Tributes in Paper from the City of Brotherly Love

Editor’s Note

In this essay, researcher Deborah Child examines a group of exceptional and intricate cutworks made in the second quarter of the nineteenth century with the goal of identifying the artist. Her exploration leads her to Philadelphia prisons and their wardens, visitors, and inmates. Child makes a strong argument that the artist is Abraham Eldred (c. 1794–1854), who made the work while incarcerated.

The essay identifies eighteen cutworks and is supplemented by an addendum which identifies five more examples, bringing the total body of work to twenty-three known examples.

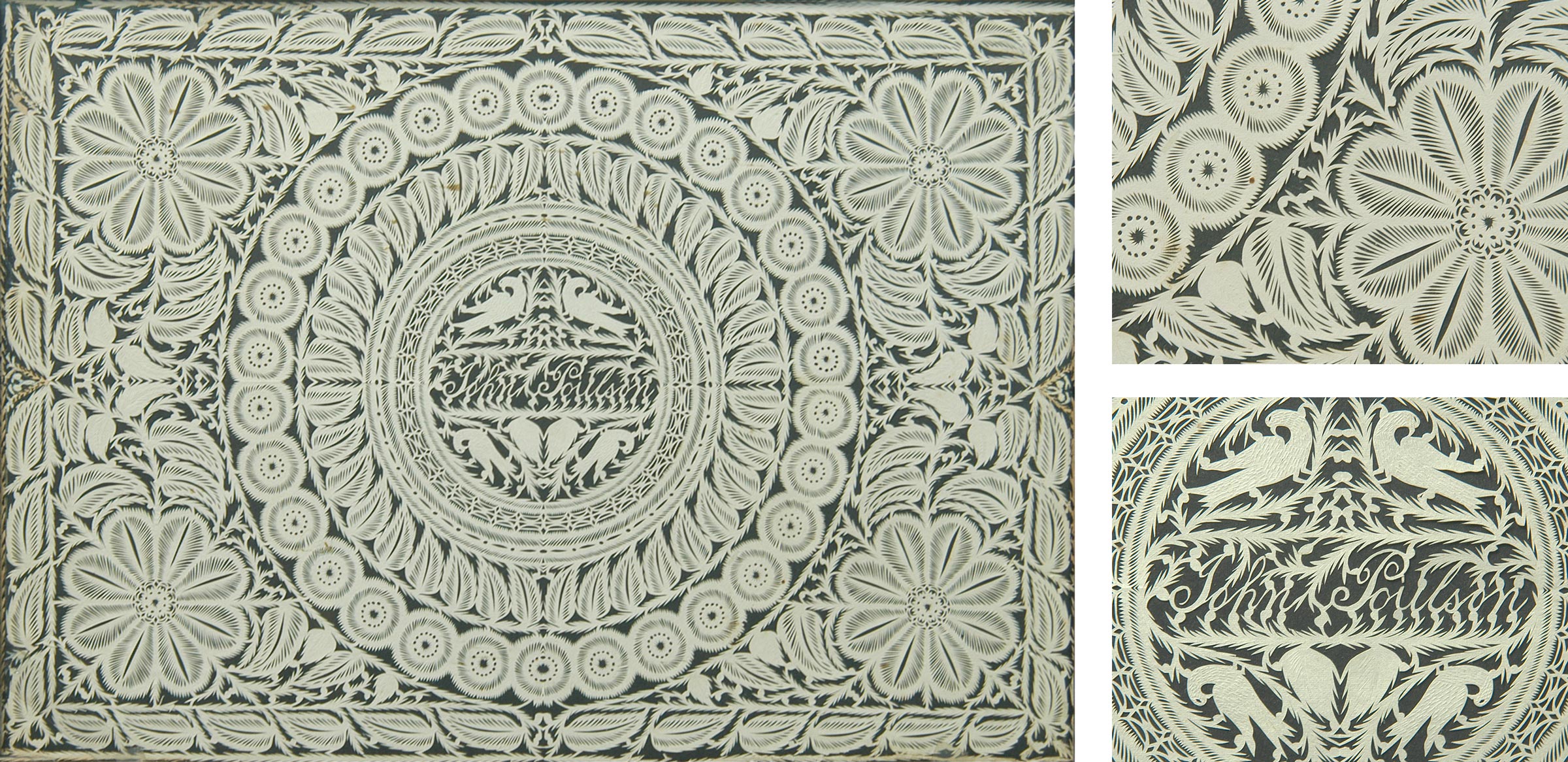

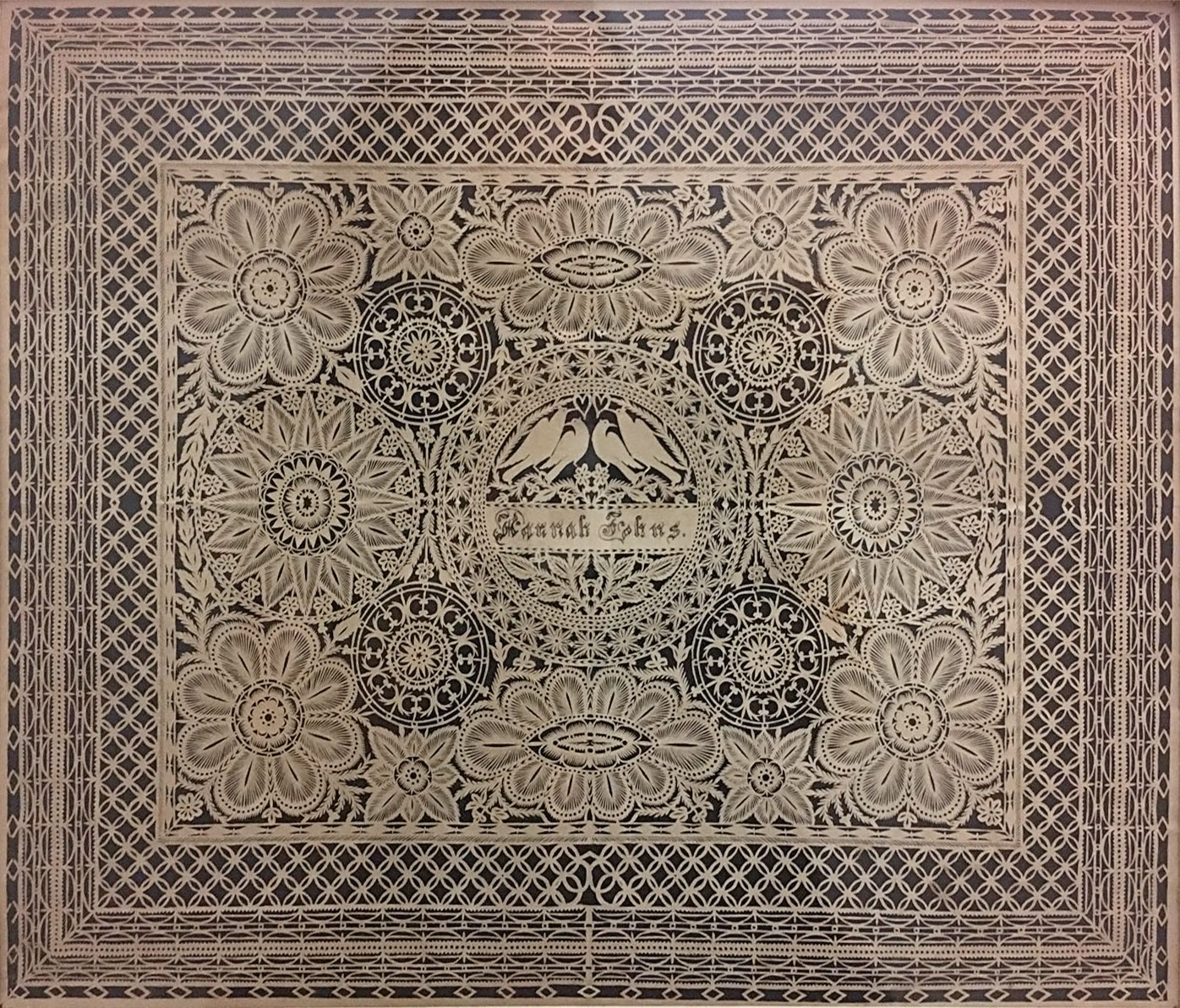

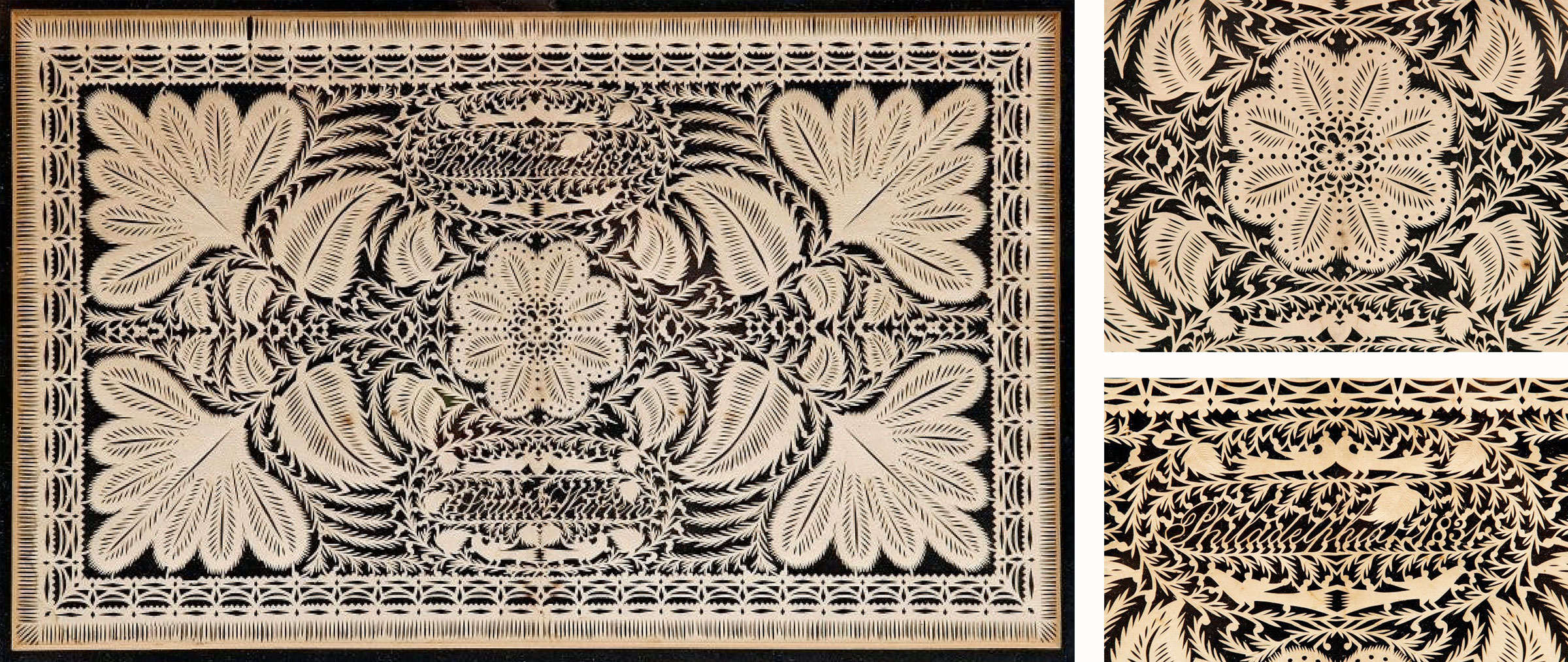

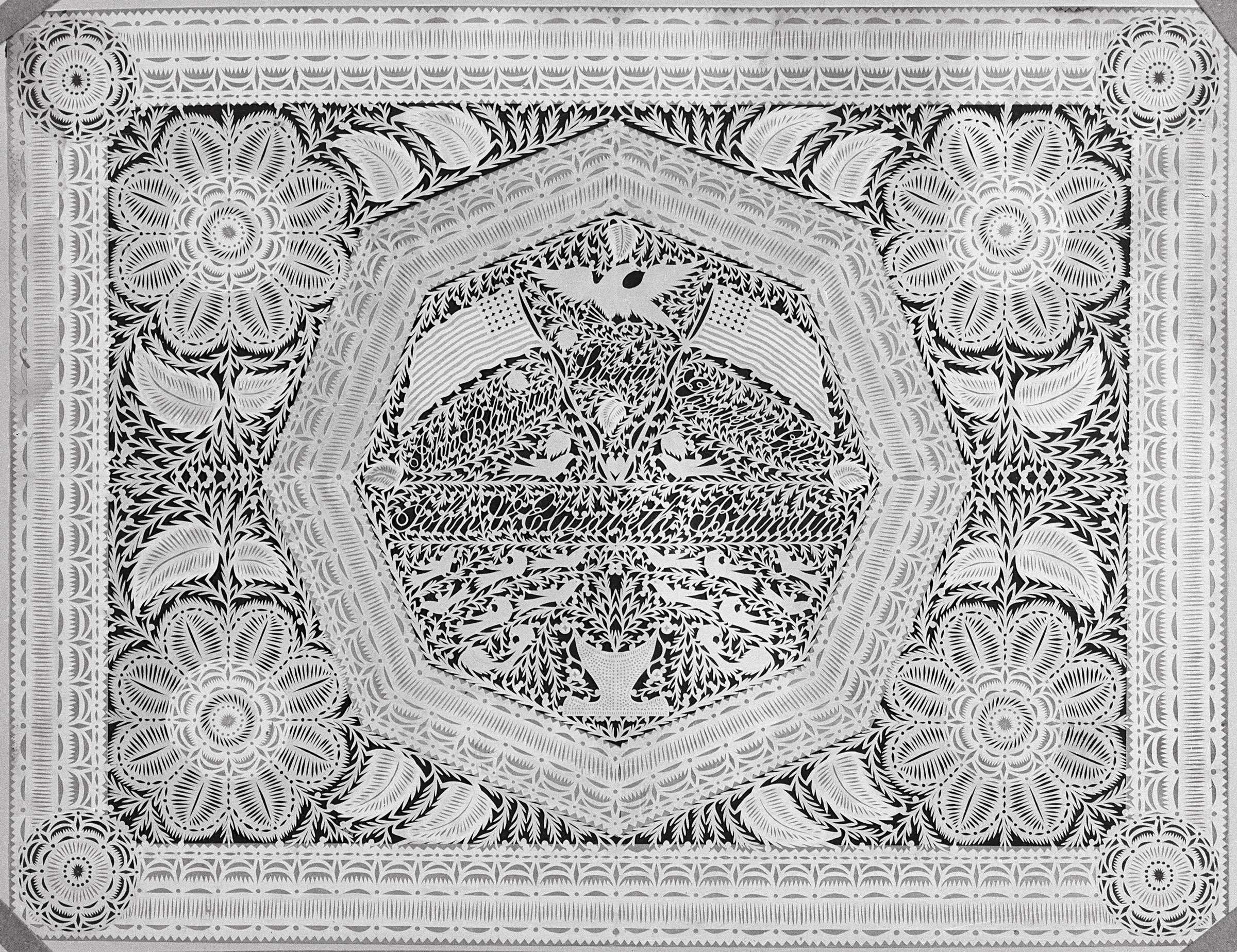

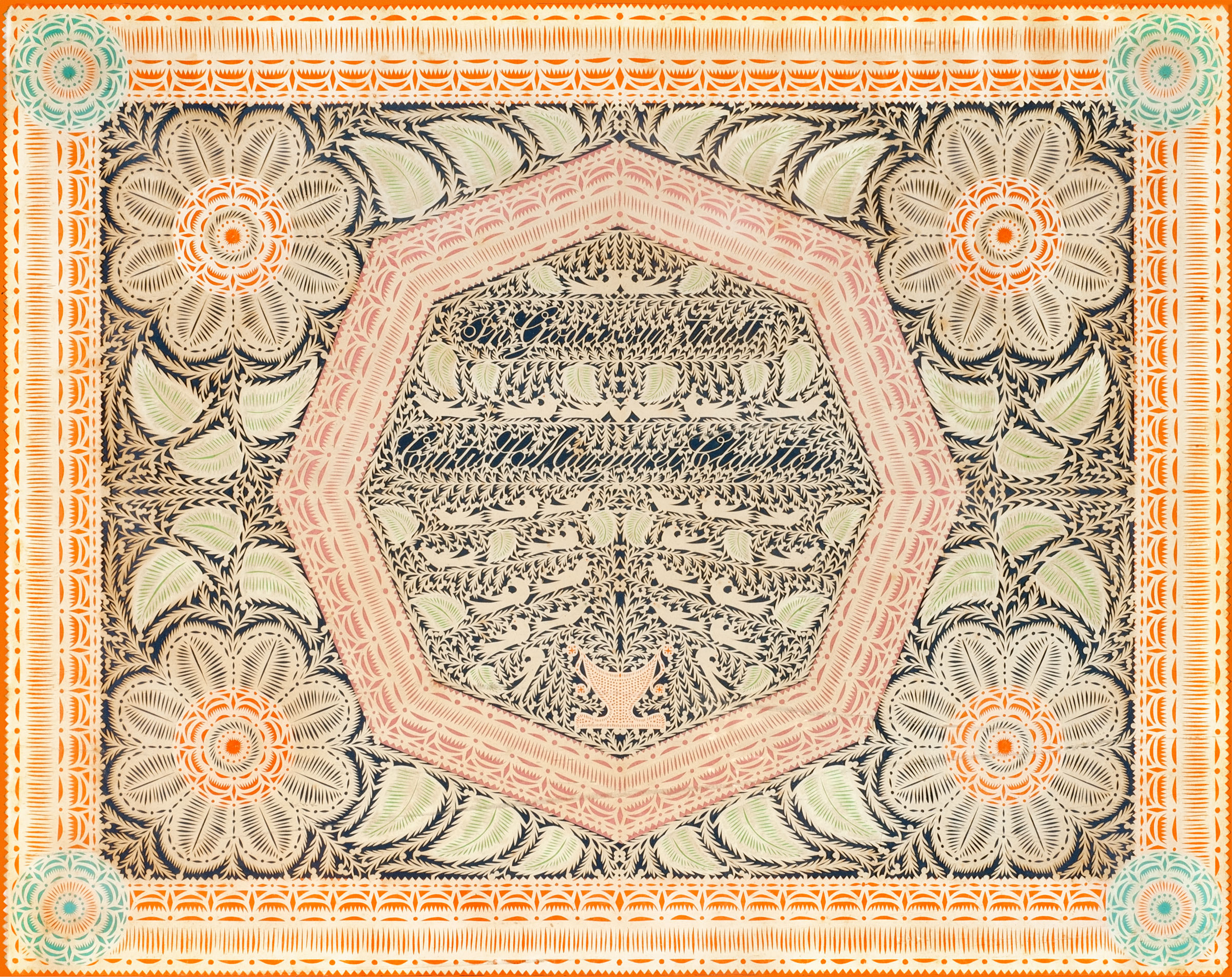

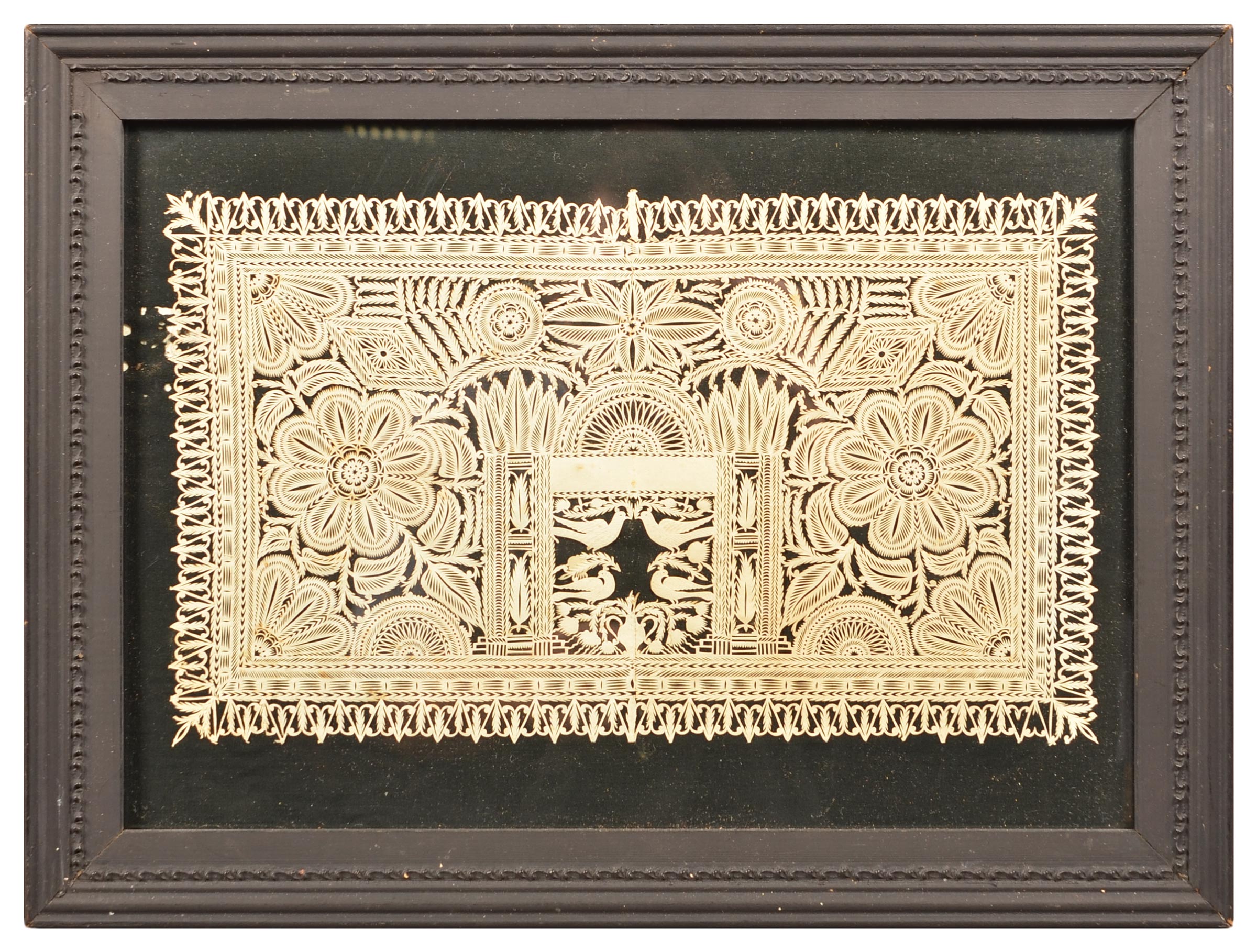

