Daniel Carl Müller: The Artist as Carousel Carver

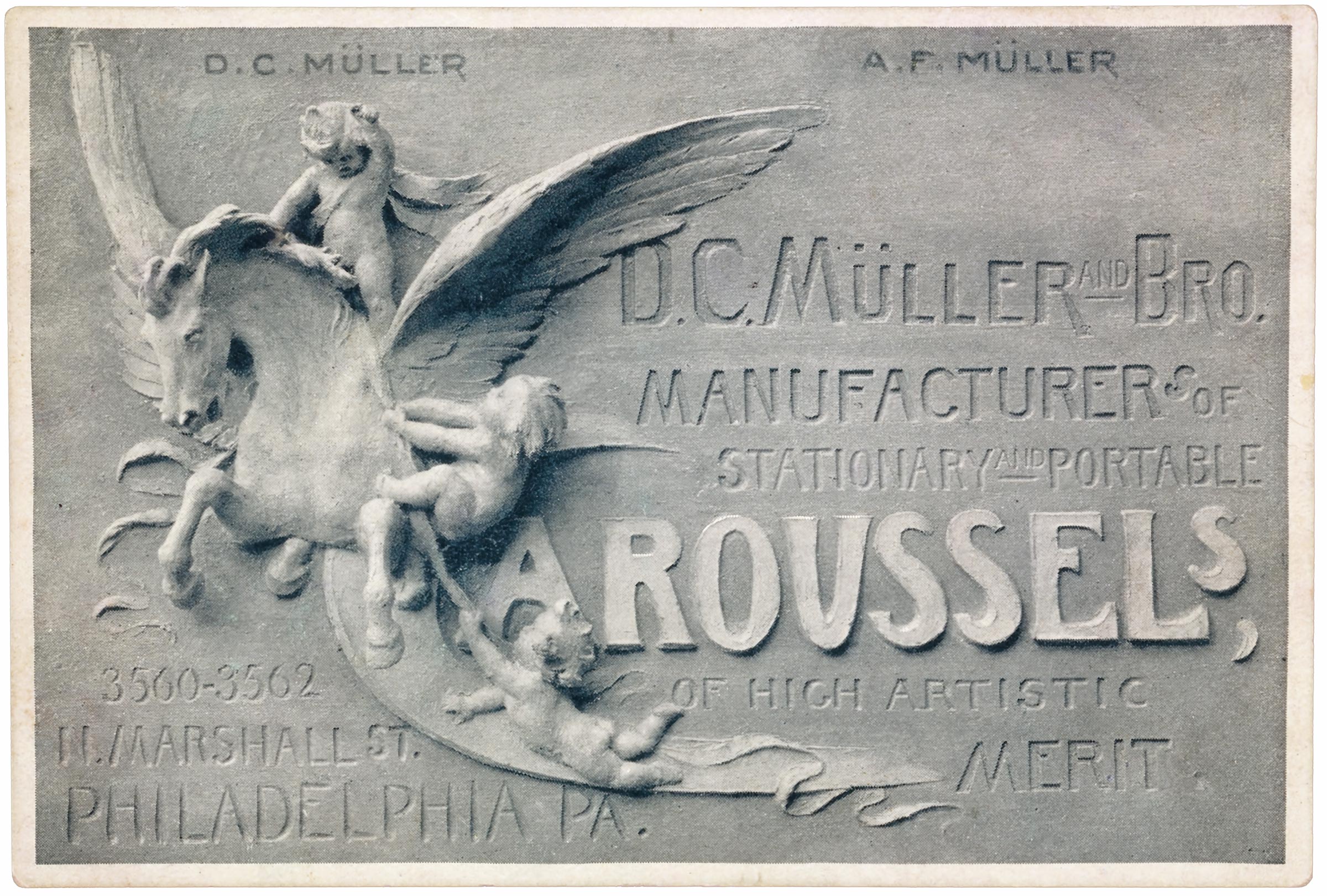

Like many forms of American folk art, the carousel is a European idea brought to the United States. The American carousel was carved into existence by talented immigrant artisans and reached its pinnacle of popularity and artistic achievement in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The life and work of carousel artist Daniel Carl Müller (1872–1952) illuminate the artistic merits of carousels, refute prejudices about commercial art, and demonstrate that definitions of fine and folk art are often circular. Müller was an academically trained sculptor who applied his immense talent to carousel design and carving. Working during the Gilded Age, he was also an aspiring businessman who proudly advertised his company as “Manufacturers of Caroussels [sic] of High Artistic Merit.” Today Müller is widely considered to have been one of the most gifted and important carousel artists, with his figures represented in major museum collections.1 Müller’s story is rooted in the American experience of immigration, entrepreneurship, and individual artistic expression.

Categories

In Wertkin’s book, it becomes apparent that the definition of “folk art” has remained elusive, and many genres of art are placed in this category for no reason other than they don’t seem to fit anywhere else. An issue arises when we note that early carousel figures actually did fit into the traditional definition of folk art. Unfortunately, for many years, carousel carvings from after 1880, regardless of manufacturer, were also placed into this category.

