Jewelry in American Folk Portraits

American folk portraits tell the private stories of their sitters and the broader narrative of the cultural and economic development of a new nation. The jewelry worn by women and children in these portraits reveals aspects of the social status, personal values, and mourning customs of the sitters. A close look at the jewelry depicted in a sampling of early American portraits highlights the recurring cultural themes of sentimentality and novelty in nineteenth-century society.

New England artist Ruth Henshaw Bascom (1772–1848) was an active and sensitive portraitist who worked from about 1820 to 1845.1 Nearly two hundred of the delicate likenesses she created for friends, neighbors, and family are known. Her choices of media and pose were distinctive; she created profile images outlined in pencil and colored with pastel crayons that she then cut out and mounted on separate background paper. On June 27, 1840, Bascom drew a portrait of eight-year-old Eliza Jane Fay in Fitzwilliam, New Hampshire (Fig. 1). Bascom noted in her diary: “Eliza Fay called after the Juvenile singing school to set for her [picture] began today.”2 Young Eliza’s hair is shown tucked behind her ear to reveal a small flower-shaped earring set with seed pearls and coral. She also wears a miniature gold charm that hangs from a black ribbon. Inscribed “In Memy / Geo. / Washingt,” Eliza’s locket is an example of a style worn by many women and children during the early nineteenth century—a neoclassical mourning miniature inspired by popular images of memorials to George Washington.3

The death of Washington in December 1799 sunk Americans into a collective culture of mourning, as the young nation united in grief and national pride.4 This traumatic event combined with European examples to lead to the advent of the neoclassical mourning picture, a sentimental and distinctly American artistic style of symbolism grounded in the ideals of liberty and sacrifice. The lasting popularity of this antebellum style is evidenced in a profusion of tokens of mourning made by both professional jewelers and young students in female academies. In his 1859 travel memoir, Life and Liberty in America, Charles Mackay observed, “Mount Vernon, the home and tomb of George Washington, is the sacred spot of the North American continent whither pilgrims repair, and on passing whichever steam-boat solemnly tolls a bell and every passenger uncovers his head, in expression of the national reverence.”5

An engraving by Thomas Clarke from 1801 (Fig. 2) exemplifies Mackay’s observations, and it served as a source for many mourning pictures made by both schoolgirls in academies and professional artists. The tomb in the engraving relates closely to the tomb depicted in Eliza’s miniature. The engraving depicts grieving figures at George Washington’s tomb and illustrates the societal norms of mourning and patriotism that inspired the fashion for rings, lockets, and brooches with miniature memorial pictures. These were usually painted on ivory, but occasionally an example can be found that was painted on paper. The memorial pendant in Figure 3 (Fig. 3) contains a tiny watercolor on paper depicting a weeping, dramatically posed woman leaning on a monument framed by colorful trees and foliage, very finely rendered in a charmingly expressive style.

In a diary entry in 1810, Bascom reflected on the importance of Christian duty.6 At this time, Christian values became interwoven with ideals of liberty and patriotism in the minds of many Americans.7 In Eliza’s portrait, Bascom turned her subject’s torso slightly, to a three-quarter view, to clearly display her mourning miniature, and thus ensured that she was presented as a fashionable, patriotic, and virtuous New England girl who held the values of her generation close to her heart.

Another popular and highly personal form of jewelry sometimes depicted in folk portraits was a miniature locket embellished with human hair (Fig. 4). A portrait by an unknown artist from the 1830s shows a woman wearing such a locket on a gold watch chain (Fig. 5). The sitter wears a blue satin dress with large puffed sleeves and lace trim, as was fashionable around 1830. Her curled hair is held in place by a pearl-set ribbon ferronnière, a type of band worn around the forehead. This fashion was reported in the New York Herald to have been seen in London and Paris: “across the forehead, a very narrow band of velvet and a rose on each temple. A row of small pearls may be substituted for the velvet.”8 The sitter’s hairwork locket likely served to commemorate a deceased loved one.