In the early nineteenth century, a master practitioner of the art of paper cutting in the city of Philadelphia made a technically unparalleled series of cutworks set within a rectangular framework incorporating circles and ovals. In each example, the paper was cut with such singular precision that its overall effect is comparable to the finest lacework. As scholar Lisa Minardi has keenly observed, this intricacy “involves not just cutting out designs but also slitting the paper and/or pinpricking to create texture and add to the overall incredibly delicate effect.”1

But what makes these works truly memorable is the maker’s ability to cut tiny cursive letters and set names, biographical details, mottos, historical references, and sentiments within an elaborate framework of birds, hearts, urns, and highly stylized foliage. Combining text within such complex filigreed patterns requires meticulous planning and painstaking execution. None, however, are signed or labeled, raising the question: who was this master?

Paper cutting as an art form dates back to the invention of paper by the Chinese in the fourth century and was introduced to America in the eighteenth century by Swiss and German immigrants settling in Pennsylvania. Although made in Philadelphia, this maker’s handiwork is far more intricate than the typical scherenschnitte of the Pennsylvania Germans.2 Perhaps the maker had some exposure to Jewish paper-cutting traditions, as many Jewish cutworks—made as expressions of faith or to mark festive occasions—exhibit a similar level of complexity.

As only one of the cutworks lacks space for a recipient’s name (Fig. 1), they were clearly designed to be presentation pieces. Investigation of the names that appear in these cutworks has revealed that the recipients were either family members of Philadelphia prison reformers who advocated for solitary confinement as a more humane form of punishment, officials and staff members in the two Philadelphia prisons that adopted this system, or visitors to these institutions. Two cutworks (Figs. 6, 8) have a history that suggests they were made by a prisoner. If correct, this helps explain how the practitioner came to have ample time to perfect this craft.