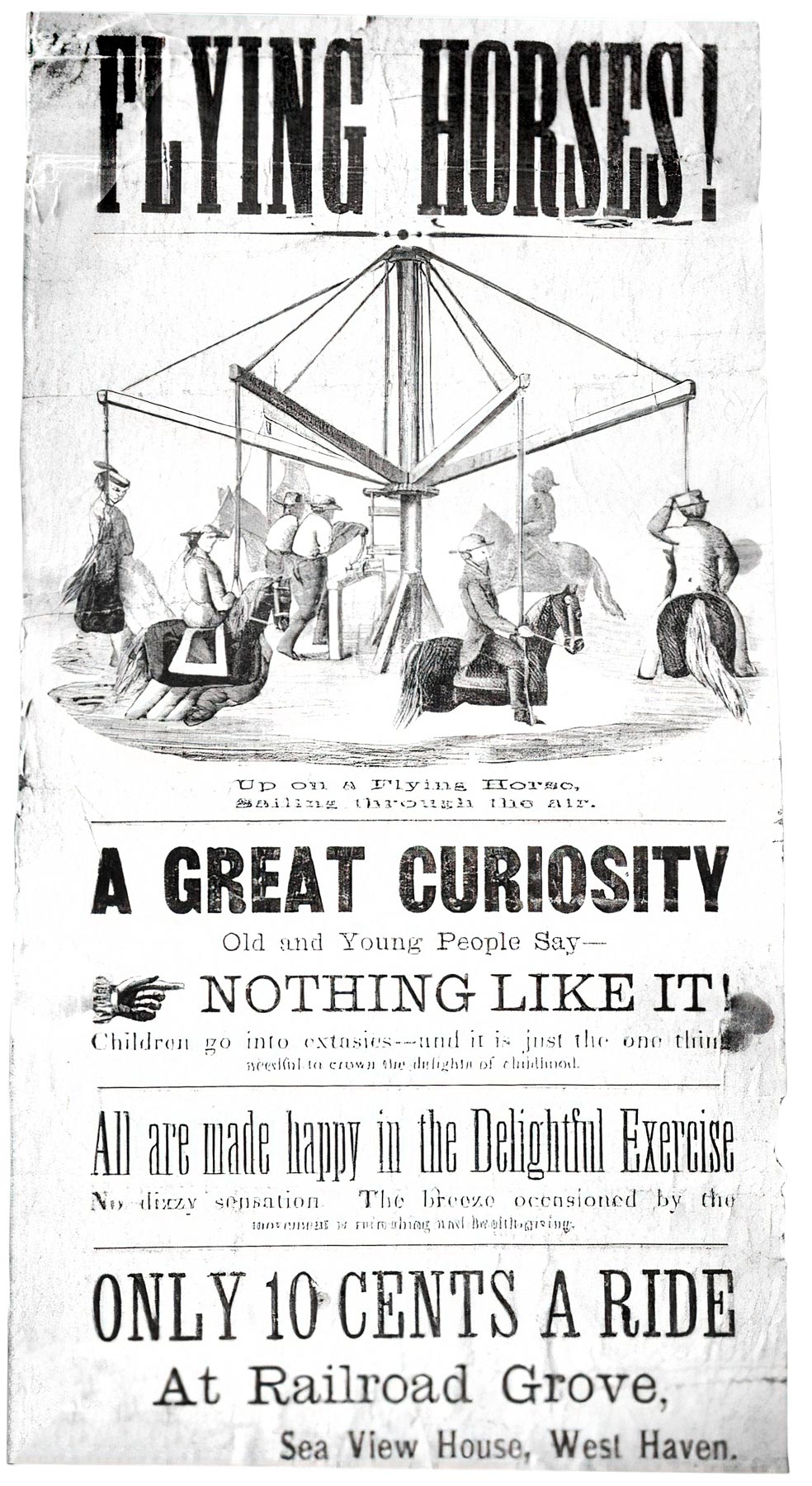

Early American Carousels

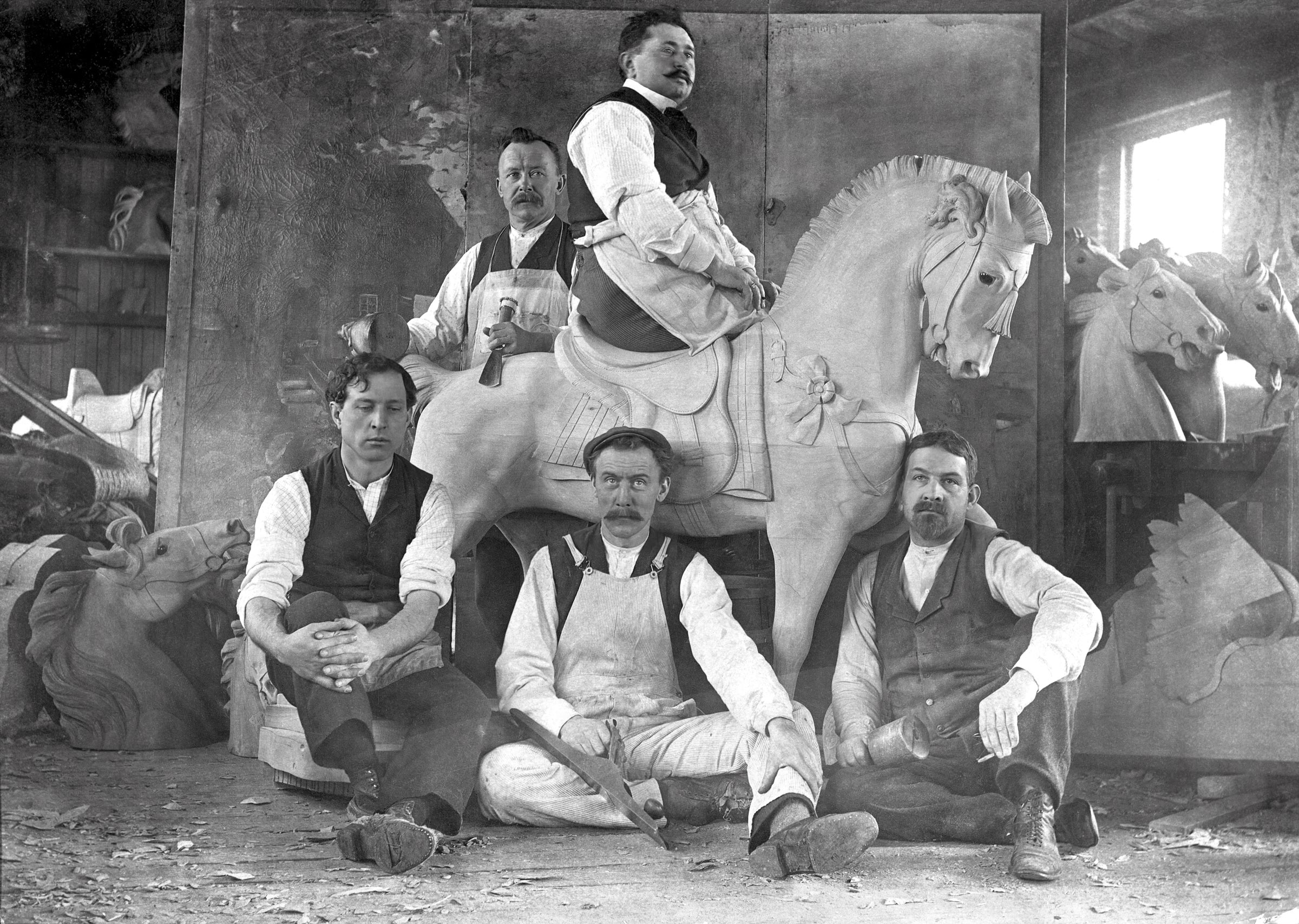

Other makers produced “cookie-cutter” horses, each one nearly identical to the next. Such figures filled a niche for carnivals, which required a machine that could be easily broken down and transported. By 1880, East Coast companies such as Charles W. F. Dare, Norman & Evans, and Armitage Herschell had a steady market for these simpler machines. Their carving shops produced hundreds of similar horses from designed models. Some were made by skilled craftsmen, but this was a form of production-line craft.

In 1864, Gustav Dentzel (1846–1909) immigrated to the United States, bringing pieces of a small carousel he had made with his father in their hometown of Kreuznach, Germany. Dentzel settled in the Germantown neighborhood of Philadelphia, where he opened a cabinetmaking shop and also began fabricating portable carousels for local fairs and parks. In 1870, Charles I. D. Looff (1852–1918), an ambitious metalsmith, also arrived from Germany, settling in Brooklyn, New York. He found work in a furniture factory, and in his spare time pieced together animals from scraps of wood he brought home. In 1876, Looff built one of the first carousels at Coney Island, and during the next forty years he built carousels and other amusement park rides for venues from Bristol, Rhode Island, to Long Beach, California (Fig. 6).

As the field of manufacturers expanded, so did the desire to attract buyers to a higher grade of carousel. By the early 1900s, there were at least eight full-time manufacturers of carousels in the United States, all competing for an expanding market. Trolley companies, both private and municipal, looking for ways to encourage weekend streetcar riding, built small parks for recreation at the ends of lines, often with bandstands, pavilions for picnics, and electric-powered carousels with band organs.9

With the proliferation of such parks, permanent carousels with more ornate and finely carved figures took the place of simpler, portable machines.10

The Craftsman as Fine Artist

In 1880, a friend of Dentzel, Johann Müller, immigrated from Hamburg, Germany, to Gravesend, Brooklyn, with his wife and children.11 The family soon moved to Philadelphia, at the invitation of Dentzel, where Müller worked at his friend’s shop. The Müller children, Daniel and his younger brother, Alfred, also worked at the factory as woodworking apprentices. In 1887, a flu epidemic claimed Müller’s wife, Wilhelmina, and then in December of 1889, Müller died, leaving the two teenage boys orphaned. Dentzel assumed responsibility for their education and training, bringing them under his care and tutelage as apprentices to the master craftsmen in his workshop.