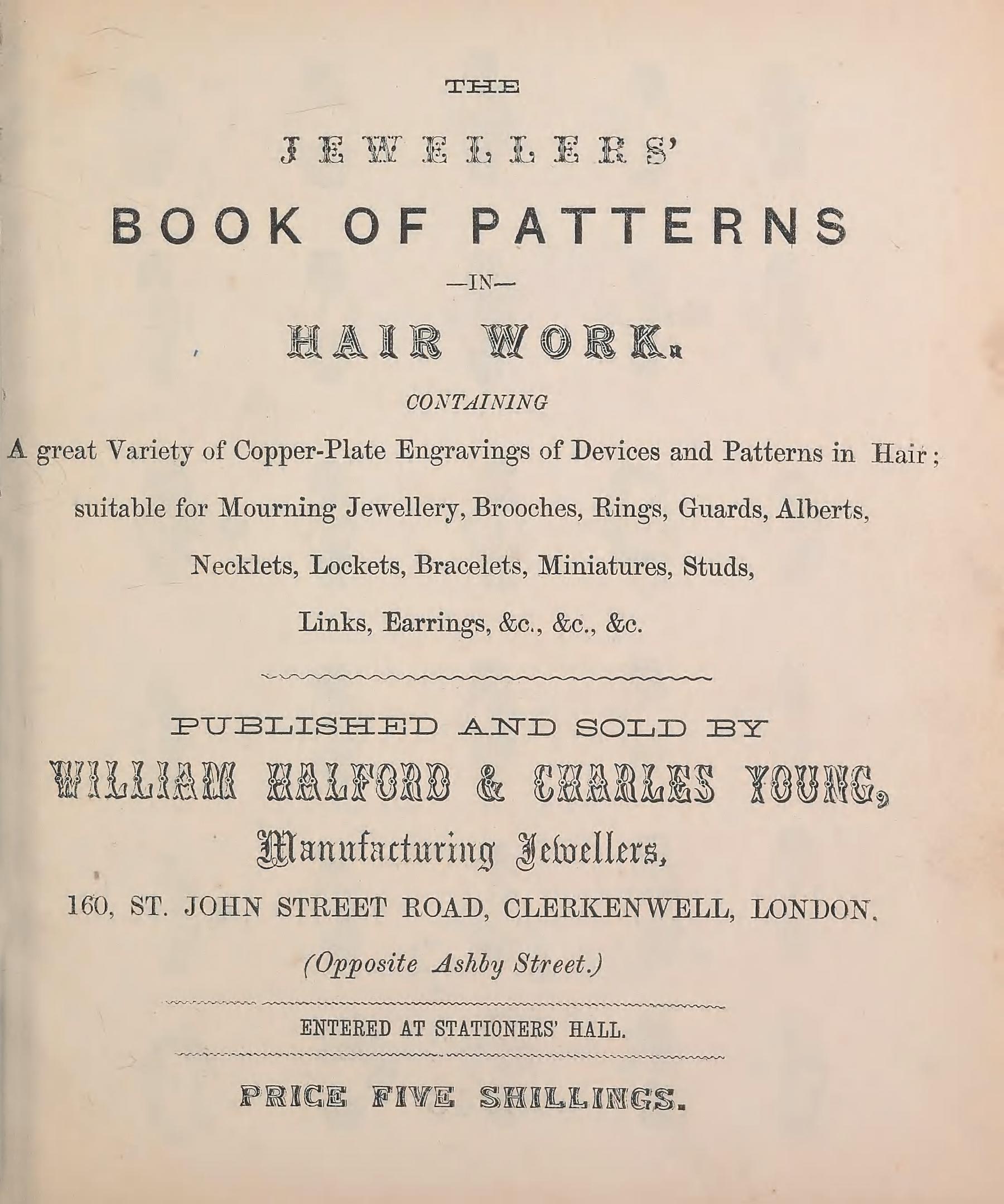

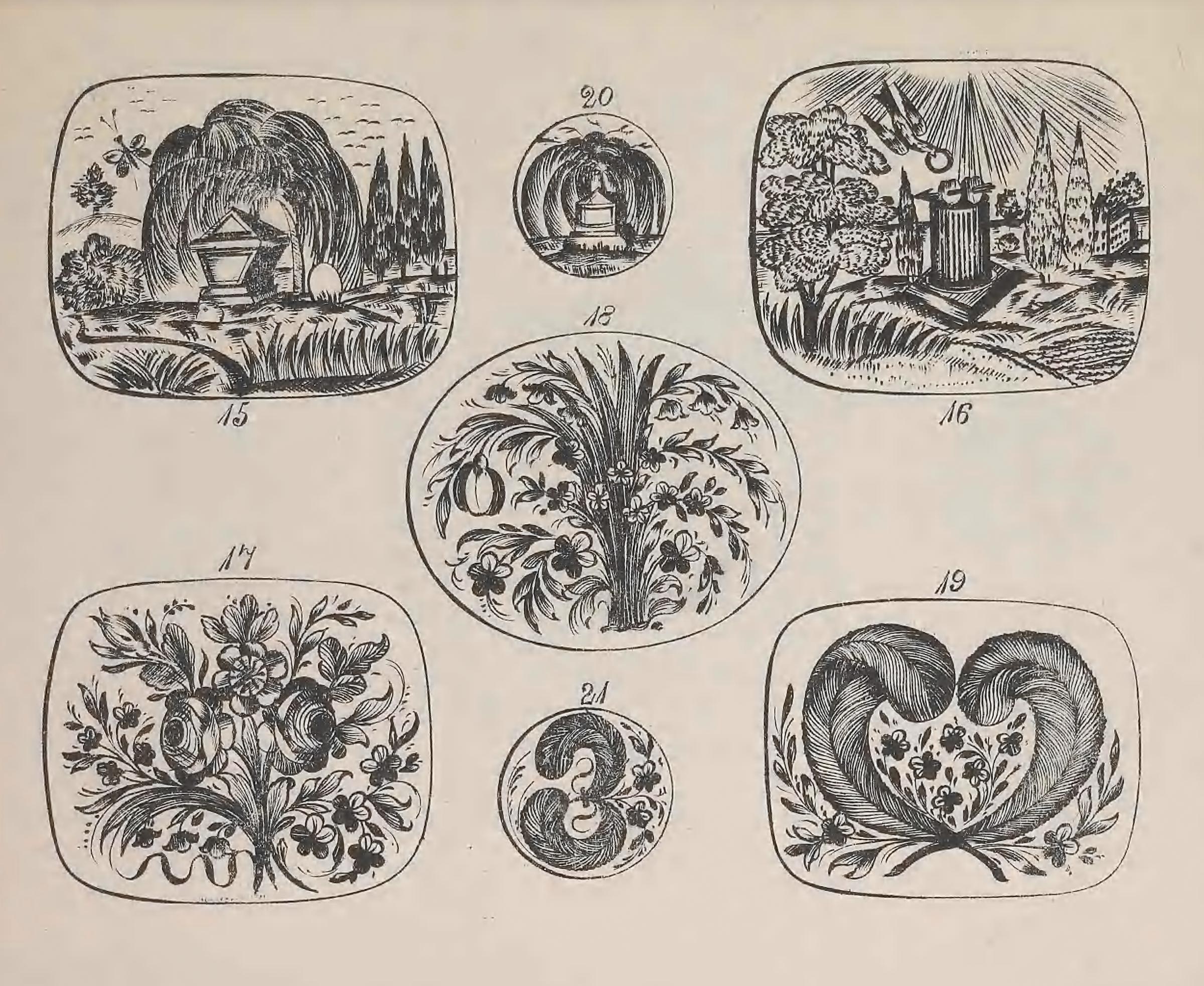

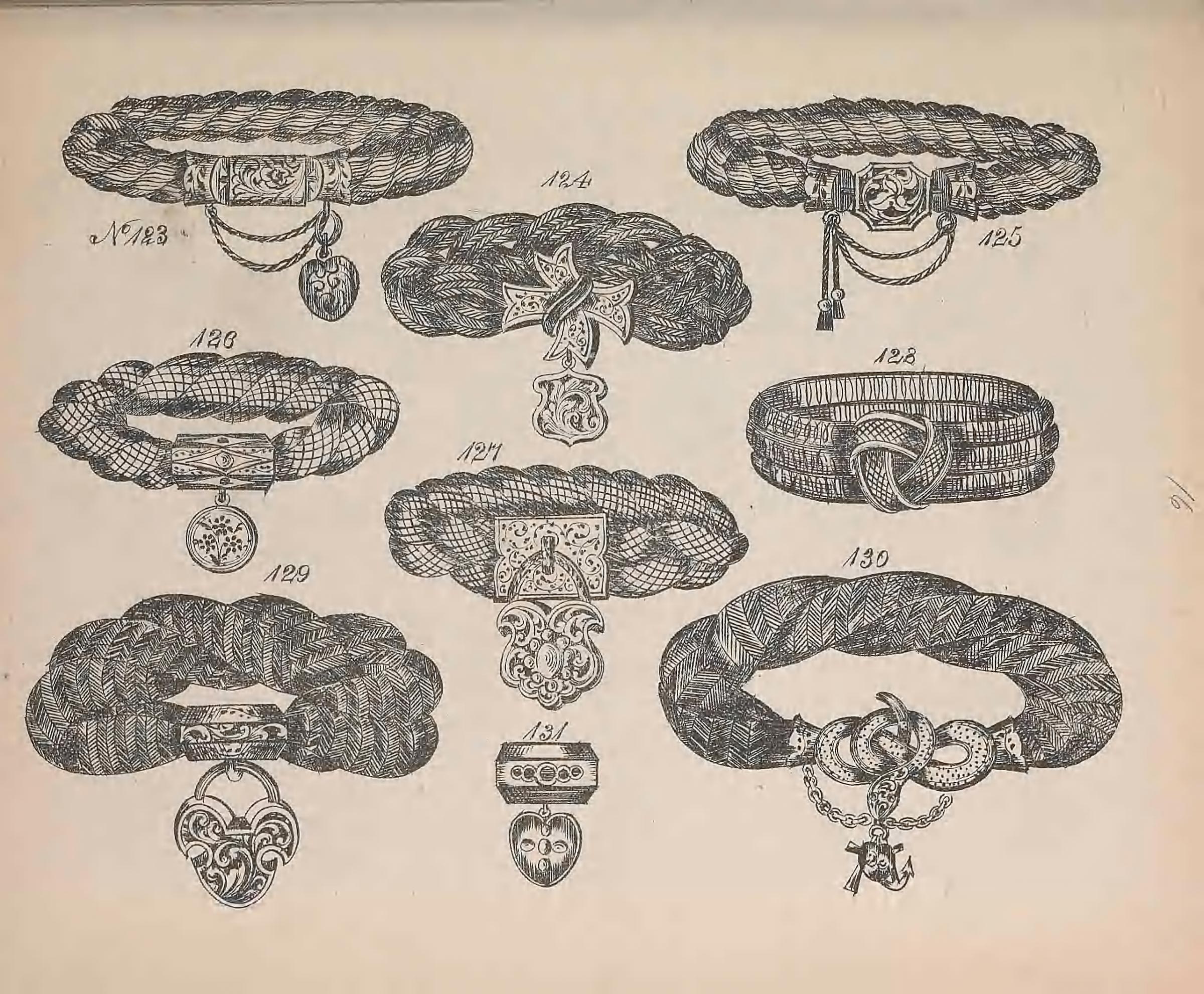

As the century progressed, hairwork evolved into an art of its own in both Europe and America, and it is frequently seen in friendship tokens made by young girls in academies as well as in mourning jewelry made by professional jewelers. In 1867, Mark Campbell, a jeweler who specialized in hairwork, published a magnum opus on the art of creating jewelry designs from human hair. In Hair Jewelry of Every Description: Compiled from Original Designs and the Latest Parisian Patterns, Campbell instructed, “The making of Hair Flowers is very simple, and yet of course everyone has first to learn it. Supply yourself with as many different colors of hair as you can, and by applying Gum Tragacanth, it renders it capable of being cut into any shape you may wish. . . . Anyone possessing the least artistic skill can make any flower or picture that they may desire. . . . All articles intended to be worn as jewelry, should of course be mounted in gold.”9 The hairwork process involved flattening hair on a palette, treating it with adhesive, cutting, curling, or braiding it, and setting it into complex and symbolic designs.10 Motifs such as Prince of Wales feathers and weeping willows were often embellished with miniature paintings, enamel, gemstones, gold foil, or seed pearls. The Jewellers’ Book of Patterns in Hair Work (Figs. 6a, 6b), also published in 1867, offers further evidence of the staying power of this fashion into the third quarter of the nineteenth century. The book provided a multitude of fashionable examples and patterns for American jewelers to emulate, including inspiration for the popular designs pictured in Figures 4 and 5 (Figs. 4, 5). A portrait by an unknown artist of a woman making a hairwork bracelet appears in Figures 7a and 7b (Figs. 7a, 7b). She holds a weaving tool in her right hand and a partly finished bracelet in her left. The bracelet is made of intricately woven hair and includes a drop pendant similar to those seen in Campbell’s pattern book (Fig. 8) and in a bracelet shown in Figure 9 (Fig. 9).