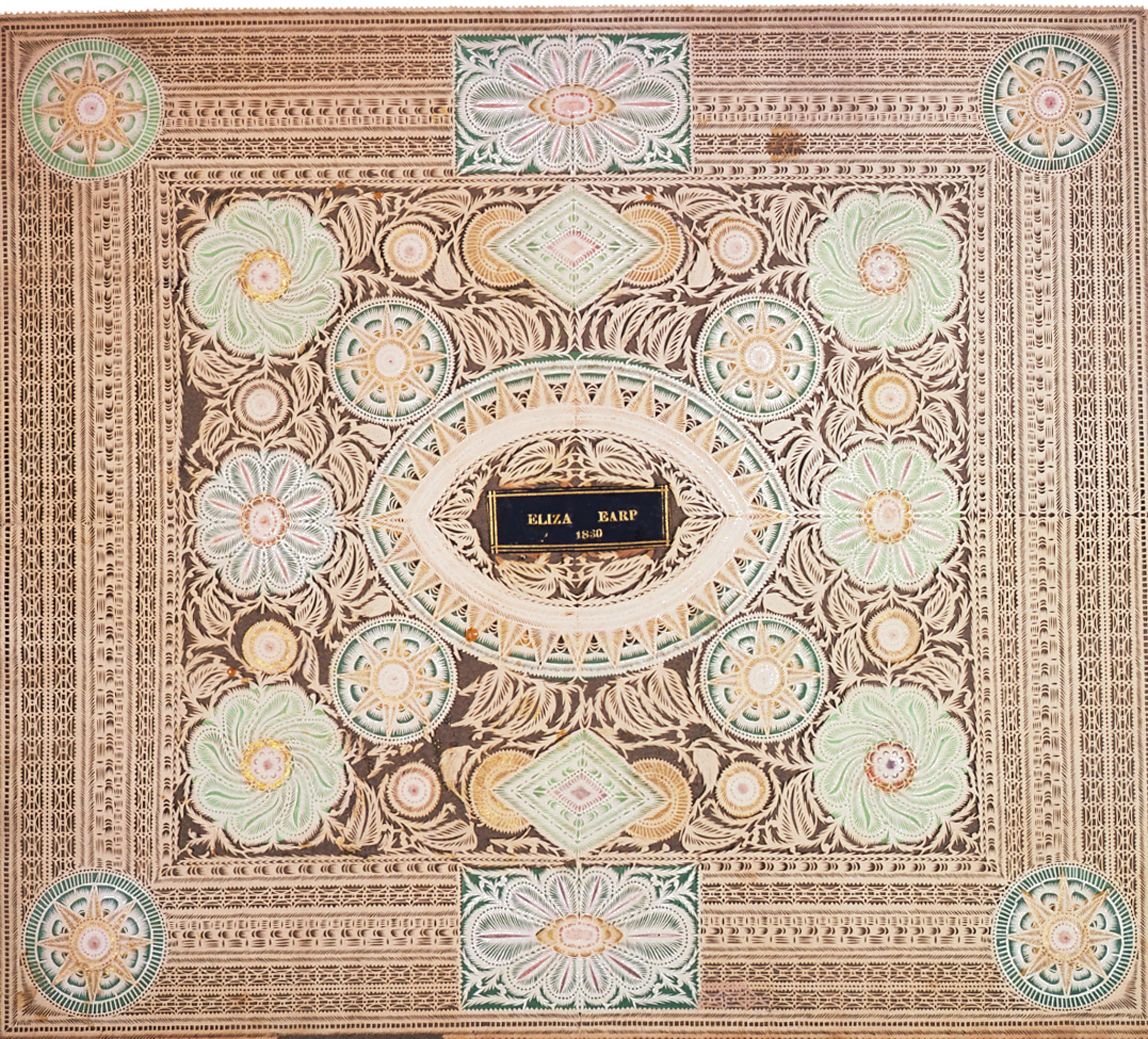

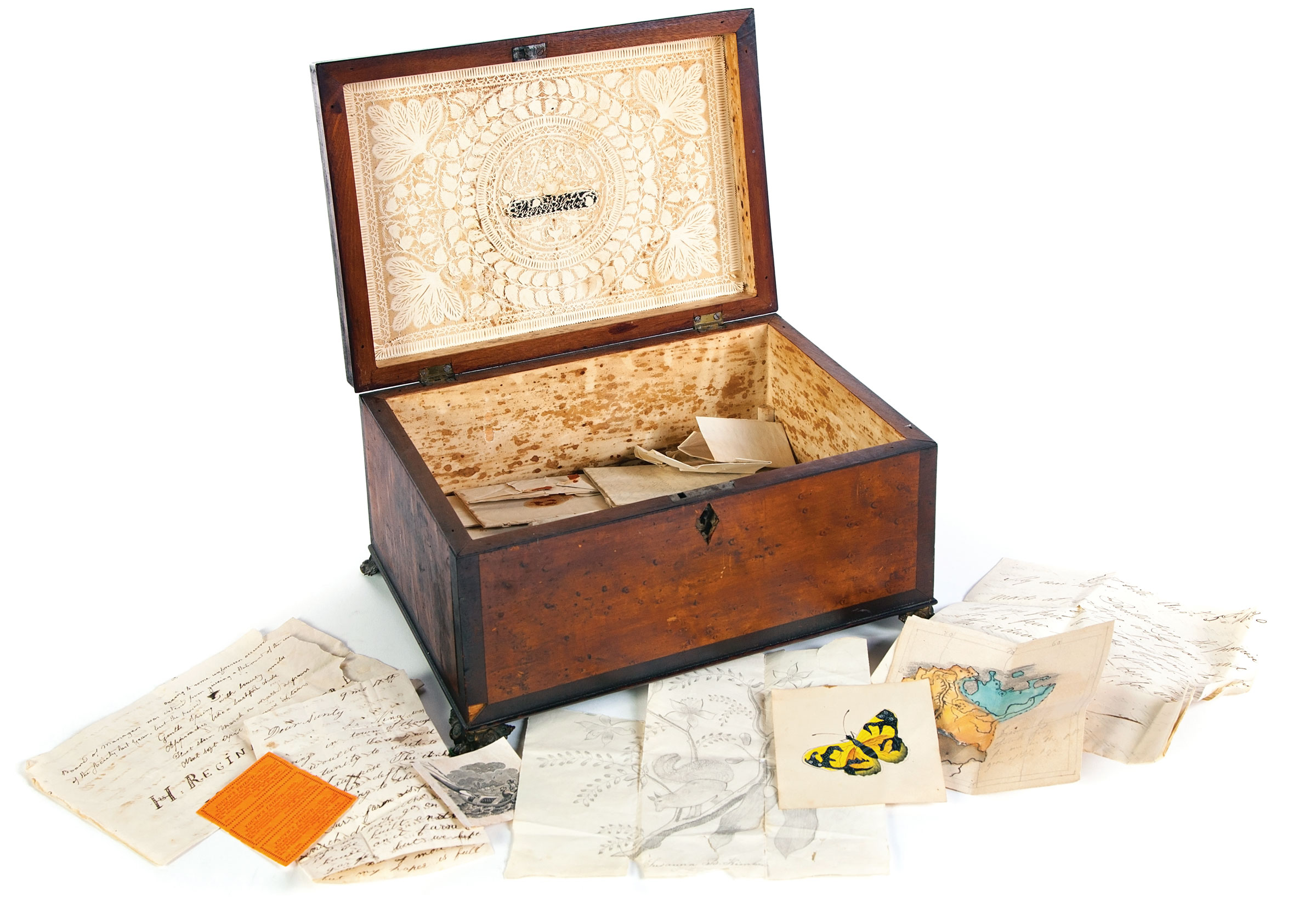

To date, eighteen cutworks can be attributed to this hand, and it seems probable there are more to be found.3 They range in size from seven inches tall by nine inches wide to as large as fifteen by twenty inches. Ten of these cutworks have been highlighted with watercolor and ink before being mounted against colored paper, enhancing their overall effect. Two retain their original frames, while two more have been mounted inside the lids of wooden boxes (Fig. 5).4

Four feature central space for an inscription or label. One has the recipient’s name inscribed in ink directly on the paper support (Fig. 8), while another (Fig. 6) has an embossed label that names the recipient (possibly applied at a later date and obscuring an inscription underneath). A third (not illustrated) features a similar embossed label with “A.J.C.F.” in capital block letters, indicating someone’s initials or an acronym for an organization.5 The fourth has been left blank (Fig. 2). In nine other examples, the maker incorporated the recipient’s name in cut cursive script as part of the overall design, while another in the form of a valentine (not illustrated) carries the initials “M. J.”6

The board of inspectors, which supervised the staff and approved funding at the two prisons, comprised strong advocates of solitary confinement. They considered it the most humane and effective form of rehabilitation and encouraged inmates so confined to pursue individual crafts.11 Thus the idea that an inmate could have made these cutworks is wholly feasible. If the maker did, indeed, have a criminal past, this would also help explain why his work never received the kind of reception it should have in his lifetime.

