Fabric of a Nation: American Quilt Stories

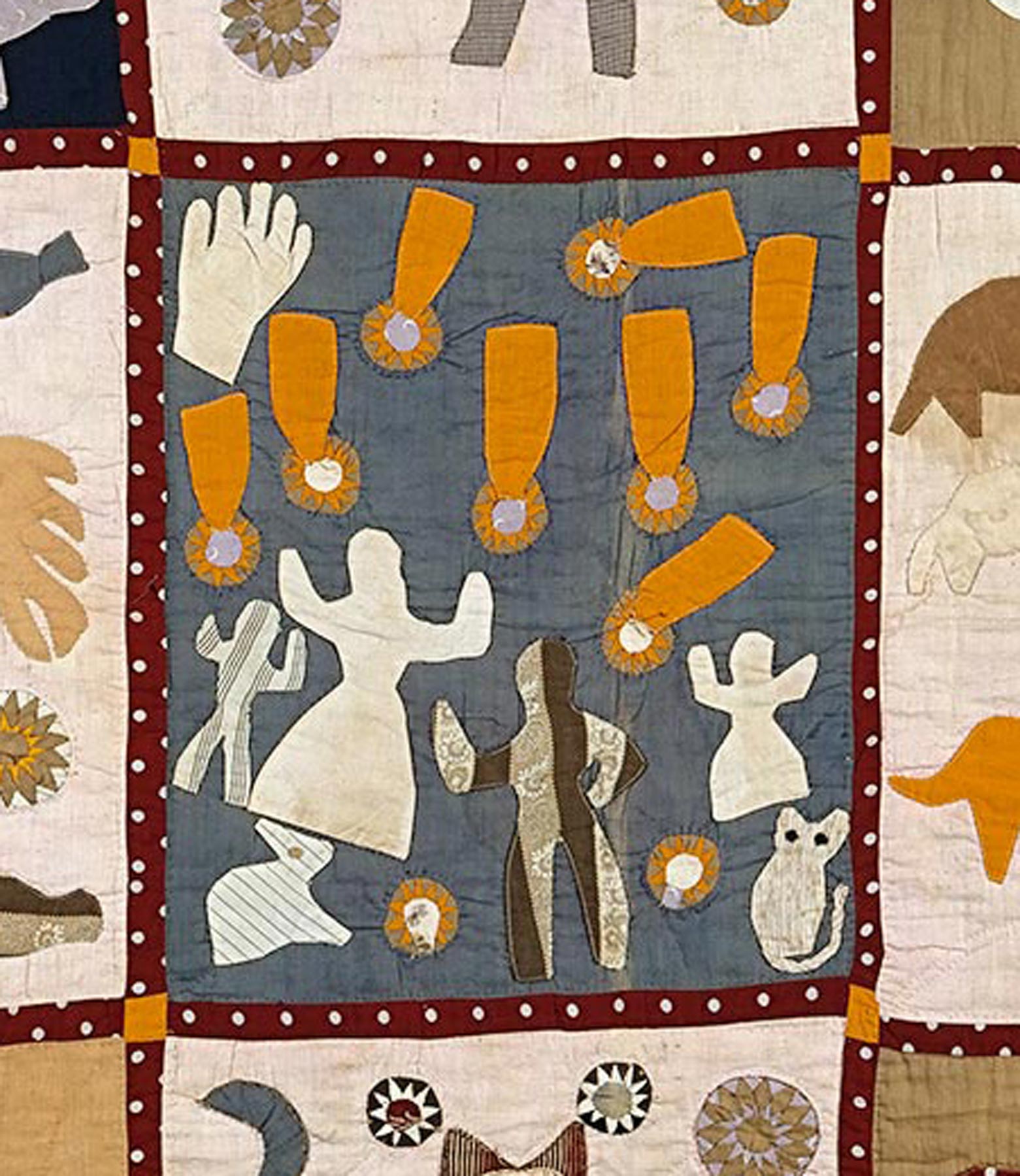

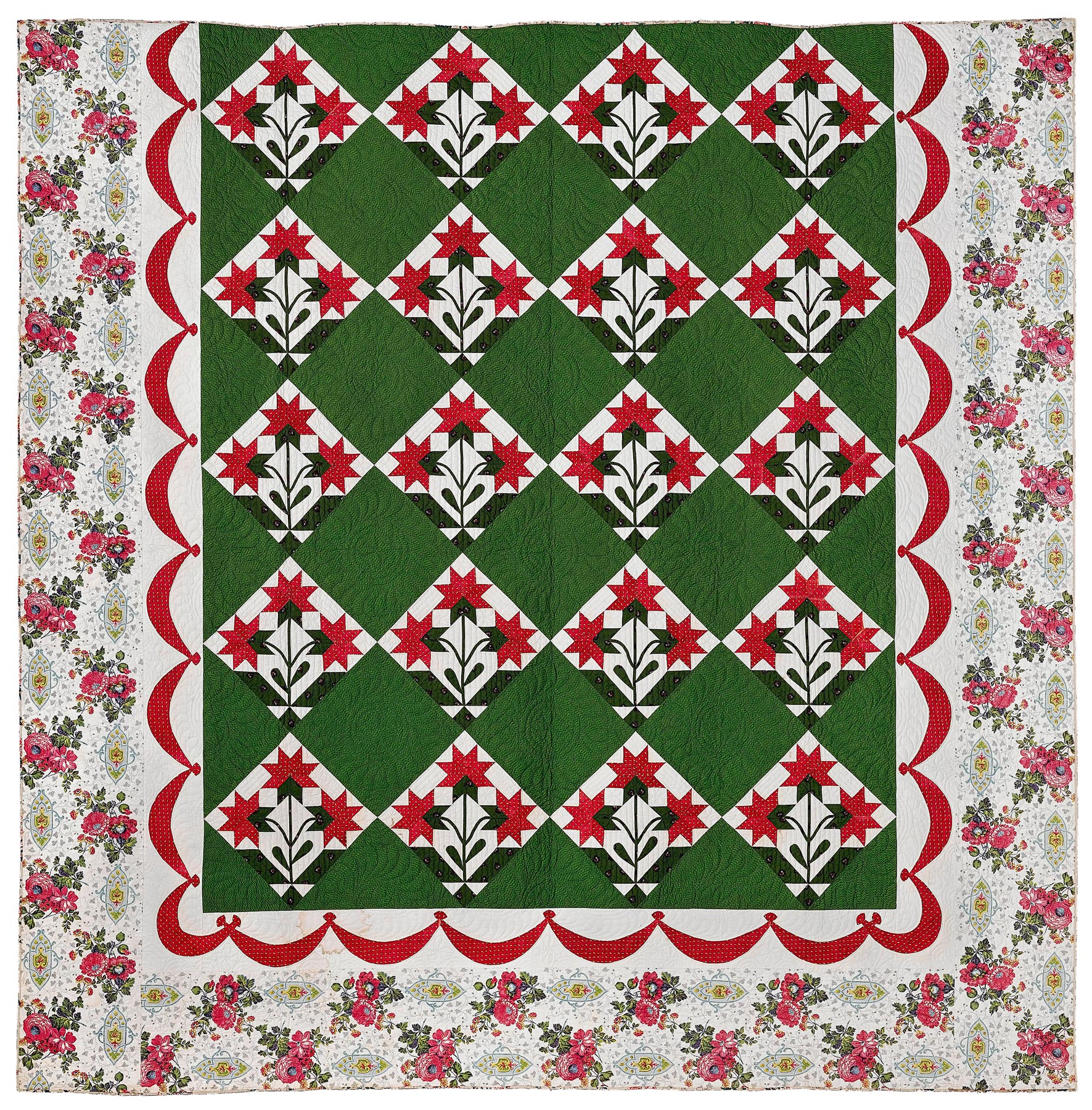

Acknowledging the stories of individuals and communities that have been marginalized, overlooked, or misunderstood is at the heart of Fabric of a Nation: American Quilt Stories. Like the exhibition that is now closed, the publication features important American textiles from the MFA’s collection that span the late seventeenth century to the present day, exploring how these quilts and other bedcovers embody the past while remaining vibrant artforms. The inherently intimate nature of quilts and bedcovers and the strong visual qualities of these works of art invite readers and museum visitors to consider challenging episodes of our nation’s history and the many people and communities who have made America what it is today. Like the exhibition and the collection itself, Fabric of a Nation embraces both the private and public dimensions of American textiles, across the broad expanse of America’s history.