Hairwork jewelry reflects the sentimentality and culture of mourning in the nineteenth century, when Americans wore their most personal emotions and precious memories as public displays for all to see. Death touched everyone; although data is sparse and hotly debated among modern analysts, average life expectancy of white men and women in the 1840s was about forty-four years. Many women died in childbirth, and forty-three percent of children died before they were five, primarily from infectious diseases. These high rates remained fairly consistent until about 1880, when they began to steadily, albeit slowly, decline.11

Hairwork miniatures served as mementos of the personal connections made between friends and loved ones. They kept memories accessible and part of everyday lives at a time when mourning was, as scholar Mary Louise Kete has noted, “the primary spiritual and social event in the American’s life.”12 In this tradition, Campbell advised, “Persons wishing to preserve and weave into lasting mementos the hair of a deceased father, mother, sister, brother, or child, can also enjoy the inexpressible advantage and satisfaction of knowing that the material of their own handiwork is the actual hair of the ‘loved and gone.’”13

Coral is another material that appears frequently in folk paintings. In Ammi Phillips’s (1788–1865) c. 1825 portrait Mother and Child in Grey Dresses (Fig. 10), the little girl is wearing a coral necklace and armlets. A similar necklace and armlets are illustrated in Figure 11 (Fig. 11). The mother cradles her daughter on her lap and tenderly holds the child’s hand in her own. The coral the child wears was harvested in the Mediterranean, and the jewelry pieces were likely made in Italy and exported to the American market. Smooth beads were worn by children from the colonial period into the nineteenth century, and both smooth and natural branch-form beads are frequently seen in folk portraits.

