A Sign of the Times:

Stephen St. John’s Canal Hotel Sign

The Canal Hotel sign is a two-sided roadside advertisement for an establishment Stephen St. John opened in his home, around 1826, in a town in Orange County, New York, then known as Deerpark and subsequently as Port Jervis.1 The sign (Figs. 1a, 1b) is an important piece of American folk art, not only for its aesthetic qualities but also because it is a valuable primary source for the history of the tristate region of New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, documenting a transformative period in the development of transportation and industry in America.

The Canal Hotel and earlier structures on its site were situated along what has been called the oldest continuously used road in America. Built by the Dutch before 1664, it ran from Kingston, New York, a little more than seventy miles northeast of Port Jervis, to the Pahaquarry Copper Mines, in Hardwick Township, New Jersey. Called the Old Mine Road, or the Hundred-Mile Road, it followed the paths of ancient Native American trails. The first known Dutch settlement along this road was near Port Jervis.

The first structure on the site of the Canal Hotel was a trading post built by the Dutch settler Frederick Hayne (1732–1807). Hayne arrived in the Delaware Valley sometime before 1755 and erected the original structure between 1755 and 1760. It likely served as a place to trade with nearby Native Americans, as well as a place of protection. Firsthand accounts collected by a nineteenth-century author describe the original building: “The old fort was one and a half stories in height—the first half story being solidly constructed of stone . . . with alternate layers of logs, lapping and overlapping each other, the crevices being filled with mud and improvised mortar, until the desired height was reached.”2

Frederick Hayne married Catherine Decker (1738–1807), and their daughter Margaret (1759–1840) married Wilhelmus Westfall (1754–1806) around 1778–1780. Catherine’s brother Lieutenant Martinus Decker (1733–1802) came to live on the Hayne-Westfall-Decker farm in 1775 while supporting the Patriots in their rebellion against Great Britain. His son Martinus, Jr. and the brothers Simon and Wilhelmus Westfall were also involved in the war effort, and during the Revolution, the stone house became known as “Fort Decker.” The region was subject to attacks by the famed Mohawk military leader and diplomat Joseph Brant, a.k.a. Thayendanegea (1743–1807), and his contingent comprised of fellow Mohawks and colonial Loyalists. After earlier raids in the surrounding valleys, Brant’s forces attacked and burned Fort Decker on July 20, 1779, and the building was destroyed. It wasn’t until 1793 that, as later recounted, “the debris was removed, the work of rebuilding commenced. The foundations were found to have received little or no injury and a portion of the walls remained intact.”3 Reconstruction extended the stonework to include a second story.4

When Martinus Decker died in 1802, his assets included the stone house, a barn, and two hundred and twenty acres of land. His son Richard (1767–1851) inherited the property and lived there until 1815, when he sold it to John Kent, the first non-family member to assume ownership. Kent, in turn, sold it to Stephen St. John and his business partner Benjamin Dodge for $5,000 in 1819. Soon after, St. John bought Dodge’s half interest in the property, and he and his wife, Abigail, moved into the house, where all of their children were born.

After the Revolution, efforts to create a new, unified nation were impeded by critical transportation needs. In the late eighteenth century, most of America’s population was clustered on the Atlantic coast, and traveling any distance was slow, difficult, and expensive. Roads were mostly footpaths and wagon trails that were locally and privately built and often poorly maintained. Because of the undeveloped state of the new country’s roads and waterways, it was difficult to move agricultural products from the sparsely populated interior of the country to urban markets in coastal cities. America lacked the integrated transportation systems necessary for unifying the country and crucial for its development as an autonomous nation.