The story of American textiles begins not with white English settlers on the East coast but with early works from the Southwest and centers around an extraordinarily rare colcha or embroidered cover made in the late seventeenth century in a workshop outside of Mexico City in New Spain. (Fig. 1a) Fully covered in a type of long-arm cross stitch also found in contemporary Spanish samplers, repeated figures of lions with pomegranates, leaping stags, and dogs taken from European heraldry are combined with those of four young women shown in the dress of the period.1 (Fig. 1b) Recumbent lambs embroidered throughout the cover likely have Christian significance but also symbolize the sheep and other European domesticated animals that the Spanish brought to the Americas in the early sixteenth century.

The red threads that cover most of the colcha are made from wool dyed with cochineal, a dye made from the larvae of the cochineal beetle that feed on prickly pear cactus. Cultivated on large plantations in the central Mexican region of Oaxaca, cochineal had been used by Indigenous people in Mesoamerica and the Andes for millennia before the arrival of the Spanish. Indigenous labor and knowledge was needed to produce this dye on a large scale in this region of Mexico, an industry that began in the sixteenth-century when the dye became a prized monopoly controlled by the Spanish crown and continued to the mid-nineteenth century, a few decades after Mexico’s independence.

An amalgam of European and Indigenous influences, other aspects of the colchas’s design reflect the pervasive presence of Asian export textiles and other decorative arts in this region of North America. The two white birds in the central field, embroidered between the pairs of lambs, resemble phoenixes found on silk embroidered textiles of the period, which were created in China for export to the Spanish-controlled Philippines. Galleons transported these and other luxury trade goods from Manila to Acapulco on the western coast of Mexico, where they were carried overland to Mexico City and then sent to Havana and eventually Seville from the eastern port of Veracruz. The vases with flowers facing inward from each corner, the scrolling vines interspersed with animal figures, and the overall composition of the outer border with blocked out sections of the inner field are also found on large-scale Asian textiles of the period, from embroidered hangings and covers to woven carpets.2

A century later and nearly 3,000 miles away, Eunice Williams Metcalf (1775–1844) of Lebanon, Connecticut created a bed rugg, most likely just before her marriage to Arunah Metcalf in 1794. (Fig. 2) Embroidered bed ruggs made in New England in the eighteenth century recalled highly prized woven European bed ruggs of the seventeenth and early eighteenth century, which were woven in professional workshops using a complex loop pile structure. Bed ruggs of any manufacture appear in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century American probate inventories much more frequently than quilts. The design of this example is like other bed ruggs embroidered in New London County, Connecticut during the last quarter of the eighteenth century. While made individually at home by sewing rows of running stitches in loops that were cut to create dense pile, their designs follow global patterns established centuries earlier, as seen in this example’s scrolling border with carnation blossoms in the lower corners, which are like the seventeenth-century colcha. Most likely a prized possession, Eunice Williams Metcalf and her new husband took the bed rugg with them when they and several extended family members moved to Cooperstown, New York.3

