Thomas Earl, Part III:

Artist Extraordinaire

Editor’s Note

Artist Extraordinaire

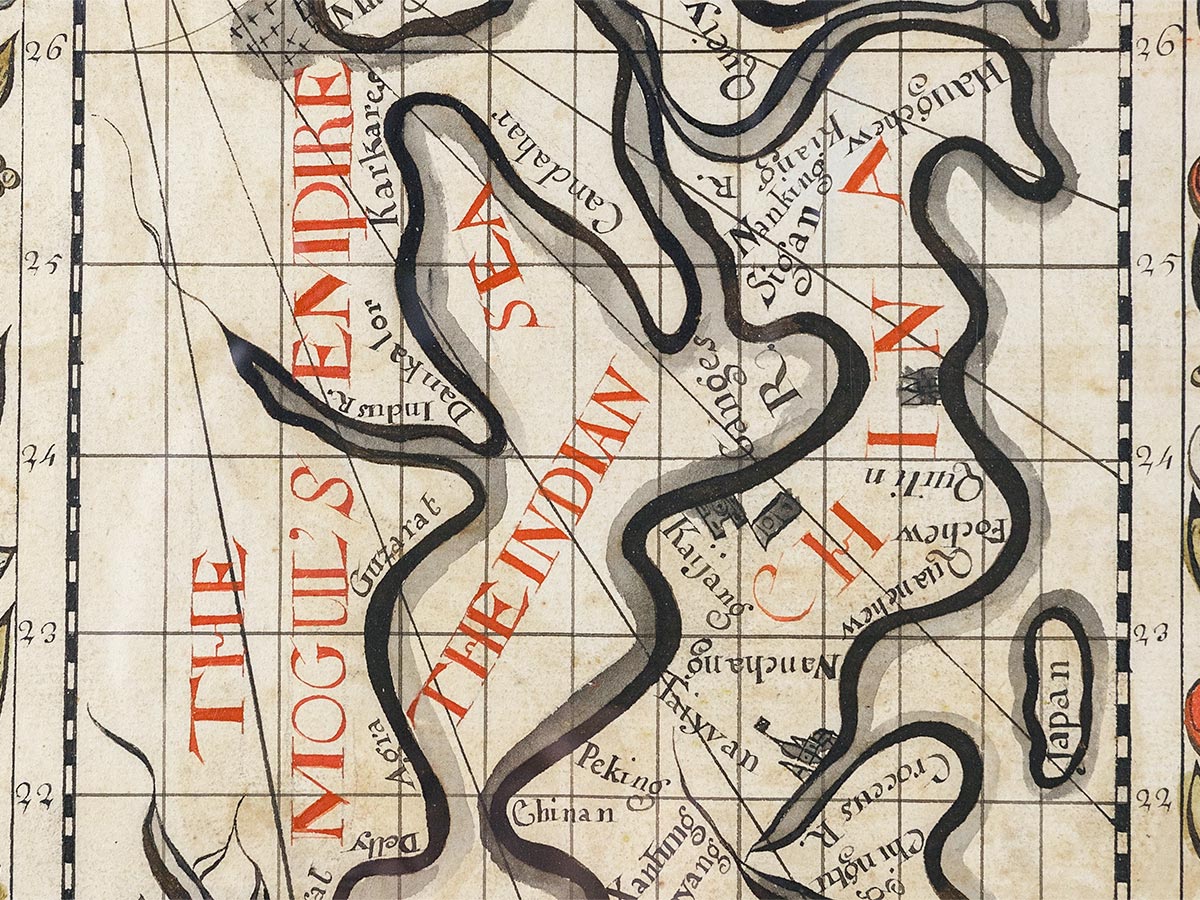

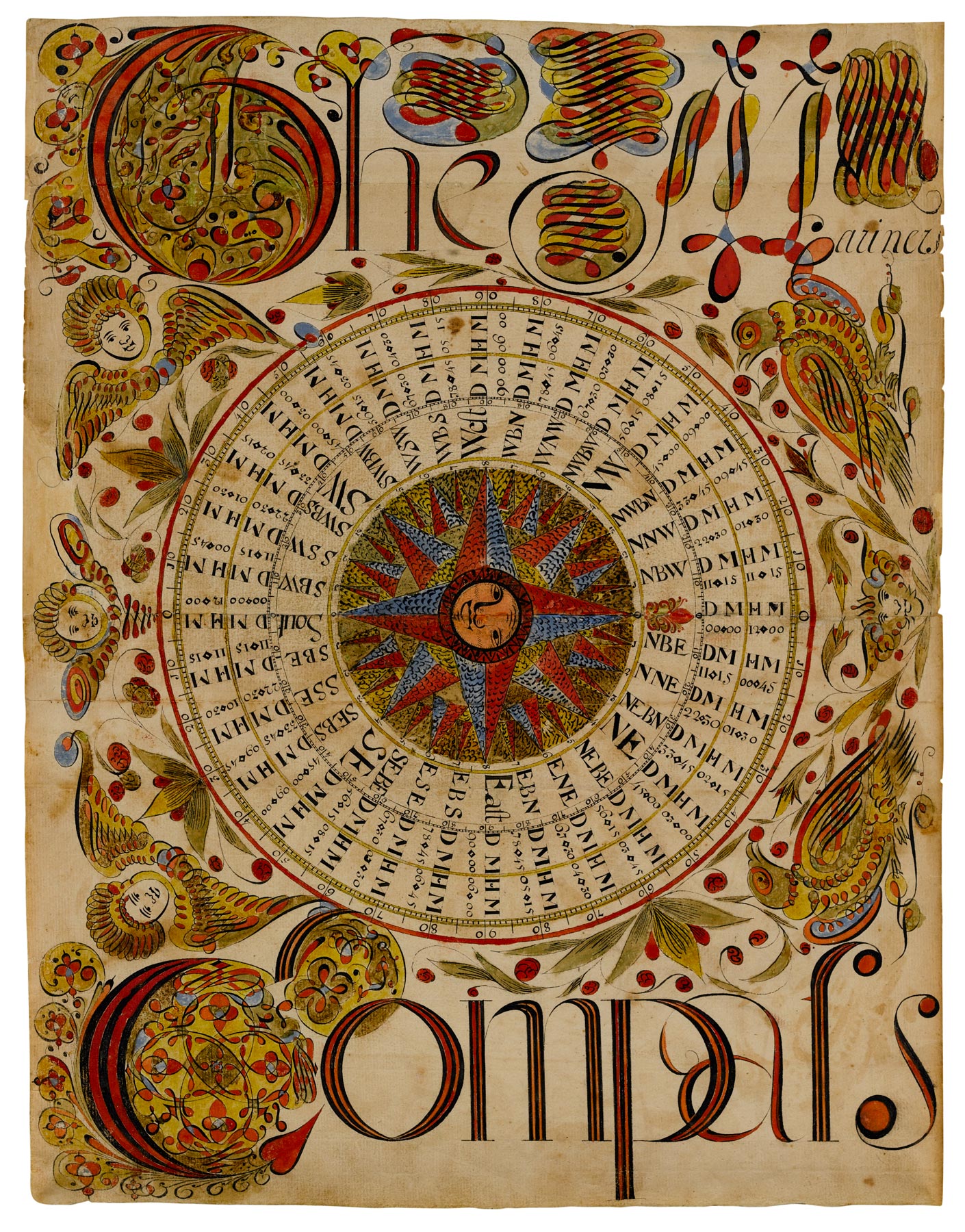

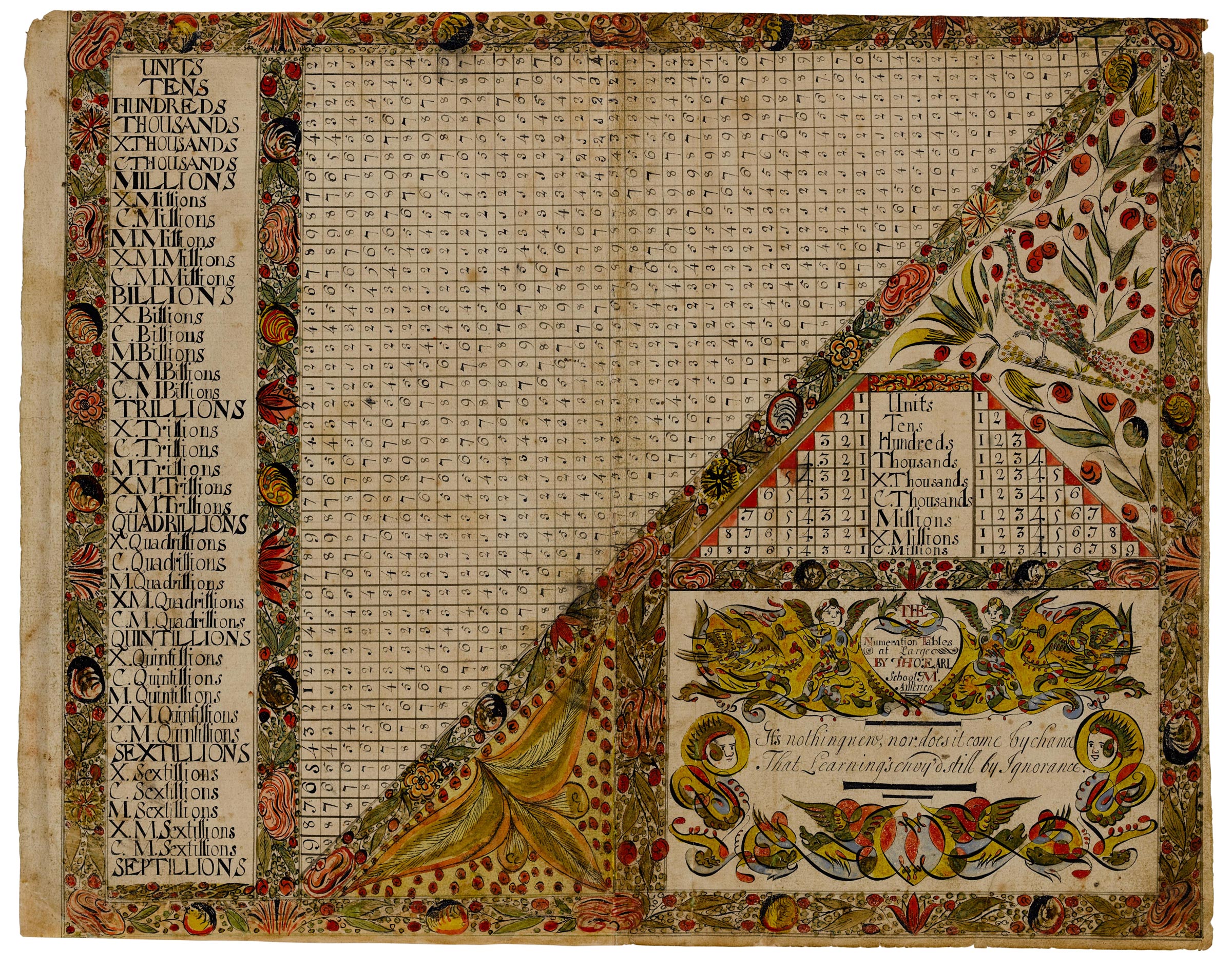

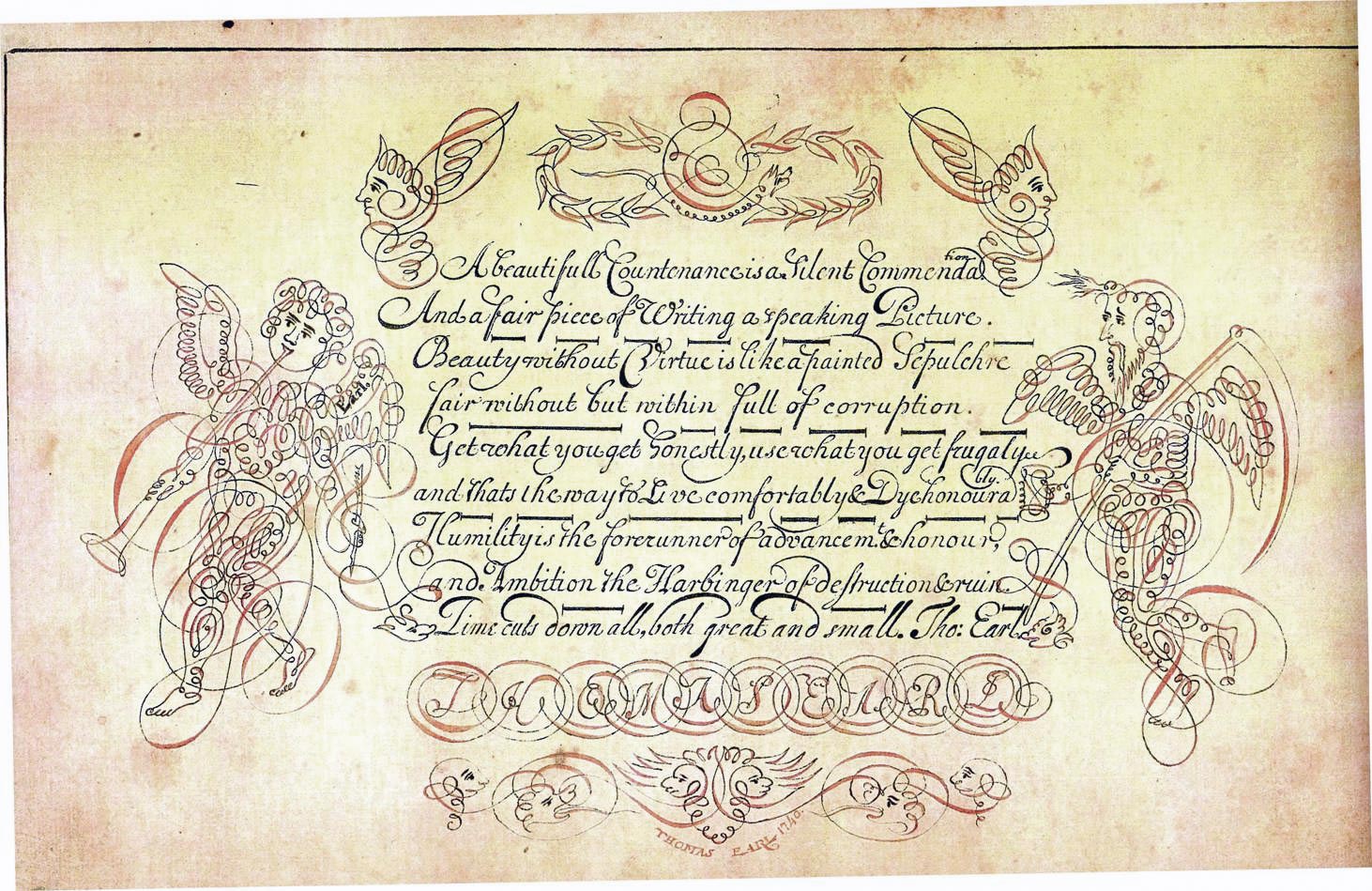

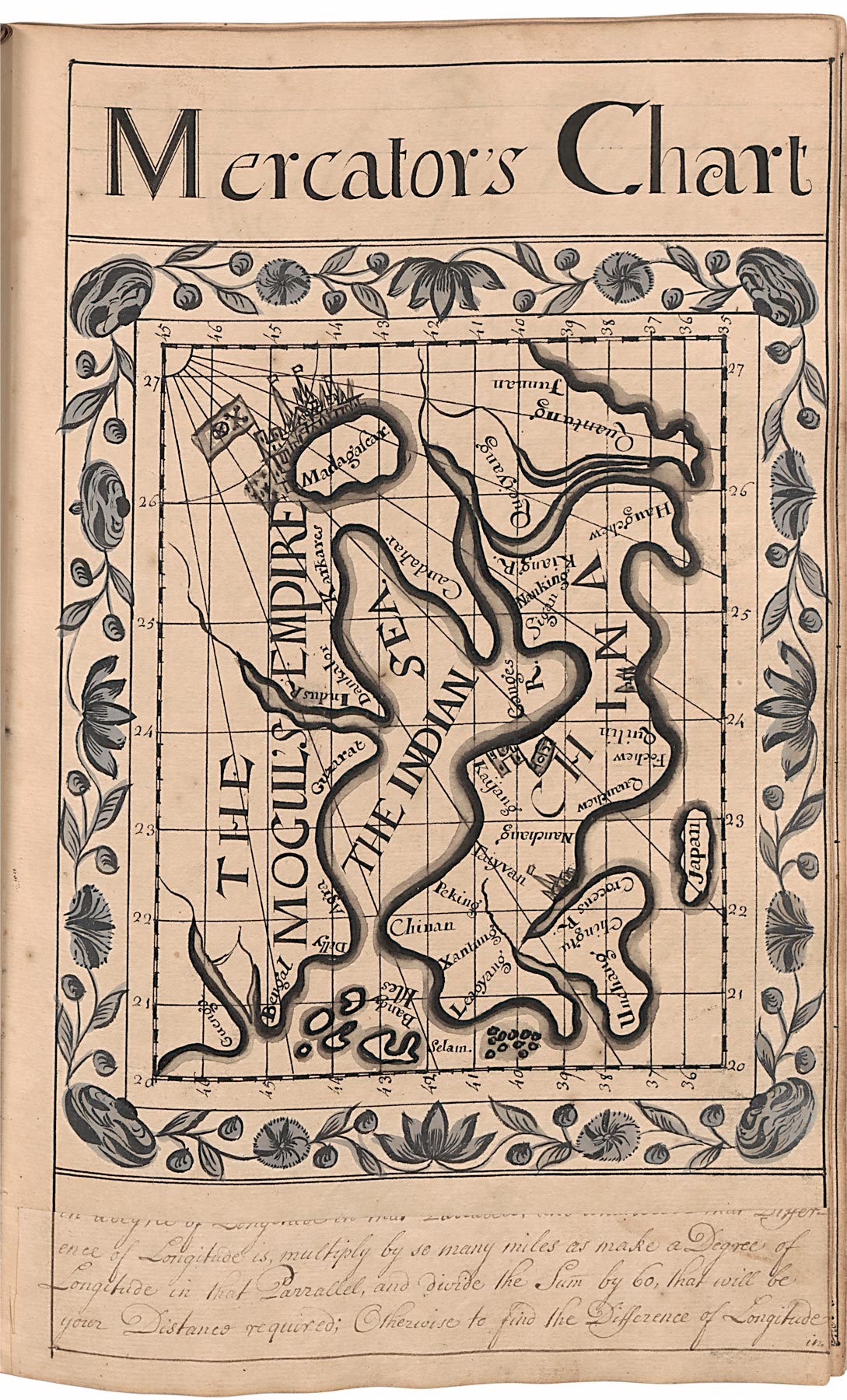

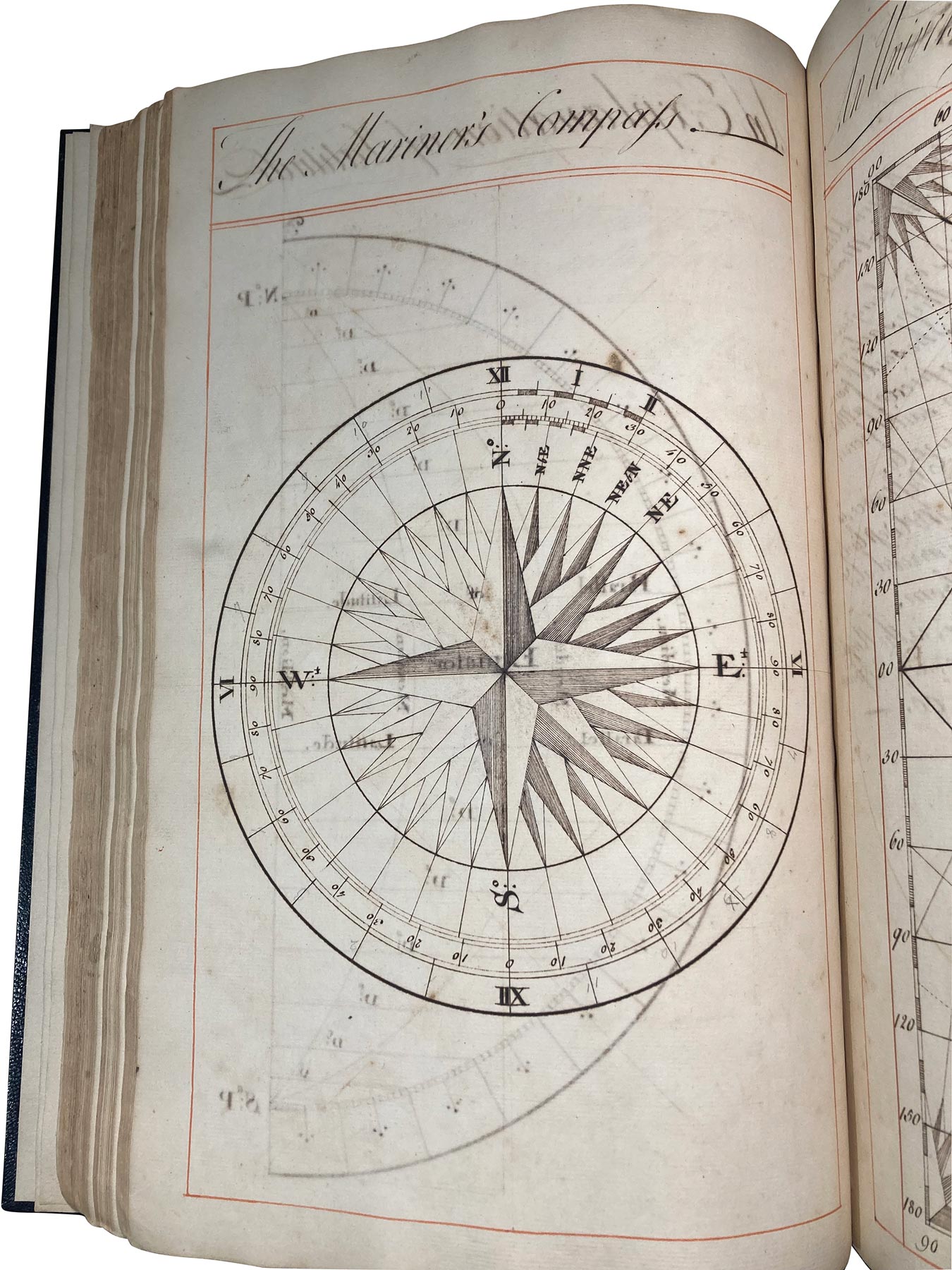

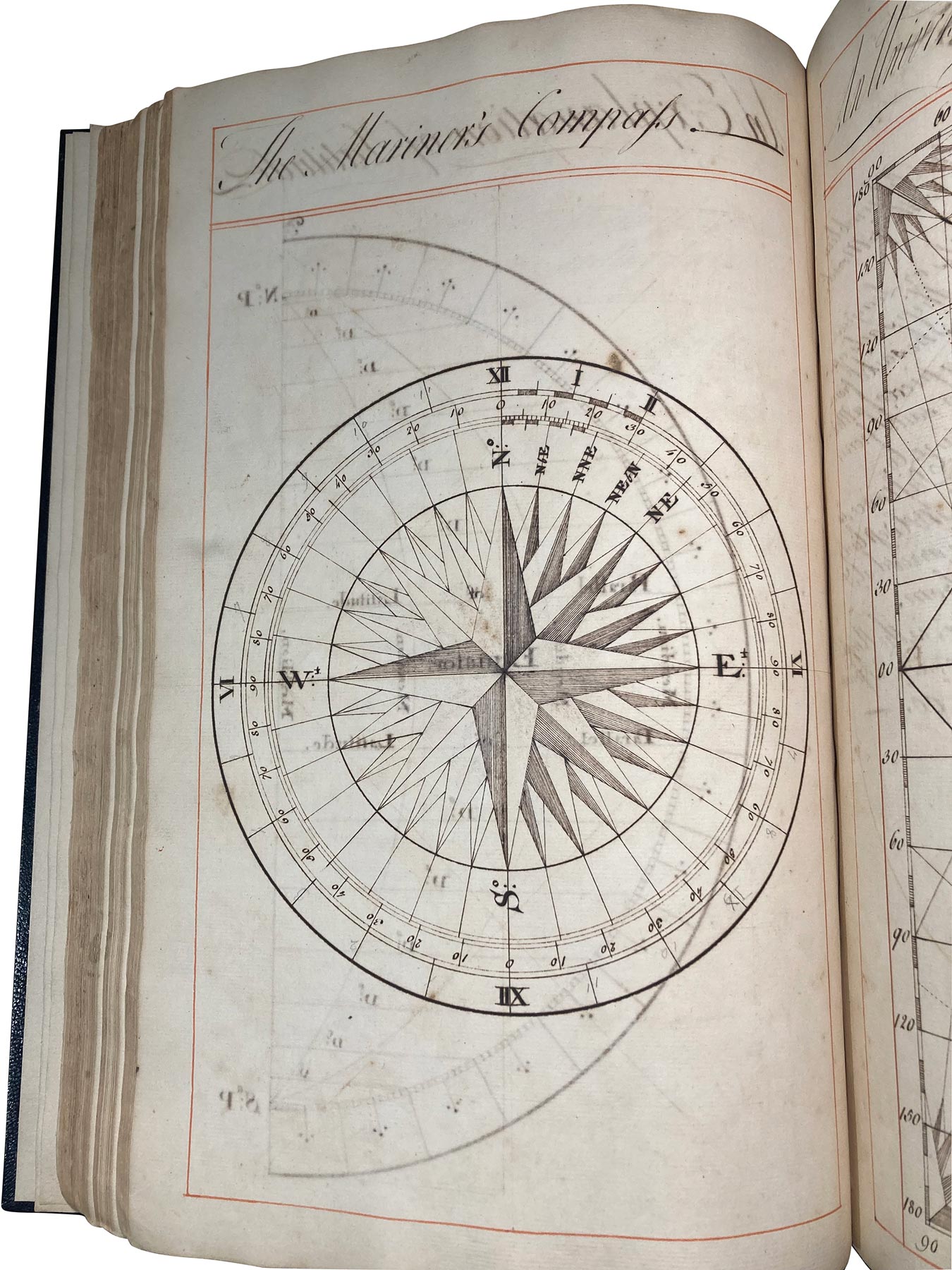

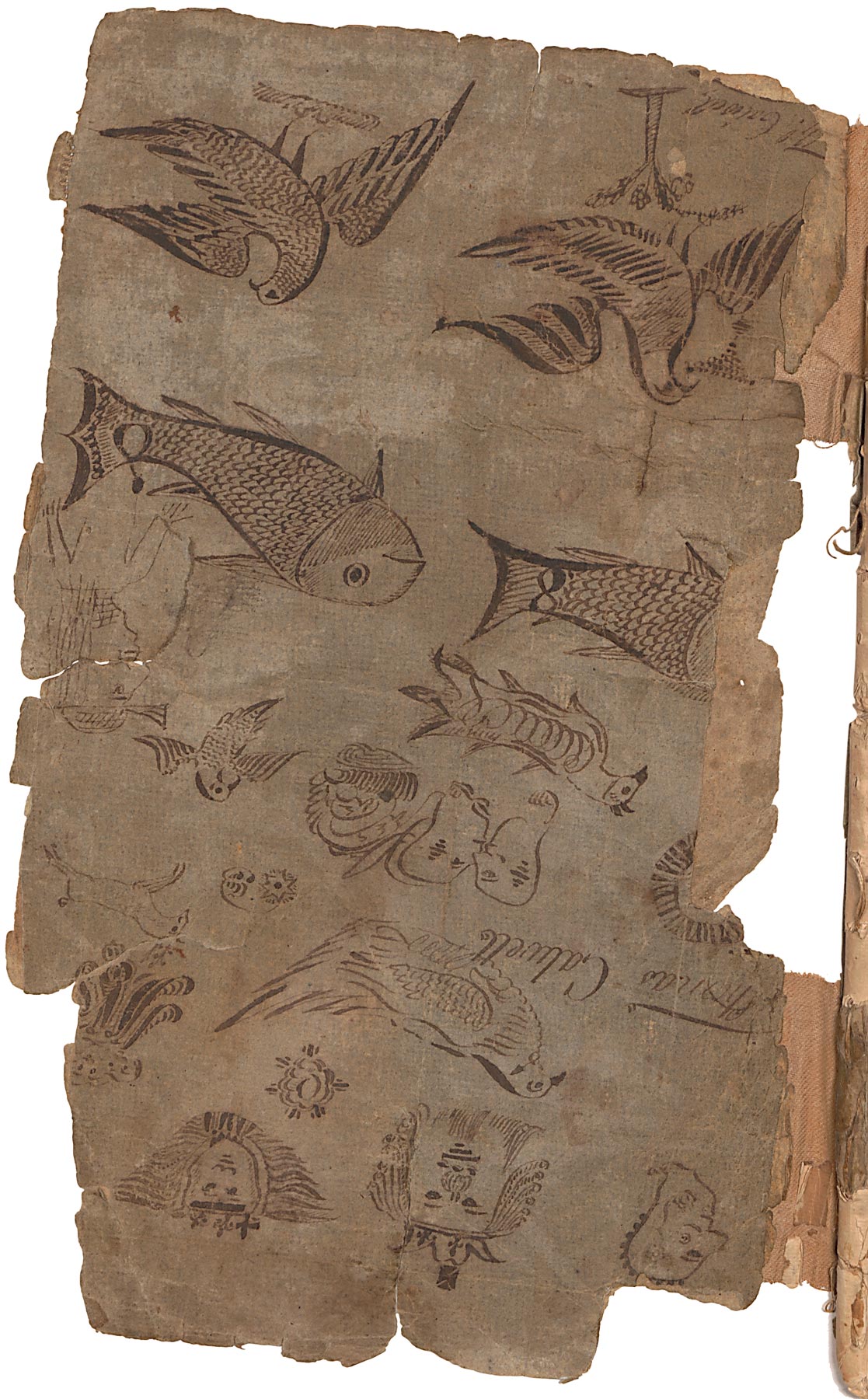

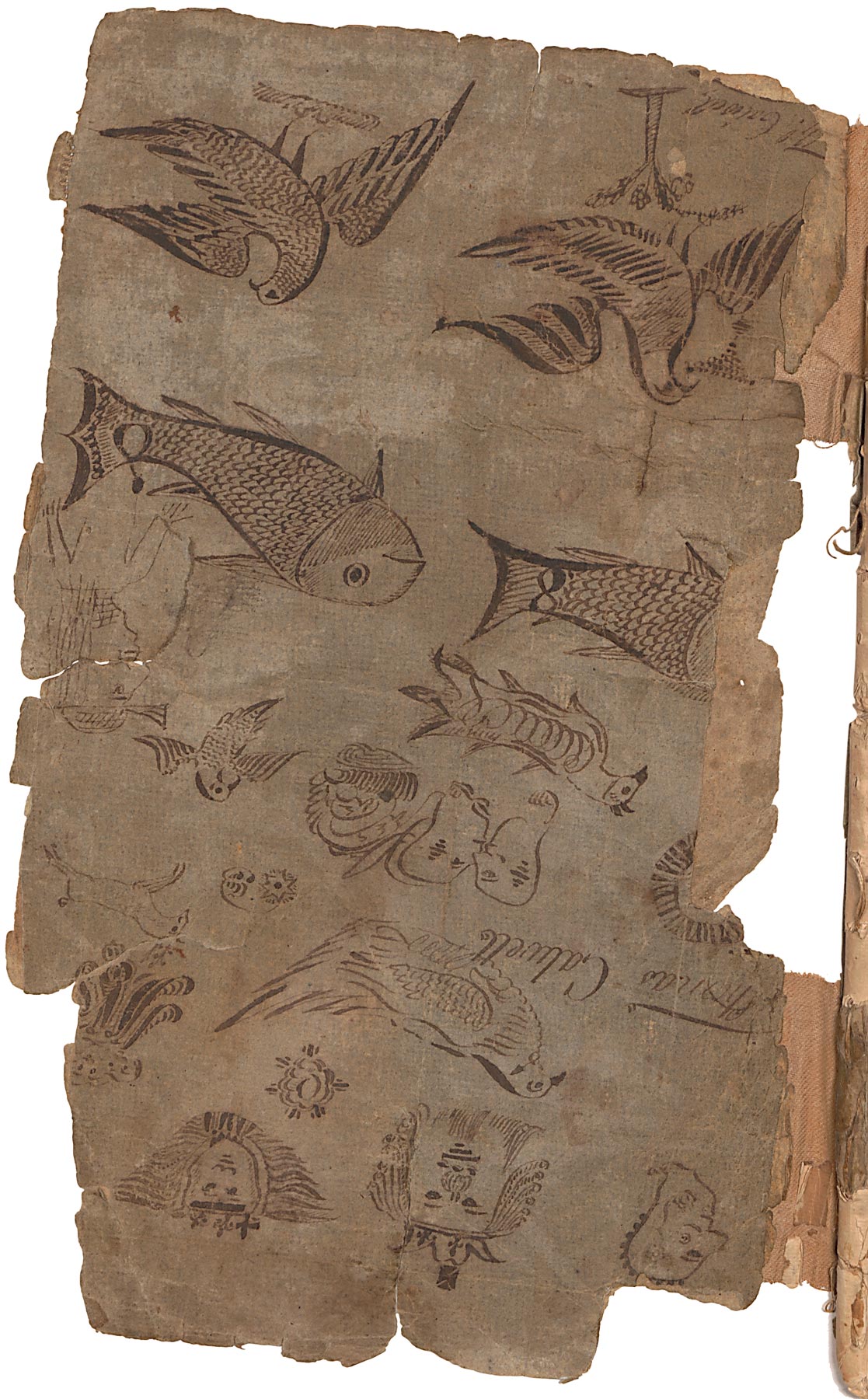

When it comes to bold and vivid graphic design in colonial America, the copybook created by New Jersey schoolmaster