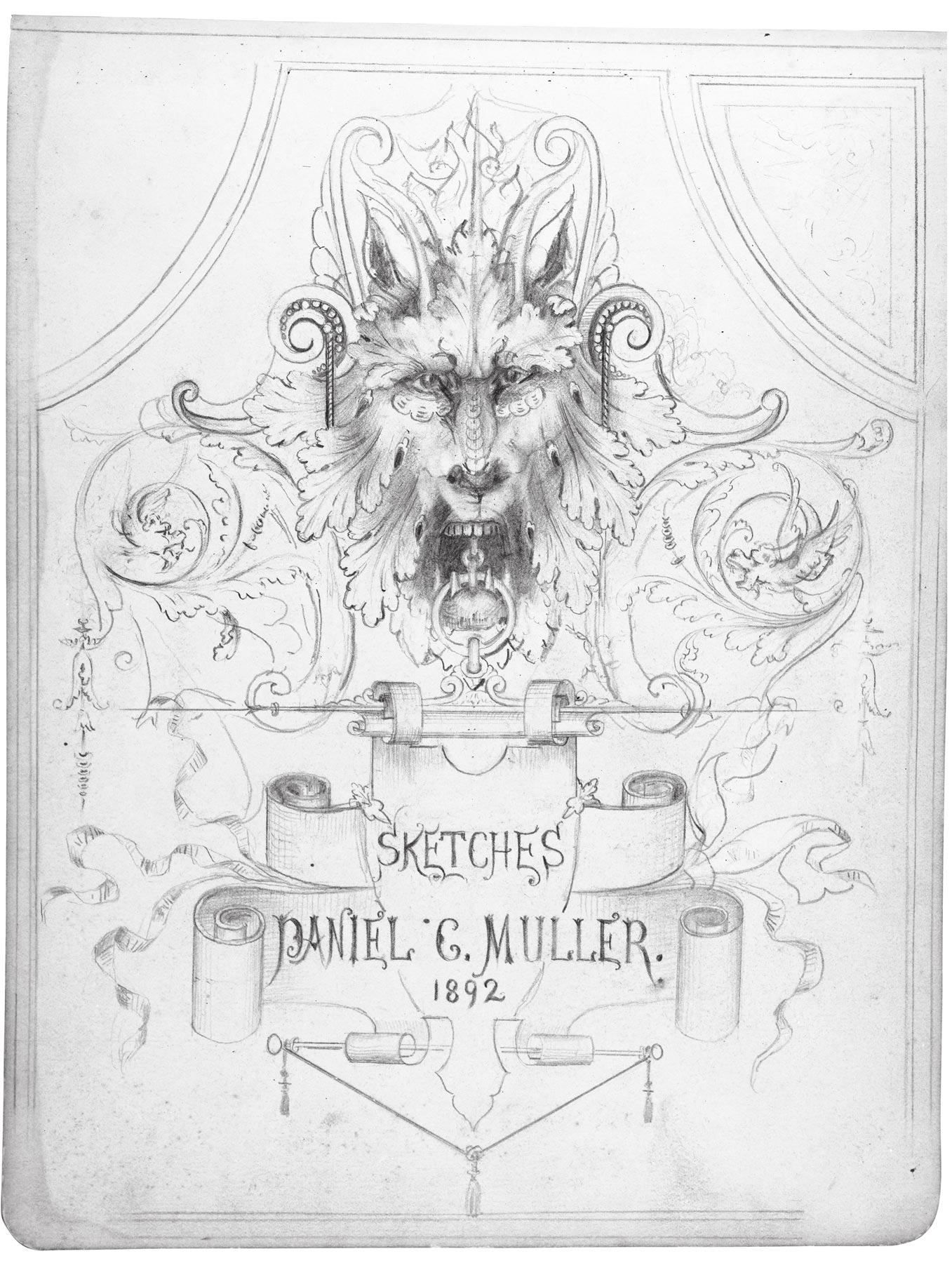

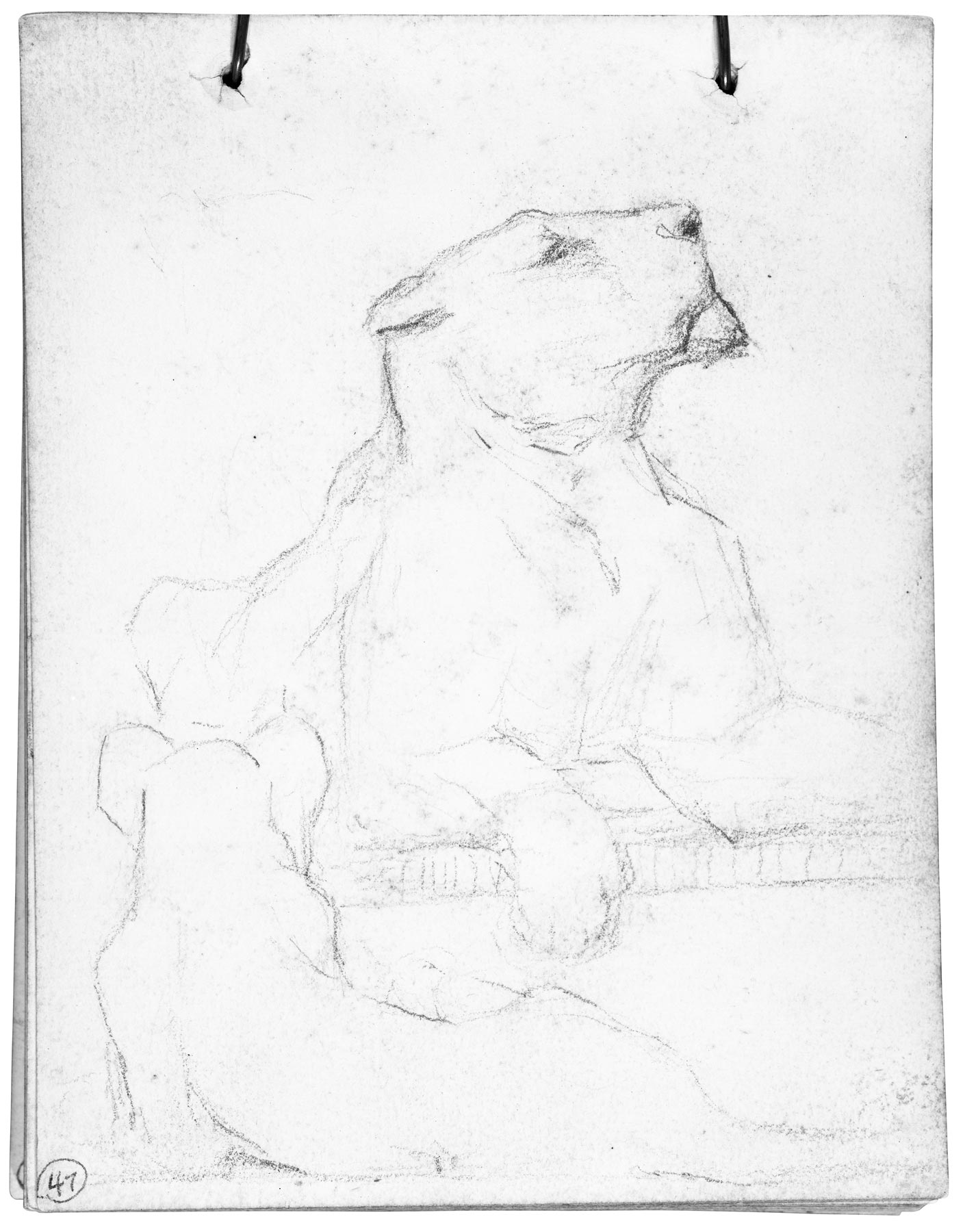

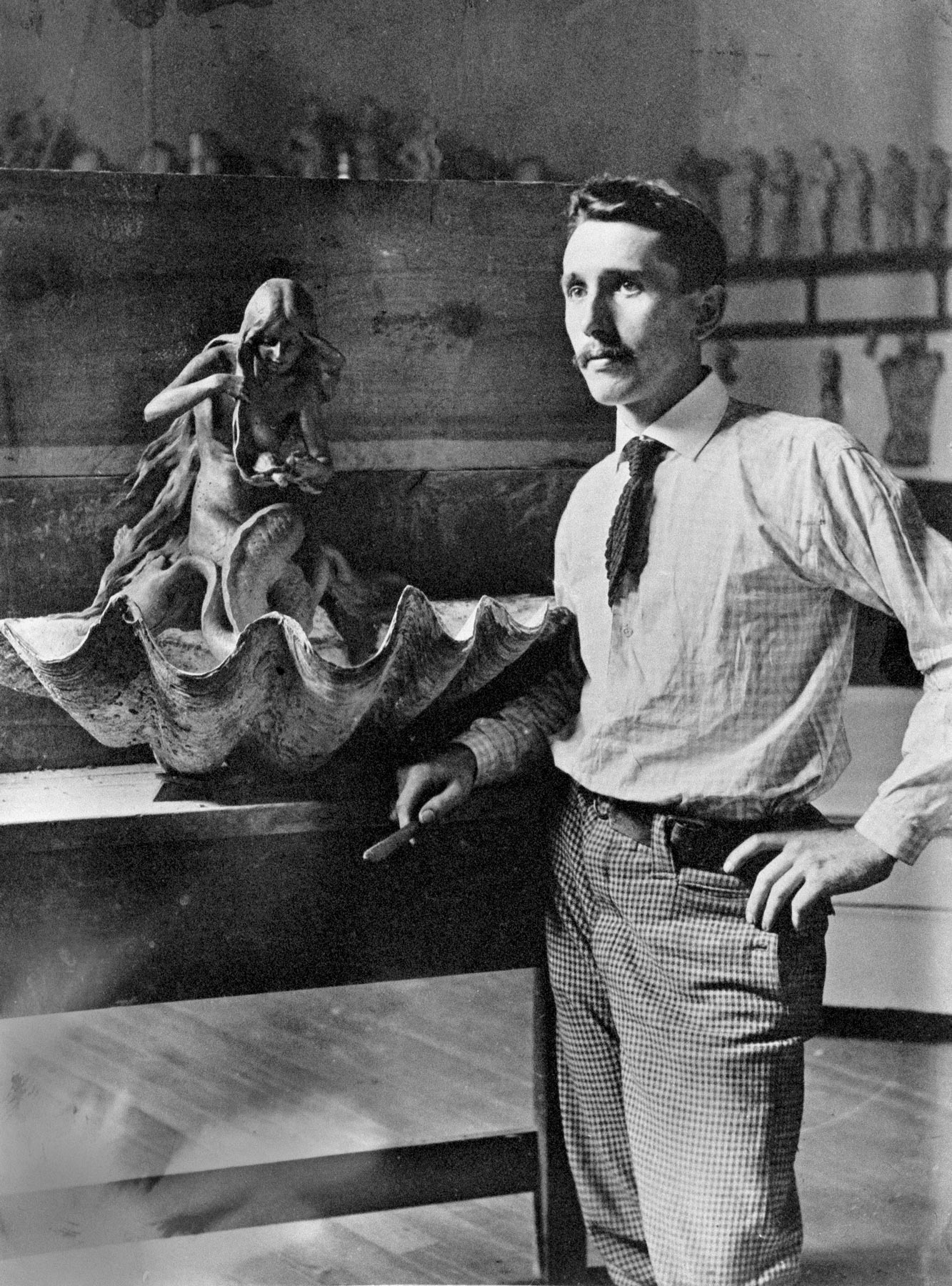

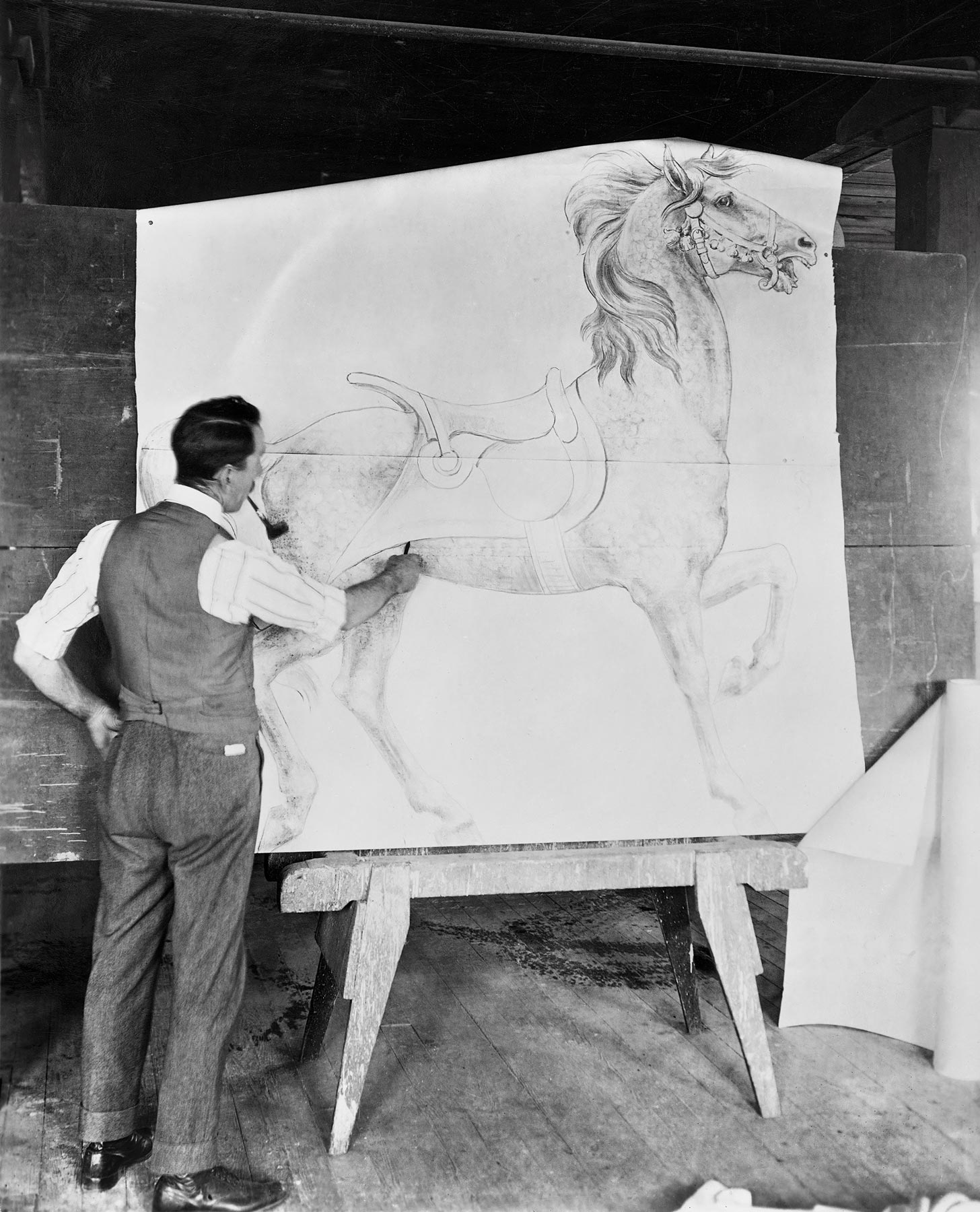

Around the time of his father’s death, Daniel Müller began focusing on his artwork and, according to family oral history, he and his brother enrolled in a local art school. He made frequent Sunday trips to the Philadelphia Zoo to sketch the exotic animals, and his artistic interests began to expand beyond carousel carving (Fig. 10a, 10b). At the age of twenty-four, Müller enrolled in the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA), one of the most prestigious art schools in the country, where he took classes intermittently for the next twelve years and was awarded the Edmund Stewardson prize for sculpture.12 While he continued carving in Dentzel’s shop, Müller also won a competition to design a fountain for the academy. The mermaid-themed fountain was sculpted in 1898, and in 1905 it was cast in bronze and installed in the lobby, where it can still be seen today (Figs. 11a, 11b).