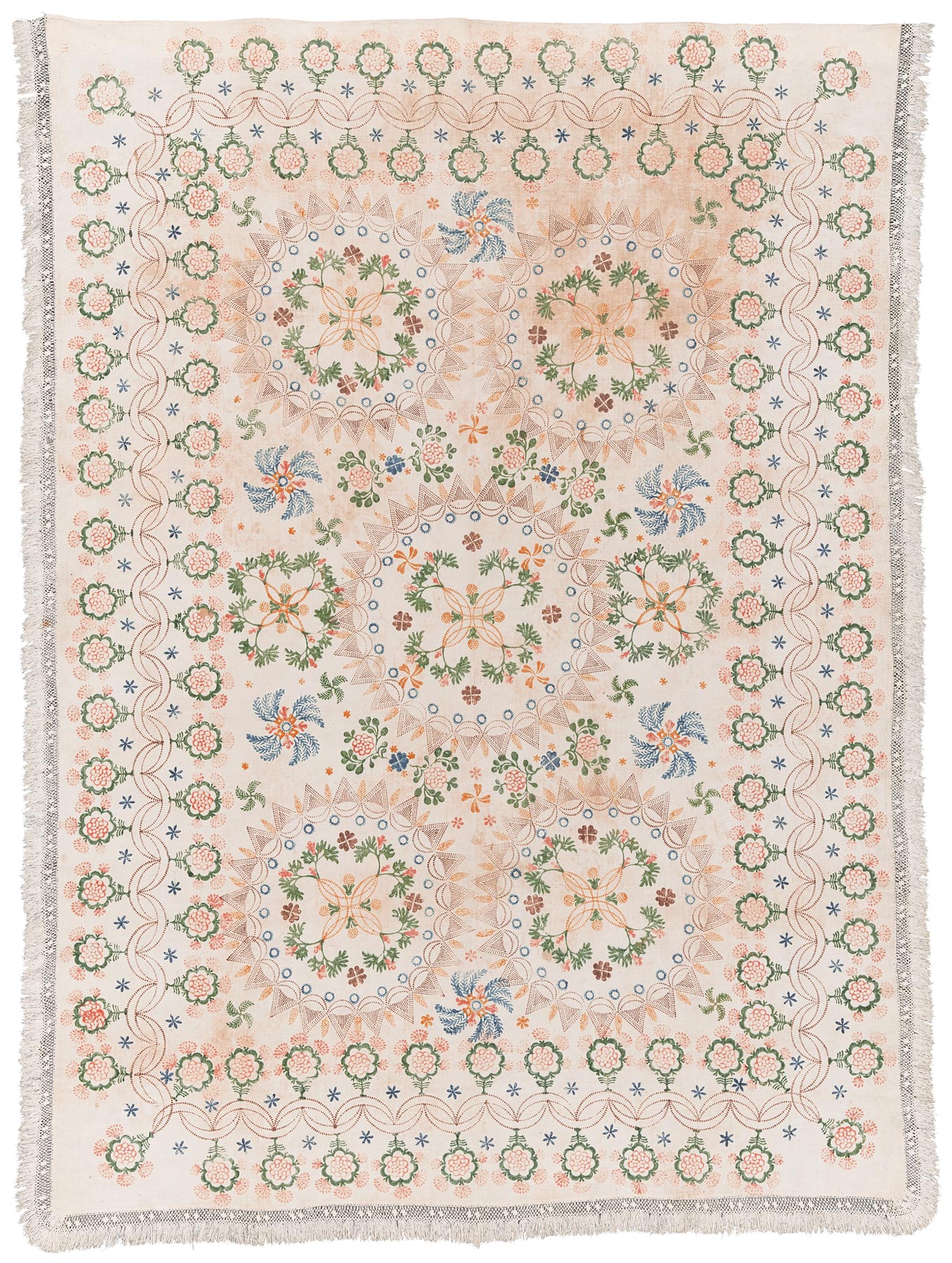

A stamped bedcover owned by Nancy Corbly Clark (1800–1877) of Clermont County, Ohio was also made in a domestic setting. (Fig. 3) Very few stamped American coverlets survive, and most of these include fewer colors and were made a few decades earlier.4 The range of blue, red, green, yellow, and mauve stamped in floral motifs on the finely woven cotton and linen cloth bears resemblance to stenciled and painted textiles made by women at home and girls in female academies in the 1820s and 30s.5 Despite its rarity, a set of now-missing wooden stamps carved to print similar swags, medallions, leaves and blossoms was illustrated in the April 1928 issue of The Magazine Antiques.6 Combining commercially available pigments such as Prussian blue, red ocher, red lead, vermillion, and lead chromate yellow with linseed oil, the stamper created this exuberant pattern of medallions in a floral border with swags, perhaps with the intention of imitating brightly colored printed cottons. While it is unknown if Nancy Corbly Clark embellished this bedcover herself or paid an itinerant linen stamper, she may have sewed the two pieces of white cloth together to make the full width of the bedcover and hand knotted the cotton fringe around the edges to finish it. Like the Metcalf family that moved from eastern Connecticut to upstate New York in the last years of the eighteenth century, Nancy Corbly Clark and her husband, Orson Clark (1792–1864), migrated west from the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia to southern Ohio in a time when areas north and west of the eastern seaboard became available to white settlement soon after displacement of their Indigenous populations.7