Thomas Earl in 1740 and 1741 is without precedent. Earl’s pages are simply brighter and more exuberant than virtually any other surviving work. On occasion, he even devotes entire pages just to the titles of his lessons, confirming he was first and foremost a devotee of the visual arts. By contrast, the copybooks of his American contemporaries were executed almost entirely in pen with iron gall ink on plain laid paper, and other than occasional doodles, demonstrate little attention to the aesthetics of individual pages (Figs. 1, 2, 3a, 3b).

This is an excellent example of the kind of embellishments one can find in student exercise books from the earliest years of this country.

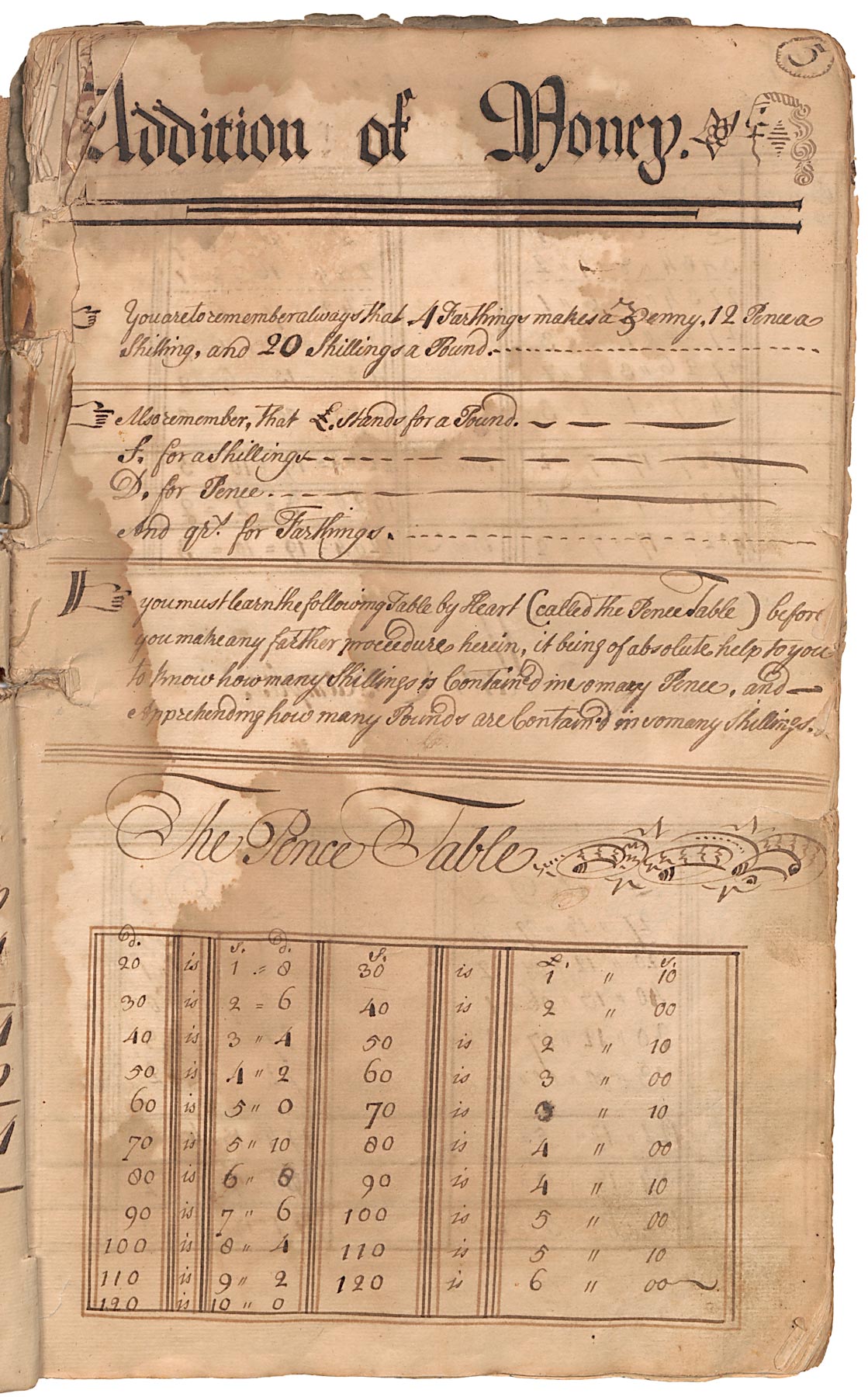

Copybooks, often referred to as ciphering books, played a key role in eighteenth-century education in colonial America. They were handwritten manuscripts prepared by schoolmasters for students to transcribe. As they copied pages, students learned penmanship and how to solve a myriad of practical problems that required mathematics and navigational knowledge. As they did so, they also created their own books to refer to when needed.