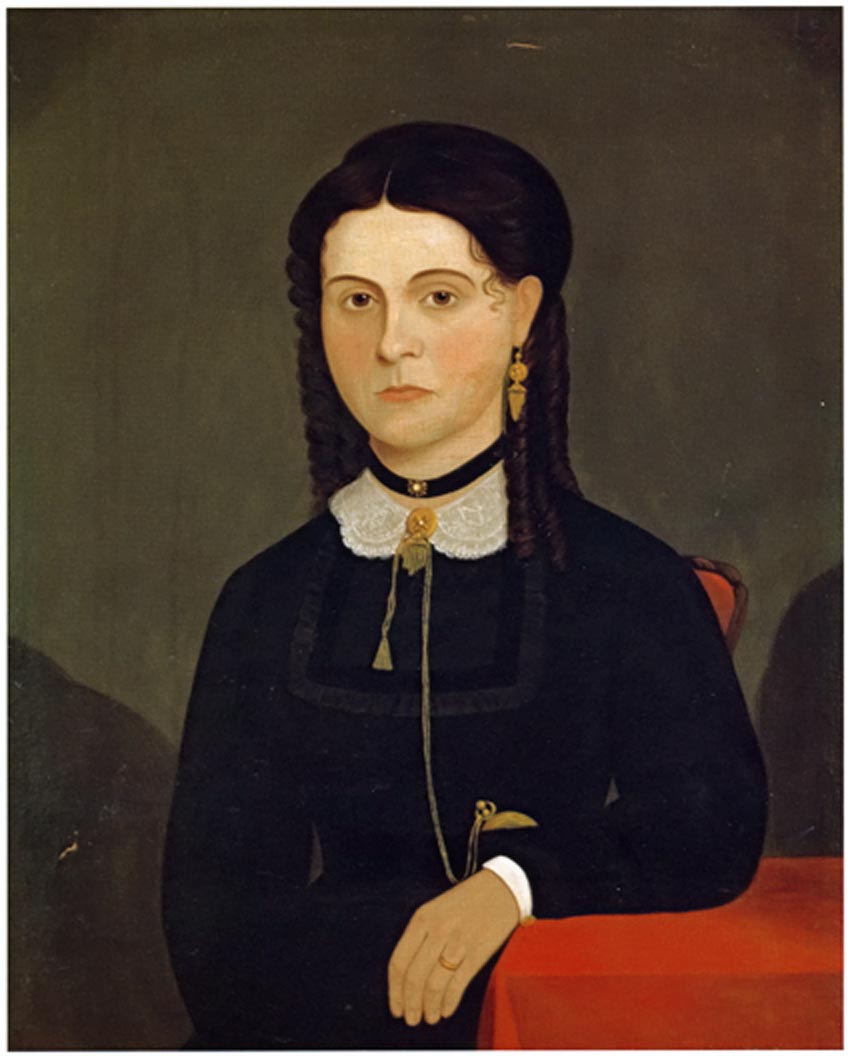

A growing middle class of merchants, farmers, and professionals provided clientele for the prolific itinerant limner William Matthew Prior (1806–1873). Prior painted detailed, realistic likenesses at higher prices and quicker “flat” images at lower rates. By doing so, he was able to provide a service that was in high demand to people in a variety of income brackets. One particularly elegant portrait that Prior painted “with shadow” depicts a young lady with long brown ringlet curls wearing a formal pleated blue dress with lace trim (Fig. 13).17 The unidentified sitter wears a floral cameo brooch with a flying dove that is similar to the brooch pictured in Figure 14 (Fig. 14). Prior was careful to execute the details of the cameo with loose swirling brush strokes, which give the dove a sense of motion. Made from coral, considered an exotic material at the time, and carved by sculptors in Italy or immigrant artisans in America, cameos like this advertised refinement, sophistication, and the new gentility that was now within reach of the middle class.18

Prior’s portrait of Phebe Ann Carlton Hawes (Fig. 15), painted in his “flat style,” includes another popular type of jewelry. Hawes wears gold drop earrings, a necklace which is likely made from woven hair, and a mosaic floral brooch. Like coral pieces, mosaics advertised a level of prosperity for the wearer. Mosaic jewelry was traditionally made in Italy, and the most refined work was crafted at the Vatican studios in Rome. Imported pieces were available to Americans who were not able to afford a Grand Tour of Europe. These Americans read about the riches of the Italian workshops in their local newspapers, in items such as this report, filed from Rome by a Miss Tylor, for an 1840 edition of Mississippi’s Lexington Union:

Leaving St. Peter’s, we walked to see the manufactory of mosaic. . . . The material used . . . is a composition of lead and glass and with colours; of this there are said to be eighteen thousand shades. We walked through a long room, lined with cases in which this is arranged, to the workshops. Here we watched the progress of the mosaic manufacture for some time.19

Scholar Martha Fales describes the process of making mosaics: “Spun filaments of colored glass were cut into tiny tesserae, which were affixed to a stucco ground held by a metal or stone plate. The resulting plaques could be mounted into jewelry.”20 Mosaic earrings, bracelets, pendants, and brooches were made in two styles—Roman and Florentine. The Florentine examples incorporated small pieces of stone instead of glass, and these were also popular in America. Mosaic jewelry was prominently featured in the Christmas display at Tiffany & Co. in 1863 described in the New York Herald: “The very large assortment of lower priced . . . mosaics . . . contained beautifully worked specimens and some . . . cannot be distinguished from miniature paintings; some represent harvest scenes, some Amor and Hyman; some have doves, some butterflies in all the splendor of their natural colors.”21 A colorful floral Roman style brooch similar to Hawes’s is pictured in Figure 16 (Fig. 16).