Unlike Jonathan Holstein’s Abstract Design in American Quilts thirty years earlier, Bill Arnett and other contributors identified each quiltmaker, placing them within the context of this community while selectively overlooking broader aspects of the makers’ class and race.21 Irene Williams, for example, lived on the outskirts of town in the Rehoboth neighborhood and began making quilts after her marriage with the few materials at hand, instead of learning from aunts and grandmothers as many other Gee’s Bend quilters did. It is not known if Irene Williams joined Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. on his march from Selma to Montgomery on March 21-25, 1966, just nine years before she made this quilt from this red, white and blue VOTE patterned cotton and white and pink solid fabric with pieces checked and blue striped cloth. She most likely saw him speak one evening at Pleasant Grove Baptist Church just a year before this historic march. Inspired by Dr. King Jr.’s words, many in Gee’s Bend crossed the Alabama River to register to vote at the Wilcox County courthouse in Camden, only to have the ferry service terminated soon after. Williams’s quilt speaks to the innumerable obstacles to overcome to assert this most basic right of citizenship.22

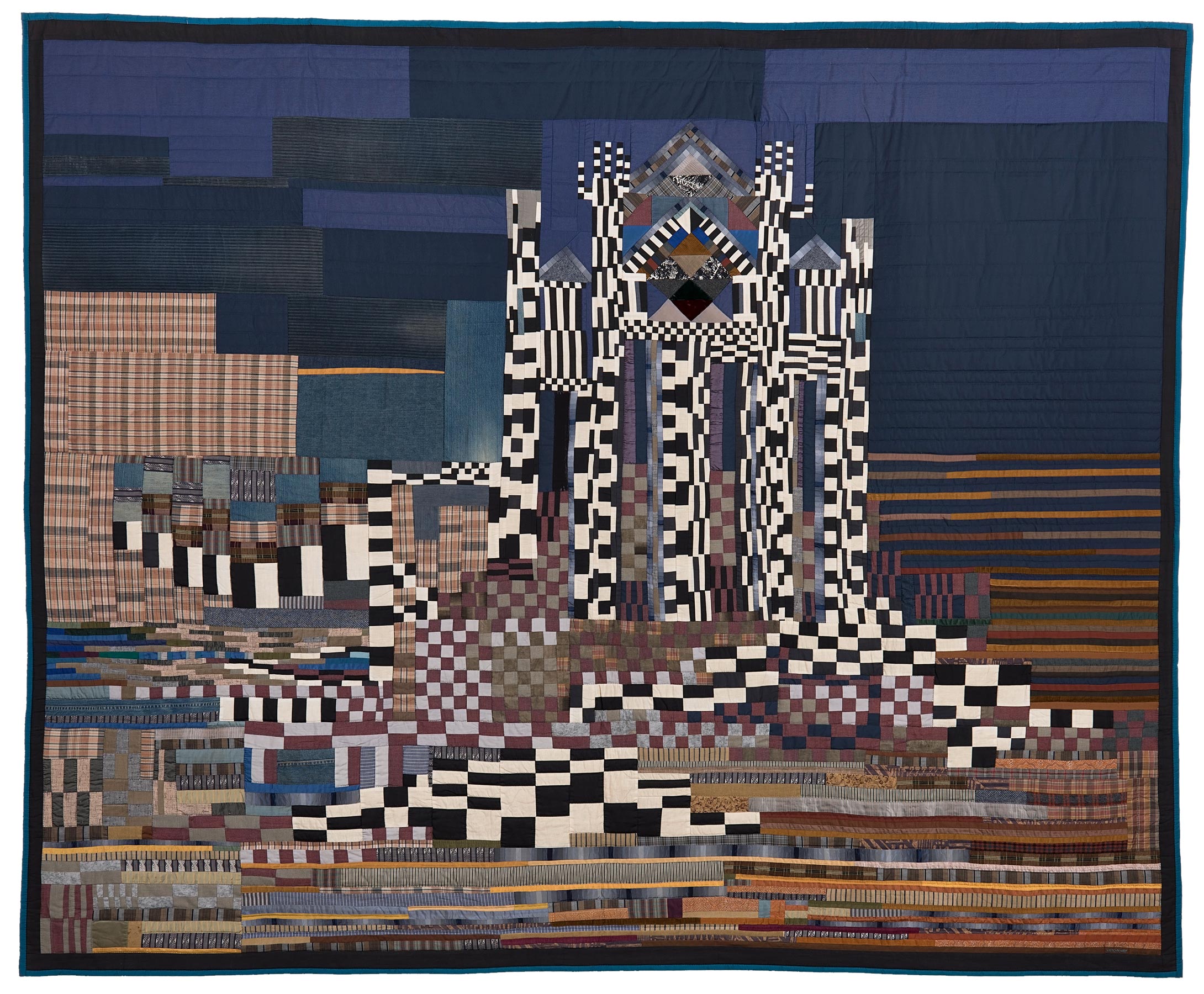

Molly Upton (1953–1977) made Watchtower in the same year that Irene Williams created the Vote quilt in the wake of the civil rights movement, but in anticipation of the Bicentennial. (Fig. 14) In the summer of 1975, Upton set up her studio in Boston City Hall, along with friend and artistic partner Susan Hoffman (b. 1953), after receiving a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts for the Works in Progress project that funded artists working along the city’s Freedom Trail. Work from all ten artists participating in this project was shown at the Boston Center for the Arts in an exhibition organized by the Institute of Contemporary Art. Upton combined a range of textiles to create this imagined architectural structure in black and white pieces of cloth placed in a landscape of subtle earth tones beneath a deep blue sky made from solidly dyed blue cloth and worn blue denim pieces closer to the horizon.23 Upton was in the vanguard of American artists from this period who chose the quilt medium to express their vision, making what have come to be known as ‘art’ quilts, destined for gallery walls.24 In traveling exhibitions of art quilts to Europe and especially Japan, this new generation of quilts functioned as cultural exports.