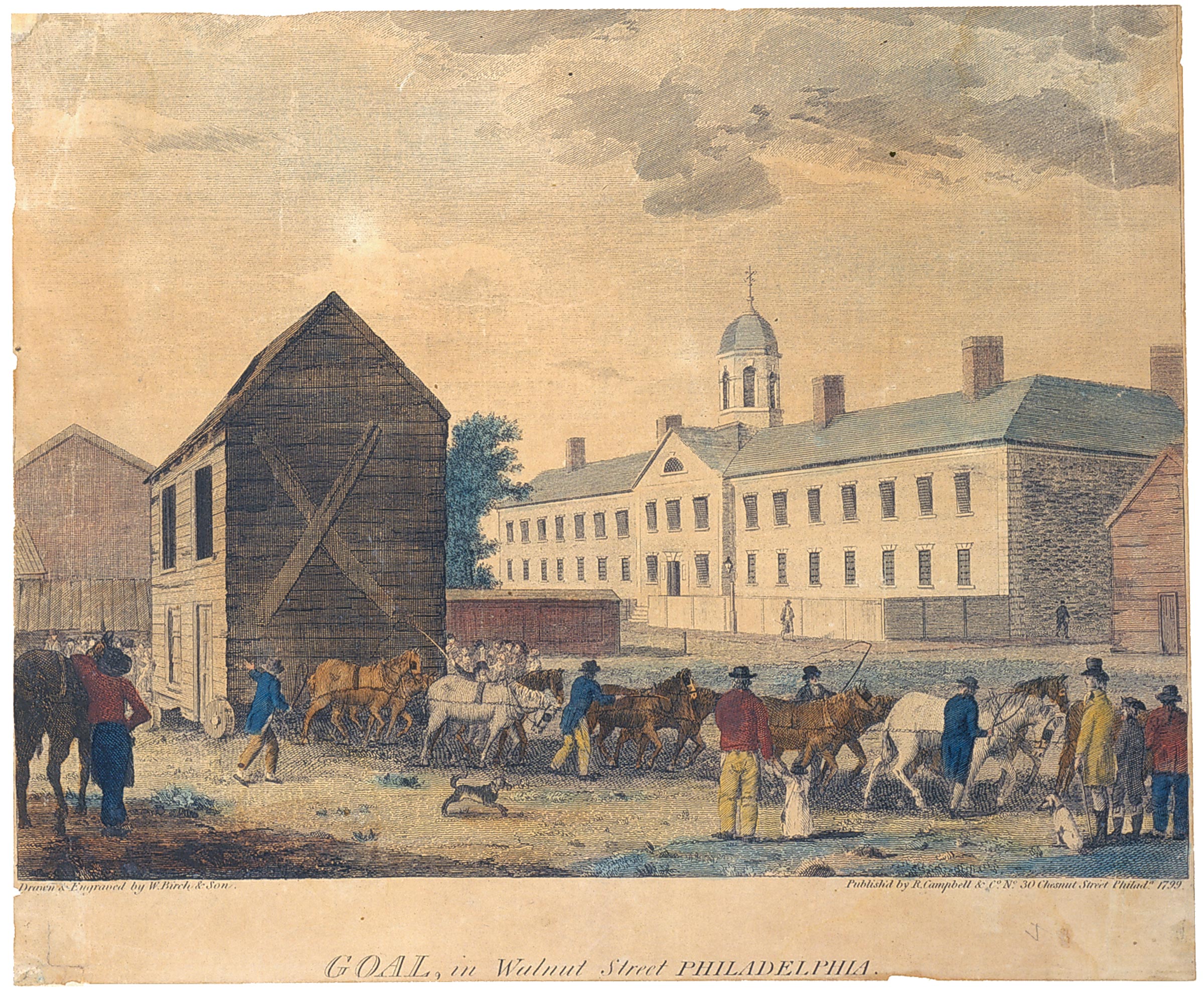

The second clue is the inscription on the back of a cutwork for Hannah Thorn Johns (Fig. 8). It states: “Design cut out of ordinary brown paper folded in four. Cut with a knife by employee of William Johns while in prison for debt. Presented to Hannah Johns—name printed by her son. Early 19th Century. Preserved in glass by her great-granddaughter Emma Buckman.” Hannah (1797–1854) was the wife of William Johns (1791–1860). The provenance of this piece, as stated, is solid, having passed by direct descent to the Johnses’ great-granddaughter Emma Buckman (1880–1968). The reference to the maker being an employee of William Johns is, however, challenging. Beginning in 1817, debtors were traditionally incarcerated in nearby Arch Street Prison. Built in 1804, this prison was initially designed to address the issue of overcrowding at Walnut Street Prison but instead ended up housing non-criminal prisoners such as debtors or those awaiting sentencing.12

Johns was a painter and glazier, and there are no records of him employing inmates at either Arch or Walnut Street prisons. However, he was a Quaker and a member of the Provident Society for Employing the Poor, established in Philadelphia in 1824, and in 1831, he served as an officer on the board alongside Eliza Earp’s brother-in-law Robert Earp (1789–1848). As a member of such a tight-knit community of philanthropists, he would have had contact with staff and inmates at the Walnut Street facility. This may have been one of the “other things” made by the convict mentioned in the letter attached to the Earp cutwork. This would fit with the work’s somewhat garbled history. Describing the maker as a debtor rather than a felon likely made it more appealing as a family heirloom.

One of the more pristine examples from the body of work is that of John Andrew Shulze (1774–1852), who served as governor of Pennsylvania from 1823 until 1829 (Fig. 9). Given the governor’s known propensity to grant pardons, it makes perfect sense that an inmate at Walnut Street Prison would include the words “Be Merciful” in this cutwork.13 It may have been a bid for freedom.

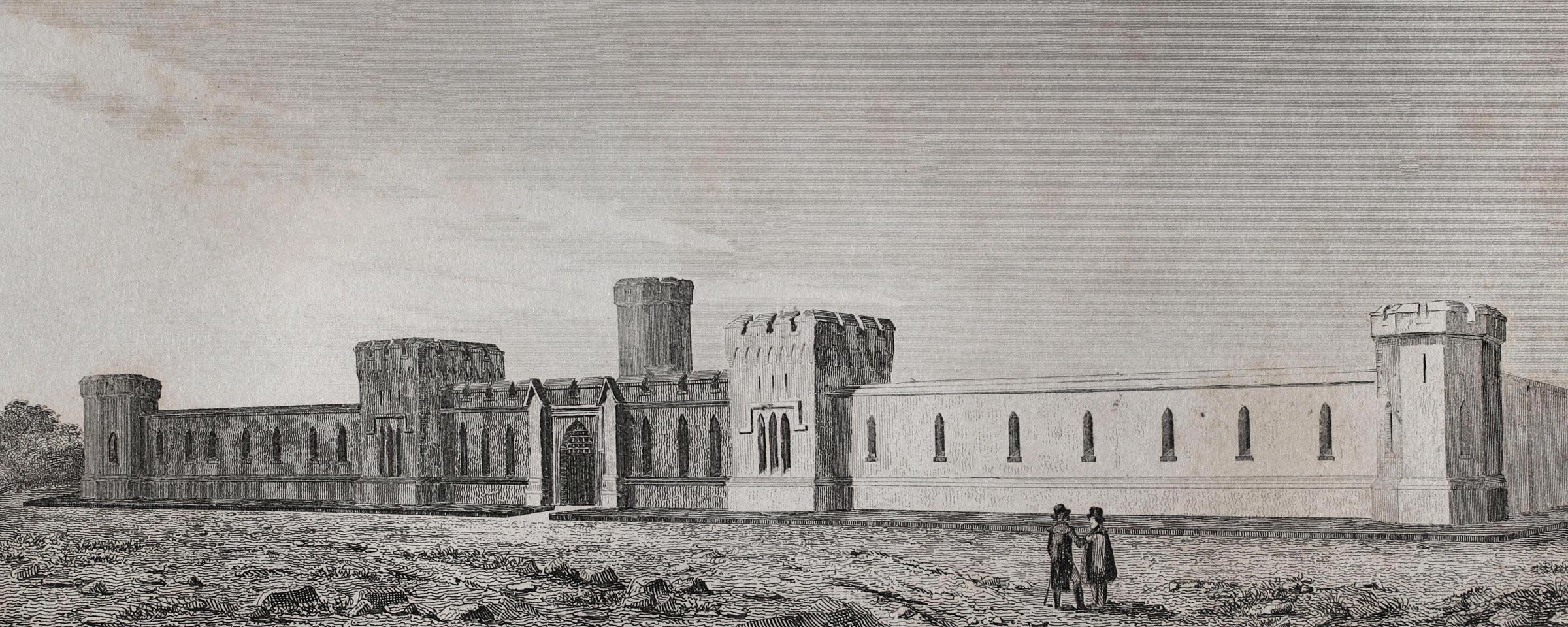

Philadelphia prison records reveal three more recipients who could have had contact with this maker at Eastern State Penitentiary, two who were staff members and another who was the wife of a lawyer that represented the warden. With its system of solitary confinement, Eastern State was conceived as the world’s first true penitentiary in that its aims were rehabilitative instead of strictly punitive (Fig. 12).18 Rather than using physical punishment, such as flogging, the founders hoped the terror of isolation would be enough to deter inmates from becoming repeat offenders. Prisoners were separated by thick stone walls laid out in a radial floor plan of seven one-story blocks that made conversation between cells impossible. Skylights provided the only source of light. Inmates were forbidden to have contact with family or friends or to hear of news or events outside the prison. Each day, inmates were allowed one hour of solitary outdoor exercise, but even this brief respite was frequently shortened in practice. Instead of being referred to by name, inmates were addressed by a number assigned upon arrival and were required to wear hoods when outside their cells.19

Many inmates had resorted to crime simply to survive. Now, for the first time, they were enjoying three square meals a day, receiving clothing and medical attention, and being taught to read and write. They also acquired marketable skills in trades that were suited to the narrow confines of the cells. Their labor was intended both to aid in their rehabilitation and help offset the costs of their upkeep. Trades practiced at Eastern State Penitentiary included “shoemaking, spinning, weaving, dyeing, yarn dressing, blacksmithing, carpentry, sewing, wheelwrighting, wood turning, brush making, and tin working.”20 Being allowed to labor was a privilege, and if prison staff observed deviant behavior they would often withdraw it. The prison offered limited opportunities to earn from one’s assigned occupation.21 Still, making these cutworks might have been more than a therapeutic pursuit; it may have provided a means to earn some money before release or to support family on the outside.