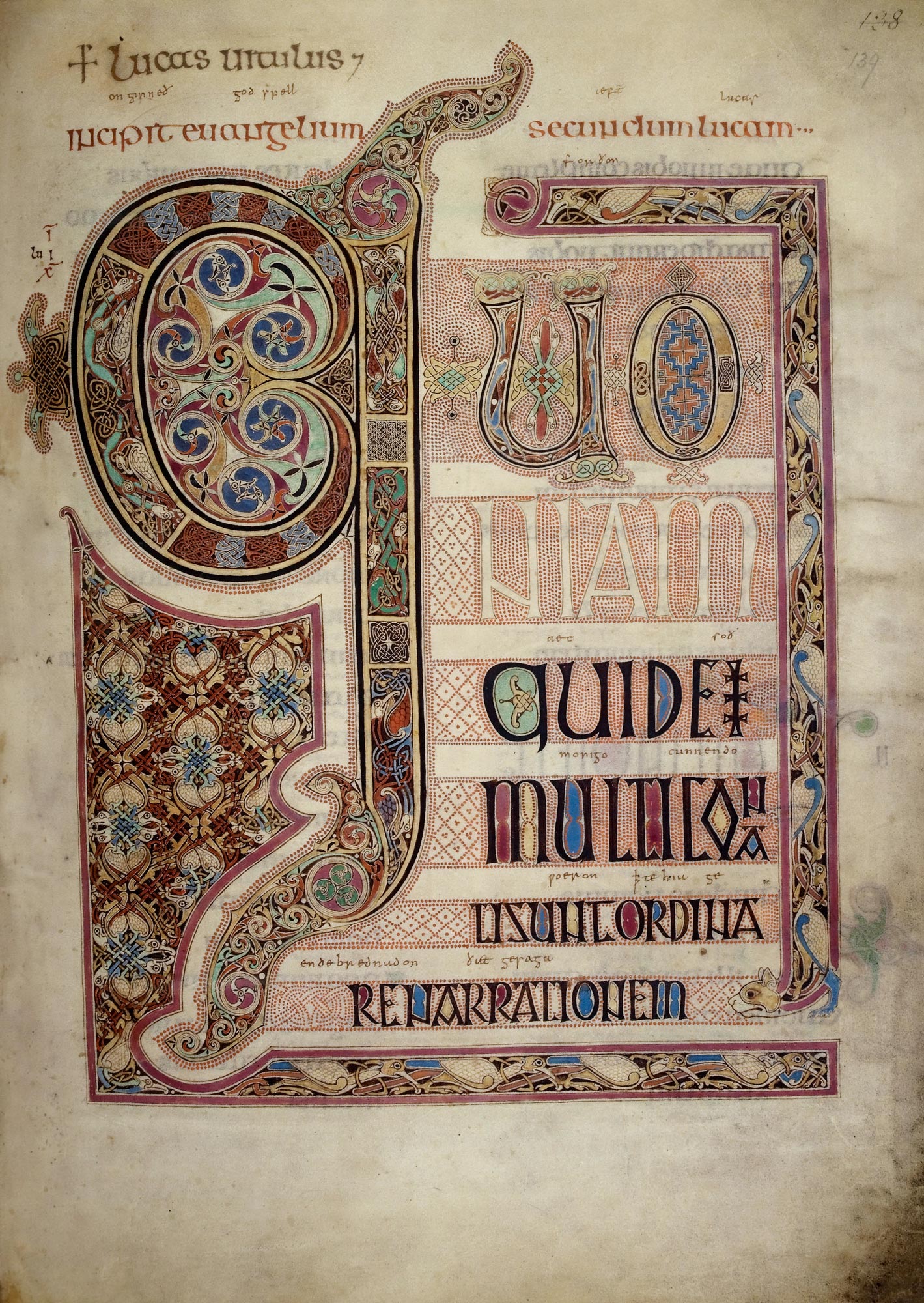

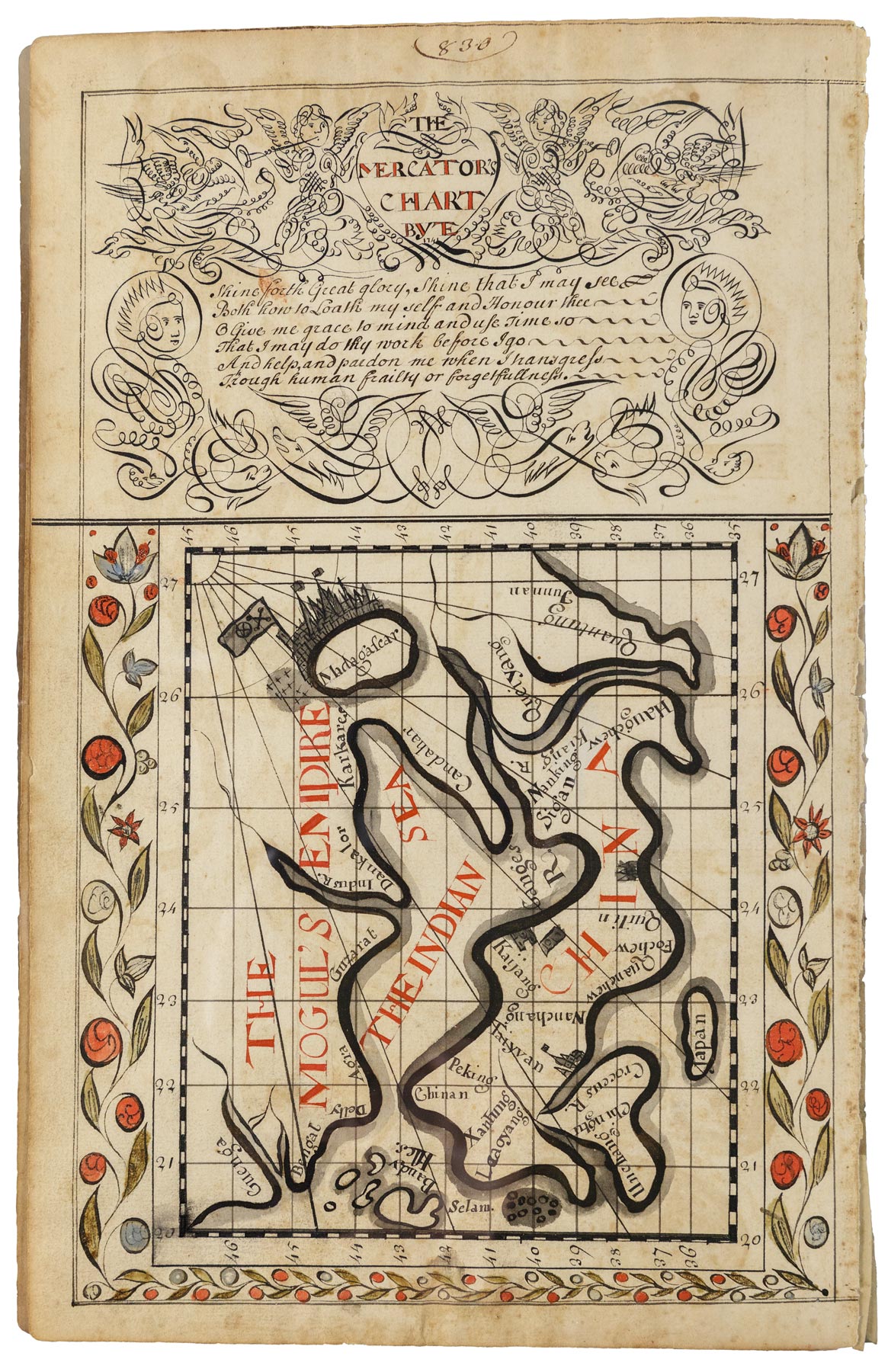

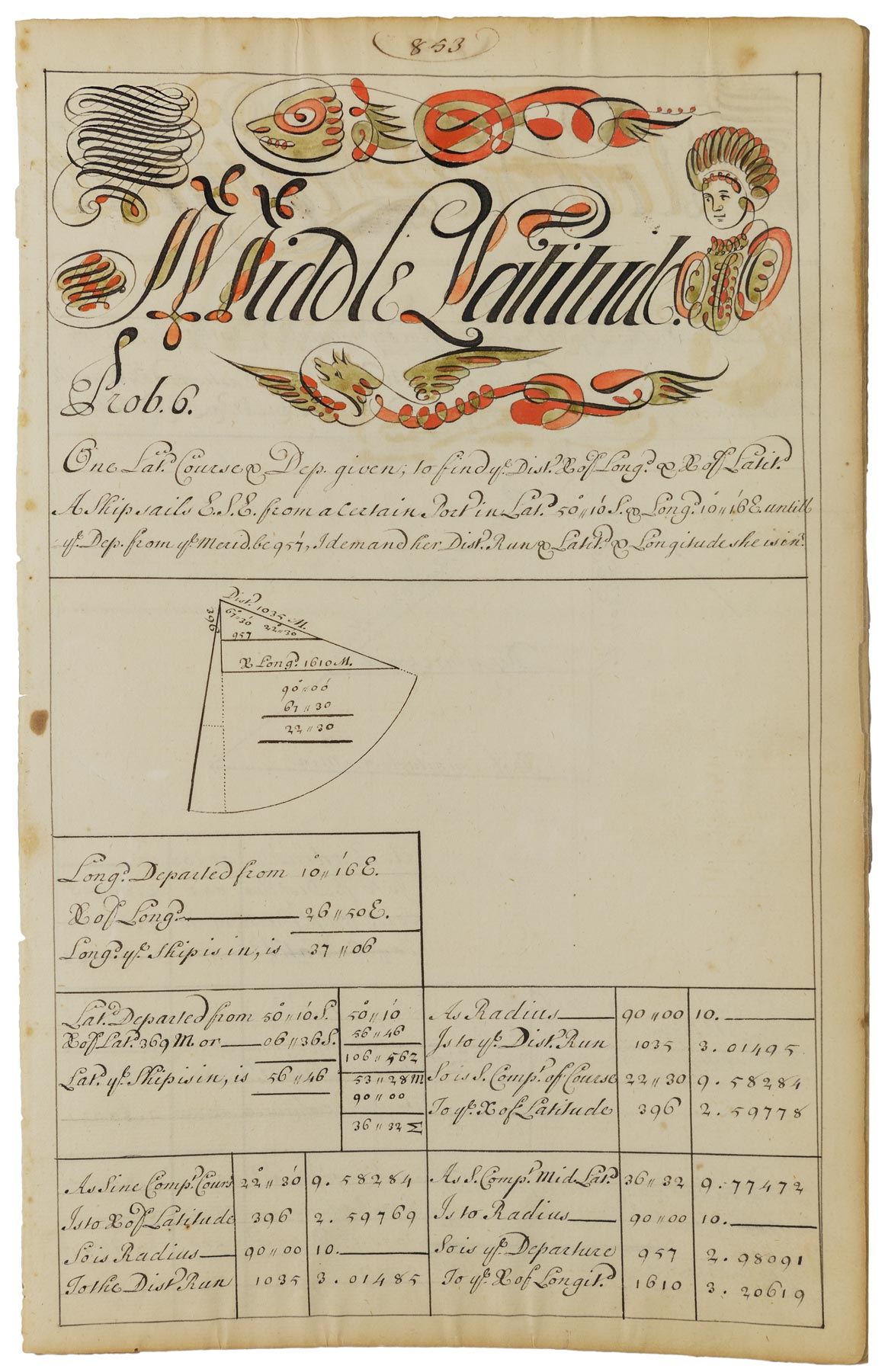

Enhanced by their remarkable state of preservation, Earl’s pages explode with dazzling color that greatly intensifies the intricacy of his designs. Some of his more elaborate pages are reminiscent of the “carpet pages” found in medieval manuscripts, such as the Lindisfarne Gospels (held in the British Library) or the Book of Kells (at Trinity College, Dublin), painstakingly created in Great Britain by clergy for devotional purposes.1 The aesthetic Earl embraced is so unusual for colonial America and varies so much from his 1727 copybook’s muted primary color palette and somewhat staid embellishments, one wonders what may have inspired him to adopt such an extravagant and painterly manner (Figs. 4, 5, 6, 7).