Fabric of a Nation, and the MFA’s great collection, celebrate the American quilt—a living, vibrant art form—through exceptional objects representing centuries of human creativity and ingenuity. Long admired for their utility, beauty, and design, as well as the sense of community they inspire, quilts have been present in American private and public life for generations. Created by women and men, known individuals and those yet to be identified, urban and rural makers, and members of Black, Latinx, Indigenous, Asian American, and LGBTQIA+ communities, quilts and other bedcovers in the MFA’s collection reflect the diversity of America and the constant renewal of its cultural landscape. As the country has changed, so too has the purpose and meaning of quilts. Early on, quilts, as well as woven blankets, coverlets, and bed ruggs, were appreciated for their warmth and their artistry, as decorative centerpieces in the homes of their makers and those who received them as treasured gifts. By the mid-nineteenth century, quilts were displayed in fairs and other public places, and some makers began to see themselves as textile artists. Today, quilters have expanded the medium to encompass a wide range of techniques, materials, and imagery. Some contemporary artists are using the quilt form to bring attention to social justice issues and to address difficult moments from the nation’s past and present. But all these works share one essential characteristic—an extraordinary power to tell stories, often joyous, sometimes painful, but always unforgettable.

About the Author

Jennifer M. Swope is the David and Roberta Logie Associate Curator of Textile & Fashion Arts at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and a co-curator and co-author of the exhibition and related publication Fabric of a Nation: American Quilt Stories.

1 Terrell Armistead Crow and Mary Moulton Barden, Live Your Own Life: The Family Papers of Mary Bayard Clarke, 1854–1886 (Univ. of South Carolina Press, 2003) as discussed in Brackman, Barbara, Material Culture, Quilt Historian Barbara Brackman’s Blog About Quilts and Fabric, Past and Present

2 Dolores Pfeuffer-Scherer, Remembrance and the American Revolution: Women and the 1876 Centennial Exhibition (Temple Univ., dissertation 2016), pp. 59-61, 82-86, 122-126.