Two cutworks of similar design feature the names of Eastern State Penitentiary staff members and their spouses set within an octagon and flanked by orbs at each corner (Figs. 13, 14). John Blundin (1810–1882) worked there as a watchman from 1829 until December 1830.22 In August 1834, he returned to serve as a watchman, before being promoted to overseer in November 1835. In this position, he served as an instructor of handicrafts undertaken inside inmates’ cells. Blundin and his wife, Elizabeth Lott (c. 1809–aft. 1850), were married in Philadelphia on December 3, 1835, a union commemorated in their cutwork.23 The maker’s confinement may also explain the otherwise puzzling inclusion of the word “Liberty” between the two names (Fig. 13).24 Curtis Clayton (1798–1890) was the other Eastern State Penitentiary staff member who received a cutwork (Fig. 14). His is mounted in a mahogany block corner frame that echoes the design of the cutwork and appears to be its original housing.25 This piece, which names Clayton and his wife, Margaret, is the only one to include a religious sentiment: “In God is our Trust.”

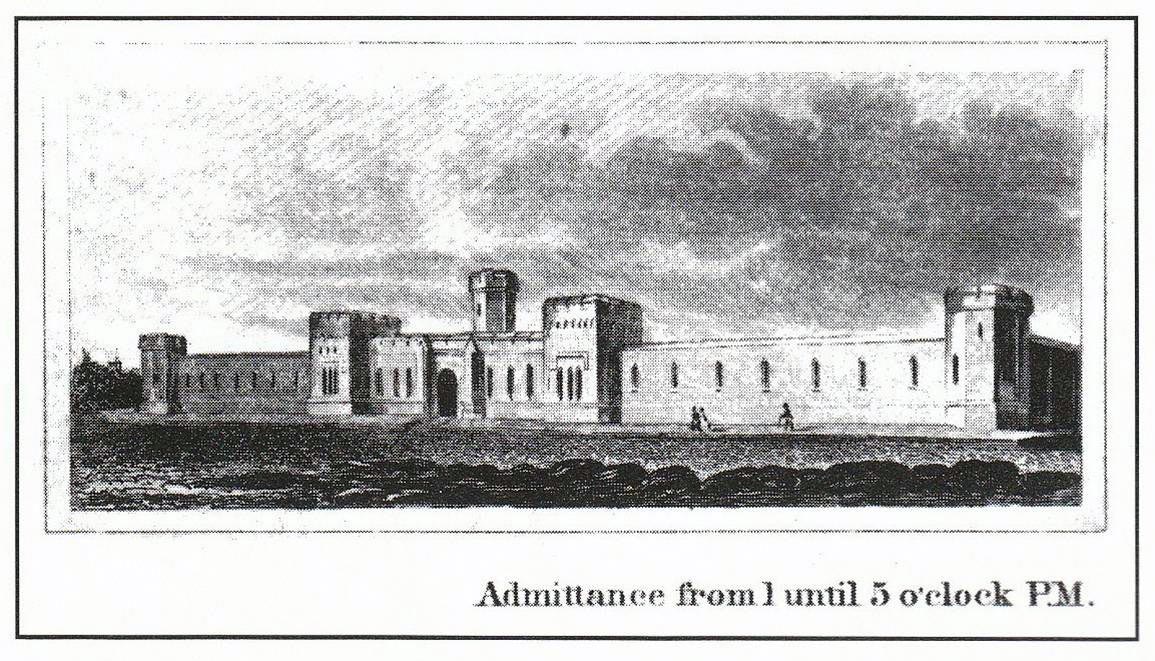

Other recipients of cutworks, with no clear connection to the prison, may have encountered the maker and his work as visitors to Eastern State Penitentiary. Members of the public could purchase admission tickets (Fig. 16) and may have commissioned cutworks while touring the facility.29

Prison records, albeit incomplete, have yielded a possible maker whose history is consistent with the narrative laid out in the letter connected to the Earp cutwork: Abraham Eldred, whose numerous aliases included Abraham Eldrid, John Brown, John White, and Benjamin Eldrid. He was born about 1794 on Long Island, New York, and was a weaver before becoming a thief, a forger, and the owner of a groggery in Philadelphia. Given his trade, he could have had the dexterity to undertake intricate cutwork. His place of birth, age, and history of incarceration overlap with the history given by Earp’s great-granddaughter.33

In July 1828, Eldred was sent to Walnut Street Prison to serve a seven-year sentence on charges of larceny. This is where Earp’s 1830 cutwork was executed. At the trial, his conduct prior to the crime was described as fair and not suspicious.34 Released from Walnut Street Prison in April 1835, he would have been at liberty to undertake the two oversized Baker cutworks.35 Just one year later, on April 30, 1836, Eldred was incarcerated again, this time at Eastern State Penitentiary, serving six years hard labor for larceny.36 This would have placed him in direct contact with Warden Wood, who had previously served as an inspector at Walnut Street and may have been acquainted with Eldred there. At Eastern State, Eldred would have had contact with the overseers Blundin and Clayton and possibly Williams, the warden’s legal advisor.

The Eastern State Penitentiary admission record book describes him as “Abraham Eldred, 42, Long Island, NY, can’t read or write, gets drunk; married; Larcenies 6 years. An old convict mind sometimes slightly impressed with the certainty of death and judgment but hopeless of change. Poverty and want of employment forces him to steal. Has been to Walnut St. prison repeatedly.”37 The maker of these cutworks would not have needed to be literate, despite their textual features. Some of the best engravers of counterfeit American money in this era could not read or write English.38 Such craftsmen required only a prototype to imitate.

Upon his release on April 30, 1842, Eldred’s Eastern State Penitentiary record was amended to read: “he had learned to read in prison, also writing and some arithmetic.”39 At the time of his release, he signed his name in the affidavit book with a decided flourish, “Abraham Elarid.”40 In January 1844, sentenced to four years for forgery, he returned to Eastern State Penitentiary and was assigned prisoner number 1786. The convict reception register noted that he went by the name “John Brown, al[ias] White, formerly No. 591 Abraham Eldred: 50 years, native of N. York, bound to a weaver master who wouldn’t have him, trade weaver, fourth conviction, second one here, parents dead, reads but cannot write, drinks, married, no property, crime forgery, sentenced four years Philadelphia Court, Quarter Sessions, received January 11, 1844, clothing decent.”41

Repeat offenders did not get the same privileges as those entering the prison for the first time, which could explain why no later examples of these cutworks have been found. Eldred served his full sentence and was released in January 1848.42 In March 1850, he was arrested in Baltimore on the charge of passing counterfeit money and sent to the Maryland State Penitentiary to serve a fifteen-year sentence.43 He died there on August 26, 1854. According to his death notice, Eldred was sixty years old at the time of his passing. He had previously claimed he kept a groggery in Philadelphia and took up circulating counterfeit money in the winter of 1850 when his groggery did not pay.44

Whether Eldred or another inmate made them, the unique designs and superlative quality of these Philadelphia cutworks constitute a remarkable legacy that clearly warrants further study.

Addendum

Since the initial online publication in 2021 of “Tributes in Paper from the City of Brotherly Love,” Child has discovered five more cutworks attributable to the maker discussed in the essay, bringing the current number of cutworks that can be attributed to this hand to twenty-three. This addendum discusses these new examples, expanding on and supporting her original research.

Halloway was the granddaughter of John S. Halloway, also spelled Holloway, (1805–1870), who served as a clerk to Warden Wood at Eastern State Penitentiary when it opened in 1829. Given her family history, it is not surprising that she inherited a cache of these cutworks. Her grandfather’s name appears frequently in the prison affidavit book, which records the entry of new prisoners, and in the warden’s daily journals.54 He later went on to serve as the warden there, from 1850 to 1854 and again from 1856 until his death in 1870. Harriette’s father, Henry Rice Halloway (1839–1911), also served as a clerk at the prison, in 1865, before relocating to Plainfield, New Jersey.

Additional evidence that Eldred was, indeed, the maker of this remarkable body of cutworks has come to light. In April 1836, items stolen by Eldred and his two accomplices that the authorities had confiscated were to be sold at public auction. The confiscated goods included a number of hams and shoulders, remnants of printed calicoes, flannels, apparel, pistols, hardware, bags and sacks, wagon covers, measures, valises, and a variety of other articles.55 This is wholly consistent with the profile of the maker of Earp’s cutwork (Fig. 6), described in the family letter as a “leader of a gang that broke into houses.”

