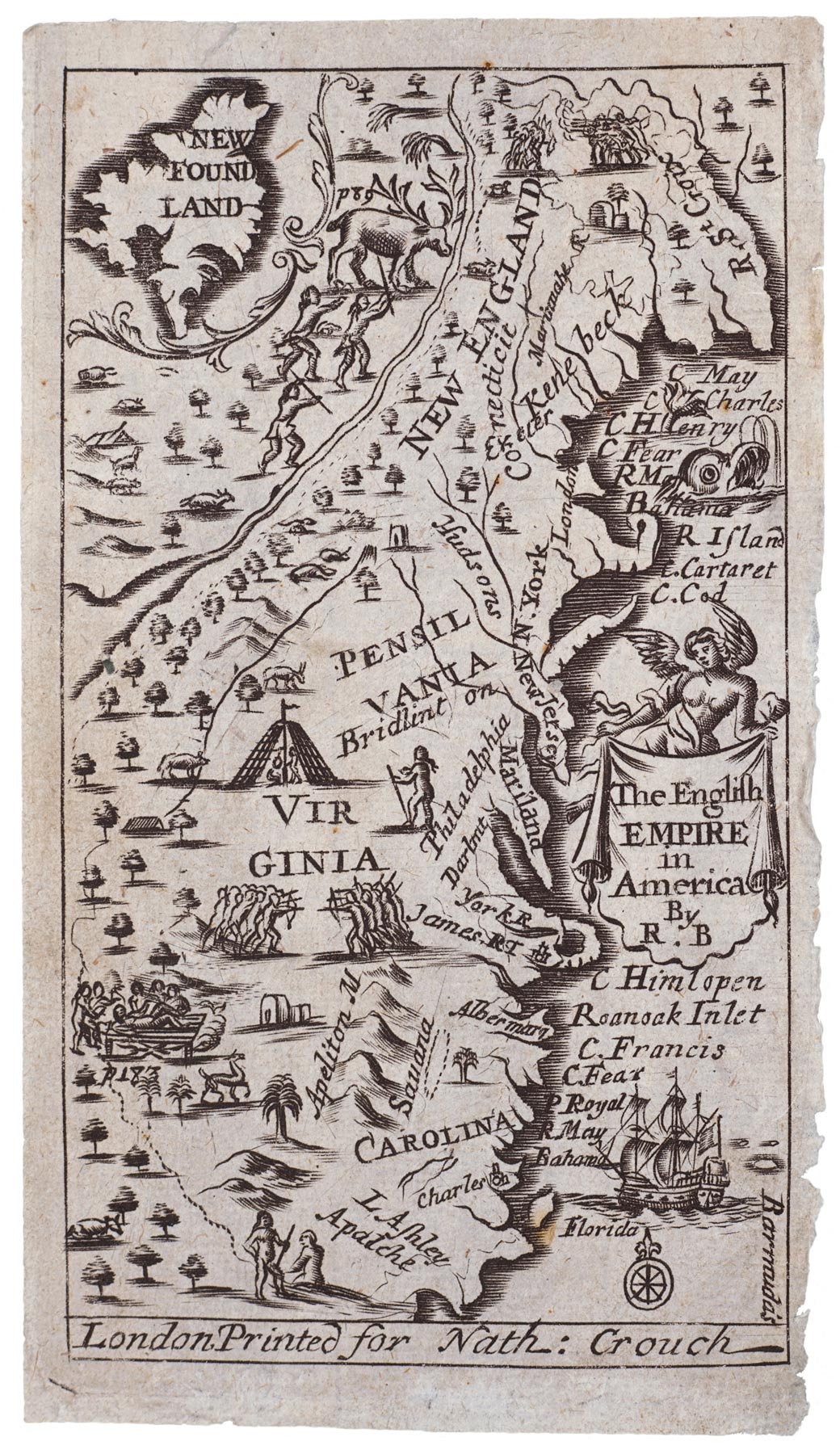

On June 21, 1731, at the age of nineteen, Earl signed indenture papers committing to four years of service as a gardener in the colonies, probably in exchange for his passage to Philadelphia. This may have been prompted by worsening economic conditions in Britain.21 As his 1727 map of the “English Empire” (Fig. 11) is based on Nathaniel Crouch’s 1685 map (Fig. 12), one wonders how much knowledge he actually had of his destination.