In 1835, Vermont-born itinerant limner Asahel Lynde Powers (1813–1843) painted a portrait of Eliza Ann Farrar in Ringe, New Hampshire (Fig. 17), one of a group of portraits of members of the Farrar family he rendered.22 Farrar sits in a Fancy painted armchair and wears a fashionable dress with enormous sleeves embellished with lace and red satin ribbon bows.23 Her matching red satin belt is fastened with a silver buckle, and she carries an elaborately beaded pocketbook. She wears the torpedo-shaped gold earrings that were poplar during the 1830s and 1840s (Fig. 18). These elongated earrings were made from thin gold sheets to keep them light for the wearer’s comfort. They were often embellished with delicate embossed gold work or engraving. The exaggerated vertical lines of these pieces served to balance the horizontal silhouette resulting from the puffed curls that were worn at the sides of the face at the time.

Farrar’s gold watch hangs from a long chain made of tiny glass beads in a repeated pattern of solid and open-work beading. The sitter may well have made the chain herself. Beaded chains were a popular fad during the 1830s, as both a craft for young ladies and as fashionable jewelry. Inspired by the societal value of domesticity, girls and young women learned the art of beading on specially designed looms.24 Women exhibited their skill and creativity in these chains, as they did with samplers, quilts, and theorem paintings. Scholar Joyce Appleby has noted that a woman’s mastery of these domestic skills was valued as an element of refinement.25

Sentimental phrases were sometimes beaded into the designs, such as a chain with the phrase “To the memory of C.E. and H Furness Sweet babes the arrows of calamity can never reach you – you are forever at rest.”26 Another example is inscribed “A New Year’s Gift M.S.T” (Fig. 19). Chains such as these were given as gifts and tokens of friendship among school girls and women. In her discussion of the popular culture of gift-giving, Kete explains that “in this tradition, material articles become specially imbued with emotions of the people who come into contact with them through mere association or through the process of production and exchange.”27 The chain in Figure 20 (Fig. 20) has alternating sections of open and closed beadwork similar to Farrar’s chain in the Powers portrait.

A portrait of a young African American girl (Fig. 21), formerly in the collection of the Dewitt Historical Society, in Ithaca, New York (now the History Center in Tompkins County), displays the sitter’s academic accomplishment and the socioeconomic status of her family. Few portraits of antebellum Black children have survived. Her family was likely part of a small group of prosperous African Americans in New York State.28 This portrait, painted in about 1850, shows the girl in a white dress with puffed sleeves, holding an open book in one hand and a gold pocket watch and fob in the other. The watch is prominently displayed to highlight her family’s position in the local community.

By the early 1800s, both men and women wore pocket watches as jewelry (Fig. 22). Pocket watches grew in popularity as they became more affordable through mass production in America in the 1840s and an influx of European watches in the 1850s and 1860s.29 Along with the watches and their keys, decorative fobs, like gold seals and trinkets, were displayed on chains like charms are worn today on bracelets. Fobs were sometimes set with gems, such as amethyst, garnets, coral, carnelian, or different colored pastes. Hairwork fobs were popular as well: the M. Scott Ladies Ornamental Hairwork Manufactory in Baltimore advertised “watch fobs plaited in the neatest manner.”30 Pocket watches were symbols of respectability that represented self-regulation, reliability, and conspicuous yet refined consumption—the cornerstones of gentility.31