From the very first pages of his 1740–41 copybook, it is clear he learned graphic design by studying the English masters of calligraphy, whose work formed part of a lineage dating back to the writing books of the early Renaissance and medieval manuscripts.2 By carefully copying their designs, Earl was not only building his repertoire of skills, but also exploring a way to introduce aesthetic delight and excitement into the lessons he was preparing for his students to copy. He was also clearly enjoying himself by proceeding in this manner.

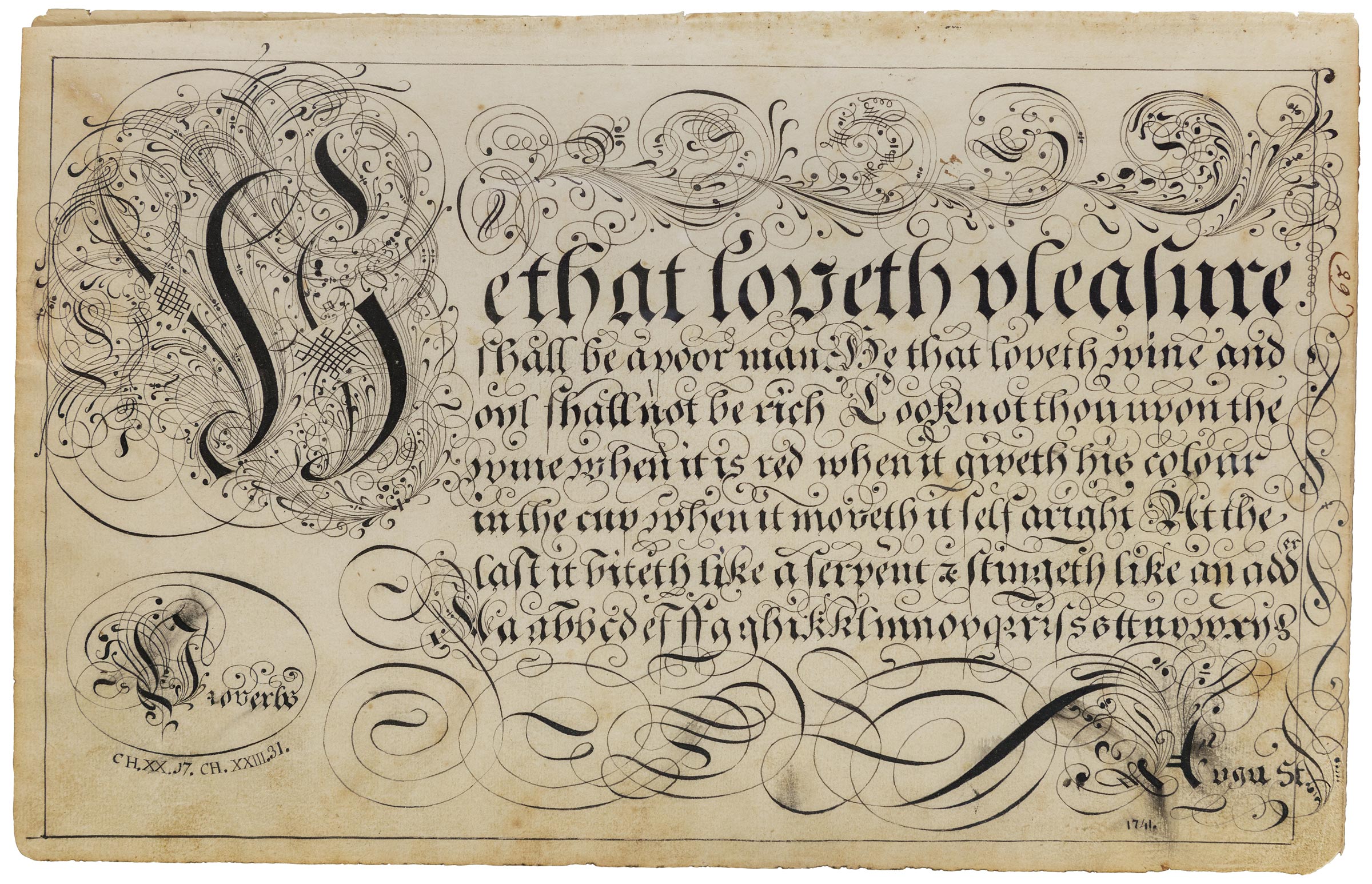

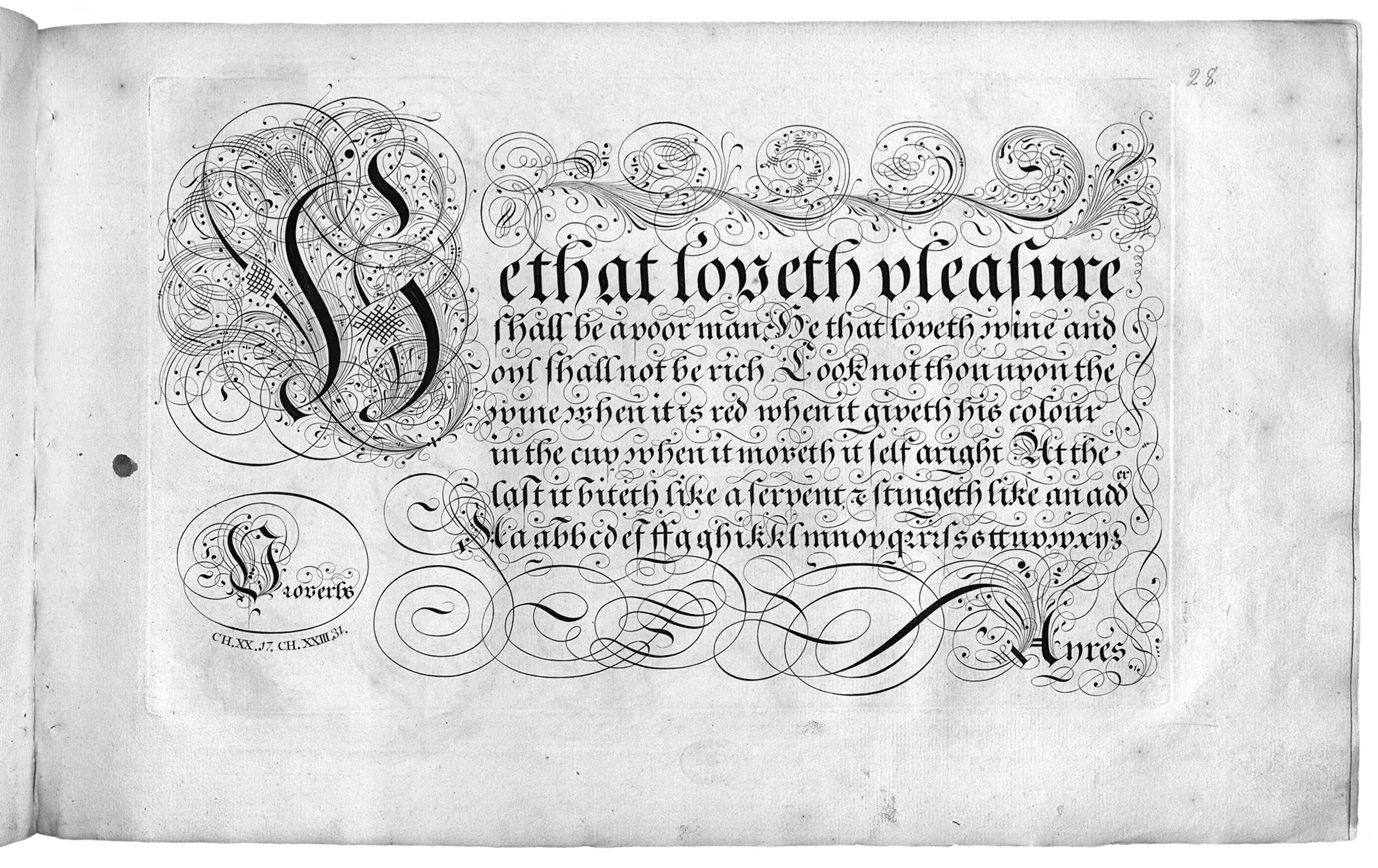

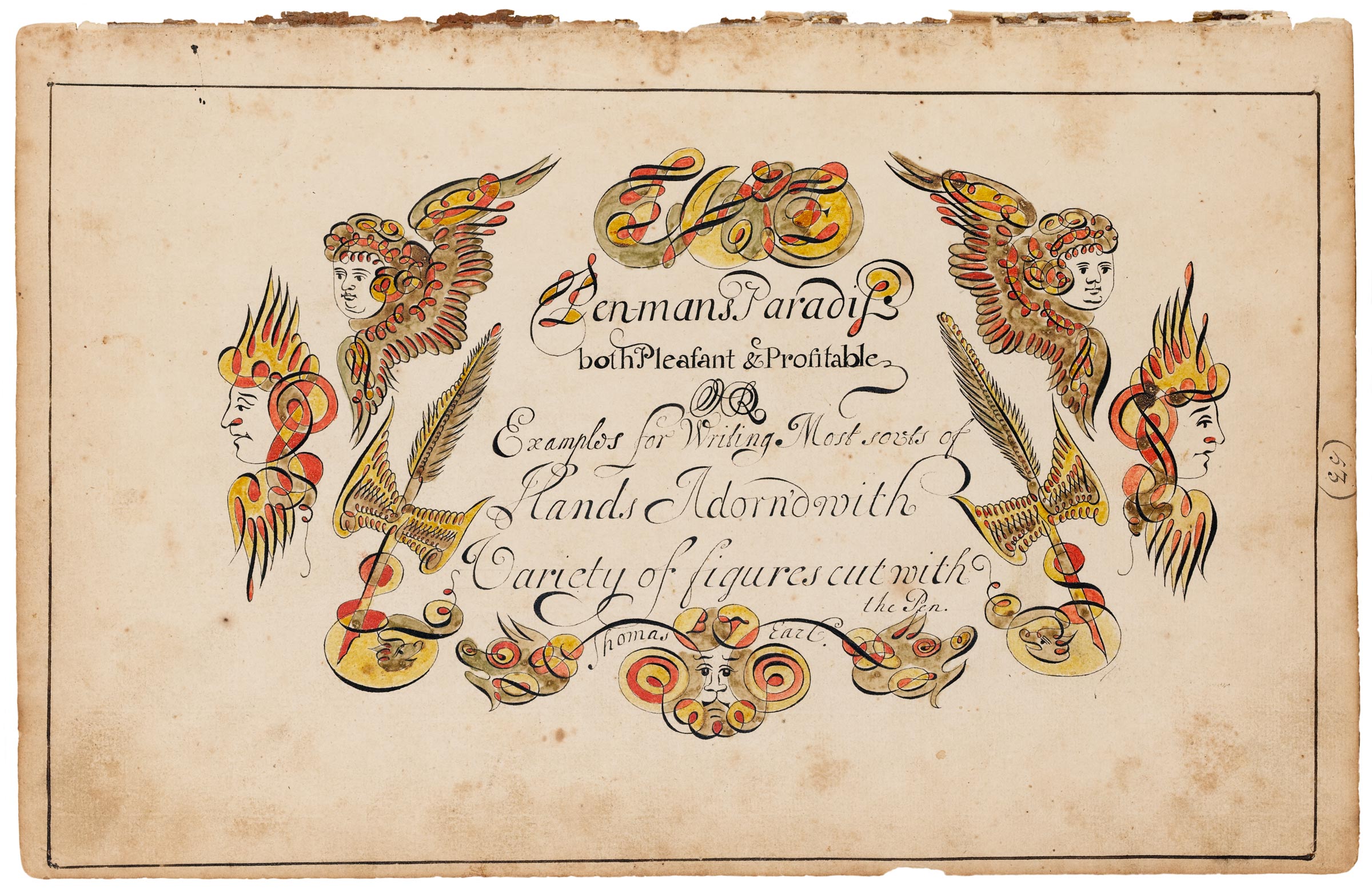

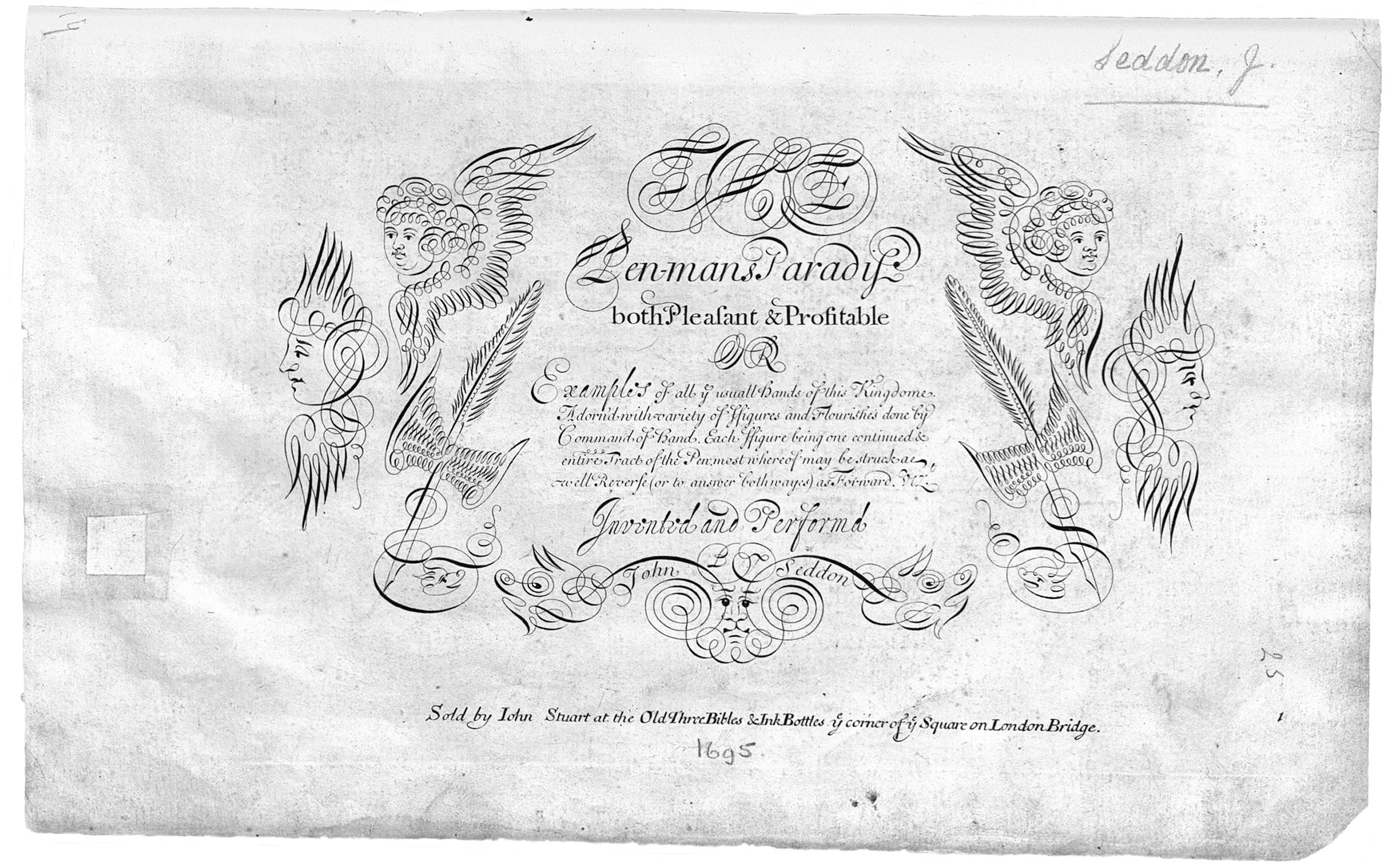

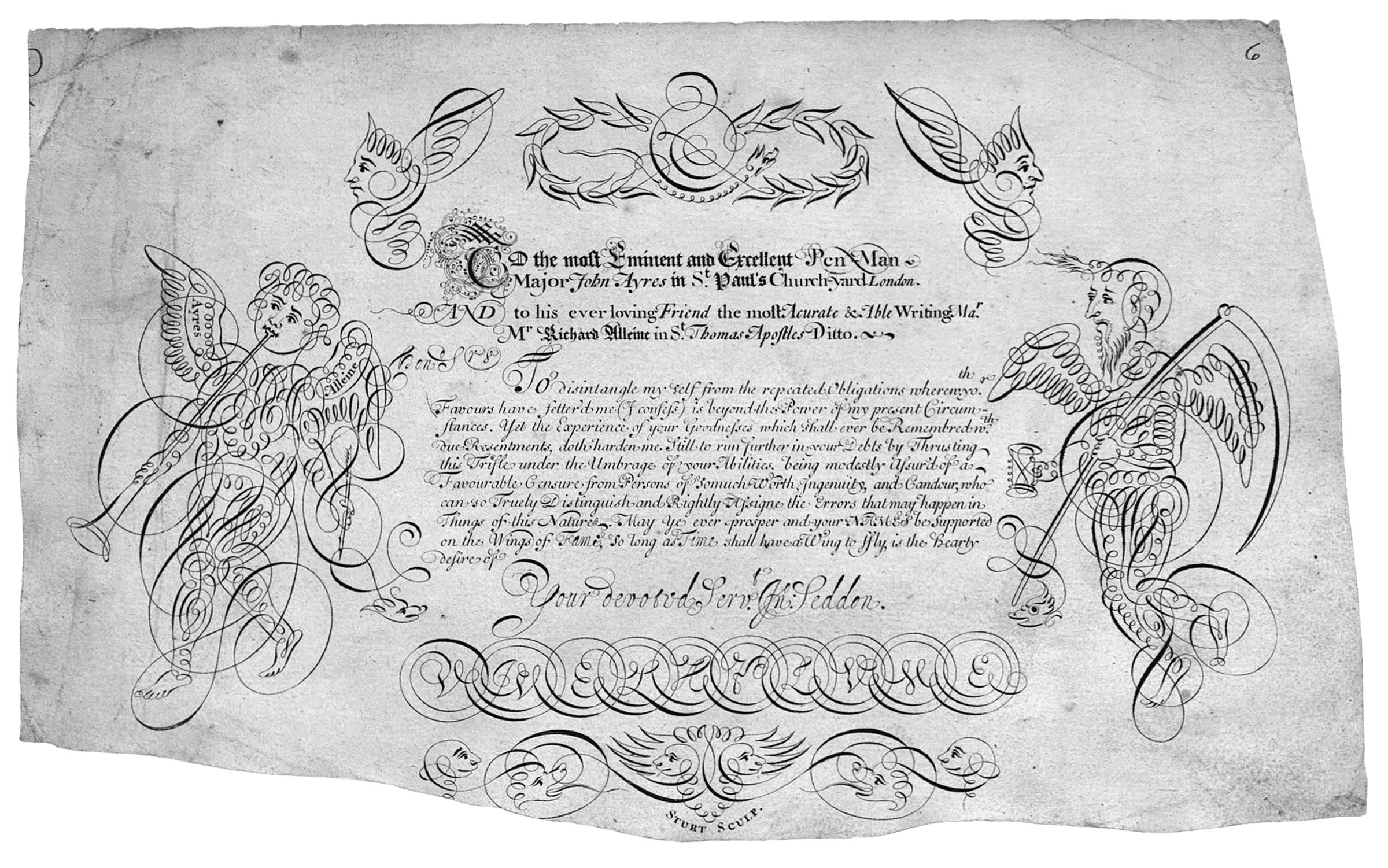

Earl’s page 29 is an exact copy of page 28 from A Tutor to Penmanship (Figs. 8, 9), John Ayres’s 1695 calligraphy book, widely adopted by schoolmasters.3 Pages from the copybook of Philadelphia resident Joseph Milnor (1718–1787) confirm that he, too, drew from Ayres’s book for his penmanship lessons.4 A further thirty-four pages of Earl’s book are copied directly from plates in John Seddon’s 1695 Pen-man’s Paradise: Both Pleasant and Profitable. Seddon (1644–1700) had served as the writing master of Sir John Johnson’s free writing school in London and was considered the premier calligrapher of his time. Still his best-known book, The Penman’s Paradise featured plates engraved by John Sturt (1668–1730), the leading engraver of English books on calligraphy, along with an engraving by the master himself. As one critic observed, “Seddon exceeded all of our English penmen in fruitful fancy and surprising invention in the ornamental parts of his writing.”5

