The Family Record Tradition and The Heart and Hand Artist

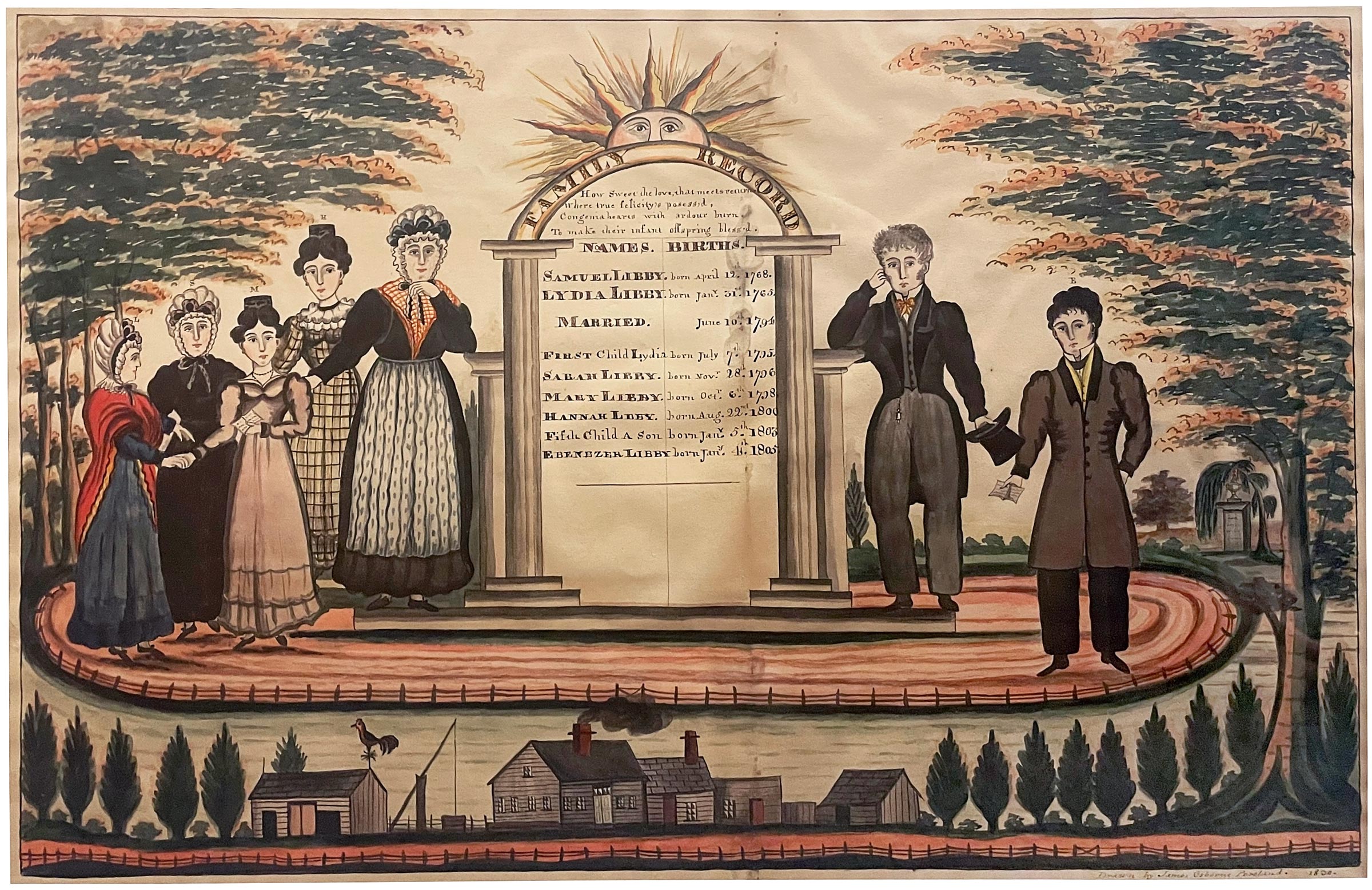

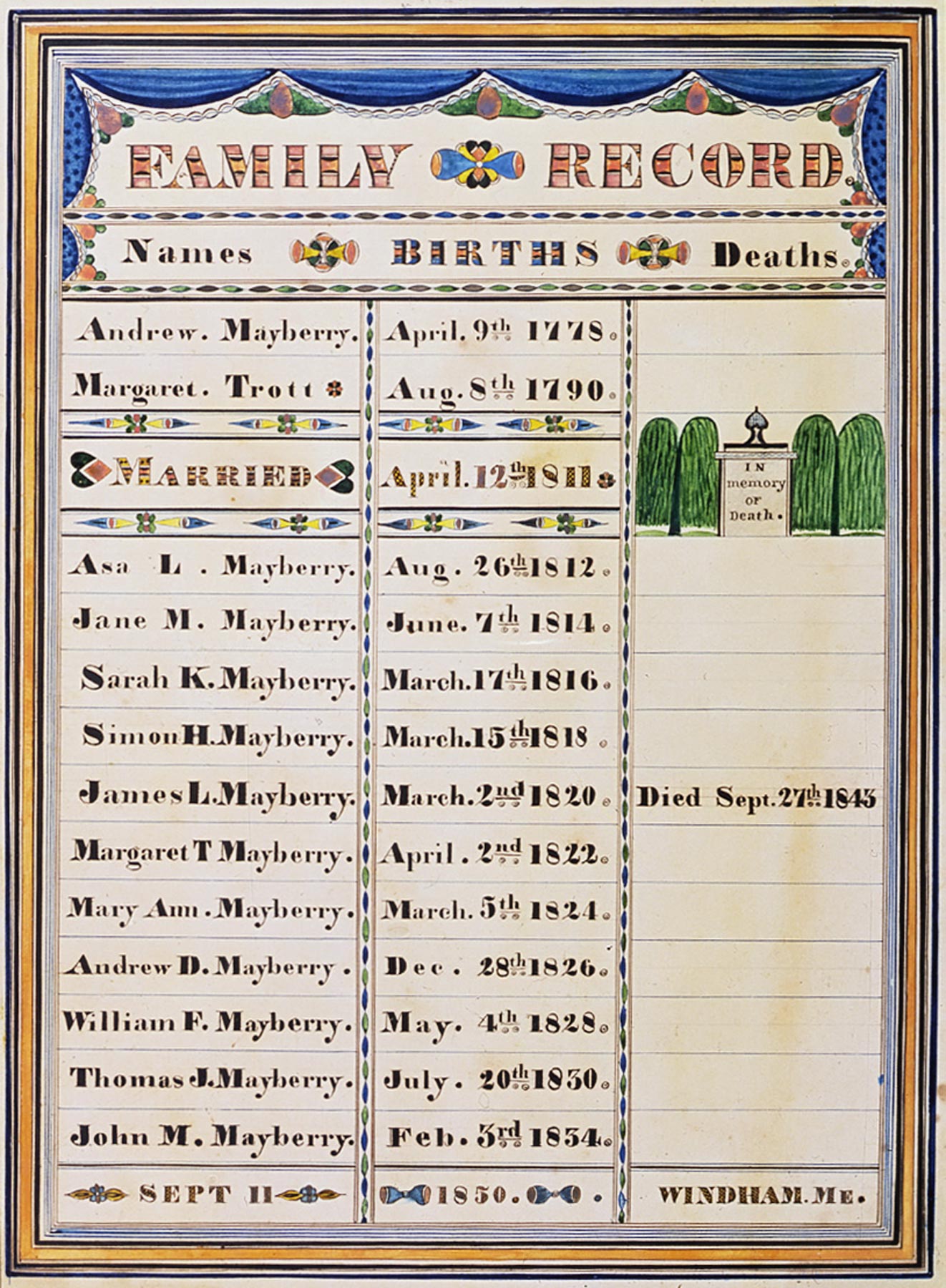

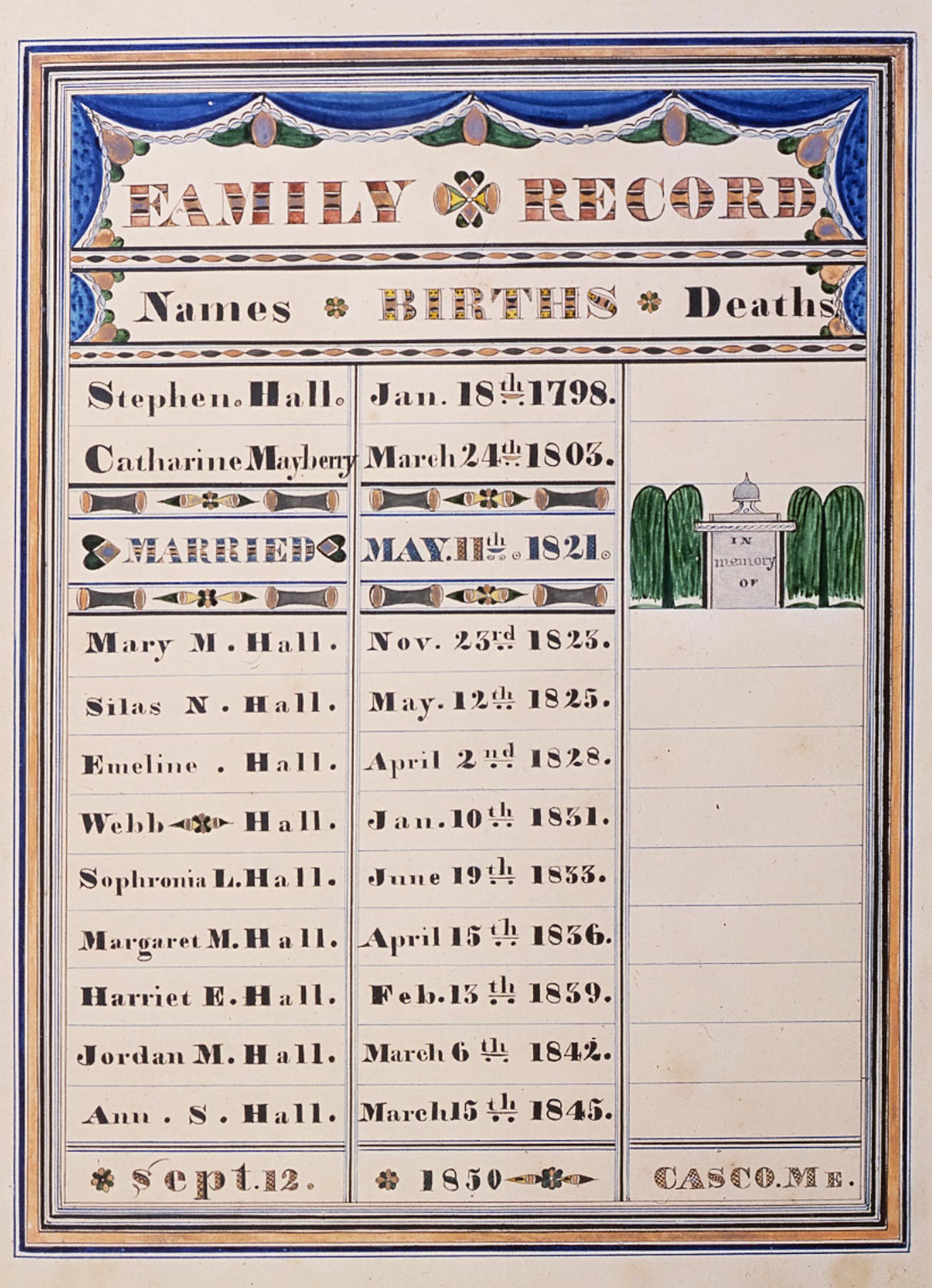

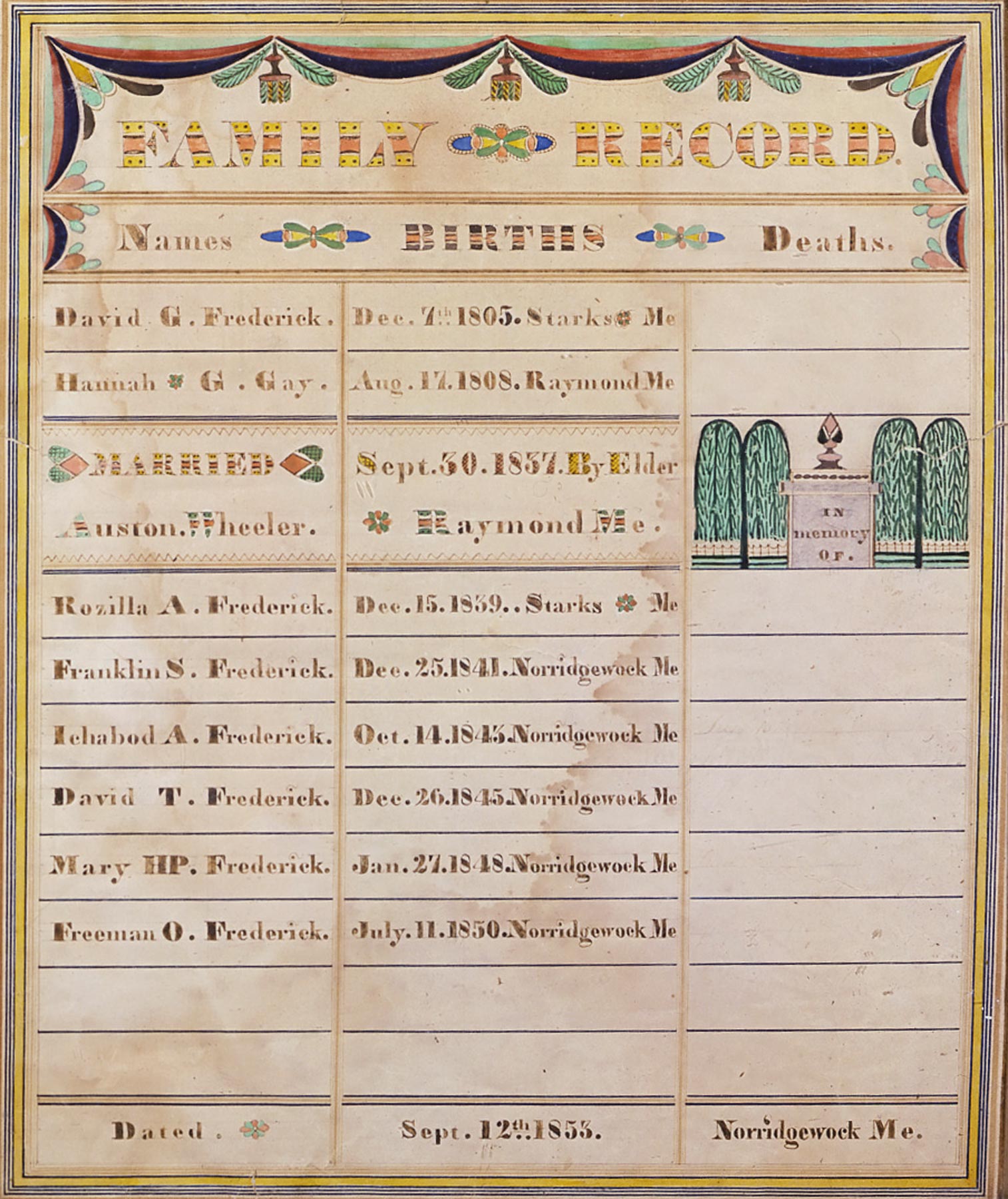

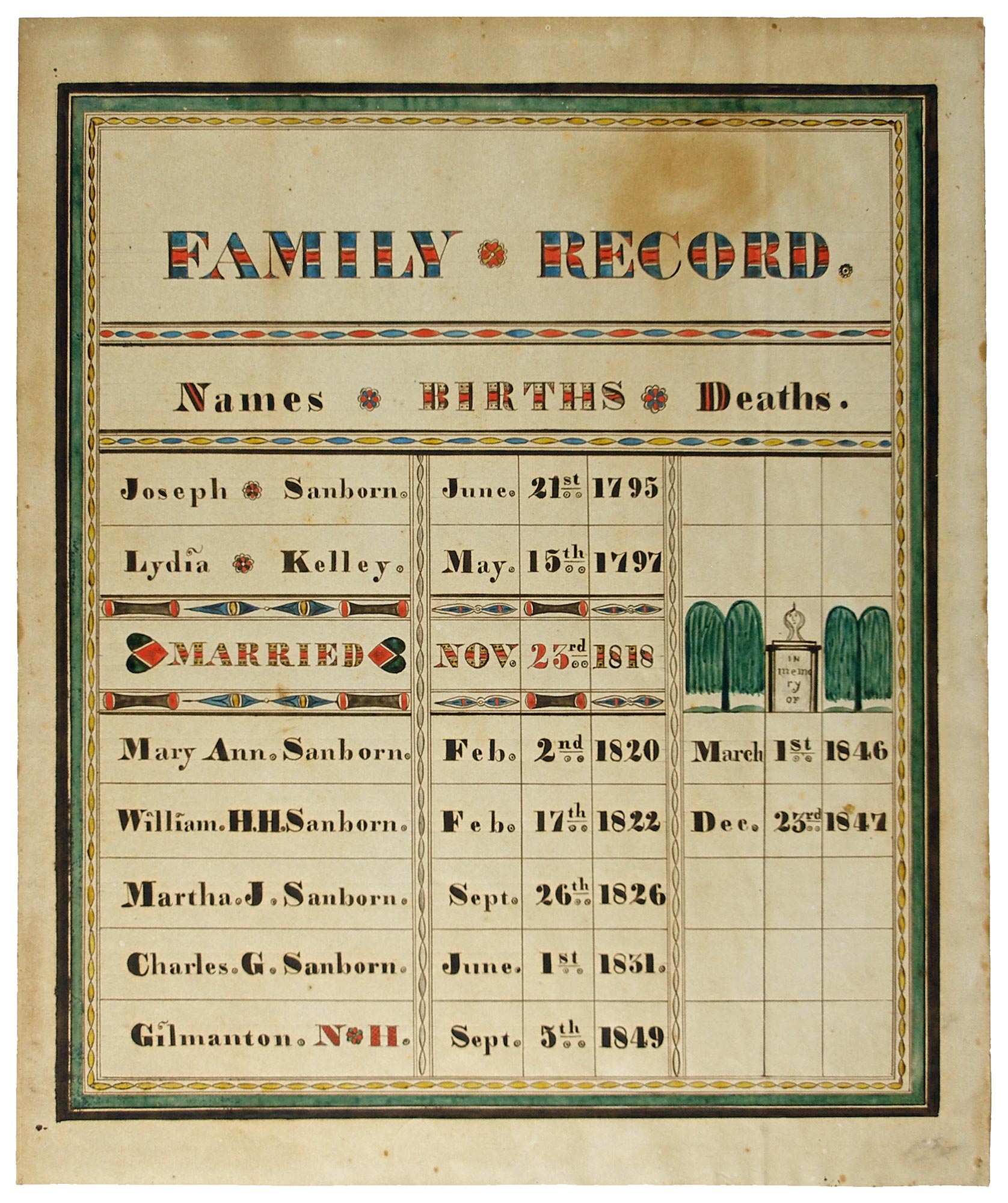

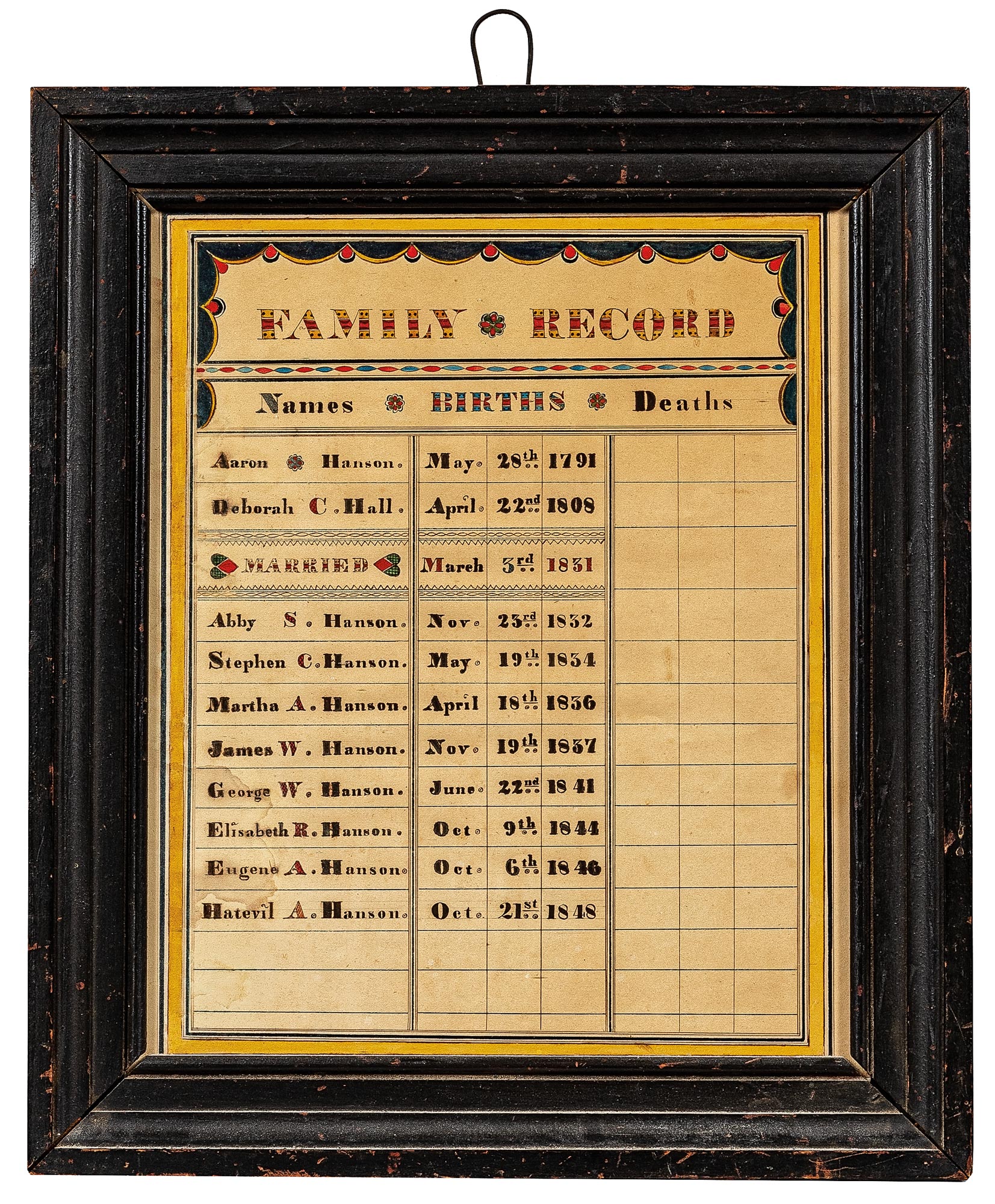

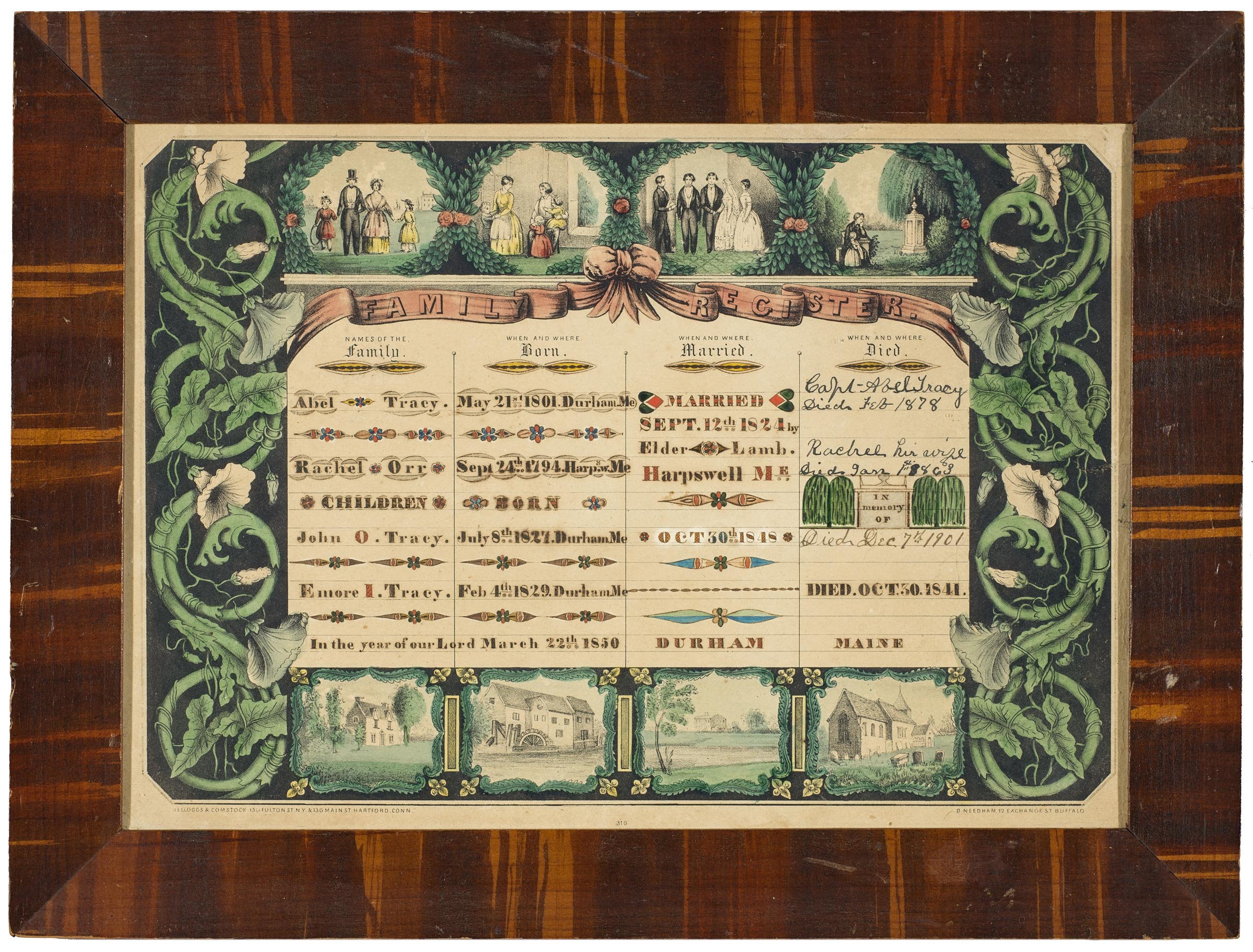

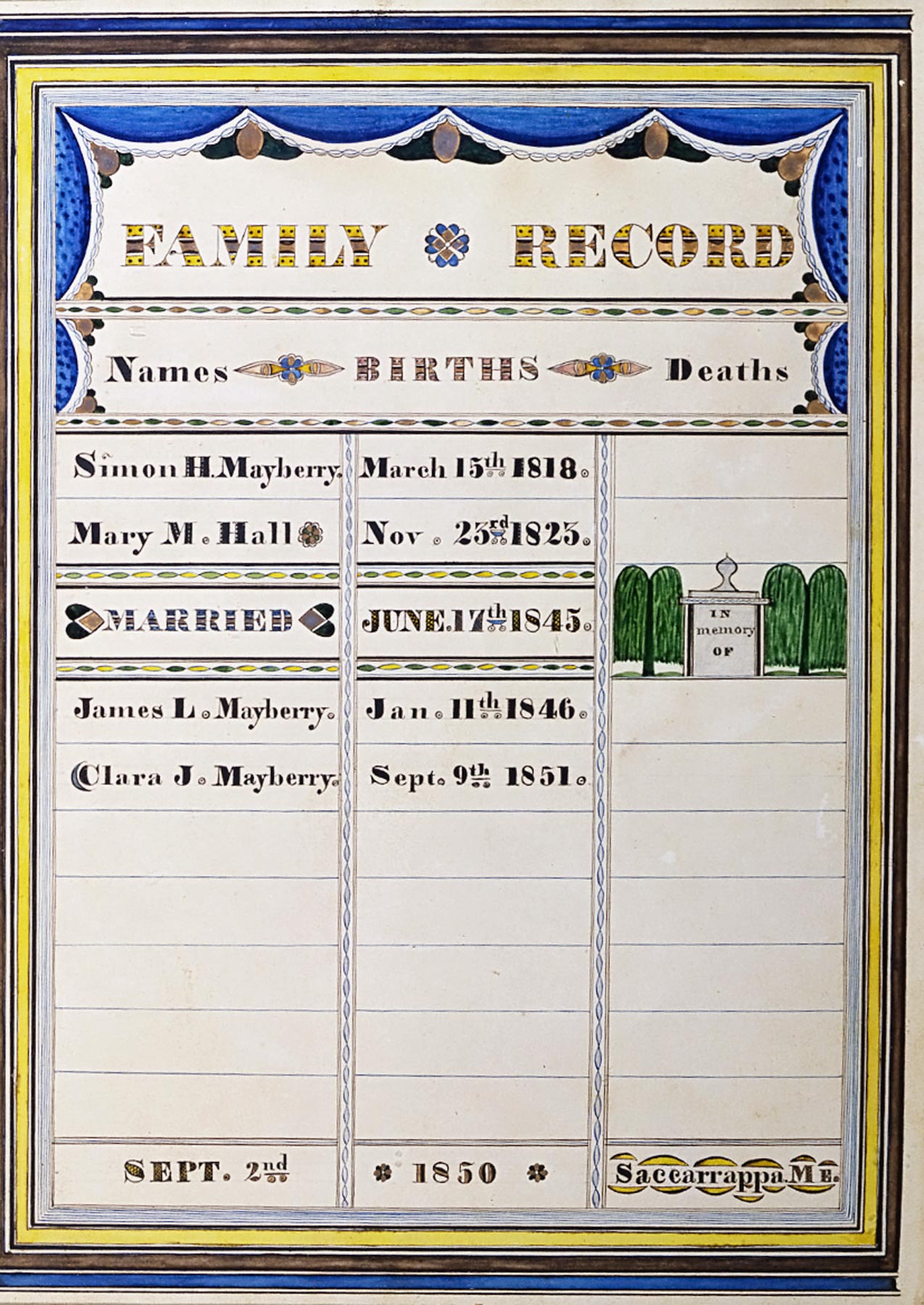

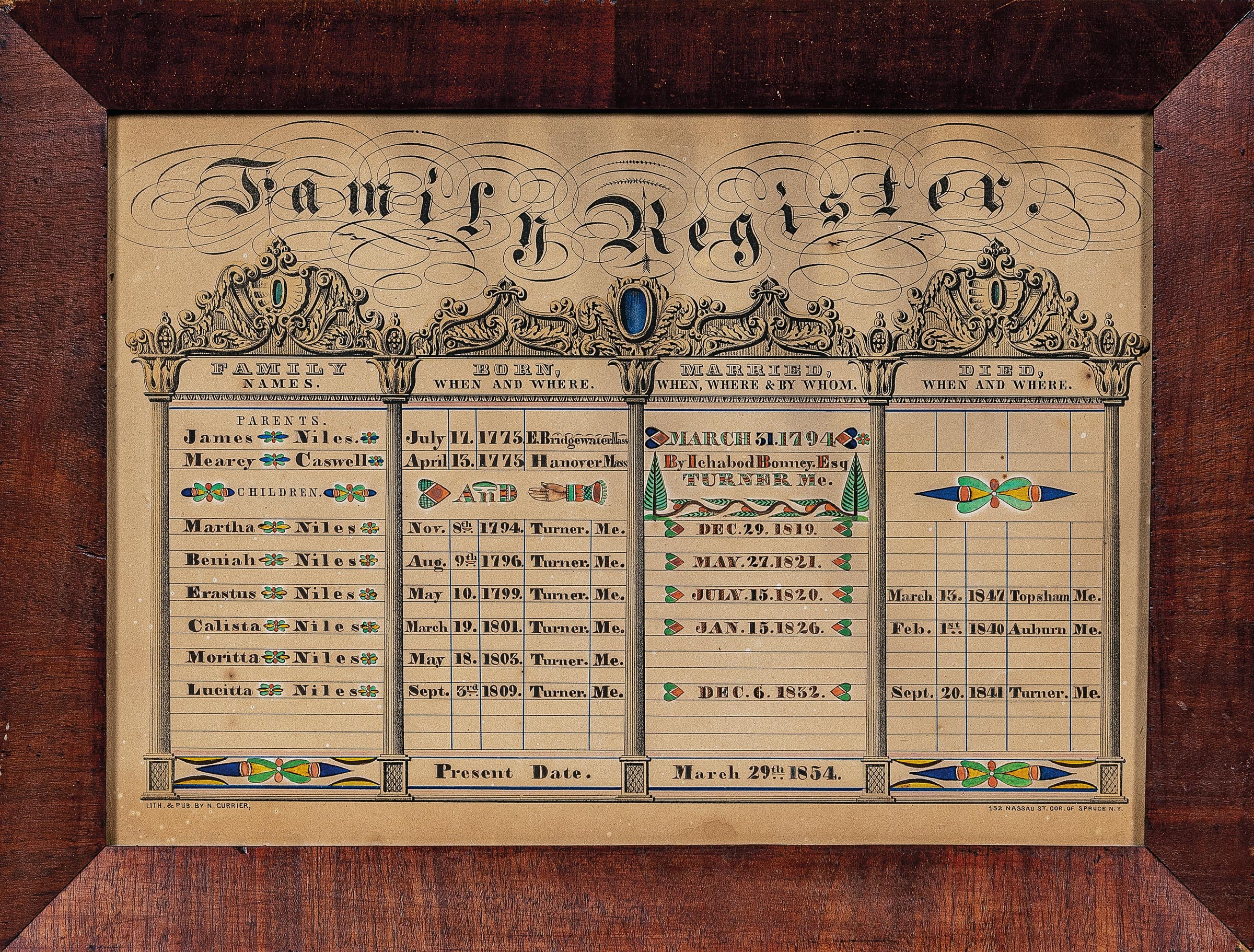

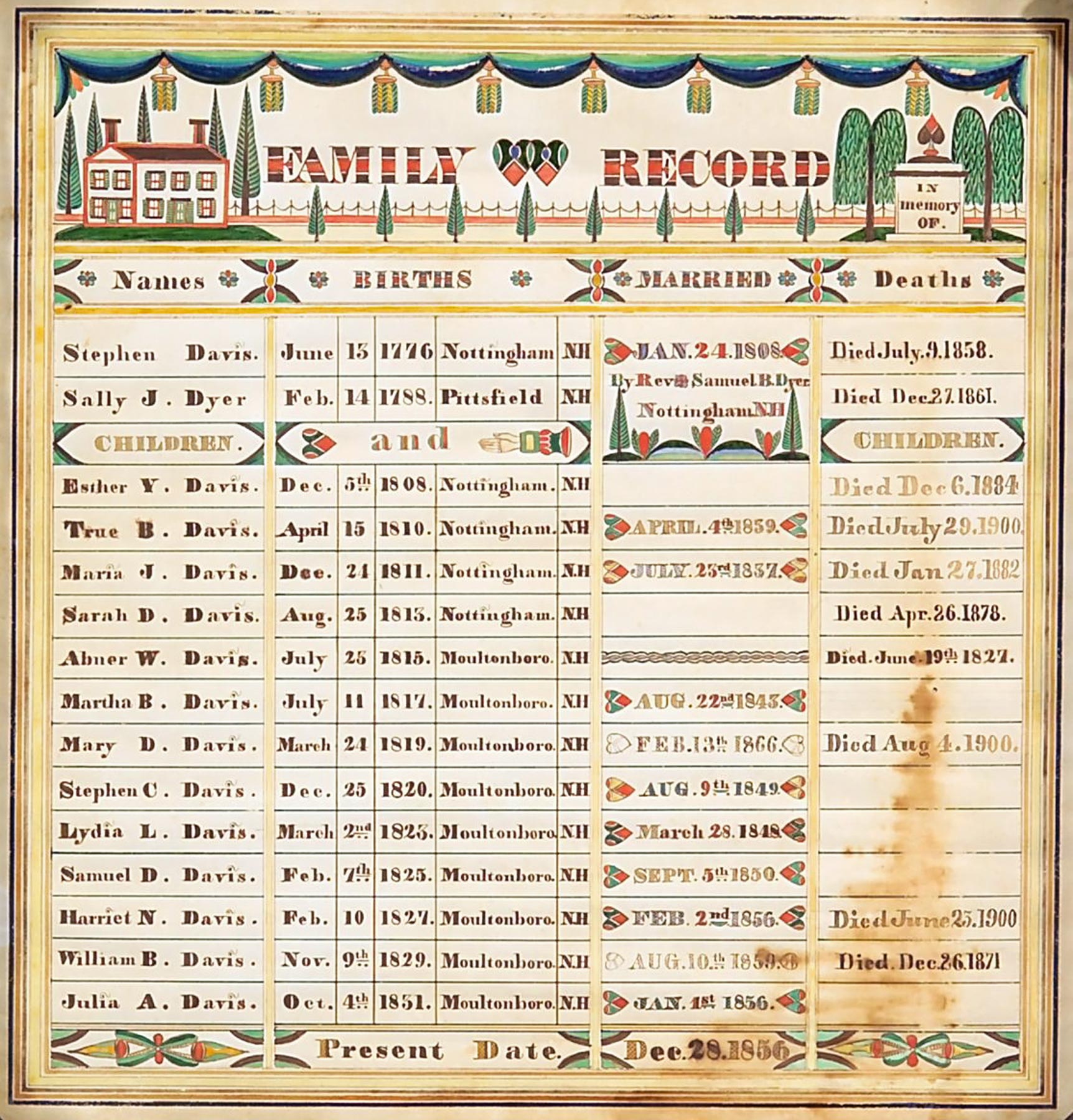

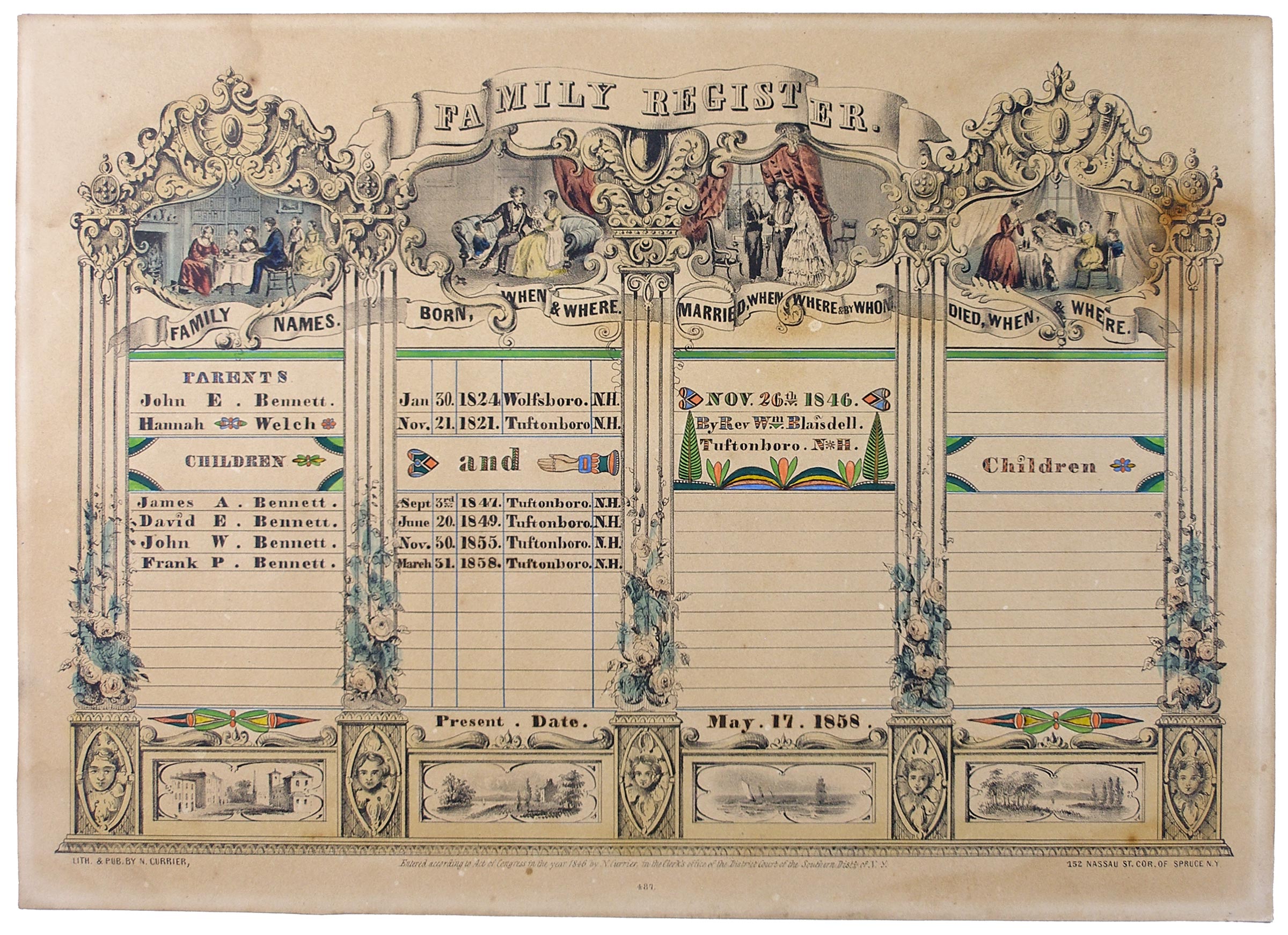

A new genre of American artwork, the “family record” or register, appeared just prior to the Revolutionary War. These illuminated manuscripts recorded the