The agent who had arranged for his contract was named Peter Simpson. He was a London victualler who was probably supplying provisions for the ship on which Earl was to sail. As the agent responsible for at least seventeen indentures on the voyage, he was no doubt making a healthy profit by helping to fill the boat to full capacity.22

Indentured servitude played a central role in the peopling of the American colonies. Between one-half and two-thirds of all people who went to the colonies south of New England were servants.23 Like many British immigrants who arrived as indentured servants, Earl may have signed on with a vision of earning better wages and buying his own plot of land. However, for many of the indentured, the reality was quite different. Sadly, more than a few found the only way to escape from those who purchased their indenture was to run away, as Earl’s fellow passenger Daniel Mills did.24

Why Earl, who was educated, listed his occupation as gardener is not hard to understand. As early American families worked to establish their homes and plantations, gardeners were much more in demand than teachers. Philadelphia was the largest and most rapidly growing city in the colonies. Fortunes were made from the iron furnaces and forges along the upper Schuylkill River, and increasingly well-to-do families were able to employ retinues of servants.

Unlike teaching, which provided notoriously poor pay and low social status, gardening was considered a worthy occupation, replete with intellectual challenges.25 Propagating plants and maximizing crop yields required concentration and attention to detail. Gardening manuals and journals were being written by professionals within the trade, who included market gardeners, nursery men, botanists, and florists.26 Knowledge gleaned in its practice would be useful for anyone immigrating to Pennsylvania with ambitions to become a landowner.

Many gardeners had knowledge of herbs and their medicinal applications and also knew how to select botanical pigments and wash, grind, and mix them for watercolor painting. That Earl was working as a gardener would certainly explain how he came to have access to choice organic materials when making his own colors and why he could apply them so richly. As gardening was also a largely seasonal trade, this line of work would have allowed time for him to pursue further studies and experiment more as an artist (Fig. 13).

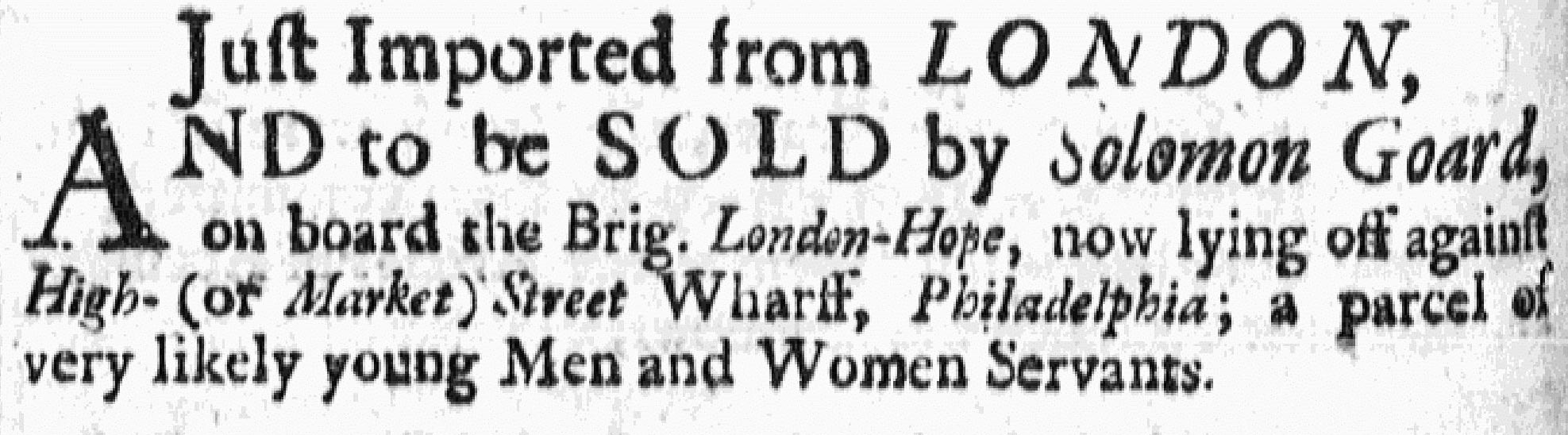

Earl would have sailed on the London-Hope, the same ship that Benjamin Franklin had sailed to London on in 1724. Captained by John Howell, it departed from London on July 26, 1731, and arrived in Philadelphia on September 30.27 On arrival, Earl’s specialized skills would have appealed to a range of people seeking such services. This was not necessarily a timely business; auctioneer Solomon Goard was still advertising “a parcel of very likely young Men and Women servants” right up until the London-Hope’s departure on November 4 (Figs. 14, 15).28

Although it is not known who procured Earl’s services, given the scope of lessons in his later copybook, it would appear that he stayed in the vicinity of Philadelphia, where there was a major emphasis on self-betterment. In 1731, publisher Benjamin Franklin founded the Library Company of Philadelphia, which was America’s first lending library. From the 1730s onwards, a number of teachers in Philadelphia were giving lessons in the advanced subject matter that Earl chose to include in his copybook.29

Lessons could also be had at the Free School in Strawberry Lane, established by the Quakers as early as 1728.30 As his copybook compares so well to the quality of penmanship, calligraphy, art work, and mathematics demonstrated by pupils at Royal Mathematical School within Christ’s Hospital in London, Earl may well have begun his later copybook after being inspired by seeing a manuscript by someone who had attended that esteemed school.31

That Earl came here as an indentured servant would also explain why the family’s knowledge of his time of arrival—sometime between 1720 and 1740—was so vague. Having to stand on the deck of a boat as bids were placed for one’s labor may not have been an experience Earl chose to share with his wife and child.