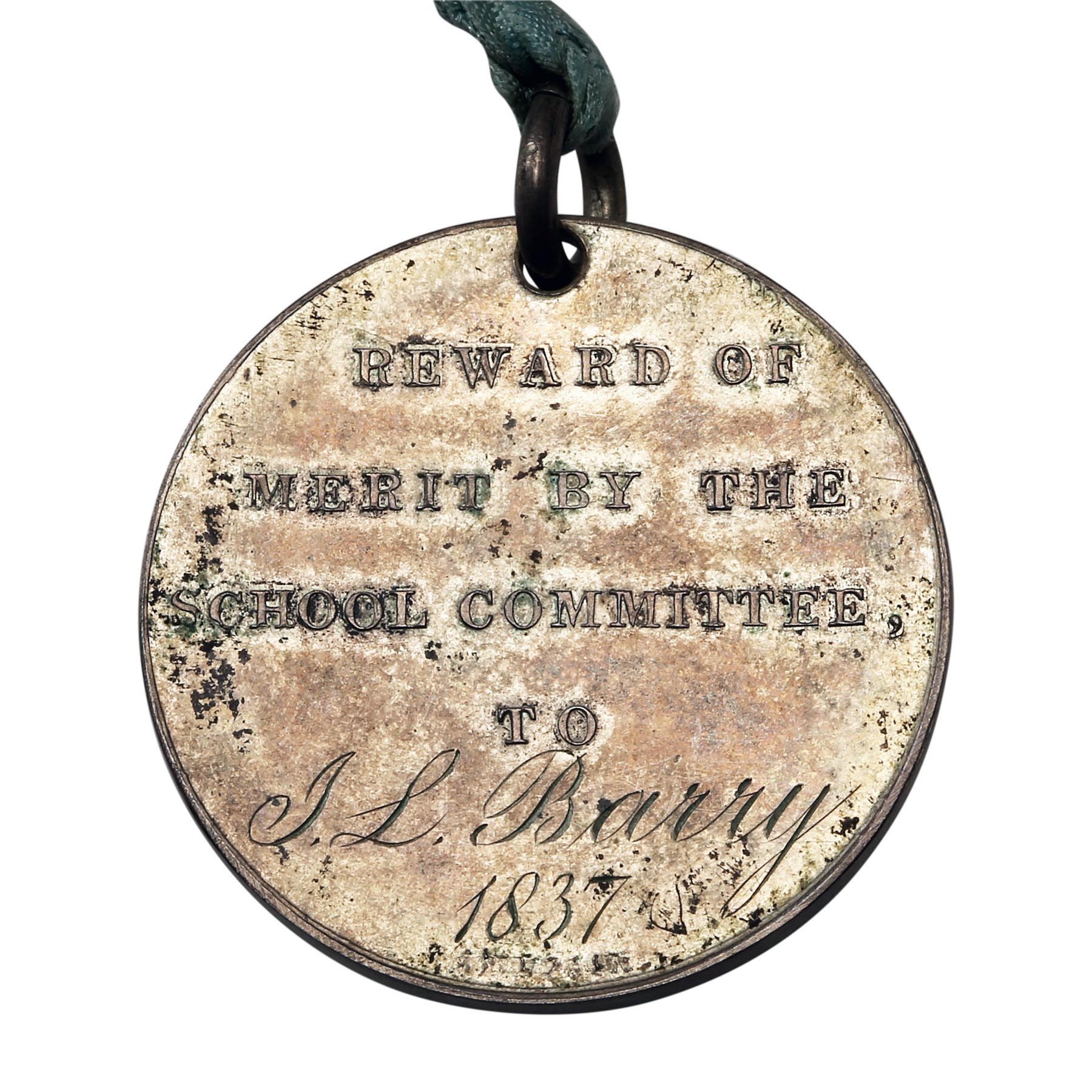

In addition, a white metal engraved school medal hangs from a ribbon around the girl’s neck, representing an affluent and literate young Black child proudly displaying her academic achievement. The tradition of awarding academic medals to white students became very popular during the Federal period and continued throughout the century. The New York State Board of Regents was the first board of education to organize in this country, and public schools were formed in New York as early as 1812. During the 1820s and 1830s, several female academies opened in the Tompkins County area of rural upstate New York, where this portrait was likely painted. Among these were Mrs. Phelps’ School for Young Ladies, Miss McDonald’s School for Young Ladies, and the Ithaca Female Seminary, which advertised in 1836 that primary classes would include “Reading, Spelling, History, and Botany.”32

Few Black children were admitted to female seminaries or public schools during the 1850s, when separate schools for children of color were formed in cities and rural areas. Segregated Sunday schools were established as early as 1790, in the tradition of the Sunday school movement in England, which provided education to poor and working children on their one day off from work. From the 1810s to the 1860s, there were 110 Black Sunday schools in New York State.33 Many of these were organized by African Methodist Episcopal churches, which provided both academic and religious instruction. Literacy was the first priority at Sunday schools, where the children learned to read and recite Bible verses.

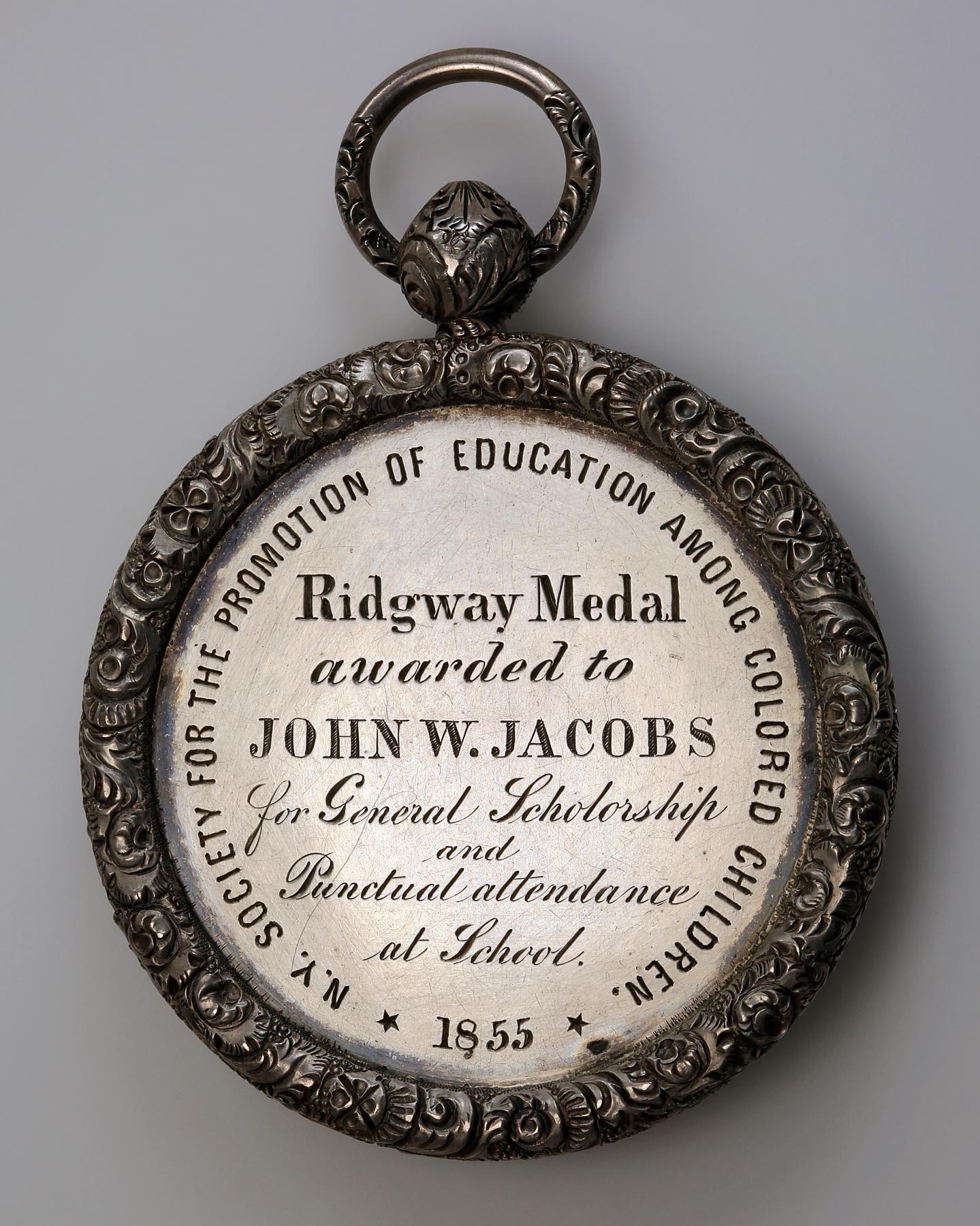

In 1847, mathematics professor Charles L. Reason founded the Society for the Promotion of Education Among Colored Children, an organization that created schools for Black children in New York City. This society awarded a medal of achievement to its students called the Ridgway Medal (Figs. 23a, 23b), which was awarded to John W. Jacobs in 1855 “for General Scholorship and Punctual attendance at School.”34 This elegantly engraved pictorial medal illustrates a classroom with a teacher and students and is inscribed “Knowledge is Power.”