A closer examination of the prison records explains how Eldred likely came to make these tributes in paper for the prison staff and their families. In his report to the prison’s board of inspectors, physician Franklin Bache (1792–1864), great-grandson of Benjamin Franklin, noted that convict 591 (Eldred) had become dangerously ill with typhus (often called jail fever), contracted no doubt in Arch Street Prison while awaiting sentencing.56 It is plausible that he received guidance while in the infirmary recovering, which would explain how Eldred, then illiterate, was able to correctly spell the inscriptions in his cutworks. Furthermore, the inclusion of the Latin expression libertate nihil dulcius suggests Dr. Bache, probably the sole individual versed in Latin on prison staff, may have encouraged Eldred to pursue his craft (Fig. 20).

However beautifully these cutworks may have been executed, they obviously did little to secure Eldred a legitimate livelihood or dissuade him from pursuing a dissolute life. How poignant to think that a person so artistically gifted is only now getting the recognition he so richly deserved.

Acknowledgments

About the Author

1 Lisa Minardi, correspondence with author.

2 Sandra Gilpin, “Scherenschnitte and Fraktur,” Pennsylvania Folklife 37, no. 4 (Summer, 1988): 190–92. Cutworks are referred to as “cutouts” or “papercuts.”

3 Of the eighteen cutworks, only fourteen are illustrated in this essay. Eight works by this hand were first identified by Lisa Minardi in her book Drawn with Spirit: Pennsylvania German Fraktur from the Joan and Victor Johnson Collection (New Haven: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2015), 335.

4 One of these two boxes, not illustrated in this essay, has been identified as a sewing box. It is in the John and Carolyn Grossman Collection, Col. 838, box 250, at the Winterthur Library.

5 Ibid. This cutwork, featuring the “A.J.C.F.” label, is the sewing box example at the Winterthur.

6 Important Frakturs, Embroidered Pictures, Theorem Paintings and Cutwork Pictures from the Collection of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch (New York: Sotheby Parke Bernet, 1974), 24, lot 51. This recipient has yet to be identified. The current whereabouts of this cutwork are unknown.

7 According to Eastern State Penitentiary Historic Site’s website, the new prison was “known for its grand architecture and strict discipline” and was “the world’s first true penitentiary, a prison designed to inspire penitence, or true regret, in the hearts of prisoners. The building itself was an architectural wonder; it had running water and central heat before the White House and attracted visitors from around the globe.” “About Eastern State,” Eastern State Penitentiary Historic Site, accessed October 10, 2022, eastern state.org.

8 “Annual Meeting of the German Society,” Poulson’s American Daily Advertiser (Philadelphia), December 29, 1824.

9 “Married,” Philadelphia Gazette, December 9, 1815. William Pidgeon is listed in city directories as deputy keeper at Walnut Street Prison in 1825, 1828, 1829, 1830, and 1831. See, for example, DeSilver’s Philadelphia Directory and Stranger’s Guide (Philadelphia: 1830), 152. He had left the prison by 1833, when he is listed in DeSilver’s as senior cordwainer (shoemaker), 751.

10 Norman Bruce Johnston, Kenneth Finkel, and Jeffrey A. Cohen, Eastern State Penitentiary: Crucible of Good Intentions (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2000), 26–29.

11 Jacqueline Thibaut, “To Pave the Way to Penitence: Prisoners and Discipline at the Eastern State Penitentiary,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 106, no. 2 (April 1982): 187–222. When space constraints at the Walnut Street Prison limited the number of convicts that could be housed in isolation, prison reformers insisted a new prison was a necessity, which resulted in the unusual design of Eastern State Penitentiary.

12 LeRoy B. DePuy, “The Walnut Street Prison: Pennsylvania’s First Penitentiary,” Pennsylvania History 19, no. 2 (April 1951): 2–16. For contemporaneous accounts of Arch Street Prison, see “A Day in the Arch Street Jail,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 20, 1830; “Chamber of Commerce,” Philadelphia Inquirer, January 19, 1831.

13 See, for example, Governor John Andrew Shulze executive minutes, June 1, 1829, series 9, vol. 9, 6972–73, Executive Minute Books, RG-026-AOSC, Pennsylvania State Archives, Harrisburg (hereafter cited as Executive Minute Books).

14 List of Members, 1814–1828, Philadelphia Monthly Meeting (Pre-Separation and Hicksite, 1682–1957) Records, SW/Ph/P460, Friends Historical Library, Swarthmore College, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania. Ann was the daughter of Caleb Coleson (also spelled Colson) and Sarah Bradway, who married in Salem, New Jersey, in 1812.

15 Judith Scheffler, “‘Wise as serpents and harmless as doves’: The Contributions of the Female Prison Association of Friends in Philadelphia, 1823–1870,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 81, no. 3 (2014): 305. On the back of Coleson’s cutwork are inscribed the dates and place of the First Convention of the Pennsylvania Deaf-Mute Association, held in Harrisburg, August 24–26, 1881. There is no record of Coleson being so afflicted.

16 For more on this society, see “Female Society of Philadelphia for the Relief and Employment of the Poor Records,” Haverford College, TriCollege Libraries Digital Collections, Female Society of Philadelphia for the Relief and Employment of the Poor Records.

17 Like many other recipients of these cutworks, Louisa Warren was affiliated with the First Presbyterian Church. Marriage record for Louisa D. Warren to Mr. Joseph Adam, September 7, 1833, Pennsylvania and New Jersey Church and Town Records, 1669–2013, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, retrieved from Ancestry.com (hereafter Church and Town Records).

18 Eastern State Penitentiary was in continuous operation until 1971 and is now a popular tourist attraction.

19 Johnston, Finkel, and Cohen, Eastern State Penitentiary, 47–49.

20 Negley K. Teeters, “The Early Days of the Eastern State Penitentiary at Philadelphia,” Pennsylvania History 16, no. 4 (October, 1949): 272.

21 According to prison records from 1831, “15 prisoners employed at winding bobbins and spooling earned 25 cents a day, a sum calculated to meet the charges against them.” Minutes of the board of inspectors of Eastern State Penitentiary, September 17, 1831, Eastern State Penitentiary Prison Administration Records, RG-015-GG, Pennsylvania State Archives, Harrisburg (hereafter cited as ESP Records).

22 Also spelled Blunden, Blandin, Blanden, and Blundell. The earliest reference to a John Blundin being employed at Eastern State can be found in the state treasurer’s report of April 23, 1829, in which he is listed as receiving $61.81 as a watchman. Treasury Office of Pennsylvania, Report of the State Treasurer, Shewing Receipts and Expenditures at the Treasury of Pennsylvania from the First Day of December, 1830, to the Thirty-First October, 1831, Inclusive (Harrisburg, PA: Henry Welsch, 1831), 32. Warden Wood also mentions Blundin in the minutes of the board of inspectors for November 7, 1835: “On the 7th Robert Cain left his station as an overseer. On the 12th I placed John Blundin in his place and appointed Samuel Adair a watchman in the place of John Blundin.” ESP Records.

23 Marriage record for John Blundin and Elizabeth Lott, December 3, 1835, Church and Town Records. The couple married at St. George’s United Methodist Church in Philadelphia.

24 Loss of his own “liberty,” rather than theirs, may have been foremost in his thoughts.

25 This frame is not shown in Figure 14, but an identical frame can be seen in Figure 15. The frame on the cutwork for Curtis and Margaret Clayton is, however, illustrated in Minardi, Drawn with Spirit, 232–33, fig. 189.

26 Wood records in his journal for December 17, 1834: “Went into the city early and saw William Memdill and H. J. Williams who went with me as council [sic] to the committee of investigations.” Warden’s daily journals, ESP Records.

27 For details of the scandal and aftermath, see Thomas B. McElwee, A Concise History of the Eastern State Penitentiary of Pennsylvania: Together with a Detailed Summary of the Proceedings of the Committee Appointed by the Legislature, December 6th, 1834 (Philadelphia: Neall & Massey, 1835), 7–107.

28 Pennsylvania Senate, “Report Relative to the Eastern Penitentiary,” Journal of the Senate of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania which Commenced at Harrisburg on the Second Day of December, 1834, and of the Independence of the United States the Fifty-Ninth, vol. 2 (Harrisburg, PA: Welch and Patterson, 1835), 543.

29 “Visitors with a ticket from Mr. Bevan were kindly received, politely treated and shown all that visitors with tickets are usually shown. During their stay (of about 3 hours).” Minutes of the board of inspectors, October 3, 1835, ESP Records.

30 The Chalkley Baker cutwork sold at Cowan’s Auctions, June 19, 2015, lot 4, with Baker identified as the maker. For Baker’s claims that the Declaration of Independence had been written in his tavern, see Public Ledger (Philadelphia), October 7, 1837. Thomas Jefferson actually penned this document at the home of Mr. Graff on Market Street. Daily American Organ (Washington, DC), January 13, 1855.

31 “A Good Sign,” United States Gazette (Philadelphia), July 25, 1835.

32 “Junior Artillerists,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 19, 1834.