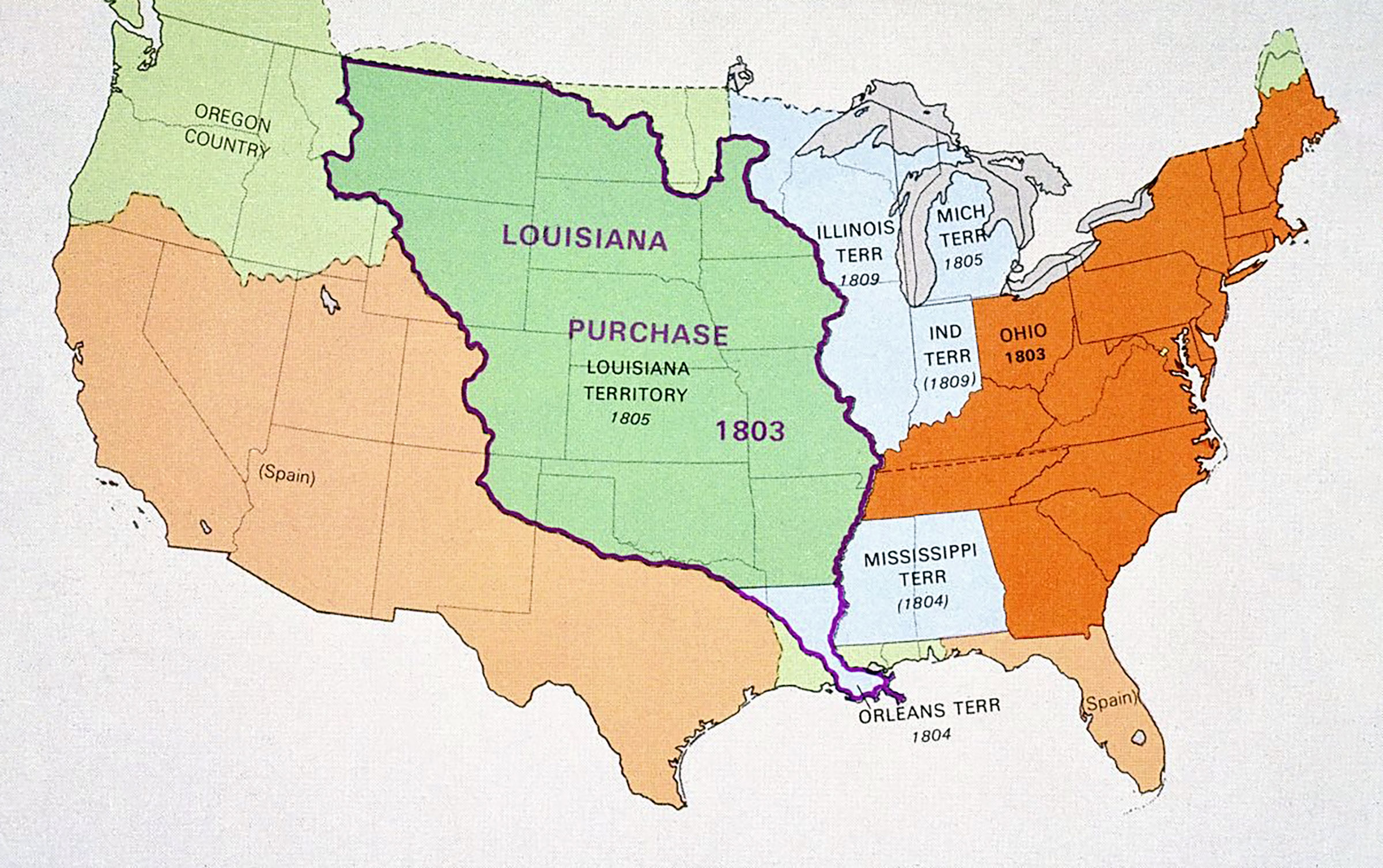

In 1803, the Louisiana Purchase more than doubled the size of America, beginning a process of expansion toward the west and, ultimately, the Pacific coast (Fig. 2). Albert Gallatin (1761–1849), Secretary of the Treasury from 1801 to 1815, who had supported and secured the financing for the purchase, soon began calling for federal support to improve roads—to foster westward expansion, help get produce to markets, and unify the developing nation.

In 1807, the first trial of Robert Fulton’s steamship, the Clermont, ran on the Hudson River. Because steamboats could easily travel upstream as well as down, they would soon transform the use of American rivers and become the dominant engine of inland water transportation. In 1808, Gallatin gave a prescient “Report on the Subject of Public Roads and Canals” to the U.S. Senate, proposing that the federal government fund the construction of systems of turnpikes and canals, as had been done in Europe: “Good roads and canals, will shorten distances, facilitate commercial and personal intercourse, and unite by a still more intimate community of interests, the most remote quarters of the United States. No other single operation, within the power of government, can more effectually tend to strengthen and perpetuate that union, which secures external independence, domestic peace, and internal liberty.”5