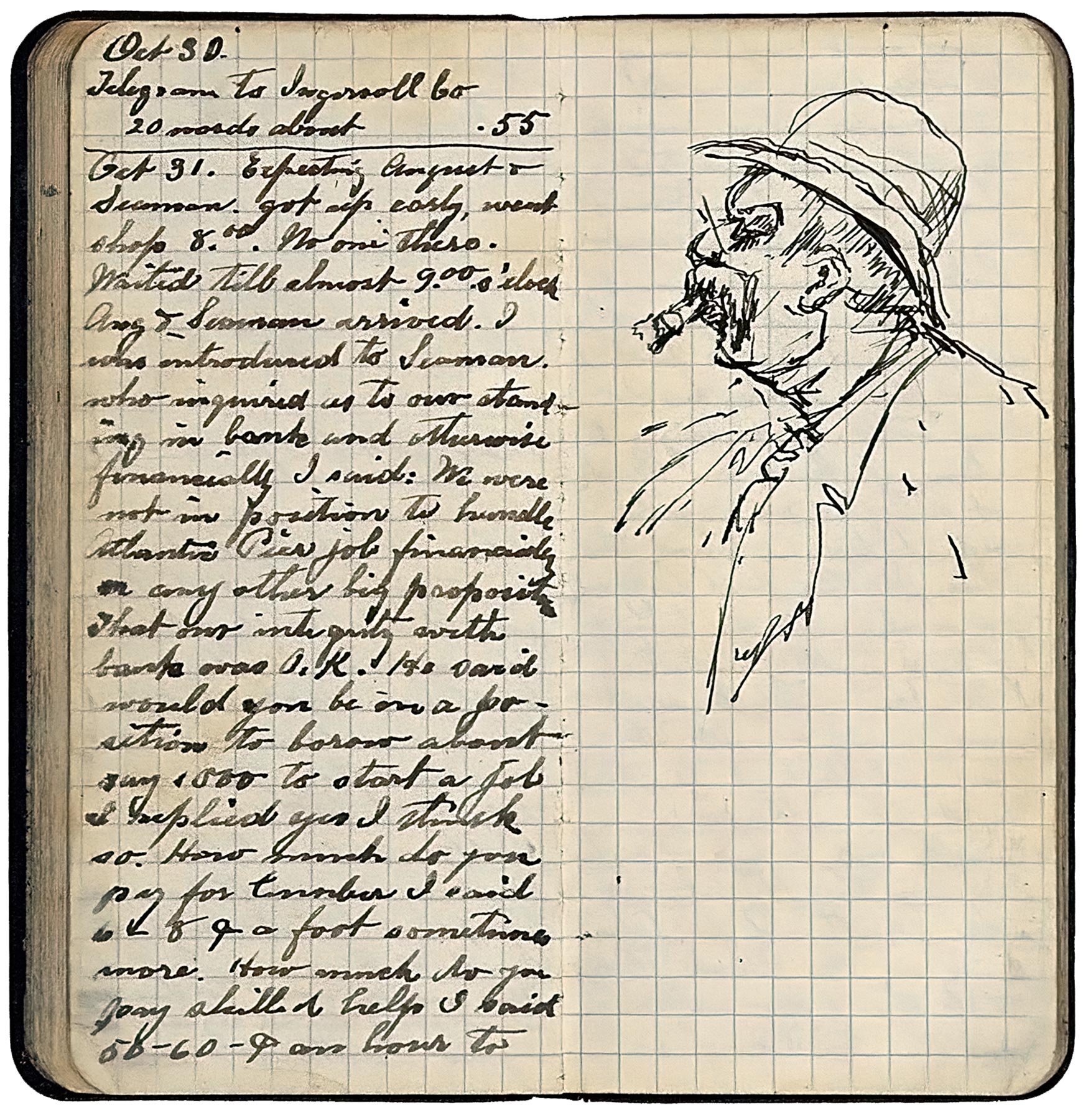

Salisbury and I had [a] conversation as to getting together on the deal. He proposed that we should build [the] machine after [making the] deal… As this would be more or less an experiment the Pier Co. was to pay for the cost of construction entirely [plus] ten percent of the total cost. Of this latter, the Ingersoll Co. was to receive one-half of the ten percent and pay to us a royalty… I said that I thought this would be satisfactory… Salisbury asked me about what it will cost. I said it is very hard to say but I thought it could be done for between 25,000 or 30,000 dollars. But if they wanted some very extra features for decoration, it would cost more.

The Müller brothers received one of their first orders in 1903 when they were contracted by Gordon W. Lillie (1860–1942), known as “Pawnee Bill.” Lillie operated a wild west show and was in the process of upgrading the wagons he used in his circus parades. Most of the newly designed and carved wagons were being produced by the Sebastian Wagon Company and Samuel Robb (1851–1928) in New York City. At the time, Robb was the leading carver of tobacconist, trade, and circus wagon figures in the country. Lillie hired D. C. Müller & Bro. and Dentzel to supplement the carousel work he had hired Robb to complete.

Although Lillie’s order with Müller involved carved wagons rather than carousels, the scope of the contract evinces the reach of his professional reputation.18 Regarding many of the carvings in Pawnee Bill’s Wild West Show, circus historian Fred Dahlinger noted, “If one mentally erased the wheels and under-gears, the bandwagon side looked more like pieces of fine sculptural work suited more for an art gallery than application to a showman’s wagon.”19

At the height of carousel production, in the early 1900s, almost all of the most creative artisans were immigrants, who were highly influenced by the culture of their new American home.20 While historical themes and fantastic creatures were incorporated into many carousel designs, Civil War motifs held a special fascination for Müller. A number of his carousels included horses outfitted with McClellan saddles.21 A Civil War sword, a canteen, a bed roll, and other details found on a Union officer’s mount were also studied and included by Müller (Fig. 16). One of his military style horses was carved as an homage to the Tenth Cavalry, a post–Civil War African American army regiment (Fig. 17).22