3 Pamela A. Parmal, Jennifer M. Swope, Lauren D. Whitley, Fabric of a Nation: American Quilt Stories (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2021) pp. 18-19

4 Dennis Carr, Made in the Americas (Boston: MFA Publications, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2015)

5 Pamela A. Parmal, Jennifer M. Swope, Lauren D. Whitley, Fabric of a Nation: American Quilt Stories (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2021) pp. 50-51

6 Linda Eaton, Quilts in a Material World (New York: Abrams in association with Henry Francis DuPont Winterthur Museum, 2007), pp. 98-110.

7 Lynne Z. Bassett, “Stenciled Bedcovers,” The Magazine Antiques 163, no. 2 (February 2003): 70-77.

8 Theo Merrill Fisher, “Some Early Pattern Blocks,” The Magazine Antiques 8, no. 4 (April 1928): 285-288.

9 Pamela A. Parmal, Jennifer M. Swope, Lauren D. Whitley, Fabric of a Nation: American Quilt Stories (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2021) pp. 68-71.

10 Sven Beckert, Empire of Cotton, a Global History (New York: Vintage Books, 2014) 205-207, 242-248

11 Pamela A. Parmal, Jennifer M. Swope, Lauren D. Whitley, Fabric of a Nation: American Quilt Stories (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2021) pp. 58-61.

12 Pamela A. Parmal, Jennifer M. Swope, Lauren D. Whitley, Fabric of a Nation: American Quilt Stories (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2021) pp. 76-77.

13 Pamela A. Parmal, Jennifer M. Swope, Lauren D. Whitley, Fabric of a Nation: American Quilt Stories (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2021) pp. 90-91.

14 Kyra Hicks, This I Accomplish (n.p.: Black Threads Press, 2009), p. 4.

15 Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, “A Quilt Unlike Any Other: Rediscovering the Work of Harriet Powers,” in Writing Women’s History: A Tribute To Anne Firor Scott, Chancellor Porter L. Fortune Symposium in Southern History Series, ed. Elizabeth Anne Paine (Jackson, MS: University of Mississippi Press, 2013).

16 Pamela A. Parmal, Jennifer M. Swope, Lauren D. Whitley, Fabric of a Nation: American Quilt Stories (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2021) pp. 124-129.

17 Janneken Smucker, Amish Quilts, Crafting and American Icon (Baltimore, John Hopkins University Press, 2013) pp. ix-xiii.

18 Patricia Mainardi, “Quilts: The Great American Art,” in Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard, eds., Feminism and Art History (New York: Harper & Row, 1982), pp. 331-33, 344. As quoted in Jenni Sorkin’s “Affinities in Abstraction: Textiles, Otherness, and Paining in the 1970s,” in Outliers and American Vanguard Art, by Lynne Coke et al. (Chicago: University Press, 2018) pp. 93-95, 98-102.

19 Janneken Smucker, Amish Quilts, Crafting and American Icon (Baltimore, John Hopkins University Press, 2013) pp. 141-230. Dorothy Osler, Amish Quilts and the Welsh Connection (Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing, 2011), p. 41. Pamela A. Parmal, Jennifer M. Swope, Lauren D. Whitley, Fabric of a Nation: American Quilt Stories (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2021) pp. 98-101.

20 Pamela A. Parmal, Jennifer M. Swope, Lauren D. Whitley, Fabric of a Nation: American Quilt Stories (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2021) pp. 170-172.

21 Bridget R. Cooks, “The Gee’s Bend Effect,” Textile: The Journal of Cloth and Culture 12, no. 3 (2014): 349.

22 Pamela A. Parmal, Jennifer M. Swope, Lauren D. Whitley, Fabric of a Nation: American Quilt Stories (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2021) pp. 178-181.

23 Pamela A. Parmal, Jennifer M. Swope, Lauren D. Whitley, Fabric of a Nation: American Quilt Stories (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2021) pp. 182-189.

24 Robert Shaw, The Art Quilt (New York: Hugh Levin Associates, 1997) pp. 45-77.