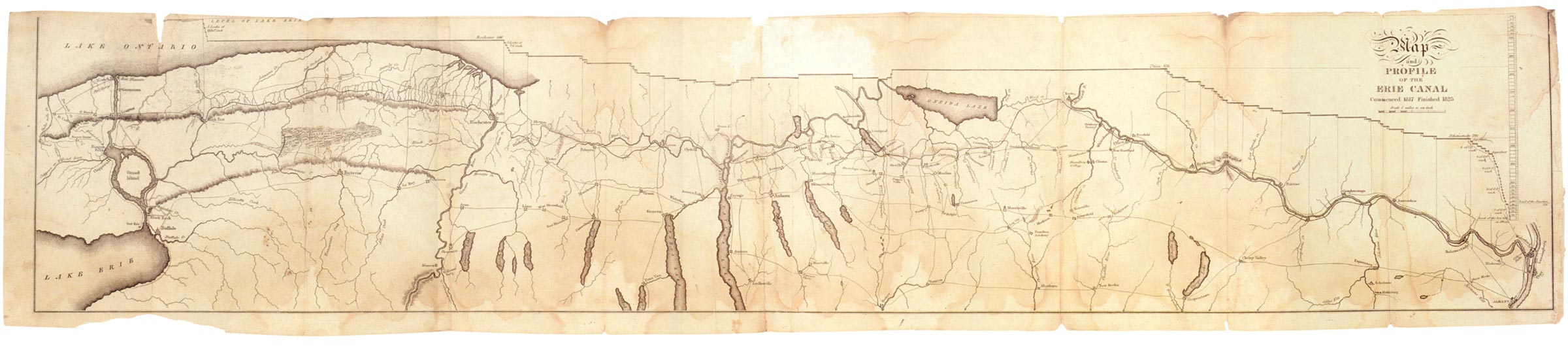

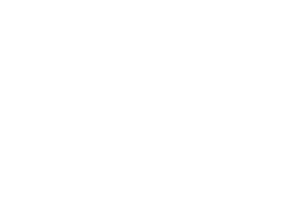

Despite opposition from anti-Federalists, who were against expanding the government’s power, work was begun on the first federally funded national turnpike in 1811. While Gallatin’s proposal for a canal system was deemed too expensive, it did inspire later, state-financed endeavors to facilitate inland waterway navigation, most notably the Erie Canal. Built between 1817 and 1825, the Erie Canal extended from Albany to Buffalo and, via the Hudson River, connected New York City, the country’s busiest port, to the western interior (Fig. 3). It lowered the cost of transporting goods and created reciprocal markets: agricultural products from the interior reached the cities, and manufactured goods from cities were purchased in rural areas. The canal also fostered population growth in places that had been sparsely settled, bringing diversity and greatly increasing the availability of goods and services. Both town and country experienced significant economic growth.