births, marriages, and deaths of family members on a single sheet of paper, typically enhanced with images or designs painted in watercolor. The decorative quality of such family records encouraged owners to have them framed and displayed in their homes. For families that could not afford, or did not want, painted portraits of themselves or their children, family records offered an alternative that recorded milestones in the lives of family members, if not their appearance. The large number of surviving family records make clear that many families had sufficient income to purchase these relatively inexpensive hand-painted artworks and provide additional evidence of the importance of original art in early American homes. The popularity of family records also led to the production of watercolor and needlework examples as part of the education offered to young women at many female academies.

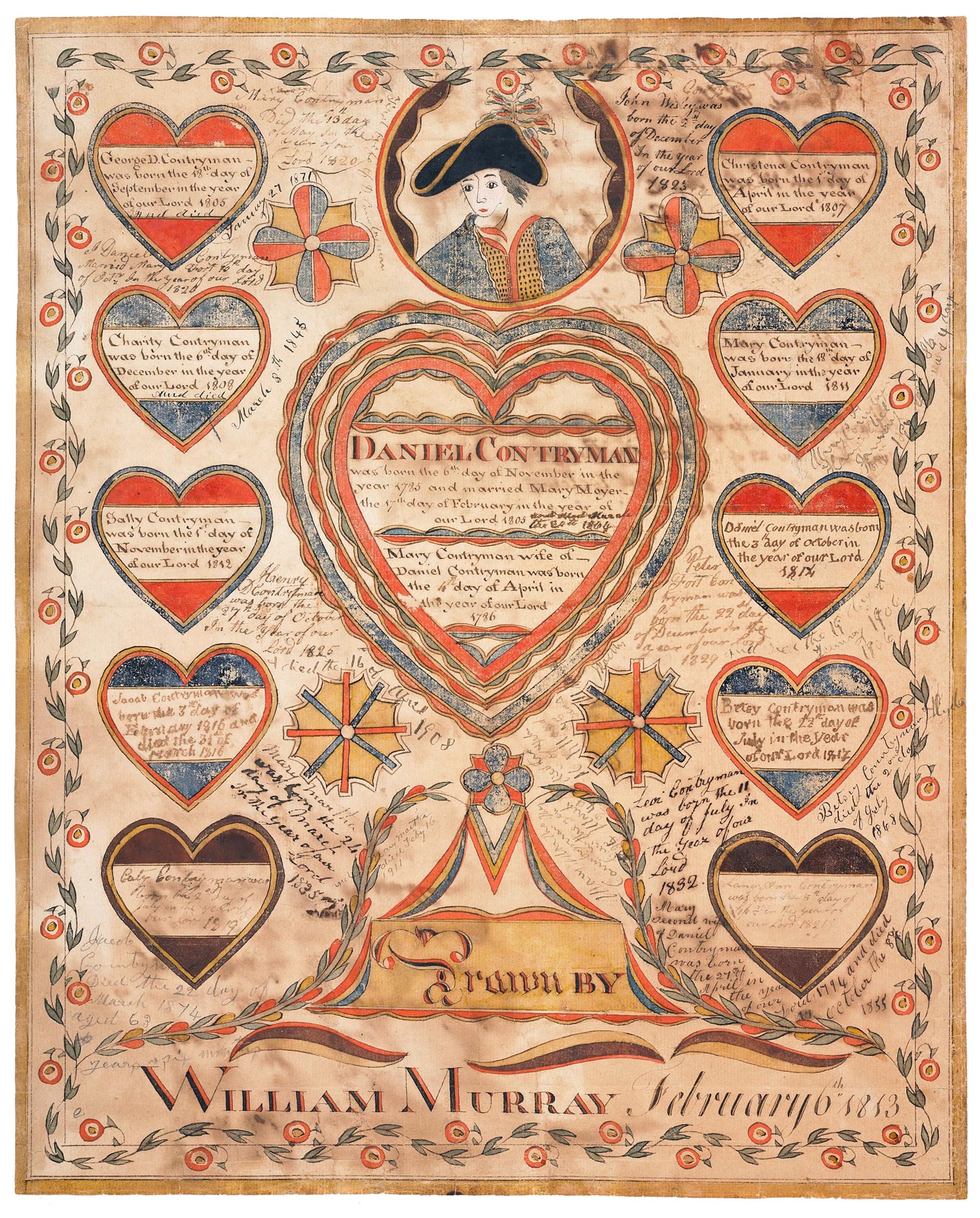

In addition to offering evidence of the importance of family ancestry in early America, the proliferation of family records was also a manifestation of the prevalence of disease and high infant mortality rates. It was not without justification that many parents feared that some of their children would not survive infancy or live to adulthood. Family records provided an opportunity to document all members of a family together at least once, although children who had died before the work was begun are sometimes listed by the artist. While the importance of family and lineage was common throughout early America, these decorative records were primarily a regional art form, with most examples being produced in New England and eastern New York. 1 Combining ornamental script with literal or symbolic watercolor iconography, these artworks were created by several identified artists and more than a few anonymous practitioners. Family records often replaced the practice of adding names in the family Bible, making them the primary genealogical artwork in many Northeastern homes. 2