The medal that the young girl in the portrait wears has a neoclassical bust on its front side and resembles the Franklin medals that were awarded to students in Boston schools (Figs. 24a, 24b). It is likely that the medal in the portrait was inspired by the Franklin medals, which served as models for school medals throughout the country. A medal inspired by Franklin medals from the same period as the portrait of the young girl is illustrated in Figures 25a and 25b (Figs. 25a, 25b). By proudly displaying her school medal in her portrait, the sitter’s family celebrated not only her refinement through literacy and academic achievement, but also their very survival and economic success as a free Black family and the hope they placed in future generations.

A portrait of Elizabeth Laverton Winn of Newburyport, Massachusetts, by an unknown artist exhibits the height of novelty and sophistication for a rural middle-class American woman in the 1860s (Fig. 26).35 Winn wears a black dress with a fashionable small lace collar, a demi-parure, or “partial set,” of gold earrings and a brooch, a gold watch and chain, and a black ribbon choker. As was customary, she tucked her gold watch chain into her brooch and tucked her watch into her belt. The earrings and brooch are set with pearls in the center of a gold medallion, and gold fringe hangs from all three pieces. Winn’s jewelry, which is influenced by the latest styles from Parisian jewelers, is painted with great care, as such a sitter wanted to be seen as a prosperous and genteel member of her community. The demi-parure is archeological revival style, which evinces the sitter’s sophisticated, European taste and the popularity of historicism in jewelry designs.

A renewed interest in ancient styles was sparked by the archeological discovery of meticulously made gold artifacts outside of Rome in the early 1800s. Among the discoveries were delicate Etruscan gold jewels crafted with ancient techniques previously unknown to contemporary metalworkers. These objects inspired the Castellani family of master jewelers in Rome to attempt to replicate the ancient work as closely as possible. They created unique designs in a style they dubbed “Italian archeological revival,” which incorporated antique-inspired ornament and metalwork methods.

The Great London Exposition in 1862 served to popularize and disseminate revivalist styles. Over time, Greek, Etruscan, and other historical revival designs were diluted and mass-produced in both Europe and America until they were only moderately related to the original works by Castellani. Winn’s jewelry appears to be an example of this style, which became very popular around 1870.36 Her brooch and earrings are “day-to-night” pieces, with detachable fringe providing a more formal look for evening wear, or in this case, for her portrait.

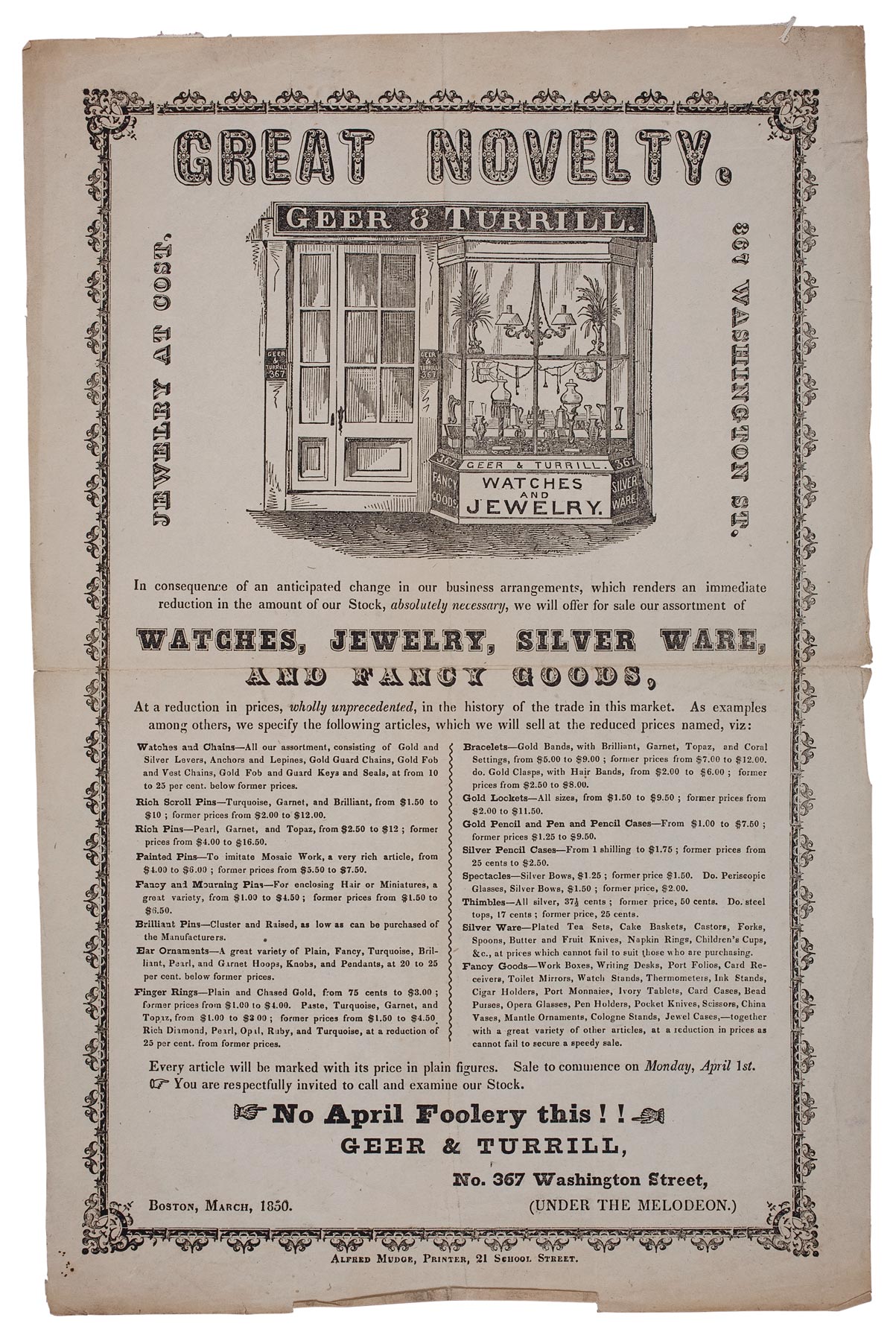

While more elaborate, with granulated gold decoration and turquoise stones, a similar suite to Winn’s is illustrated in Figure 27 (Fig. 27). Chokers were popular throughout the century, as an 1849 story in Peterson’s Magazine reveals: “Throat Ribbons – The fashion for wearing a band of velvet ribbon round the throat, which was so prevalent some years ago, has lately been partially revived.”37 These chokers were custom made of velvet or lace and set with diamonds or pearls, usually finished with a gold clasp. They were frequently worn with other necklaces, brooches, and watch chains. Winn likely obtained her jewelry in a shop that, like Geer & Turrill in Boston, advertised “Great Novelty” (Fig. 28).