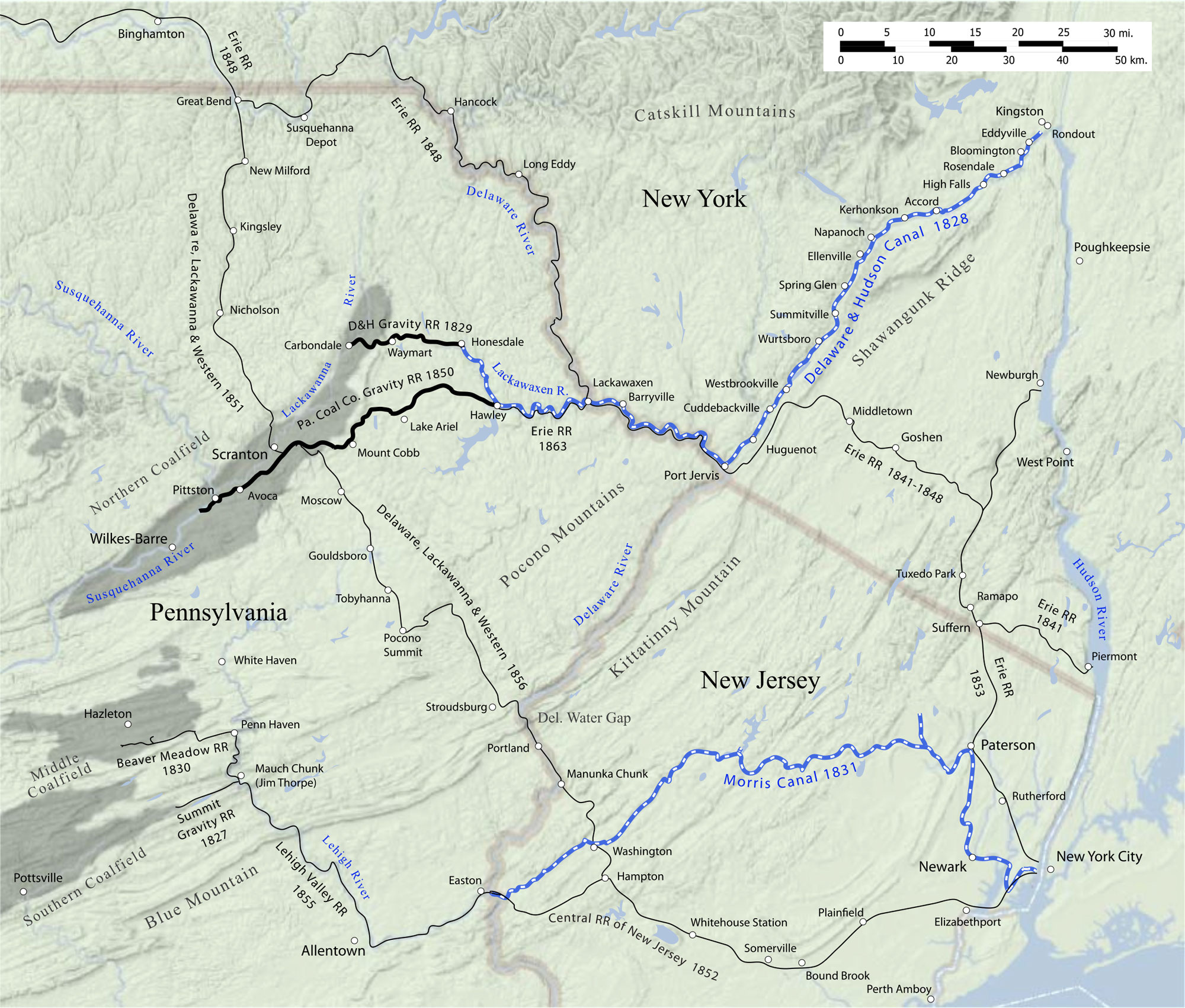

The success of the Erie Canal set off a boom in canal building during the 1820s. Most were financed by states or by a combination of state and private effort, and canal building became a symbol of American accomplishment. Philadelphia brothers William and Maurice Wurts believed that anthracite coal, which had been discovered in northeastern Pennsylvania in 1790, could be a better source of heat than wood, but it was difficult to transport from the coalfields to city markets. Inspired by the completion of the Erie Canal, they proposed building a gravity railroad to bring the hard coal over the Moosic Mountains and then building a canal from Honesdale, Pennsylvania, to Kingston, New York. From there, it could be shipped down the Hudson River to New York City. The route of the canal would roughly follow that of the Old Mine Road. In 1823, the Delaware & Hudson Canal Company (D&H) was incorporated, and in 1825, when the Wurts brothers demonstrated the ability of anthracite coal to heat a Wall Street coffee house, $1 million in stock offerings were sold to investors the same day.

In 1826, construction began on the canal. Stephen St. John’s land was midway along the path of the proposed canal, at the confluence of the Delaware and Neversink Rivers, near the point where Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York meet (Fig. 4).6 The D&H negotiated a right-of-way through St. John’s property in 1826 and purchased a portion of his land. He became the toll collector on this section of the canal and one of D&H’s most important employees. St. John transformed his home into a hotel for the workers and engineers building the Delaware and Hudson Canal. The chief engineer, John B. Jervis, is said to have had a secondary headquarters in the hotel, and he developed a long-lasting friendship with St. John.7 The canal was finished and opened in 1829. The hotel was in operation at least through that date and probably longer, providing lodging for the crews of the barges.

Although it is not known who owned the sign after St. John moved out of the Old Stone House in 1836, it seems likely it remained in the family throughout the nineteenth century. St. John’s granddaughter married Dr. William L. Cuddeback (1854–1931), who initiated efforts to develop the Minisink Valley Historical Society in the former hotel building, and his son Edgar (1882–1944) donated the sign to the society.9 In 1993, the Minisink Valley Historical Society sold the sign to help fund replacement of the structure’s deteriorated roof. It remains in private hands today.10

Unlike most surviving eighteenth- and nineteenth-century American trade signs, the Canal Hotel sign was used by a single owner, pictured a specific house and location, and was hung outside for a limited period, from around 1826 until 1836, when St. John relocated. The sign’s original surface is undoubtedly attributable to this restricted usage and limited exposure to the elements.