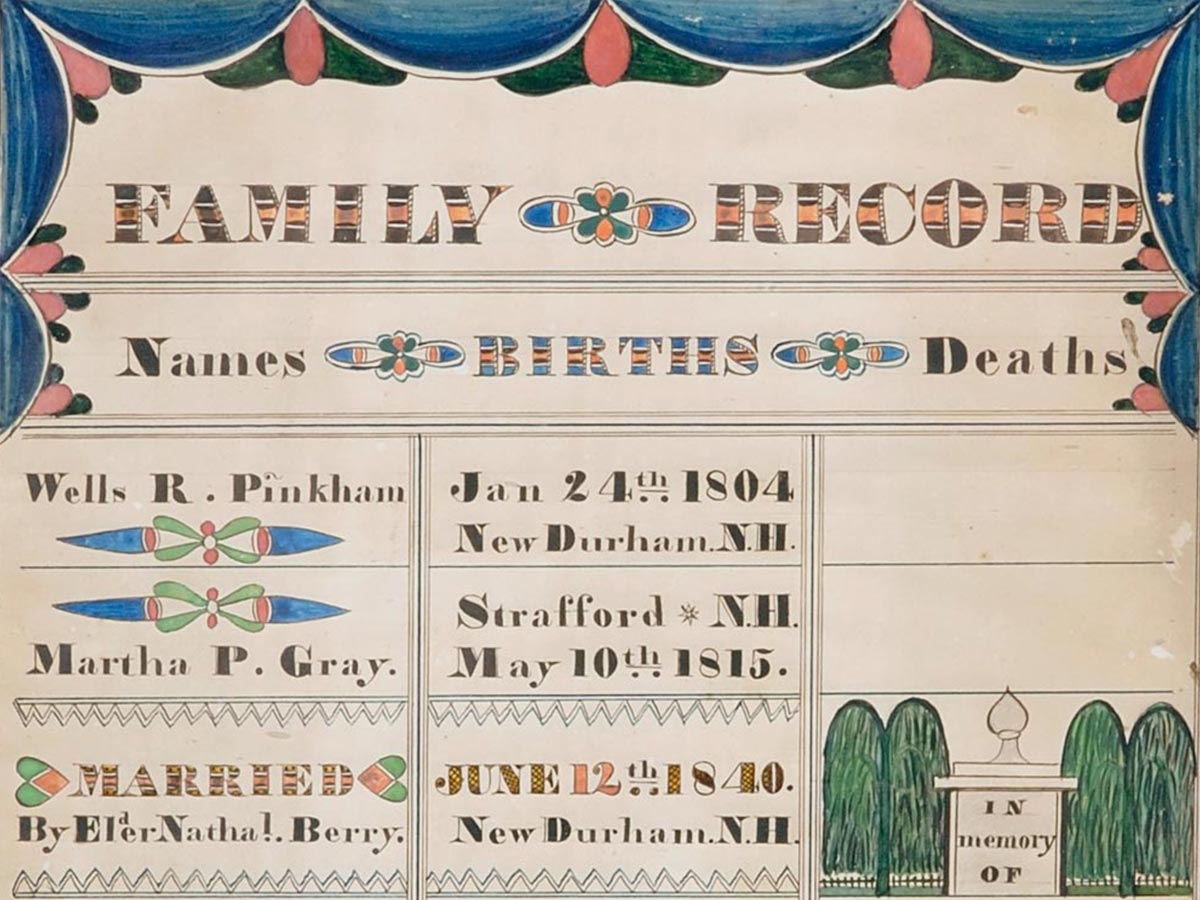

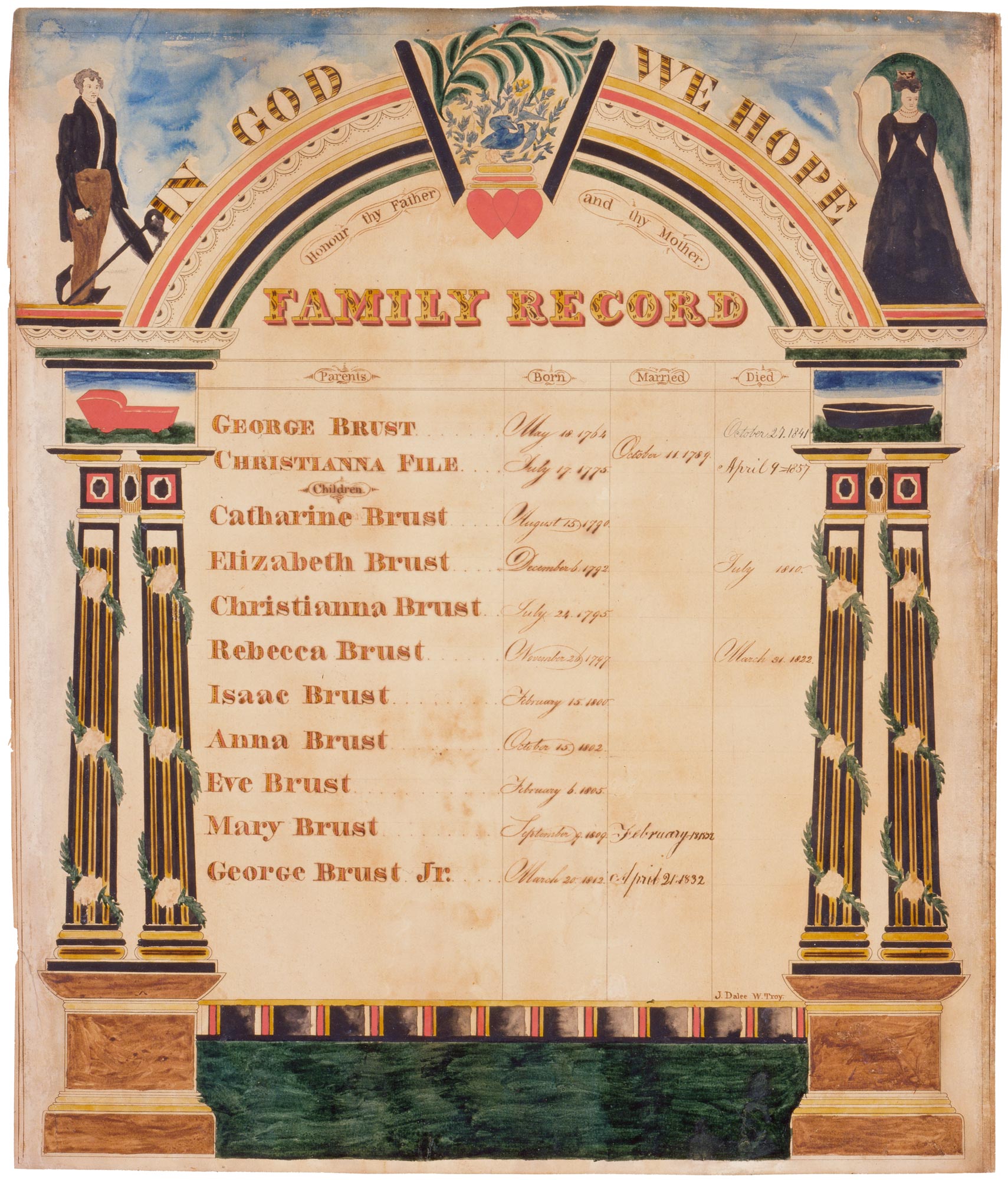

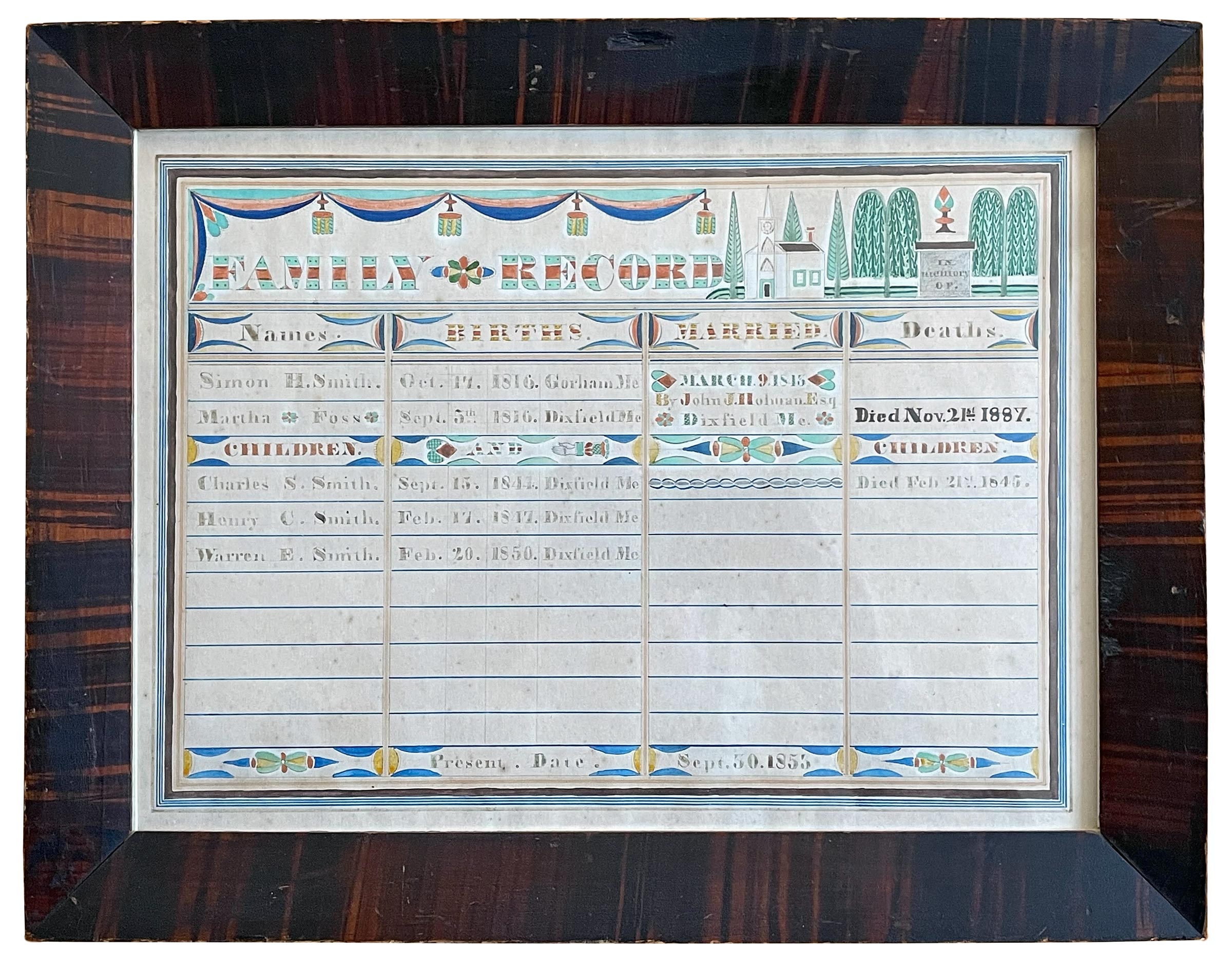

The design for family records became standardized in 1820s. Beneath a title that identifies the document as a family record or register, columns were arranged in which names, births, marriages, and deaths were inscribed. This format was used by Justus Da Lee (1793–1878), who was also a prolific painter of miniature portraits. (Fig. 1) Dividing the sheet into four columns, Da Lee combined symbolic and explicit images above the inscriptions to draw attention to the information provided below. The family record Da Lee painted for the family of George and Christianna Brust of Rensselaer County, New York, replicates the design Da Lee used consistently. A pair of conjoined red hearts at the top acknowledges the couple. To either side, Da Lee painted a man with an anchor, a symbol of hope and birth, above a cradle, and a woman dressed in mourning attire beneath a willow tree above a coffin.