33 Abraham Eldred was probably a black sheep of the Eldert family, one of the first families of Long Island. Unfortunately, there are too many Abraham Eldreds to know which branch of family he may have descended from to confidently identify him.

34 “Commonwealth vs. Abraham Eldred and Nathaniel Strong,” Register of Pennsylvania: Devoted to the Preservation of Facts and Documents, and Every Other Kind of Useful Information Respecting the State of Pennsylvania, vol. II, no. 12 (Philadelphia: W.F. Geddes, 1829), 192. Only three prison sentence docket books for Walnut Street Prison remain in possession of the city of Philadelphia, but they are in such fragile condition that it has not been possible to access them.

35 “April 9, 1835: Governor Wolfe remitted sentence passed upon Abraham Eldred who was convicted of the crime of larceny and sentenced by the Court of Quarter Sessions in said County, October 8, 1828 to undergo imprisonment at hard labor at the Penitentiary of the City of Philadelphia pay a fine of one cent with costs of prosecution & c.” Executive Minute Books, series 9, vol. 10.

36 “Abraham Eldred to serve sentence on two convictions for larceny 3 years each.” Warden’s daily journals, ESP Records.

37 Eastern State Penitentiary admissions book A, 1830–39, Mss.365.P381p, American Philosophical Society Library, Philadelphia (hereafter cited as Admissions Book A). These records, compiled by a moral instructor at Eastern State Penitentiary, include information on approximately half of the prison population during the 1830s.

38 “Benjamin Moses,” Sentinel and Witness (Middletown, CT), July 16, 1828.

39 Admissions Book A.

40 Convict Affidavit Books, Vol.1, 1835–56, ESP Records.

41 Convict Reception Registers 1842–1929, ESP Records. The warden’s daily journals for January 11, 1844, record: “Received no. 1786 John Brown crime forgery, sentence four years.” ESP Records.

42 “Jan. 10 1848: discharged No. 1786 Abraham Eldred in good bodily health, no complaints to make.” Warden’s Daily Journals, ESP Records.

43 “From our Baltimore Correspondent,” Daily Union (Washington, DC), March 19, 1850.

44 “Death of an Old Convict,” Washington Sentinel, September 3, 1854.

45 Rather than the wooden knobs found in the center of the corner blocks on the Curtis and Margaret Clayton frame, the Williams frame features black painted dots.

46 The current owner acquired this cutwork in 2006 from Joe Kindig Antiques, York, PA.

47 A reader of this publication, Kathy Gleisieur, kindly brought this cutwork to the attention of the author.

48 A “Miss Hall of Wilmington Delaware” signed the Eastern State Penitentiary visitor’s log book on October 26, 1836. At that time, she was still living in the Wilmington household of her father, Willard Hall (1780–1875). In 1840, Lucinda married Robert Robinson Porter (1811–1876), a native of Wilmington who also had ties to Philadelphia. During the course of Porter’s medical training at the University of Pennsylvania, he may well have met Eldred. The topic of his 1833 thesis is recorded as cholera epidemics, an ongoing problem at such city institutions as Walnut Street Prison, where Eldred was incarcerated from 1828 until April 1835. At the time of Lucinda’s visit to Eastern State Penitentiary, Dr. Porter was the attendant physician at the nearby Friends’ Asylum for the Insane.

49 Eastern State Penitentiary registers of visitors, 1829–54, ESP Records. Samuel L. Shober and his wife’s prison visit occurred on May 9, 1836.

50 The inscription was incorrectly identified as “Eliza Page” when presented at auction, October 23, 2022, lot 534, New England Auctions, Branford, CT.

51 Tage’s business was located at 17 South Street, which was less than a mile from the prison. American Sentinel (Philadelphia), October 8, 1830.

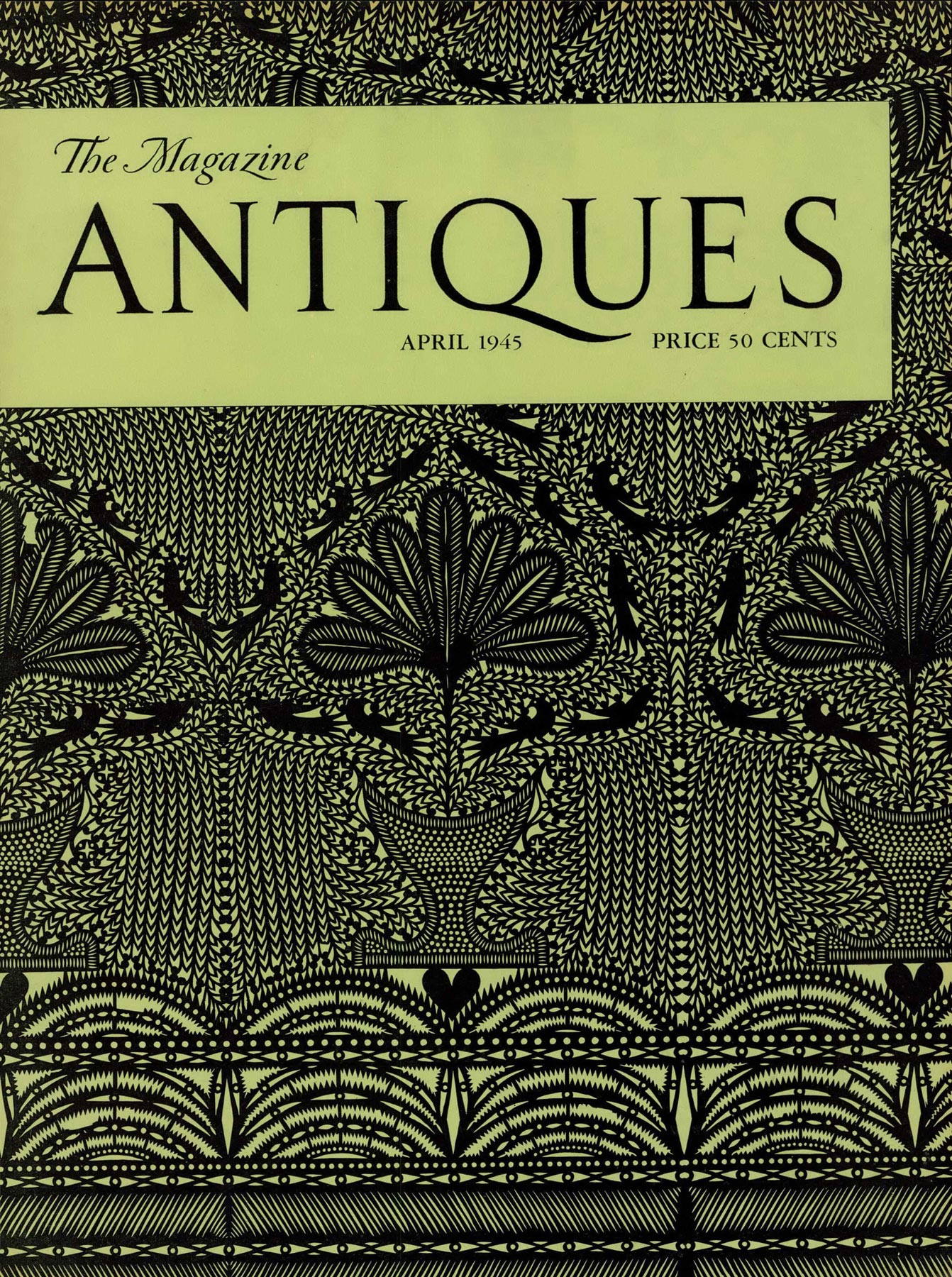

52 This example is not illustrated in full in The Magazine Antiques article and its current whereabouts are unknown.

53 Alice Winchester, “The Cover,”The Magazine Antiques, April 1945, 213.

54 Convict affidavit books, vol. 1, 1835–56, ESP Records. See also Teeters, “Early Days of the Eastern State Penitentiary,” 276.

55 American Sentinel, April 16, 1836. Accomplice Samuel Wilson, alias Babcock, was also committed for three years to Eastern State Penitentiary and assigned convict number 592. He died in the prison at the age of forty-nine on April 11, 1837, after a prolonged period of poor health. What happened to his other accomplice, whose name is given only as Kitchen, is not known.

56 Arch Street Prison often held prisoners like Eldred while they awaited sentencing. Minutes of the board of inspectors, May 1836, ESP Records. From 1821 to 1836 Franklin Bache served as the physician at Walnut Street prison and from 1829 to October 4, 1836 at Eastern State Penitentiary. As early as 1820 Bache was serving as director for the Pennsylvania Institute for the Deaf and Dumb alongside Samuel R. Wood. The Eastern State Penitentiary visitor’s logbook also cites pupils from the institution visiting the prison on June 8, 1838. This may be a clue as to how the cutwork for Ann Coleson came to later bear the label “Deaf-Mute” (Fig. 10).