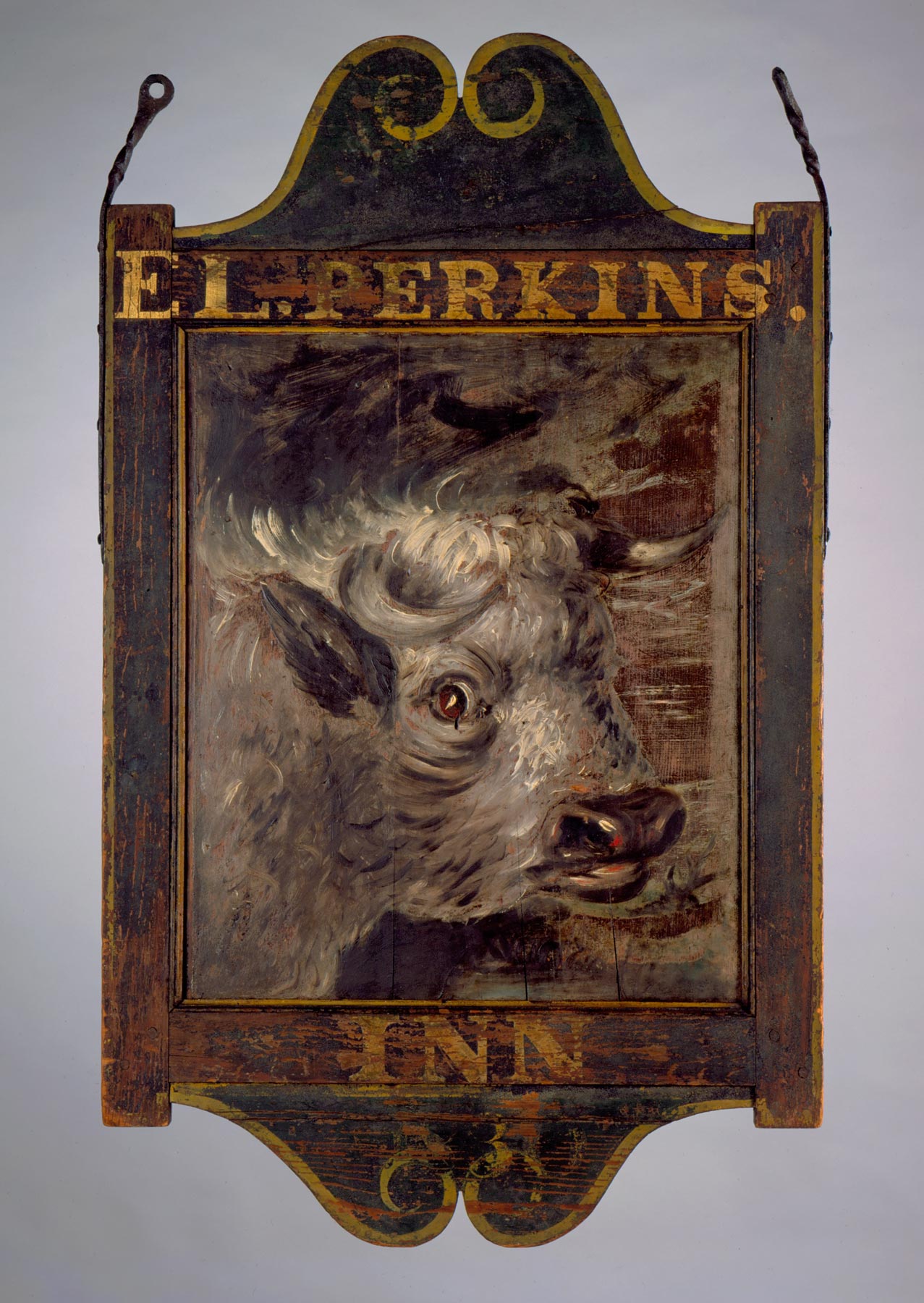

The sign’s imagery is not generic, as is the case with most other early American tavern and inn signs. As Nancy Finlay writes in Lions & Eagles & Bulls: Early American Tavern and Inn Signs from the Connecticut Historical Society, whose title emphasizes the point, “Although the repertory increased somewhat in the early nineteenth-century, most imagery continued to conform to a few defined types: animals, drinking symbols, famous men, and coats of arms” (Figs. 6, 7).11 In addition, most late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century American trade signs were reworked and overpainted by subsequent owners, either by someone who inherited the family business or, if the business was sold, by a new proprietor. Frequently, signs were taken to new locations (Fig. 8).12 “Although American signs rarely matched the elaboration of lavish English examples,” according to Susan P. Schoelwer, “they were similarly composite art forms, uniting distinct crafts of painting, woodworking, carving, and metal-smithing.”13 The Canal Hotel sign’s gilded and paint-decorated central image, which is the same on both sides, is surrounded by a black frame molding, set within an architectural structure with pinned mortise-and-tenon rails and turned posts. Both sides are identical in form and composition, allowing the same image and lettering to be seen by travelers coming from either direction.14

The painted image depicts the stone house, which had a rear addition and front-facing multipaned windows. This is the earliest known likeness of the structure, which has stood on the site since 1793. With flattened perspective, the panel displays a well-rendered tableau of the original hotel situated among fruit trees, farmland, and pastures. The house is set off by a picket fence, and a path leads from it to a canal with a horse-drawn barge. Mount William, a prominent feature of the landscape in Port Jervis, rises behind the canal (Fig. 9). Thick block letters at the bottom of the sign spell out “S, ST JOHN.” Under the “T” of “ST” is the three-link chain of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows (Fig. 10), symbolizing Friendship, Love, and Truth, suggesting the hotel was a meeting place for the fraternity, whose first North American lodge had been founded in 1819. 15

The highly reflective quality of the bold gilt letters on the dark smalt background would have illuminated the sign in the lantern lights of passing coaches. Smalt, which is crushed, ground glass colored blue with cobalt, had been used for centuries as a substitute for the expensive blue pigment lapis lazuli. Numerous early recipes for the preparation of smalt are known, but they all mention mixing zaffre, a deep blue pigment obtained by roasting cobalt ore, with sand and potash.16 Because it is a glass, smalt is transparent unless colored, and its vitreous particles are highly reflective. However, as particles of smalt are ground finer, their reflective quality is lost and color saturation lowered, so the compound was left fairly coarse.

The technique of applying smalt, which is known as “strewing,” required considerable skill and patience. After construction and painting of the image, the sign would have laid flat while a liquid adhesive was applied, and after it had dried sufficiently, smalt was sprinkled over it, little by little, and allowed to settle until it built into a solid layer. When the smalt had thoroughly dried, which could take a day or two, the sign would have been turned upright, with any excess falling off. Since the same process was used on both sides, adding lettering to a sign like the Canal Hotel’s was a lengthy endeavor.