Although the stoic expressions of sitters in American folk portraits rarely betray emotion, details of personal ornaments depicted in these paintings reveal both private and public aspects of the sitters’ lives. The history of young America’s cultural and industrial development is reflected in these likenesses. The jewelry worn by the sitters gives us glimpses into their individual lives, reflecting their socioeconomic status, their values and interests, and their sorrows and triumphs.

Acknowledgments

About the Author

1 Bascom was the daughter of American patriot and minuteman William Henshaw. She kept a daily journal of her extraordinarily busy life as a minister’s wife, church record keeper, stepmother, summer school teacher, librarian, milliner, and artist.

2 Lois Avigard, “Ruth Henshaw Bascom: A Youthful Viewpoint,” Clarion 12 (Fall 1987): 41.

3 Robin Jaffee Frank discusses this at length, with several examples of miniatures illustrated, in “The Cult of Washington,” in Love and Loss: American Portrait and Mourning Miniatures (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 97–117.

4 New York State Historical Association, Outward Signs of Inner Beliefs: Symbols of American Patriotism (New York State Historical Association, 1975), 6.

5 Charles Mackay, Life and Liberty or Sketches of a Tour in the United States and Canada, in America, 1857–1858 (New York: Harper Brothers, 1859), 225.

6 “Ruth Henshaw Bascom Papers Finding Aid,” American Antiquarian Society.

7 For a discussion of Christian values in the Federal period, see Joyce Appleby, Inheriting the Revolution: The First Generation of Americans (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2000), 195–238.

8 “London and Paris Fashions,” New York Herald, January 27, 1836.

9 Mark Campbell, Hair Jewelry of Every Description: Compiled from Original Designs and the Latest Parisian Patterns (Chicago: M. Campbell, 1867), 138.

10 For more details about this complex process, see Martha G. Fales, Jewelry in America 1600–1900 (London: Antique Collector’s Club, 1995), 216; and “Tender Remembrance: Victorian Hairwork,” Ohio Memory, Ohio History Connection and State Library of Ohio.

11 “Child Mortality Rate (Under Five Years Old) in the United States, from 1800 to 2020,” Statista.

12 Mary Louise Kete, Sentimental Collaborations: Mourning and Middle-Class Identity in Nineteenth-Century America (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2000), 59.

13 Campbell, Hair Jewelry, 18.

14 Catherine E. Kelly, “Mourning Becomes Them: The Death of Children in Nineteenth Century American Art,” Magazine Antiques, July 2016.

15 Pliny the Elder, Natural History, trans. John Bostock and H. T. Riley (London, 1855; Perseus Digital Library, Tufts University), chap. 11.

16 Alexandria (VA) Gazette and Daily Advertiser, April 29, 1818.

17 For a discussion of Prior’s career and the different styles of painting that he offered, see Patricia Johnston, “William Matthew Prior: Itinerant Portrait Painter,” Early American Life, June 1979, 20–23, 66.

18 Richard L. Bushman discusses gentility and refinement throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in rural and urban areas in The Refinement of America: Persons, Houses, Cities (New York: Vintage Books, 1993).

19 “From Miss Tylor’s ‘Letters from Italy,’” Lexington (MS) Union, December 19, 1840.

20 Fales, Jewelry in America, 239–40.

21 “Tiffany & Co. A Visit to the House and All its Different Departments,” New York Herald, December 23, 1863.

22 This portrait and other members of the Farrar family are illustrated in Nina Fletcher Little, Asahel Powers: Painter of Vermont Faces (Williamsburg, VA: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1973), 32–36.

23 For a comprehensive discussion and definition of Fancy, see Sumpter Priddy, American Fancy: Exuberance in the Arts 1790–1840 (Milwaukee: Chipstone Foundation, 2004). Priddy writes, “America’s artisans . . . [created] an astonishing range of Fancy artifacts that helped to meet the public’s rising desire to respond imaginatively to the surrounding world: brilliantly colored fabrics, vividly painted furniture, boldly patterned wallpapers, and whimsical ceramics, to name but a few,” xxvi.

24 Lynne Z. Bassett, “Woven Bead Chains of the 1830s,” Magazine Antiques, December, 1995, 798–807.

25 Appleby, Inheriting the Revolution, 148.

26 This chain is in the collection of the Peabody Essex Museum and illustrated in Bassett, “Woven Bead Chains of the 1830s,” 802.

27 Kete, Sentimental Collaboration, 105.

28 Carleton Mabee, Black Education in New York State: From Colonial to Modern Times (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1979), xiii–xiv.

29 For a history and analysis of pocket watch production, availability, and the repair industry, see Alexis McCrossen, “The ‘Very Delicate Construction’ of Pocket Watches and Time Consciousness in the Nineteeth-Century United States,” Winterthur Portfolio 44, no. 1 (Spring 2010): 1–30.

30 American Republican and Baltimore Daily Clipper, November 13, 1846.

31 For a discussion of the evolution of time consciousness and pocket watches, see Linda Young, Middle Class Culture in the Nineteenth Century: America, Australia, and Britain (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003) 84.

32 “Schools,” Tompkins County Public Library.

33 Mabee, Black Education in New York State, 36.

34 John Sallay, “The Ridgway Medal,” The MCA Advisory: The Newsletter of Medal Collectors of America 9, no. 9 (October, 2006): 4.

35 This portrait is illustrated in Dean L. Lahikainen, In the American Spirit: Folk Art From the Collections (Salem, MA: Peabody Essex Museum, 1994), 33.

36 For more examples and design drawings of this style, see Daniela Mascetti and Amanda Triossi, Earrings: From Antiquity to the Present (London: Thames & Hudson, 1990), 122–23.

37 “Fashions of May,” Peterson’s Magazine: Art, Literature and Fashion, May 1849, 188.