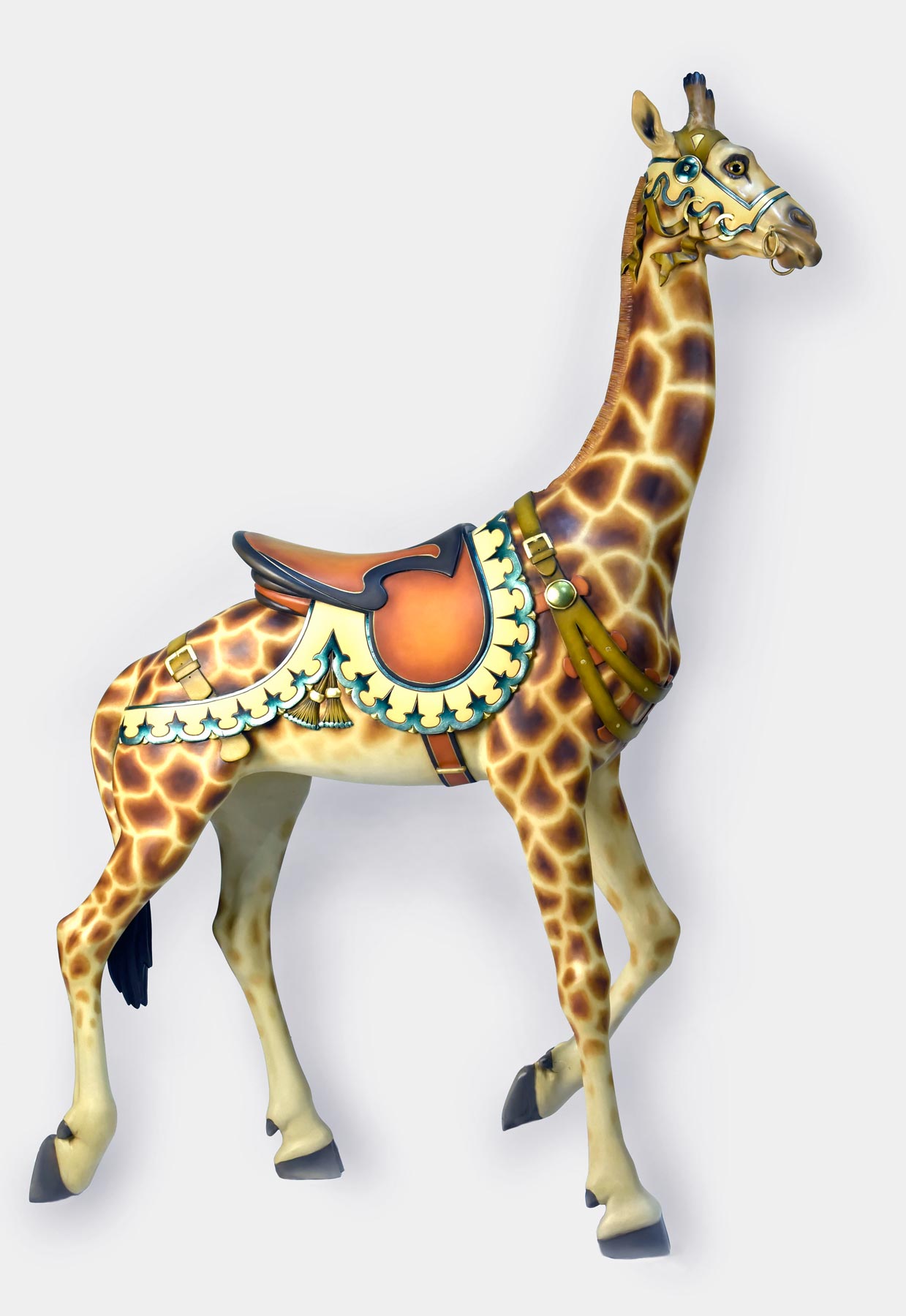

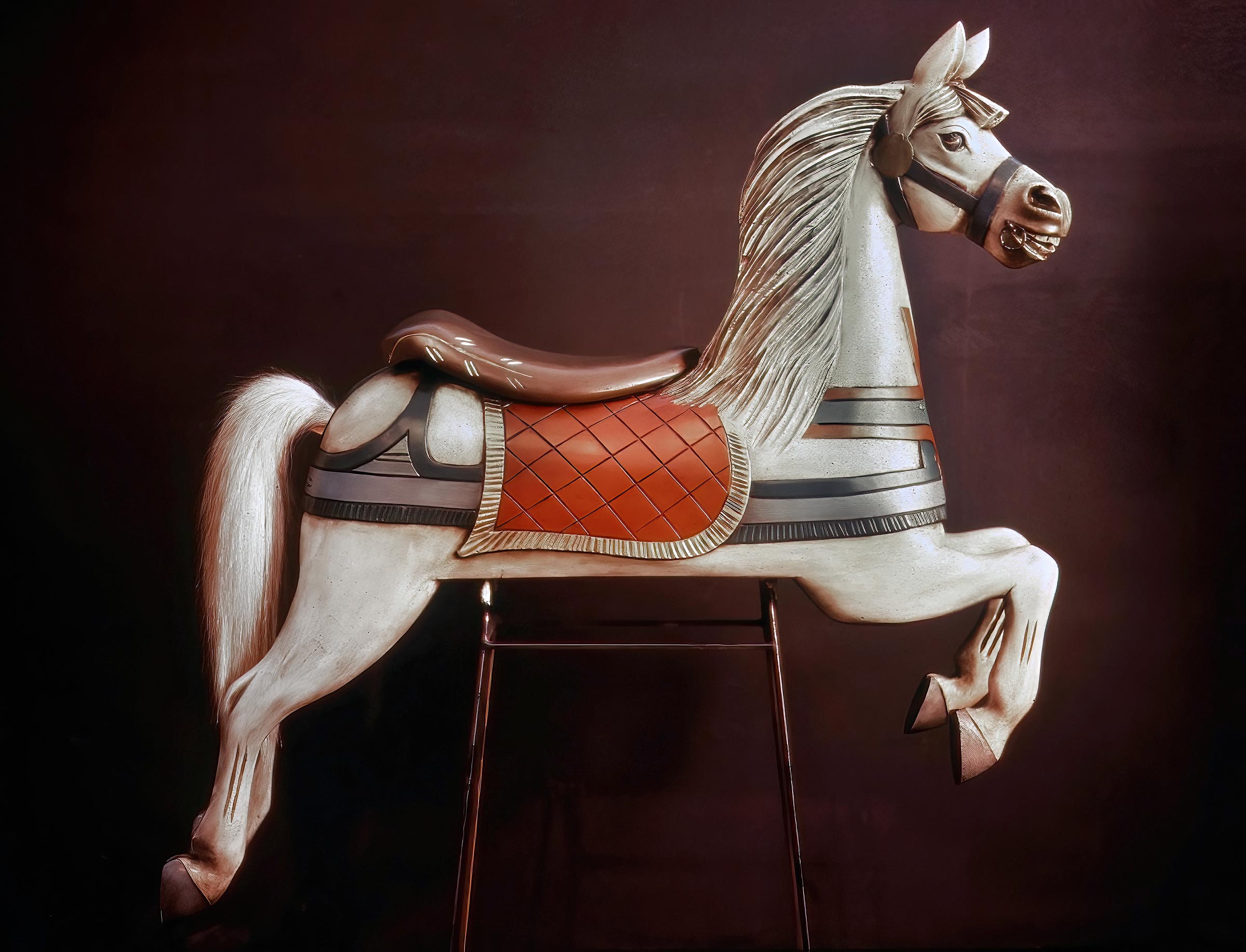

As was the case in Müller’s time, more than a century ago, carousel figures are typically first viewed from a distance. Riders observe the figures and choose the animal that most appeals to their taste. Tickets are purchased, and the riders climb onto the creatures they have selected. The ride lasts about three to four minutes, at which point the riders dismount and proceed to other attractions. The inclusion of intricate detail in the stitching of a saddle, or the particular waves within the carved fabric surely had no bearing on whether someone decided to purchase a ticket. The nuance of muscle tones or the veining on the legs or face of a wooden horse would not increase sales, yet such details were included. Some details of carving were so subtle that they became hidden by the base coat and color overlay, rendered invisible before the figure was ever placed on the machine. One cannot help but wonder what drove a few of these artists to produce carved figures with such exacting detail when it seemed utterly superfluous to the task of completing a utilitarian structure. In the case of Müller, whether he was sculpting in clay at PAFA or carving a wooden carousel figure, he strove to create a work of art and express himself. The beauty and grace of each figure he designed or carved is apparent in each finished piece.

The End of the Golden Age of the Wooden Carousel

The last of the grand wooden carousels was created by the Philadelphia Toboggan Company in 1932. By that time, the country was experiencing the Great Depression, and amusement parks were no longer purchasing elaborate new carousels. The introduction of cast aluminum legs by the Allan Herschell Company, first used on wooden horses made for traveling carnivals, signaled the end of the Golden Age. Metal horses were much more durable and easier to transport than their wooden counterparts. The transition from all wood to metal in the late 1930s also marked the end of Müller’s involvement in the industry.