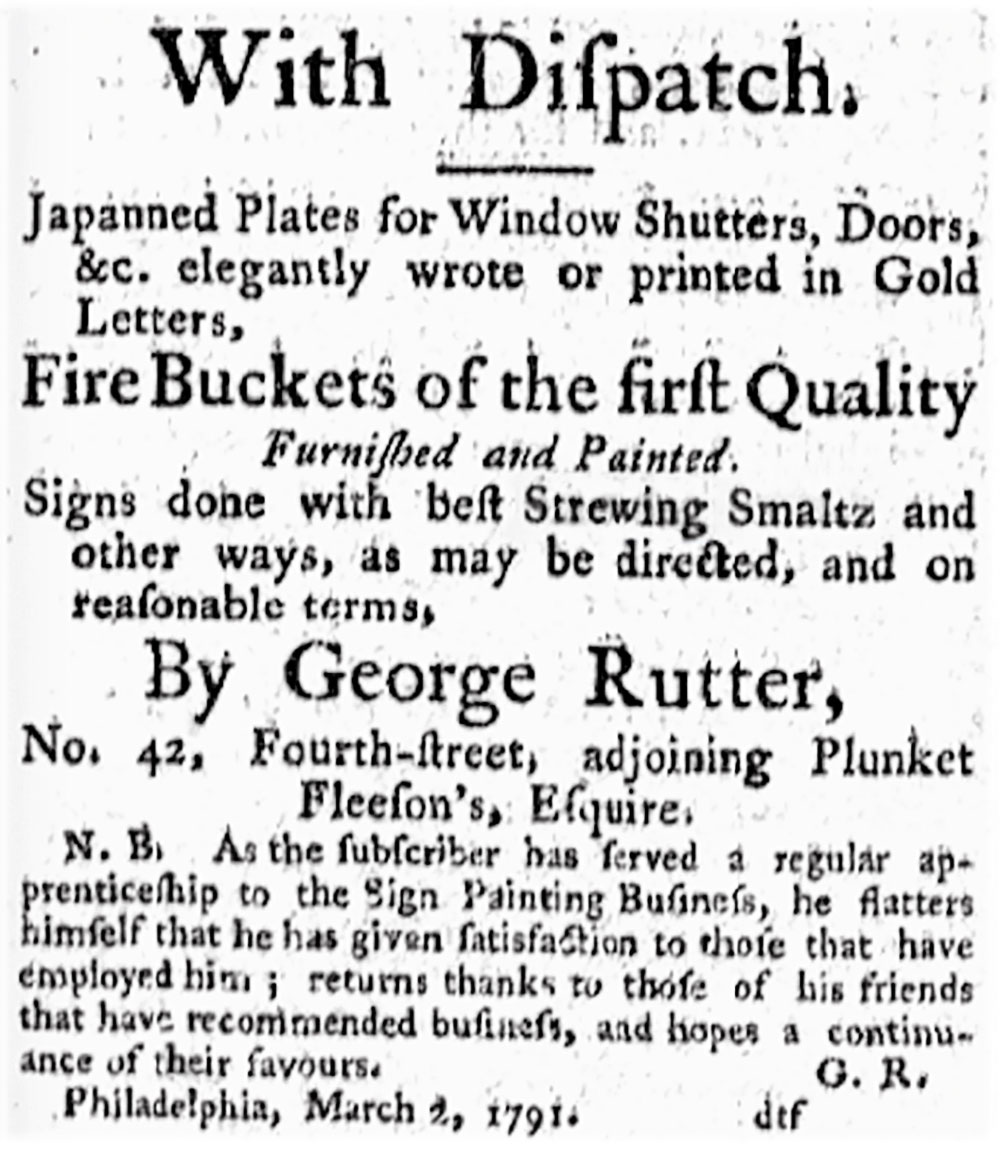

The Canal Hotel sign is possibly the earliest extant example of a smalt-strewn sign, a type that proliferated later in the nineteenth century, when they were produced by specialized sign shops. As early as the eighteenth century, professional sign makers advertised their use of smalt as a durable, textured background to set off the gilded lettering. The use of smalt and gilding on the Canal Hotel sign probably followed the method of sign making documented in these early American advertisements. Colonial signs were made by jack-of-all-trades artisans whose business encompassed painting tavern signs, fire buckets, coach doors, theatre scenery, and house decorations (Fig. 11).17 Smalt was one of the pigments sold to artisans by “colourmen,” druggists who also sold art supplies. This pattern of decorative painters purchasing goods from colourmen, and working closely with the building and furniture making trades as “finishers” or “grainers” continued after the Revolution. The painters were often self-taught, but an apprentice system did develop in the late eighteenth century.

St. John apparently had work done on the Old Stone House before he opened it to the public, and his workers may have made or helped in the making of the sign. A 1981 structural evaluation of the building discovered considerable updating in the Federal style with installation of plaster ceilings, marble mantelpieces, new doors, and wood sheathing that was still intact. It is possible that the carpenters who worked on the house constructed the sign, and the sign’s painter could have worked with them as a decorative painter or “finisher.”18