Comparing Earl’s interpretation of title page of The Pen-man’s Paradise with the original, one can see how Earl adapted Seddon’s design and motifs and inserted his own simplified text and name at the bottom of the page (Figs. 10, 11). Earl also combined elements from Seddon’s pages with material found in other printed sources. For instance, on page 55 he replicated the layout of Seddon’s dedication page, quoted the first four verses of William Mather’s 1727 Young Man’s Companion, and added his own name twice (Figs. 12, 13).6

After page 120, Earl’s focus shifts from calligraphy to lessons in mathematics and its practical applications. Just as his inspiration for calligraphy was drawn from English writing masters, for these lessons he drew on English printed sources, includjng John Mellis’s Arithematic (1662), Will Leybourn’s Arithematick Recreation (1699) and Nine Geometrical Exercises for Young Sea-men (1669), and John Ward’s Mathematician’s Guide: Being and Plain and Easy Instructions to the Mathematicks in Five Parts (1728). The period of Earl’s education in England coincided with the flourishing of English publishing, while the colonies still relied heavily on imported books from London.8

Many of Earl’s ensuing topics are introduced with elaborate title banners highlighted with watercolor, and some topics are introduced with titles that fill an entire page. Pages 128 to 393 are devoted to lessons in commerce, such as how to measure products, calculate losses and gains, establish the value of one’s crops or shipments, estimate labor costs, and barter and exchange currency.9 Occasionally, Earl’s lessons are presented in verse, such as “A Country spark address’d a charming she/ In whom all lovely features did agree” (page 279).10 Other pages are simply tables for calculating such things as interest rates (pages 308–13) and liquid measurements (page 431). Very seldom does he introduce extraneous subject matter into his lessons; one example is an account of the mass suicide at the siege of Yodfat (AD 67), taken from Josephus’s famous history, The Jewish War (page 456).