Although it cannot be proved definitively that it was the Thomas Earl who arrived from London in 1731 who created the two copybooks, the modest holdings of Thomas Earl the schoolmaster’s 1751 estate, whose wife simply signed his estate papers with her mark, are consistent with someone who first arrived in this country as an indentured servant. Given his premature death and his widow’s subsequent remarriage, it is not surprising that details concerning who created these two copybooks would have been garbled and their history of ownership remains unknown.

Regardless of his incredible artistic talents and devotion to his profession, Earl clearly led a marginal existence. There is not even a record of where he is buried.

Acknowledgments

About the Author

1 The term “Rhode Island” at that time meant the Island of Aquidneck on which Portsmouth and Newport are located, and did not include Providence. Jane Fiske, email correspondence to author, March 26, 2021.

2 Advertisement for the Thomas Earl copybook, Antiques and Fine Art, Spring 2010, 68–69.

3 Thomas Earl birth records, Rhode Island Vital Extracts, 1636–1899, 21 vols., comp. James Newell Arnold (Providence, RI: Narragansett Historical Publishing Company, 1891–1912), accessed via Ancestry.com. Earl’s parents are listed as William Earl (1672–1715) and Hebzebath Butts (1673–1722), and his grandfather as William Earl (1634–1715).

The author has not been able to find any documentation that Thomas was his grandfather’s heir-at-law. The only legacy cited in William’s will, dated November 13, 1713, was a brass milk pan for Thomas’s father, William. Will and estate inventory kindly located for author by Mandy Lawson, town clerk, Portsmouth, RI. The author also thanks Letty Champion, Anne Northrup Burns, and Michael P. Dwyer for aiding in earlier queries.

4 Thomas Earl, will dated August 31, 1775, proved January 3, 1778, in New Jersey Abstracts of Wills, 1670–1817, vol. 34 (Trenton, NJ: John L. Murphy Publishing), 156–57, accessed via Ancestry.com.

Many of the Earles settled in Dartmouth, just across the Sekonnet River in Massachusetts, which fits the “15 miles from RI” description. Jane Fiske, email correspondence to author, March 26, 2021.

5 Minutes of Society of Friends meeting, Burlington, New Jersey, November 6, 1727, Quaker Meeting Records, Friends Historical Library, Swarthmore College, Swarthmore, PA, accessed via Ancestry.com.

6 Tax lists, New Hanover, New Jersey, September 1774, book 259, box 13, County Tax Ratables, 1921.001, New Jersey State Archives, Trenton, accessed via Ancestry.com (hereafter cited as Tax Ratables).

7 Tax lists, New Hanover, New Jersey, March 1779, book 260, box 13, Tax Ratables.

8 Schafer’s role in this was kindly brought to my attention by family historian Bonnie Hicks. Email correspondence to the author, October 4, 2020.

9 New Jersey Census and Census Substitutes Index, 1643–1890, accessed via Ancestry.com; Carlos E. Godfrey, comp., “A List of the Freeholders for the City and County of Burlington and in Each Respective Township taken this 15th Day of April 1745,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 29, no. 4 (1905): 421–26; Administration bond for the estate of Thomas Earl of New Hanover, January 2, 1752, Estate Records, New Jersey State Archives (hereafter cited as Estate Records).

A third Thomas Earl is listed on the 1745 freeholder’s list as a resident of Springfield, New Jersey. He had inherited land from his father, Thomas. On the tax records for Springfield for 1770 he is listed as owning about 280 acres, thirty cattle, and two slaves or servants. Tax lists, Springfield, September 1774, Tax Ratables, film 411291, family number 20. His last will and testament, dated 1807, refers to him as a resident of Springfield and names a deceased wife, Rebecca, sons Michael, Thomas, and Clayton, and daughters Susanna and Martha. Burlington County Surrogate’s Court, New Jersey Wills and Probate Records, 1739–1991, accessed via from Ancestry.com (hereafter cited as Burlington Surrogate’s Court).

In 1743, Thomas Lambert’s 1,459 acres of West Jersey land were surveyed and sold. Amongst the listings of sales are eight purchases of land by Thomas Earl. With three Thomas Earls residing in West Jersey at that time, it is not clear who purchased the land. Warrant of surveyor general by legatees of Thomas Lambert, August 4, 1743, Early Land Records, East and West Jersey Proprietors, New Jersey State Archives.

10 Thomas Earl and Judith Bastedo, marriage bond, September 30, 1736, Colonial Marriage Bonds, 1711–1795, New Jersey State Archives.