The architectural frame of the sign consists of upper and lower rails, with the upper rail identifying CANAL HOTEL in black block lettering. Two turned vertical posts are topped by finials, with a third finial surmounting a stylized scrolled broken-arch motif. The tall, distinctive urn-shaped finials of the sign echo the decoration found on some early chairs from New York and New Jersey. In his article “Early New York turned Chairs: A Stoelendraaier’s Concept,” American furniture scholar Erik Gronning notes that “in the Netherlands, spindle-back chairs were typically made by a specific class of artisan that specialized in the production of turned seating.”19 A number of these Dutch turners and chairmakers, called drayers, had immigrated to New Amsterdam (from 1664 New York) by the mid-1650s. The silhouette of the finials is one of the distinctive features of their chair style (Figs. 12, 13). “Degraded versions of these finials appear on chairs made in New York and New Jersey as late as the twentieth century,” Gronning writes. “The lingering and geographic distribution of this design is directly related to the settlement and cultural history of New York.”20

According to Schoelwer, in colonial America, “Tavern signs originated from the practical need to identify dwellings licensed to provide entertainment to travelers—entertainment being the period term for essential services, including food, drink, and lodging, as well as feed and stabling for horses.”21 The concept of a “hotel” first began appearing in American newspapers at the end of the eighteenth century, when the term most often referred to a European building used by royalty or the aristocracy to provide accommodations and care for their visitors. The word is “borrowed from the French hôtel, going back to Old French hostel, ostel ‘lodging, accommodation.’”22 In America after the Revolutionary War, as Margaret C. Vincent has shown, the term hotel “seems to have implied a new concern in hostelry, originating primarily in cities, generally denoting larger, nondomestic structures built specifically for the purpose, and encompassing such amenities as individual rooms, private parlors, separate dining and drinking areas, and meeting spaces.”23

A few smaller accommodations outside the cities began to call themselves “hotels” in the late 1790s. These were usually situated along transportation routes, initially stagecoach roads and canals (Fig. 14). Perhaps St. John used the term “hotel” to add distinction to his establishment. As a piece of advertising, the sign displays a variety of attractions for travelers and boarders: it was a “hotel” with pastureland for horses, comestibles and drink for their riders, proximity to the canal and roads, and a well-known innkeeper, and it was associated with an up-and-coming social-networking fraternity.

More About Stephen St. John

Stephen St. John was born in Norwalk, Connecticut, in 1788, the year that the U.S. Constitution was ratified. Around 1803, St. John left home for New York City, where he apprenticed himself to a shoemaker. According to a later biographical sketch, he “made rapid progress, and soon gained the trust and confidence of his employer by his strict attention to business, his industry and integrity.”24 After several years in this trade, he left the city to start a business of his own in Deerpark, in Orange County, New York. St. John operated a small store there until 1808, when he formed a partnership with Holly Seely. Together, they purchased a tannery that developed into a large, well-respected business. St. John’s partnership with Mr. Seely continued until St. John enlisted during the War of 1812, serving until 1815.

After completing his service, St. John returned to the Deerpark area where he married Abigail Horton in 1816. He also formed a new and long-lasting partnership with Benjamin Dodge and opened another store. St. John and Dodge then moved their business to Mount Hope where they opened a new store, conveniently located at the junction of two turnpikes, the Mount Hope and Lumberland Turnpike and the Minisink and Montgomery Turnpike, which stretched from Orange County to Narrowsburgh, New York, and later to Honesdale, Pennsylvania. Benjamin Dodge was one of the directors, and he benefited from tolls collected as well as from the business the turnpikes brought to his store. In 1825, St. John and Dodge purchased a large tract of forested land in Lumberland, New York, where they built logging mills and transported their lumber down the Delaware River to market until the 1840s.

As recounted earlier, Dodge and St. John bought the Old Stone House in 1819, and St. John opened the Canal Hotel there around 1826. Ten years later, St. John moved into a newly built home on what is now West Main Street in Port Jervis, and the Old Stone House became a rental property. He served as an advisor to D&H company managers and engineers, continuing in this capacity until his death. Again in partnership with Benjamin Dodge, St. John built and ran a store near the canal bridge until he retired from the firm of Dodge, St. John and Company in 1839. In 1846, St. John made another provident business move: he subdivided the remaining acres of his farm, selling sixty acres for one hundred dollars per acre to the New York and Erie Rail Road after learning that they were advancing their line from Middletown to Port Jervis in a plan to connect the region to New York City. The main railyards and a division center were developed on this land. Since the trains required frequent fueling, or “wooding up,” the lumber business in the region also benefited.

St. John became an affluent community leader: he supported the Deerpark Reformed Church, served as school commissioner, and sat on the first Board of Directors of the Bank of Port Jervis. He was an active member of the Port Jervis Masons and, since it is featured on his sign, he presumably was also a member of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows. Abigail St. John died in early 1870, and her husband passed on August 30 of that year.

Acknowledgments

About the Authors

1 "The town of Deerpark included several hamlets within its large boundaries, including “the lower neighborhood,” where St. John had settled and which was later partitioned to become Port Jervis.

2 “A Bit of Local History: Brief Sketch of the Old Stone House in Germantown,” Evening Gazette (Port Jervis, NY), August 13, 1887.

3 Ibid.

4 A prior inspection of the joints in the stone of the house by Peter Osborne, then director of the Minisink Historical Society, substantiated that a line separated the old and new work.