The Heart and Hand Artist

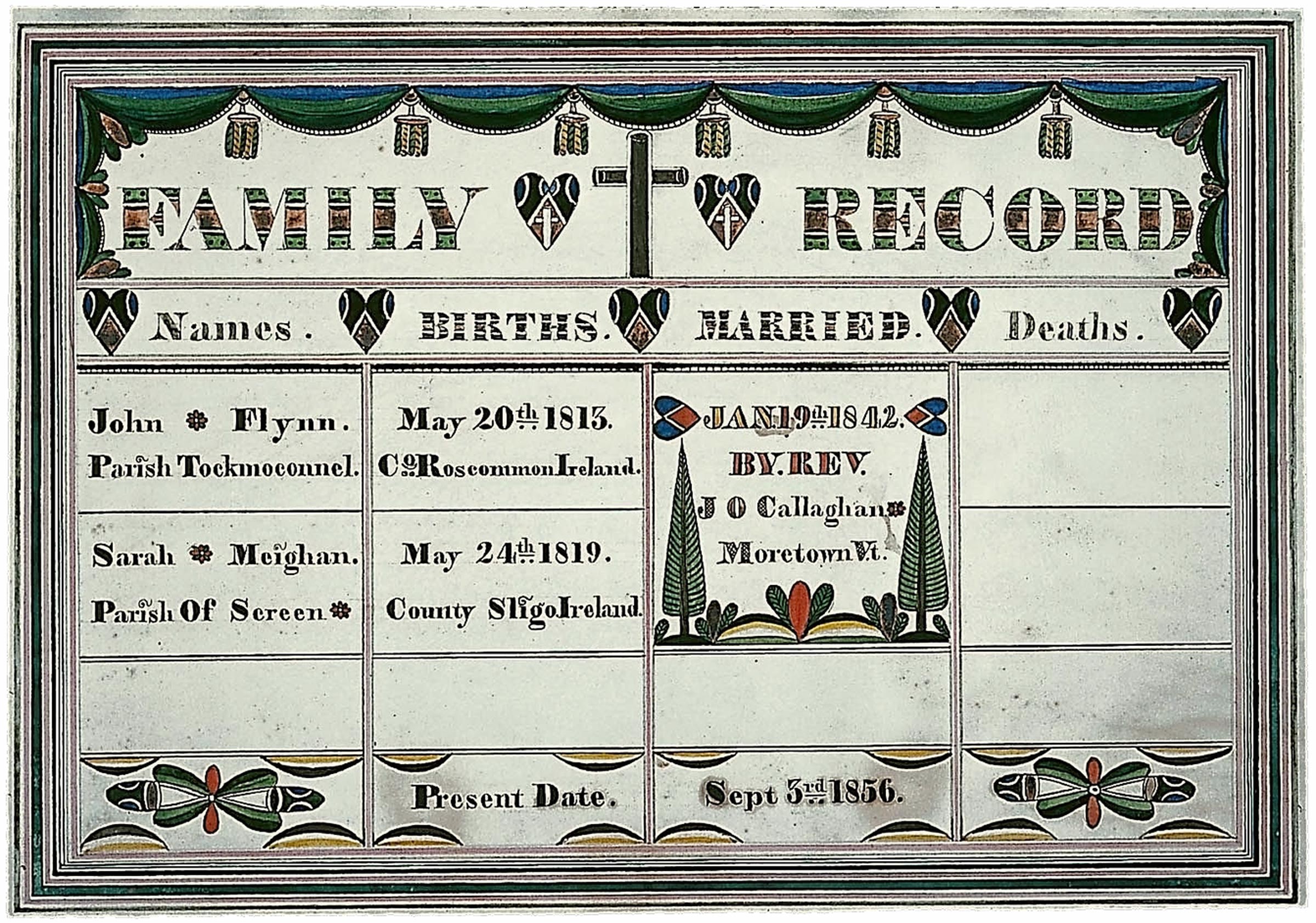

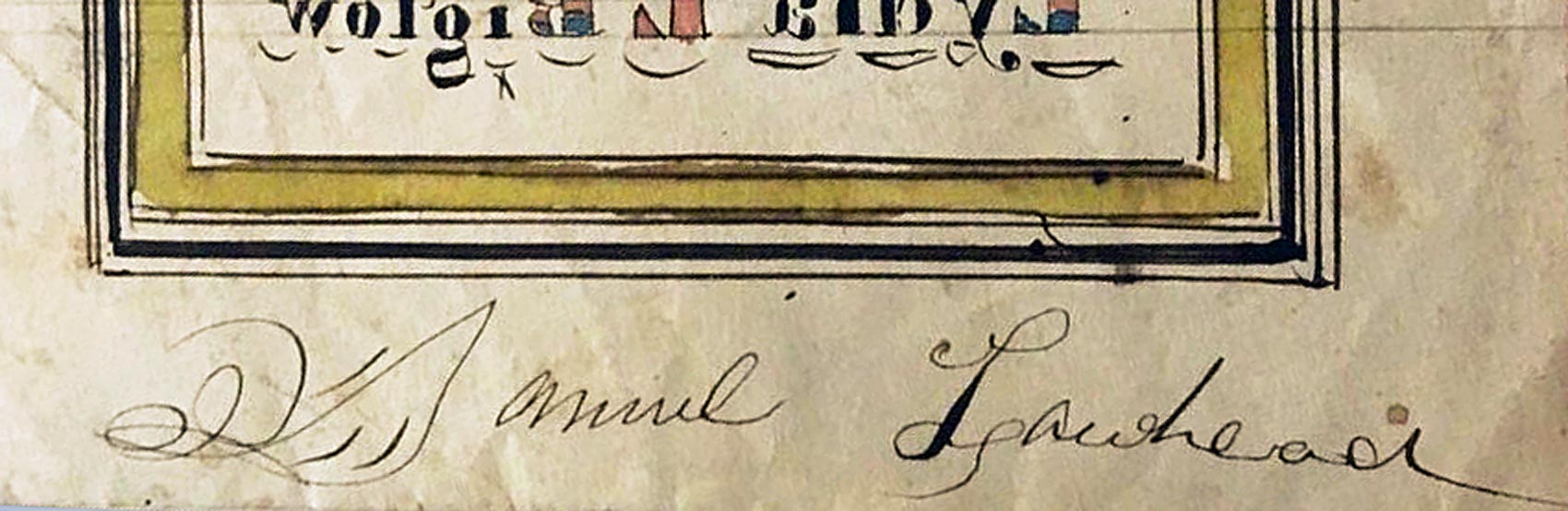

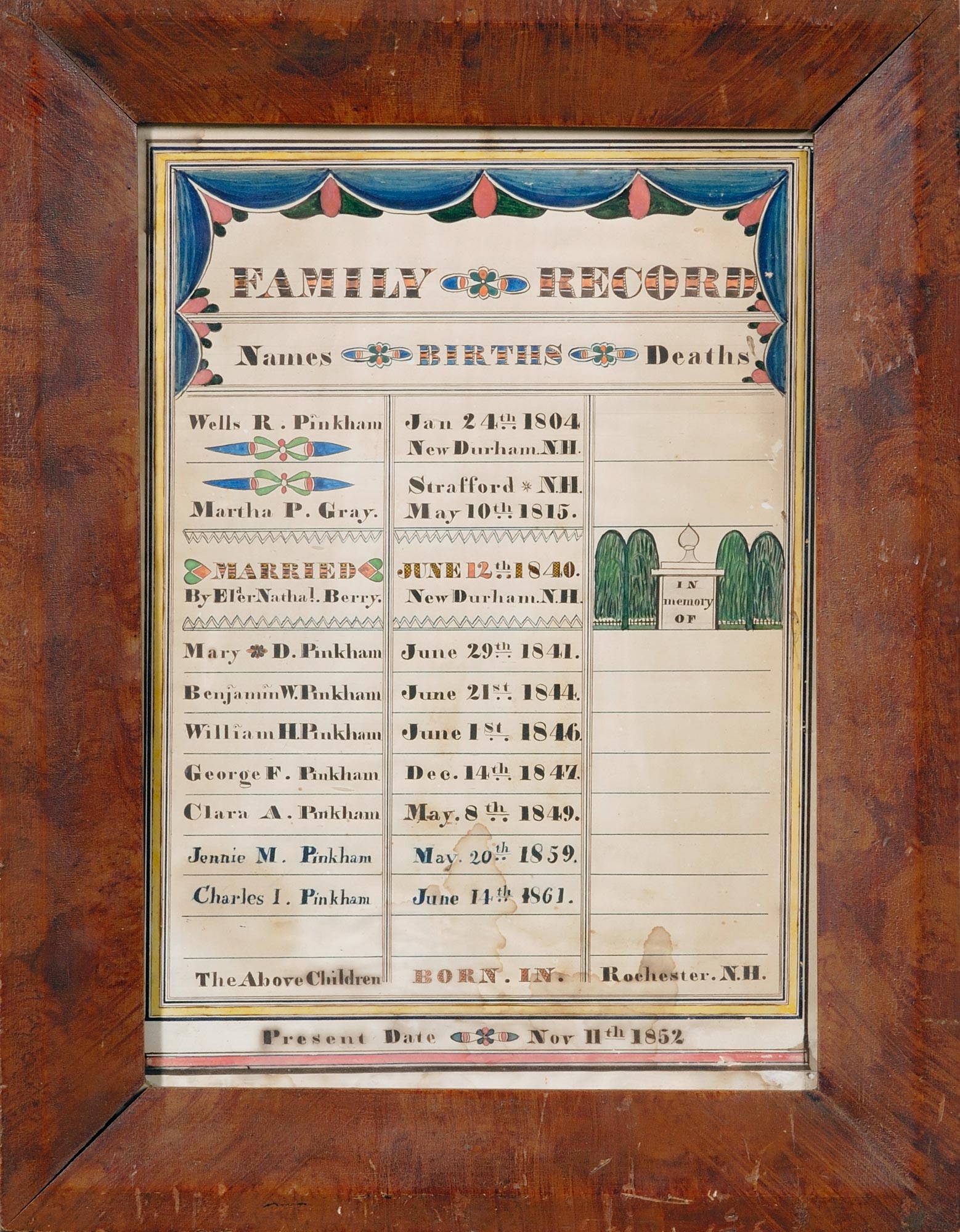

From the late 1840s to the late 1850s, a singularly inventive artist known only by the appellation “The Heart and Hand Artist” produced a variety of ink and watercolor family records, as well as birth and marriage records, and tokens of affection or friendship. This painter was active primarily in New Hampshire, while a smaller group of works were produced for Maine residents, along with six in Vermont, and three in Pennsylvania.7 The records were painted on both vertical and horizontal sheets of paper, and faint layout lines that helped the artist keep letters of consistent size are evident on several family records and on most of the birth records and tokens of affection. No other painter of family records is known to have produced a more imaginative array of records or traveled as widely. The body of work shows great consistency, and the artist’s formats and motifs evolved, becoming more ambitious and decorative over time.