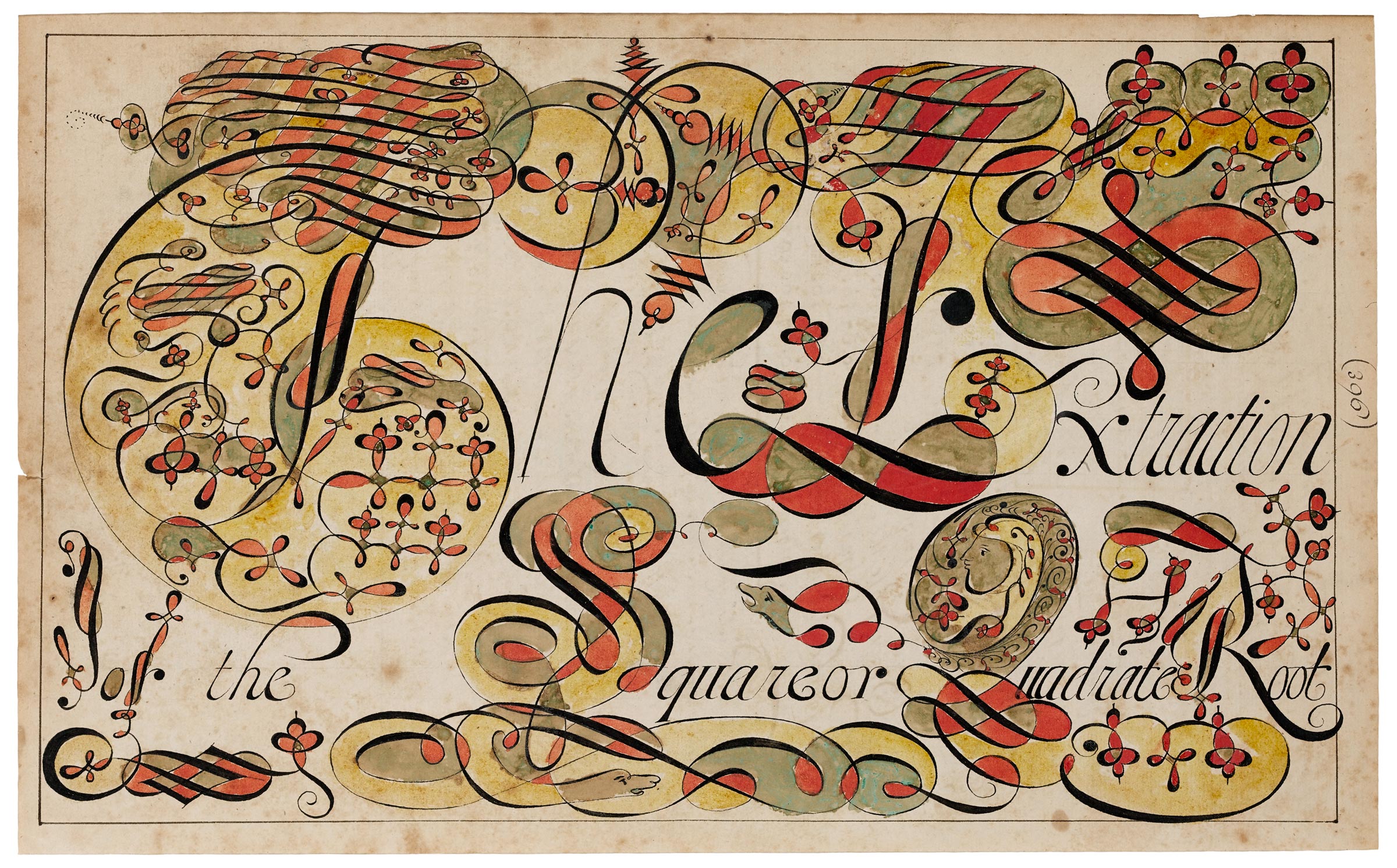

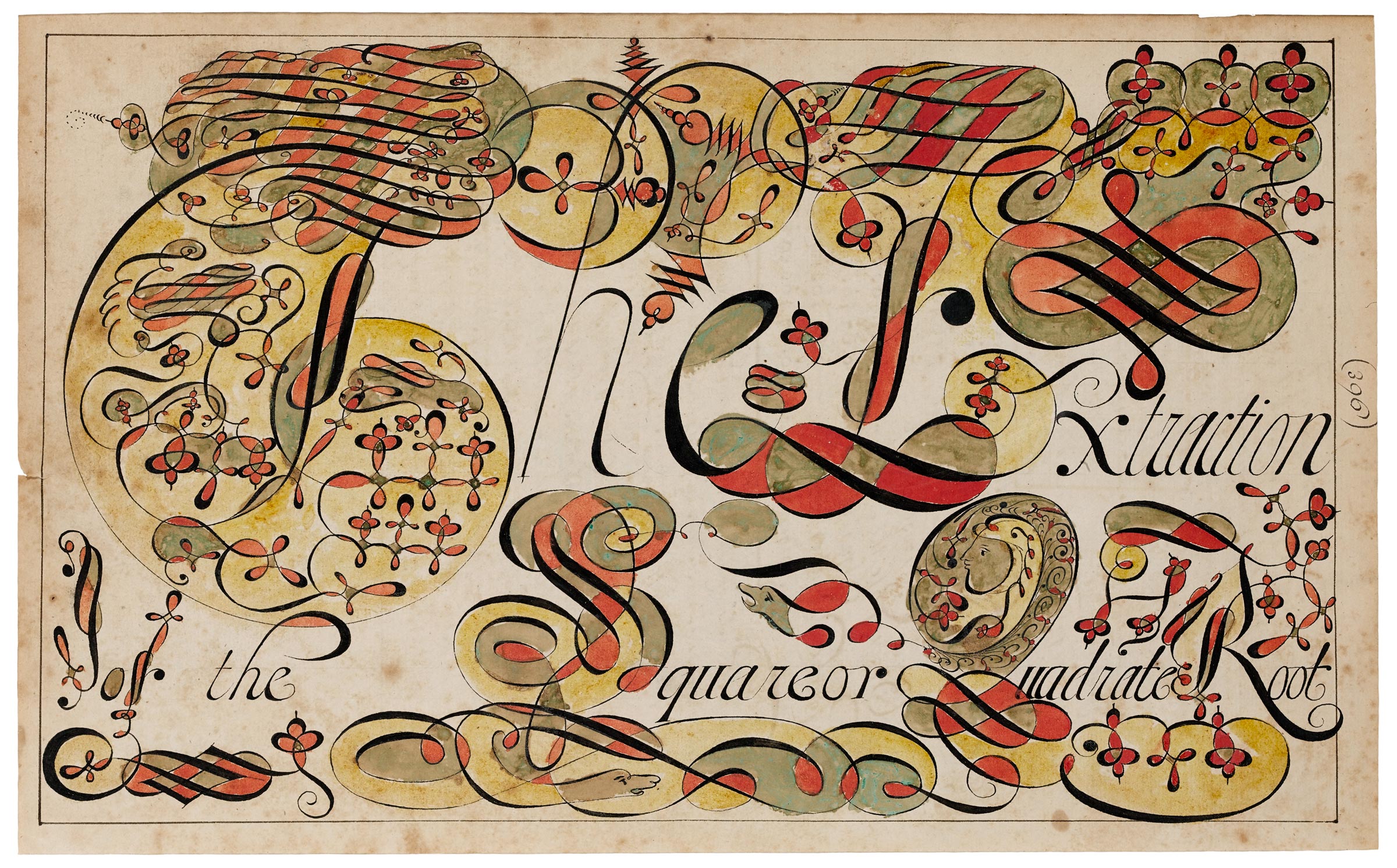

Often the playful design of his title pages provide a distinct contrast to the weightier mathematical problems that follow, for instance “The Extraction of the Square or Quadrate Root” (Fig. 7). Likewise, “A Collection of Pleasant and subtil [sic] Questions,” which introduces a series of 133 questions of increasing difficulty, followed by their solutions (pages 465–515). According to scholars Nerida Ellerton and Ken Clements, lessons such as “Substraction of Whole Quantities” (page 572) are found in less than ten percent of ciphering books.11 By page 693, “To Find the Time of High Water in Any Harbor,” Earl’s focus had shifted from mathematical and commercial to navigational subject matter. Some of the navigational lessons he included, such as “Middle Latitude” on pages 848–58, are rarely found in early American sources (Fig. 16). Again, this raises the question: who were his students that sought these advanced lessons?

How Earl gained access to such a broad range of source material is not known either. Books, in early America, were rare and expensive. If his lessons were not drawn from another schoolmaster’s copybook, he may have secured access to the libraries of a private citizen like James Logan (1674–1751) of Philadelphia. A Quaker merchant and secretary to William Penn, Logan built one of the colonies’ largest personal libraries, which he made available “to all properly introduced persons.” During these years, Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790) also set up a new subscription library (now known as the Library Company) to make books more accessible.

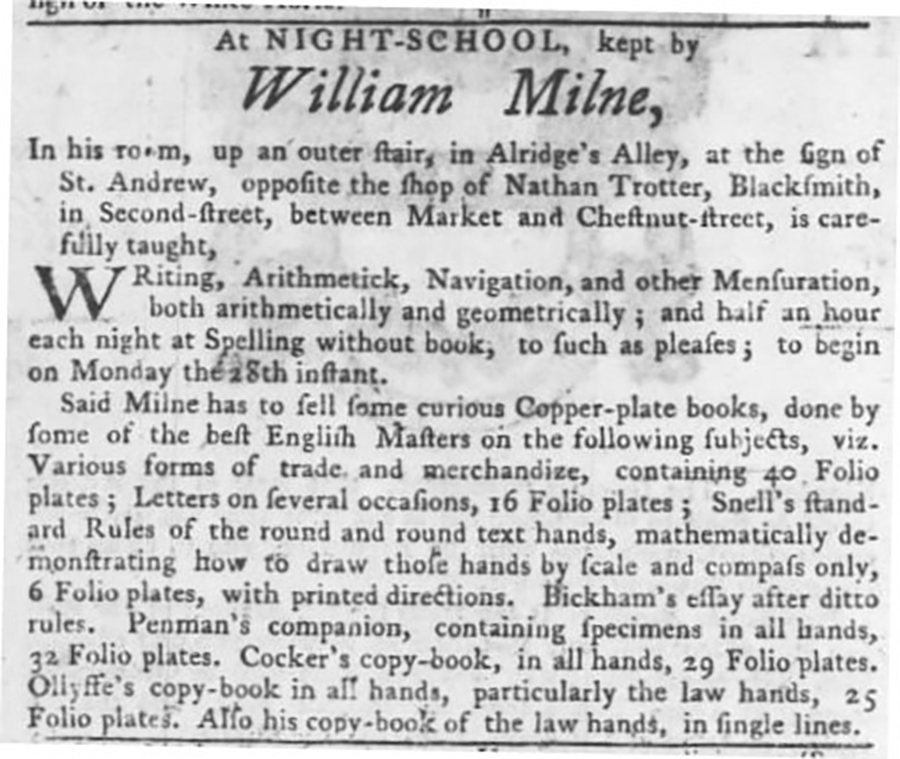

It is also possible Earl owned some of these books and may have even brought them with him when he sailed for America in 1731. Teachers were known to assemble their own collections.12 As noted earlier, Earl’s estate inventory listed books and other objects in his study which were valued at £18 16s 6d. Less than two weeks after Earl’s death on October 4, 1751, Philadelphia schoolmaster William Milne advertised that he was selling some “curious Copper-plate books, done by some of the best English Masters” (Fig. 17), including “32 Folio plates” from “Penman’s companion.”13

While many questions still remain, Earl was unquestionably a uniquely gifted artist with a steady hand, a keen eye for detail, and a deep understanding of how to use color to dramatic effect. He was also a dogged, even obsessive, copyist; the at least 910 pages of his 1740–41 copybook may well be a record for such an endeavor. He was not always careful, as he sometimes had to carry his words into a second line or interject them with an arrow. This can perhaps be attributed to the speed with which he must have worked.