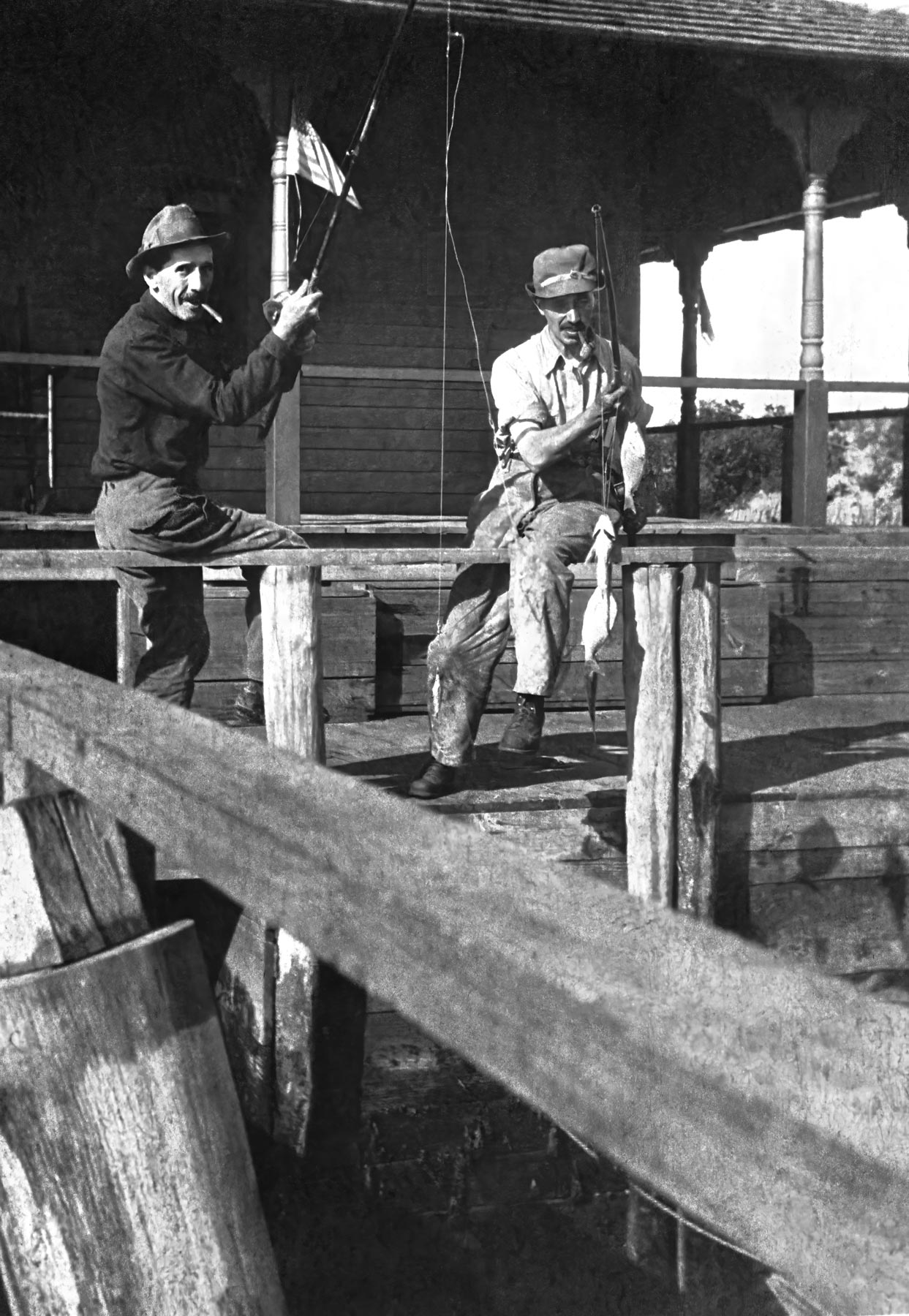

From this point on, Müller resorted to odd jobs and repairing figures on operating machines, while continuing to maintain a partial ownership in a carousel he designed at Palisades Park in New Jersey.23 In his later years, he spent much of his time fishing with his friend Harry Dentzel, Gustav’s nephew, in waters near their homes in New Jersey (Fig. 24).

The Rediscovery of the Wooden Carousel

During the 1970s, about two hundred early wooden carousels remained in operation across the country. Frederick Fried’s 1964 book, A Pictorial History of the Carousel, caught the attention of a growing coterie of early American folk art dealers, collectors, and curators in New York, while a 1972 article on the subject by Barbara Fahs Charles in Smithsonian Magazine reached a broad popular audience.24 Many were beginning to take note of surviving carousels and the finely carved figures that populated them. In 1973, a year after the Smithsonian article, a group of enthusiasts gathered in Sandwich, Massachusetts, to form the National Carousel Roundtable, later renamed the National Carousel Association. It was the beginning of the rediscovery of the work of the master craftsmen.

As awareness of the intrinsic and monetary value of carousel figures increased, philosophical differences developed between those who felt that individual carousel figures would be better preserved in collections and those who wanted to preserve operating machines and maintain their availability to the general public. During the 1970s and 1980s, dozens of rides were broken up and sold at auction, others were purchased as full operating carousels and moved to new locations, such as the Philadelphia Toboggan Company machine that was relocated from Idora Park in Youngstown, Ohio, to the Brooklyn Bridge Park by philanthropic preservationists David and Jane Walentas. However, most of the carousels that went to auction are now exhibited as individual figures in private and museum collections (Fig. 25).

Many of the remaining 120 or so carousels still operating are now championed by local communities, and efforts to keep them intact have greatly reduced the dismantling of these antique machines. At least one of Müller’s carousels has survived and can be seen in Forest Park, Queens, New York (Fig. 26).

Daniel Müller died in 1952, decades before his carousel figures would be displayed in the foremost art museums in his adopted country. Müller exhibited a sculptor’s passion for the visual and tactile, imbuing exacting details within monumental figures. Despite struggling as a businessman, his career represented the intersection of art and enterprise. He worked diligently at balancing these two distinct ambitions at D. C. Müller & Bro., but in the end, he was not able to bridge the gap between creating sculptures and managing a successful business.

Over the past twenty years, new carvers have been creating carousel figures, and dozens of new machines can be found throughout the country. A small number of these carvers have reached a level commensurate with the best of the early makers. These prolific and extremely talented craftspeople have brought back the magic of the hand carved carousel.

Acknowledgments

About the Author

1 Carousel figures by Müller are included in the collections of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, and the Getty Museum in Los Angeles.

2 Carousels have been featured in dozens of films and over 1,500 songs, as well as incorporated into thousands of toys and collectibles. In the beloved 1964 film Mary Poppins, carousels represent childhood fantasy, whereas in Ray Bradbury’s 1962 novel, Something Wicked This Way Comes, they play a darker and even nefarious role. There is the cherished Rodgers and Hammerstein musical and subsequent film Carousel, and they have also been employed as a motif in political parody and in countless advertising campaigns.

3 Gerald C. Wertkin, introduction to Encyclopedia of American Folk Art, ed. Gerald C. Wertkin (New York: Routledge, 2004), xxxii.