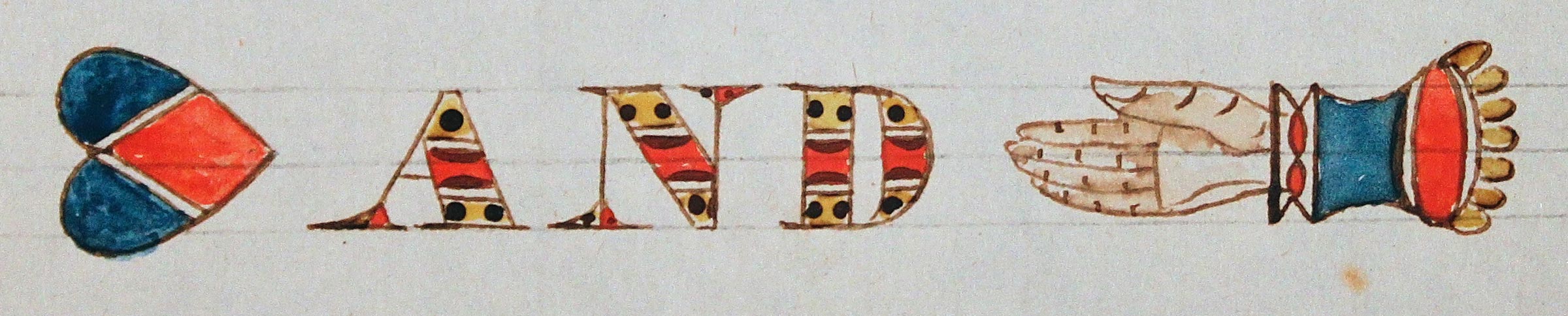

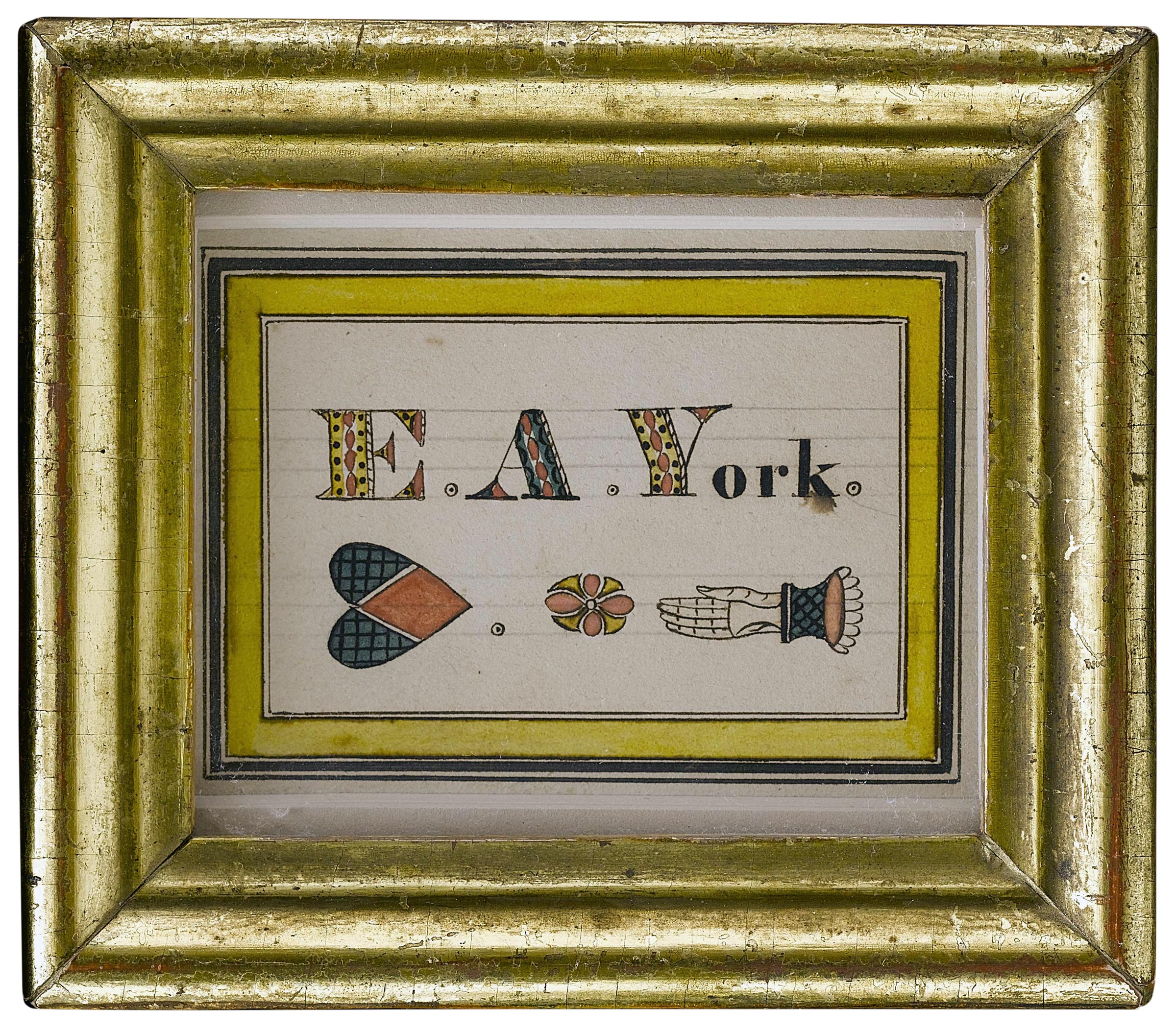

The name “Heart and Hand Artist” derives from the painter's frequent addition of a heart turned sideways and an open right hand pointing left, separated by the word “and” to form a rebus. (Fig. 6) The artist’s choice of this image as a signature motif played on ancient and contemporary references to the symbolic meaning of hearts and hands. The anatomically inaccurate two-lobed heart had been used to represent the love of God since the Middle Ages. By the time this artist employed it, the heart had also come to symbolize romantic and familial love, as well as humanity and brotherly love. Hearts had been used as decorative motifs on a variety of household items made in early America, from furniture to wrought iron tools and implements, and Mother Ann Lee (1736–1784), founder of the United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing, commonly known as the Shakers, instructed her followers to “Put your hands to work, and your hearts to God.”8 An open hand with a heart in its palm was part of the iconography of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows, representing charity given with an open heart.9 (Fig. 7) The motif used by the Heart and Hand Artist reflected the common understanding of heart and hand symbolism at the middle of the nineteenth century, and it was particularly appropriate on documents that expressed the bonds of familial love.

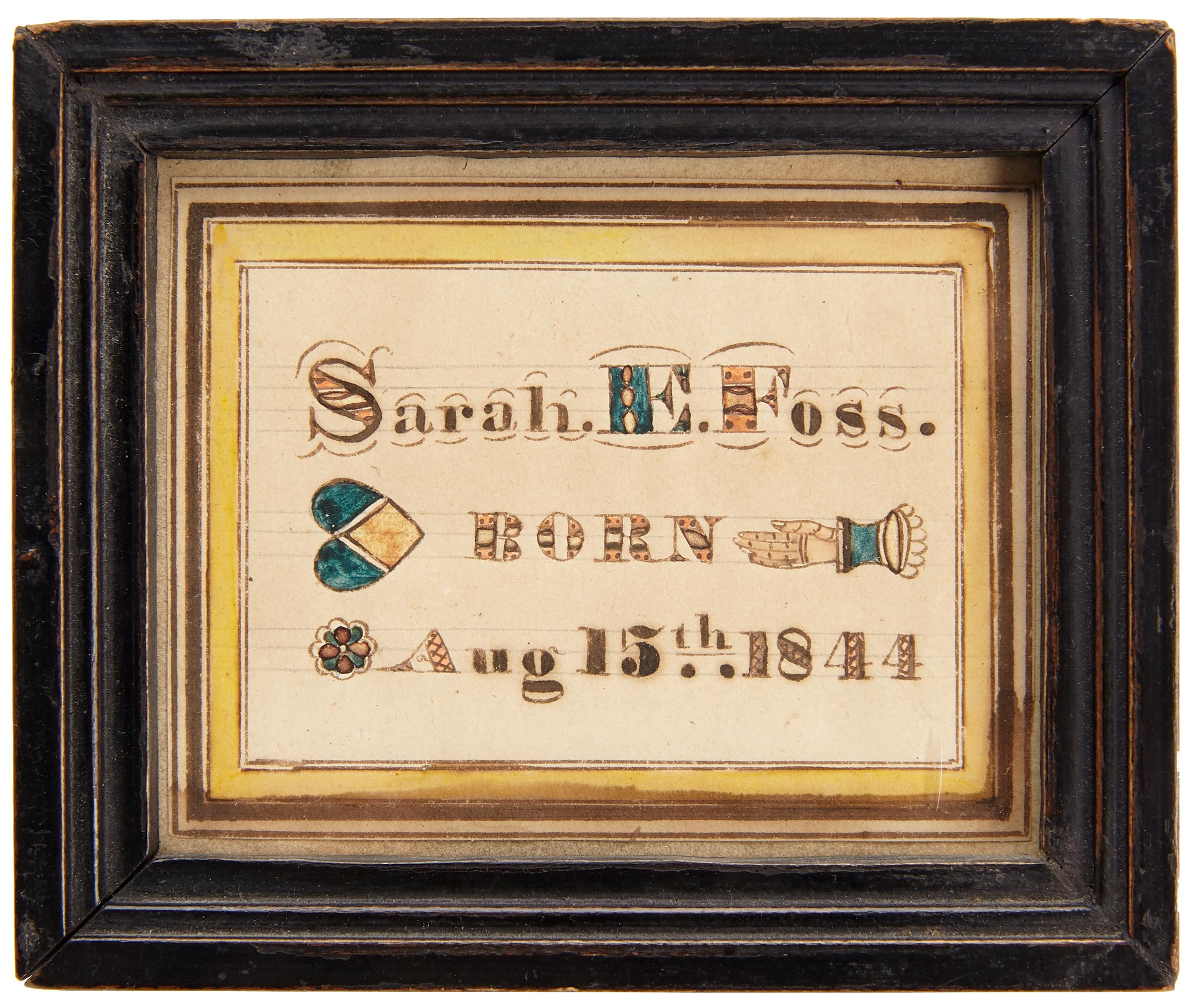

A birth record includes the name of an individual and their birth date, sometimes adding their birthplace. Related works, generally called tokens of affection, include only a name, and ink or watercolor designs. These modest keepsakes were produced in New England, although less frequently than in Pennsylvania’s German-American communities.12 No other artist working in New England is known to have created as many of these small pieces as the Heart and Hand Artist. Most were likely produced in the early to middle 1850s, despite several being dated well before the artist’s known period of activity. After 1850, printed records had probably begun to diminish the artist's ability to find work. Recognizing that painting family records alone could no longer sustain a livelihood, the artist may have begun to offer birth and marriage records and related works to bridge the gap.

Perhaps in 1851, the Heart and Hand artist painted a birth and marriage record for Eli S. Harnish (1829–1879) and Elizabeth Eshleman (1831–1860) who were married that year and lived in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania.13 (Fig. 17) What brought them to Pennsylvania after having worked in northern New England for more than a decade is unclear. Perhaps the artist was from Pennsylvania, and, like James Osborn, had moved to New England, but maintained ties to the State. The production of marriage and birth records was well established in Pennsylvania, which may explain where the idea to produce similar artworks in northern New England originated. Neither conjecture, however, can be verified without knowing the artist’s name.

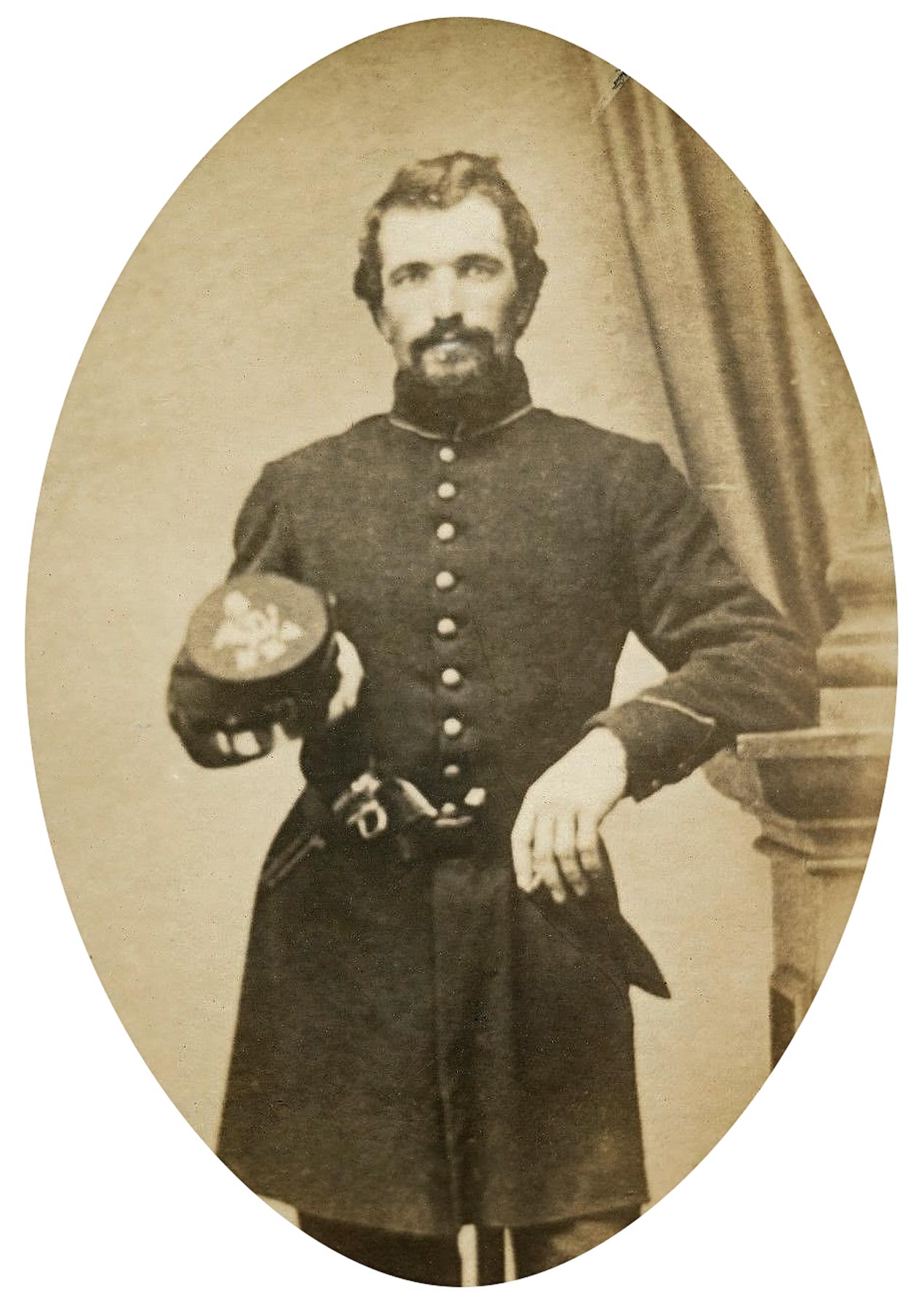

Two children were born to the Harnishes: David in 1853, and Sarah Ann in 1858. Elizabeth Harnish died prematurely in 1860, and the following year, with the start of the Civil War, Eli enlisted in the 12th Pennsylvania Reserve Regiment (41st Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry). Wounded at the Battle of South Mountain in Maryland on September 14, 1862, he received a medical discharge in 1863. The next year Eli enlisted in the 79th Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers. Eli was wounded at the Battle of Bentonville, North Carolina, and after recovering, he was mustered out in 1865.15 In 1866 Eli and Catherine B. Rhinier (1846–1903) were married, and he was working at a Lancaster County stone quarry in 1870. Of the couple's five children, the last, a son, was born seven months after Eli died. Eli Harnish retained the birth and marriage record that documented Elizabeth, his former wife, and the mother of his first two children, throughout his second marriage. He possibly considered this modest record of the start of their short life together to be of indispensable significance.