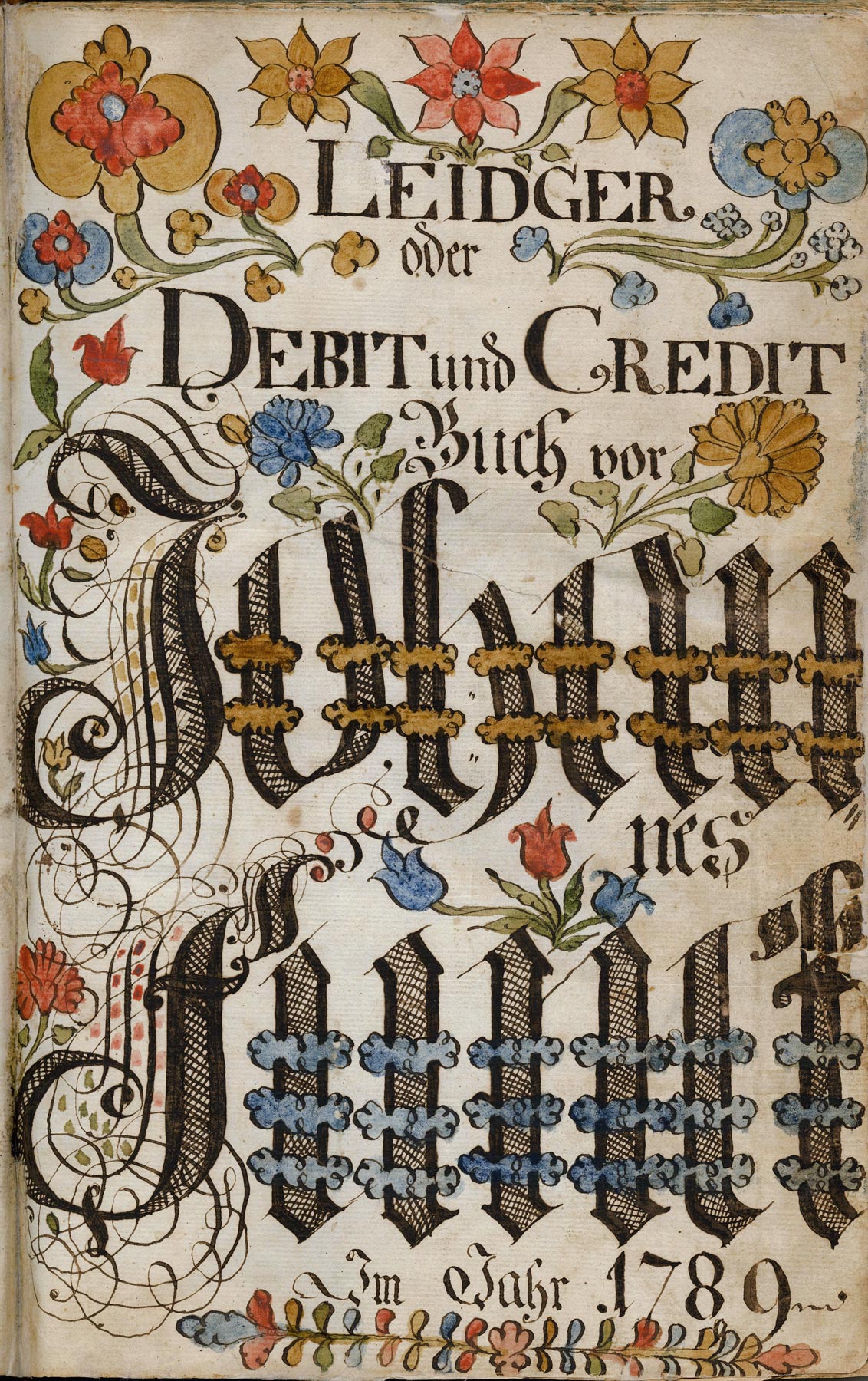

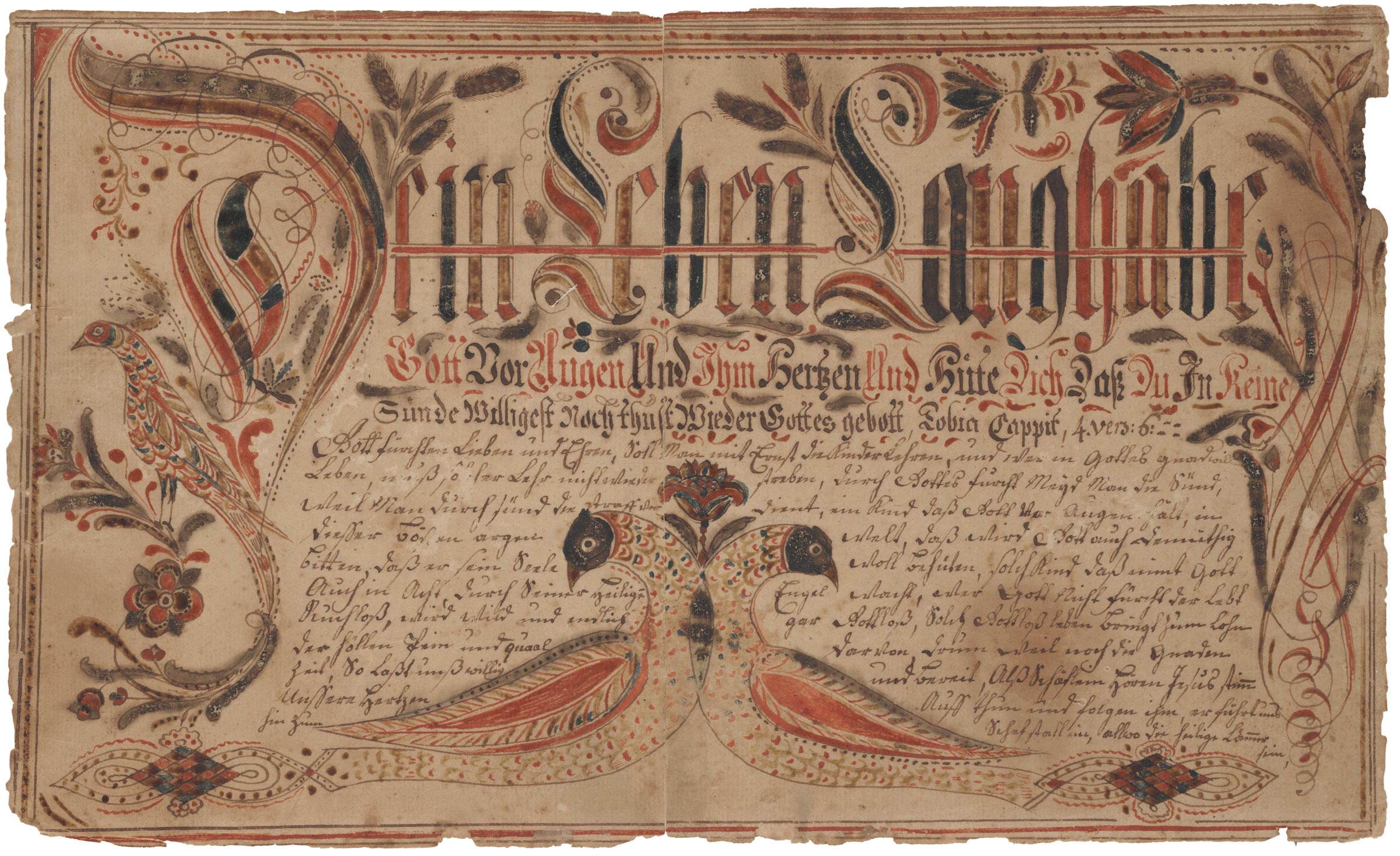

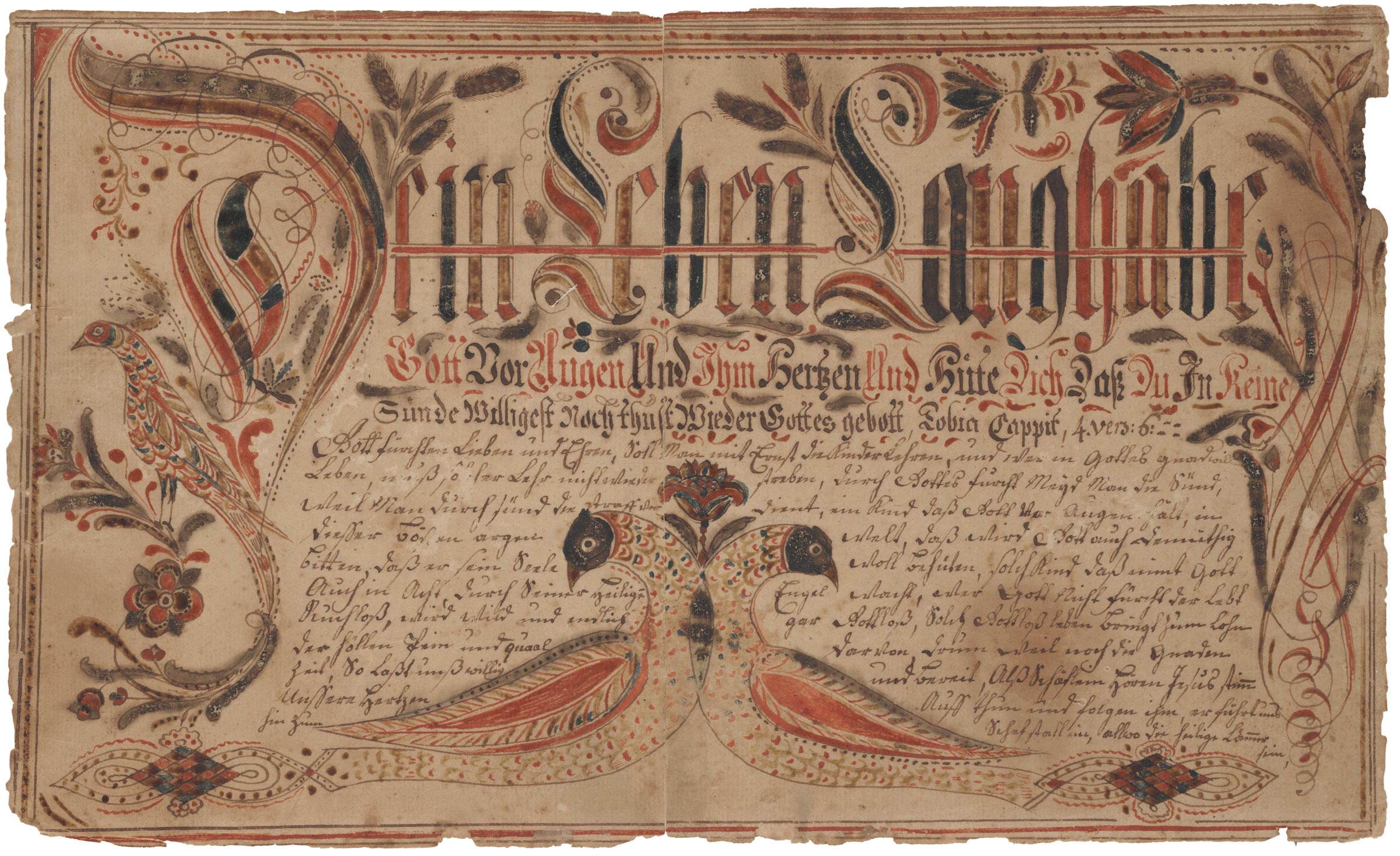

Although he drew heavily on others for his text, calligraphy, and charts, the detail and brilliant coloring of the pages of his 1740–41 copybook places him at the forefront of a new aesthetic for manuscripts in this country. Such intricacy, vibrancy, and exuberance have visual parallels to the Pennsylvania German manuscript art known as fraktur. They incorporated similarly lavish calligraphic flourishes and colorful ornamental embellishments into their works, so it is not surprising that Earl’s 1741 copybook has been described as an early American fraktur manuscript.14 They are of the same idiom.

But Earl was inspired by British pictorial traditions rather than Continental ones, and his masterpiece was created just as fraktur was beginning to be practiced in Pennsylvania (Figs. 18, 19).15 Earl was America’s first master of illuminated calligraphy, and his work stands above and apart from everything that came after his brief and largely unheralded career.

Acknowledgments

About the Author

1 These pages were dubbed “carpet pages” because of their resemblance to carpets from the eastern Mediterranean.

2 Encyclopedia Britannica, s.v. “writing manuals and copybooks (16th to 18th century),” by Ray Nash and Robert Williams.

3 John Ayres, A Tutor to Penmanship, or the Writing Master: A Copy Book Shewing all the Variety of Penmanship and Clerkship as Now Practiced in England (London, 1695).

4 Joseph Milnor, writing book, 1732–43, Newberry Library, Chicago, MS ZW 783.M632.

5 Dictionary of National Biography, ed. Sidney Lee, vol. 51 (New York: Macmillan, 1897), s.v. “John Seddon.”

6 William Mather, The Young Man’s Companion, or Arithemetick Made Easy, 13th ed. (London: S. Clarke, 1727), 69.

7 For information on Gerardus Mercator and his map, see National Geographic Resource Library, s.v. “Gerardus Mercator.”

8 Carroll Hopf, “Calligraphic Drawings and Pennsylvania German Fraktur,” Pennsylvania Folklife 13, no. 1 (Autumn 1972): 5.

9 On page 356, the value of various foreign coins is compared to English coins. The problems that follow all relate to exchanges between to merchants in London and cities in Europe, such as Naples, Antwerp, and Amsterdam.

10 Earl’s sixteen lines of verse were probably copied from The Ladies Diary, published in London by G. Robinson in 1710. On page 289, Earl again inserts verse in his lesson on “double position.”

11 Ken Clements, email correspondence with the author, November 2, 2020.

12 For example, schoolmaster Abiah Holbrook (1718–1769) presided over the South Writing School in Boston for more than a quarter century and assembled his own professional library, which is now housed at Harvard. See Ray Nash, American Writing Masters and Copybooks: History and Bibliography (Boston: Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 1959).

13 Pennsylvania Gazette (Philadelphia), November 29, 1750.

14 Advertisement in Antiques and Fine Arts 10, no. 1 (Spring 2010), 68–69.

15 The era of Pennsylvania German fraktur is generally considered to span 1740–1850. The earliest known fraktur made in Pennsylvania was at the Ephrata Cloister in Lancaster County during the 1740s.