11 Banns of marriage, introduced by the Catholic Church in medieval Europe, were public legal notices, posted in a church, proclaiming intent to marry and thereby giving notice that anyone aware of an impediment should make their objection known. The practice was common but not statutory in colonial America.

12 For example, David Evans, advertising his services as a country schoolmaster, also offered to copy charts and maps. Pennsylvania Gazette (Philadelphia) June 8, 1738.

13 An Earl family tree posted by user maryevhill on Familysearch.org lists Thomas’s son John Earl’s birth as April 6, 1740. No documentation is cited. Other family trees on the site give his birthdate as May 8, 1741.

14 Thomas Earl, inventory of property, November 2, 1751, Estate Records. No land is cited in the inventory.

15 Administration bond for the estate of Thomas Earl, Estate Records.

16 Joseph Norcross, will dated May 2, 1766, New Jersey Abstract of Wills, vol. 33, 309–10. Their marriage is recorded as 1753.

17 Pliny Earle, The Earle Family, Ralph Earle and His Descendants (Worcester, MA: Charles Hamilton, 1888) xiii–xv. Samuel Woodward Earl’s will is dated July 1, 1875. He died seventeen days later. Burlington Surrogate’s Court.

18 John Earl, will dated February 5, 1805, Burlington Surrogate’s Court. Given the unusual name choice of Gilberthorp, it seems plausible the family may have had contact with Edmund Beakes and his wife Ann Gilberthorp. Edmund and his brother Stacy were both cabinetmakers in Burlington County.

19 Upon completion of his apprenticeship in 1712, Earl’s father became a member of the Joiners’ Company, a fraternal organization of woodworkers. John Earle, record of freedom from indenture, December 2, 1712, Joiners’ Company Records, MS 8052/5, f. 76, Guildhall Library, accessed via British and Irish Furniture Makers Online, Furniture History Society.

Grandfather Thomas was still active as a waterman as late as 1725, when an apprentice of his was drowned on the Thames. Daily Post (London), February 12, 1725.

20 His parents’ marriage is recorded in that same church. John Earle, marriage record, January 13, 1711, Church of England Baptisms, Marriages and Burials 1538–1812, Reference Number P92/SAV/3005, London Metropolitan Archives.

21 Marion Kaminkow, comp., A List of Emigrants from England to America, 1718–1759 (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing, 1989), accessed via Ancestry.com. Indentured servants coming from Kingston upon Thames, were rare. Out of 3,112 indenture records filed at Guildhall, London, transcribed by Kaminkow, only two others were from Kingston upon Thames: William Howard (age twenty, no occupation, destined for Maryland, four-year indenture beginning 1772) and John Windon (age twenty, destined for Maryland, five-year indenture beginning 1750).

22 Kaminkow, List of Emigrants from England.

23 John Wareing, Emigrants to America: Indentured Servants Recruited in London, 1718–1733 (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing, 1985), 8.

24 “Run away from George Aston,” Pennsylvania Gazette, September 18, 1746.

25 For one day making and carting hay on July 25, 1745, George Eyre was owed £3 6s. Yet for instructing the sons of Burlington physician Thomas Shaw in the theory of navigation from 1749 to 1750, he was paid a meager six pounds. Thomas Shaw v. George Eyre, New Jersey Supreme Court case no. 35017, August 7, 1751. In an advertisement in the Pennsylvania Gazette, September 11, 1746, Quaker John Emley was seeking to fill vacancies for two to three teachers for eighteen to twenty pounds a year with accommodations.

26 Ellen Butoescu, “Eighteenth-Century Garden Manuals: Old Practice, New Professions,” Romanian Journal of English Studies (December 2016): 69–77.

27 This was the first voyage captained by Howell. Daily Advertiser (London), July 28, 1731. The London-Hope regularly sailed between London and Philadelphia with occasional stops in the Caribbean. Crossing times varied. In 1727, the crossing from London to Philadelphia took 109 days, while in 1728 the ship crossed in fifty-seven.

28 “And to be sold by Solomon Goard” American Weekly Mercury (Philadelphia), September 30, 1731.

29 In the American Weekly Mercury, September 27, 1733, Andrew Lamb advertised his services as a “school master in Philadelphia,” and in a later advertisement, in the Pennsylvania Journal, March 21, 1749, stated he had over thirty years’ experience teaching. Theophilus Grew advertised “Reading, Writing, Vulgar” in the American Weekly Mercury, March 9, 1736.

30 American Weekly Mercury, November 28, 1728.

31 For an in-depth study of cyphering books at the Royal Mathematical School, see Nerida F. Ellerton and M. A. Clements, “From the Royal Mathematical School: Charles Page, 1825,” in Abraham Lincoln’s Cyphering Book and Ten Other Extraordinary Cyphering Books (London: Springer, 2014), 255–96.