5 Albert Gallatin, Report of the Secretary of the Treasury; On the Subject of Public Roads and Canals (Washington, DC: R.C. Weightman, 1808), 8, oll.libertyfund.org

6 According to the Minisink Valley Historical Society, “The area known as ‘The Minisink’ or ‘The Minisinks’ is not a clearly defined area in any of the histories written about the region. [The region] generally follows the Delaware River. As one gets closer to the American Revolution the area shrinks in size and following the war the name went out of use because the area was divided up into towns and villages.” “Maps of the Minisink Region,” Minisink Valley Historical Society.

7 John Bloomfield Jervis (1795–1885) was the chief engineer of three canal projects. In 1828 he arranged to import from England, according to his specifications, the first steam locomotive to run in America, for use on the D&H gravity railroad. In 1832 he designed the first American locomotive with four of six wheels mounted on a swiveling truck. He supervised the construction of five of America’s first railroads. He designed and built the forty-one-mile Croton Aqueduct, which supplied water to New York from 1842 to 1891.

8 David Kirby, “A Main Artery of the 1800’s,” New York Times, August 25, 2002.

9 The Cuddeback progenitor, Jacob, arrived with the first wave of settlers to the region. “In 1697 a Patent was granted to Arent Schuyler for lands described . . . in the Minsink country, in the province of New York, called by the native Indians Warenasaghskenniek . . . . Another of these floating patents was granted in the same year to Jacob Codebeck (Cuddeback), Thomas Swartout, Anthony Swartout, Bernardus Swartout, Jan Fys, Peter Germar and David Jamison. This was located in what was called Peenpack.” Charles E. Stickney, A History of the Minisink Region (Middletown, NY: Coe Finch and I.F. Guiwits, 1867), 24.

10 The authors purchased the sign in 1993 and sold it at auction in 2019.

11 Nancy Finlay, “Lions and Eagles and Other Images on Early Inn Signs,” in Lions & Eagles & Bulls: Early American Tavern and Inn Signs from the Connecticut Historical Society, ed. Susan P. Schoelwer, (Hartford: Connecticut Historical Society in association with Princeton University Press, 2000), 56.

12 For example, the sign for the Tarbox Inn: The original innkeeper was Thomas Tarbox, licensed 1807–1824 in Scantic, East Windsor township, Connecticut. The name and 1807 date were subsequently overpainted in 1824, after Tarbox’s death, by Ephraim Ely, who acquired a tavern license and moved the sign to a rental location. A third owner, Isaac G. Allen, was licensed in 1831, presumably prompting the large gilt-lettering “Village Hotel” on the reverse side. Allen was licensed in Enfield, Connecticut, 1831–1833, and then in East Hartford, 1835–1836.

13 Susan P. Schoelwer, “Afterword: Signs in American Art and Cultural History,” in Lions & Eagles & Bulls, 102.

14 “From 1672 on, every licensed innkeeper in Connecticut was required by law to mark his or her establishment with ‘some suitable Signe set up in the view of all Passengers for the direction of Strangers where to go, where they may have entertainment.’” Susan P. Schoelwer, “Tavern Signs Mark Changes in Travel, Innkeeping, and Artistic Practice,” ConnecticutHistory.org, June 1, 2021.

15 “The Independent Order of Odd Fellows was founded on the North American Continent in Baltimore, Maryland, on April 26, 1819 when Thomas Wildey and four members of the Order from England instituted Washington Lodge No. 1.” “About Us,” Independent Order of Odd Fellows, Sovereign Grand Lodge.

16 Zaffre is made of either an impure form of cobalt oxide or impure cobalt arseniate.

17 “In April 1788 John Penn spent the night in Trappe at George Brooke’s tavern . . . . [T]he next day, Penn paused to admire the tavern’s sign, a likeness of Benjamin Franklin, which he noted was made by George Rutter, an ornamental painter and gilder in Philadelphia. Among Rutter’s best-known works is the Pennsylvania coat of arms that he made in 1785 for the State House, its frame carved by Martin Jugiez.” Lisa Minardi, “Philadelphia, Furniture, and the Pennsylvania Germans: A Reevaluation,” American Furniture (2013).

18 The evaluation was done by Donald G. Carpenter, founder and director of Historic Eastville Village in East Nassau, New York.

19 Erik Gronning, “Early New York Turned Chairs: A Stoelendraaier’s Concept,” American Furniture (2001): 89.

20 Ibid, 102.

21 Schoelwer, “Tavern Signs Mark Changes.”

22 Merriam-Webster, s.v. “hotel (n.).”

23 Margaret C. Vincent, “‘Some suitable Signe . . . for the direction of Strangers’: Signboards and the Enterprise of Innkeeping in Connecticut,” in Lion & Eagles & Bulls, 49.

24 “Sketch of His Life—A Self-Made Man—A Life that was a Success—His Early Years and How He Spent Them,” Evening Gazette (Port Jervis, NY), September 1, 1870.