Between 1850 and 1856, the artist produced a host of birth records and tokens of affection, with none measuring more that 3 ½ x 4 ½ inches. Most were probably made as mementos for children and youths, although some may have also been intended for adults. The birth record of Sarah E. Foss (1844–1935), who was born in Dover, New Hampshire, is typical of these small art works. (Fig. 19) Sarah's birth record includes a variant of the rebus, with “BORN” substituted for “AND.” Most of these little artworks were likely inserted in a Bible or an album, which helped preserve their vivid colors.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Jane Katcher, Robert Shaw, and David Schorsch for their support of this project.

About the Author

1 The German-American Fraktur tradition mostly documented milestones in the lives of individuals, including births, baptisms, and marriages. Family registers (Familien Register) documenting all members of an immediate family together on a single sheet were also produced in German-American communities although in much smaller numbers. Corinne and Russell Earnest, To the Latest Posterity: Pennsylvania-German Family Registers in the Fraktur Tradition (University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press for The Pennsylvania German Society, 2004), 26.

2 Peter Benes, “Family Representations and Remembrances: Decorated New England Family Registers, 1770-1850” in D. Brenton Simons and Peter Benes, eds., The Art of Family: Genealogical Artifacts in New England (Boston, MA: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2002), 14.

3 The most thorough discussion of the work of Murray and his followers is Arthur B. and Sybil B. Kern, “Painters of Record: William Murray and his School” in The Clarion 12, no. 1 (Winter 1986/1987): 28-35, issuu.com.

4 In addition to painting family records and mourning picture, Osborn also decorated a room in the Richard King House in Scarborough, Maine, a writer noted on a visit: “One wall from the dado to the ceiling, was devoted to a painting called ‘Solomon’s Temple;’ another side of the room displayed what was called ‘The Enterprise and Boxer;’ another showed an ‘Equestrian View of Gen. Washington;’ and over the mantel was emblazoned the ‘Arms of the United States,’ occupying the whole wall. I think the artist’s name was Osborn.” J. W. T., “The Mansion and Tomb of Richard King” in Maine Historical and Genealogical Recorder, Vol. II (Portland, ME: S. M. Watson, 1885), 127. The most thorough study of Osborn and his work is Arthur and Sybil Kern, “James Osborn(e), Maine Folk Painter” in Folk Art (Summer 1994): 42-51, issuu.com.

5 Osborn may have scouted Portland before he moved there. A contradictory family record inscribed “Drawn by James Osborn Portland 1827” is in a private collection.

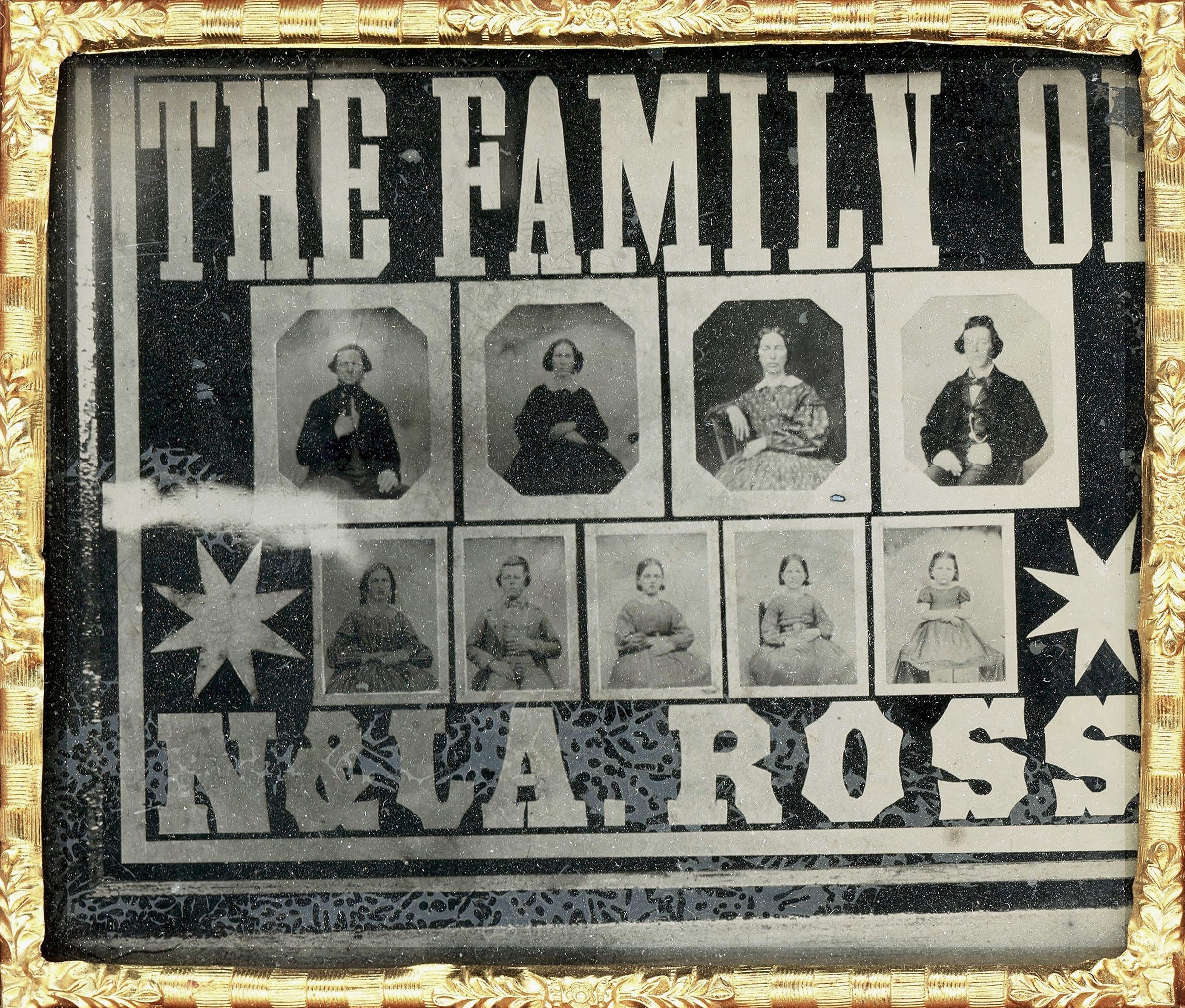

6 Family records that include portraits appear most often in Maine than elsewhere. Besides Osborn, the unidentified painter of the 1818 family record of the Ingersoll family of Columbia, Maine, included nine half-length family portraits. D. Brenton Simons, “Families and Portraiture” in Simons and Benes, eds. The Art of Family, p. 94, fig. 5.

7 Pennsylvania works attributed to the Heart and Hand Artist are discussed in Jane Katcher, David A. Schorsch, and Ruth Wolfe, eds., Expressions of Innocence and Eloquence: Selections from the Jane Katcher Collection of Americana (Seattle: Marquand Books, in association with Yale University Press, New Haven, CT, 2006), p. 334, fig. 35.

8 Cynthia Schaffner and Susan Klein, Folk Hearts: A Celebration of the Heart Motif in American Folk Art (New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1984), pp. 9-10, figs. 6 and 7; Edward R. Horgan, The Shaker Holy Land: A Community Portrait (Harvard, MA: Harvard Common Press, 1982), 89. The refined design and fine craftsmanship of Shaker architecture, furniture, and domestic accessories may be credited, in part, to the adherence of Shaker craftspeople to Mother Ann Lee's admonition.

9 An 1843 article described an Odd Fellow in Boston who needed aid. He drew “the secret designation of membership in the order” on a piece of paper, which was recognized by another member who “extend[ed] to me, ragged and wretched as I was, the fellowship of his heart and hand.” J. W. Ingraham, “Extracts from the 'Odd Fellow,'” The Symbol, and Odd Fellows Magazine 1, no. 4 (Boston: Bro. T. Prince, 1843), 83.

10 Georgia Brady Barnhill, “‘Keep Sacred the Memory of Your Ancestors’: Family Registers and Memorial Prints” in Simons and Benes, eds., The Art of Family, 60, 63-64.

11 Mrs. Niles’s first name was spelled “Mearcy” on the family record and her tombstone, and “Mercy” on 1860 census, which had no reason not to simplify it. The same year, the artist completed an engraved record for the Daniel Plumer – Elizabeth Card family of Milton, New Hampshire. Bourgeault-Horan Antiquarians, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, Annual Summer Americana Auction, August 6, 2012, lot 47.

12 A New England example is the 1830–1835 birth record made by an unidentified artist for Mary E. Wheelock (1830–1918) of Massachusetts in Beatrix T. Rumford, ed., American Folk Paintings: Paintings and Drawings Other than Portraits from the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, in association with the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1988), p. 346, fig. 295. This artist most likely produced other examples, but none are known.

13 This is one of three Pennsylvania works attributed to the artist. Katcher, Schorsch, and Wolfe, eds, eds., Expressions of Innocence and Eloquence: Selections from the Jane Katcher Collection of Americana, p. 334, fig. 45.

14 The Lancaster Intelligencer, April 6, 1870: 3.

15 “Eli Harnish.” Find a Grave. Accessed August 2, 2021, findagrave.com.

16 It has been suggested that this token of affection was made for the E. A. York, who was born about 1807 in Fairfield, Maine. Katcher, Schorsch, and Wolfe, eds., Expressions of Innocence and Eloquence, p. 334, fig. 45.

17 Rev. J. O’Callaghan, Usury, or Interest, Proved to be Repugnant to the Divine and Ecclesiastical Laws, and Destructive to Civil Society. New York, NY: Self-published, 1824.

18 Isaac (b. 1784) and Lydia (b. ca. 1800) Bigelow were living in Wilmington, Windham County, Vermont in 1850. “United States Census, 1850.” FamilySearch. Accessed December 23, 20210, familysearch.org. Two other works include the ca. 1850 Hodgdon – Varney Family Record in a private collection, and a “card” formerly in the collection of Nina Fletcher Little. The Hodgdon – Varney Family Record is in Schaffner and Klein, Folk Hearts, p. 55, fig. 64, and the card from the Little collection is referenced in Gerard C. Wertkin, ed., Encyclopedia of American Folk Art (New York, NY: Routledge, 2004), 251.

19 Two men named Samuel Lawhead who lived in the United States and whose birth dates make them possible candidates for being the artist are known. One was born in Fayette County, Pennsylvania, in 1822, his family moved to DeKalb County, Indiana, in 1839, and he farmed there until his death in 1907. This man's location and occupation preclude him from consideration. The other Samuel Lawhead, “an Irishman 52 years of age,” attempted suicide in 1859 while he was jailed in Hartford, Connecticut, for drunkenness. The possibility that “an Irishman” named Samuel Lawhead, born about 1807, was associated with the Irish-American community, and it was this man who produced the Flynn-Meighan family record in Vermont is intriguing. His arrest one year after the last dated work by the Heart and Hand artist may be significant. However, without information documenting that this man was an artist, he is identification as the Heart and Hand artist cannot be substantiated.

20 Peter Benes, “Family representations and Remembrances” in Simons and Benes, eds., The Art of Family, 22.