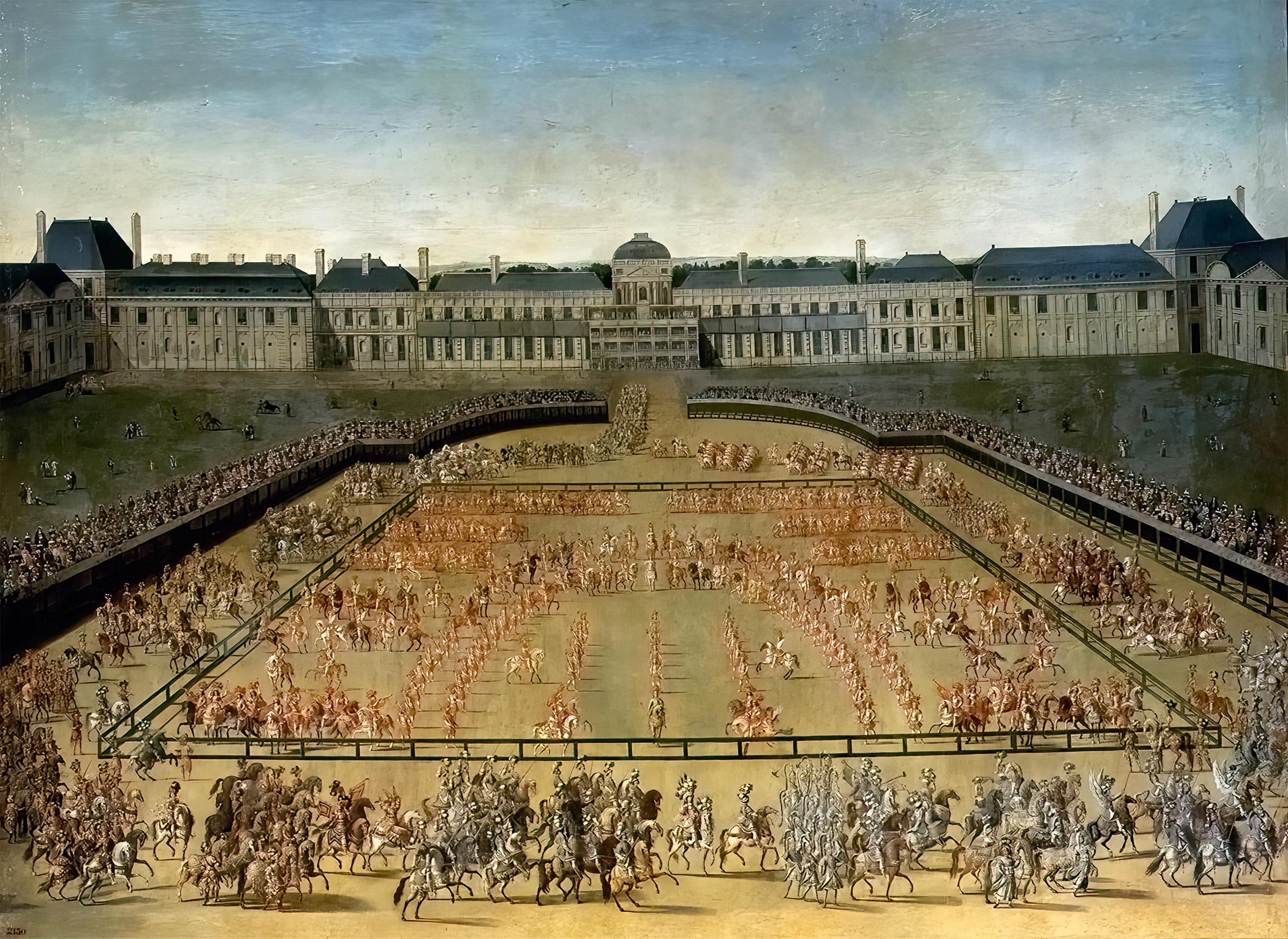

4 The celebration took place just northwest of the Louvre Palace, next to the Tuileries Garden.

5 Most carousels have always spun counterclockwise because this direction allowed riders to reach for suspended rings with their right hands. All American carousels spin in this direction, as do most in Germany and France. For more, see Geoff Weedon, Fairground Art (New York: Abbeville Press, 1981).

6 There is a surviving example of this type in Watch Hill, Rhode Island, which was possibly made in 1867 by Andrew Christian (c. 1825–1876). According to a 2016 article by William Benjamin and Barbara Williams in the Carousel News, Christian manufactured rocking or hobby horses and was known to experiment with other uses for these figures. The Watch Hill horses appear to be very similar to Christian’s work. The Watch Hill carousel is still operating and open to the public. William Benjamin and Barbara Williams, “American Carousel Pioneers: Andrew Christian and Charles Dare,” Carousel News, August 3, 2016.

7 Also spelled Leupold.

8 Charles Leopold is mentioned in several written sources, including a letter from master carver Salvatore Cernigliaro to historian Frederick Fried about Cernigliaro’s time carving for E. Joy Morris (active 1896–1903), prior to moving to Gustav Dentzel’s employ in 1903. Leopold appears in a number of photographs both in the Dentzel shop and in the D. C. Müller & Bro. carving shop. Around 1897, Leopold was hired away from Dentzel to work for the E. Joy Morris Carousel Company. Under Leopold’s guidance, the company began to offer the most ornate and highly detailed carousel figures to come out of any shop.

9 Music was a large part of the experience of riding a carousel. Initially, with the early simple machines, a group of musicians played in the middle of the carousel or just nearby. By 1880, band organs were incorporated into each carousel, providing louder and varied music. Some of these band organs contained dozens of pipes, drums, triangles, and horns. Many of the band organs were made in Germany, France, and Belgium, but like the carousels, companies such as Wurlitzer, B.A.B., and Artizan began manufacturing them in the United States. For most band organs, the music was produced in much the same way as a player piano, with a paper roll dotted with holes that would slide over a vacuum “reader,” sending bursts of air to the instruments built into the organ. The rolls contained dozens of songs and marches and would usually rewind automatically upon reaching the end of their repertoire.

10 Permanent location machines were meant to be set up at a single location and used either year-round or closed temporarily for the winter season. These were generally larger carousels with more animals.

11 According to his death certificate, Johann Müller changed his name to John Miller. Daniel, however, chose to retain the German spelling and pronunciation.

12 The founder of PAFA was another “artist in wood,” William Rush (1756–1832), who achieved success as a neoclassical sculptor during the early years of the republic.

13 PAFA’s biography of Charles Grafly (1862–1929) notes that he was an exceptional sculptor of international repute. He began teaching sculpting at PAFA in 1896, just prior to Müller’s enrollment at the school, and was there until his death. Grafly’s admiration for Müller was such that he sculpted a bust of Müller that still resides at PAFA.

14 During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, there was no standard spelling of the word carousel, which led to names such as carry-us-all, karousel, carroussell, and caroussel.

15 Müller and his wife Elizabeth Muhe Müller (1875–1914) had five children: Alfred Timothy Müller (b. 1897), Carl Daniel Müller (b. 1899), Jonas Grafly Müller (b. 1902), Evelyn Müller (Johnson) (b. 1911), and Louis Müller (b. 1913).

16 Between 1905 and 1915, there were approximately twelve companies producing carousels in America, many of these were of quality, so the competition for sales was intense.

17 In 2005, Brian and Elinor Morgan transcribed all 120 pages of the Müller logbooks that were still in the possession of Evelyn Muller Johnson, his fourth child. Müller kept these logs from the beginning of his company until 1917 when the business closed. Unfortunately, several of the years are missing, but most were kept by his family.

18 It is not known how many wagon tableaux were produced in the Müller shop. A photograph of a wild west themed scene has survived in the Müller family archives.

19 Fred Dahlinger, Jr., “The Grand Parade of Pawnee Bill's Wild West,” Bandwagon: The Journal of the Circus Historical Society, 49, no. 1 (2005): 7.

20 Ellis Island, which opened on January 1, 1892, processed 1.25 million immigrants in 1907, its peak year.

21 General George McClellan (1826–1885) was not considered a particularly good military strategist and was blamed by some for extending the Civil War through his inaction during several early battles. But as a captain in the army, McClellan did contribute to the U.S. Cavalry by helping to procure a practical saddle based partially on observations of military accessories during an 1857 visit to Europe. This saddle design was used by the cavalry for decades and is still in production today.

22 The Tenth Cavalry regiment was formed just after the Civil War. They were best known for their bravery and tenacity fighting the Plains Indians, but the unit remained known as the “Buffalo Soldiers” until the end of segregation in the military, after World War II. Müller’s tribute to the regiment has “10” carved on the saddle.

23 There is little information on Alfred Müller during this period.

24 Frederick Fried, A Pictorial History of the Carousel (New York: Bonanza, 1964); Barbara Fahs Charles, “Merry-Go-Rounds,” Smithsonian, July 1972, 40–47.

25 Examples of this approach are found on the Glen Echo Dentzel carousel in Glen Echo, Maryland, restored over a ten-year period by artist and conservationist Rosa Patton, and the Dentzel machine in Pen Argyl, Pennsylvania, brought back to original paint by restorer Lisa Parr.

26 The original surfaces of most carousel figures were covered by multiple layers of paint over time as they were weathered and worn in use; these subsequent layers are referred to as “park paint.” When carousel companies were still in operation, factories sometimes repainted figures as part of refurbishments. This is referred to today as “factory paint,” and it was almost always superior to the workmanship of park paint.