Fancy Dressing Tables

Richard Miller

As I stood before the looking-glass, laying my watch and exhausted purse on the dressing-table and leisurely untying my cravat, I could not forbear a glance of approbation at what I thought a very handsome and very impudent face…

Used for grooming and dressing by both men and women, dressing tables, made of walnut or imported mahogany, with cases and drawers supported by turned or cabriole legs, first appeared in major American urban centers by the 1720s. The form found a strong market among people of means but had mostly fallen out of fashion by the 1780s. After 1800, the form was revived, and dressing tables featuring new designs and ornamental painted surfaces came into vogue. The market for these was particularly strong in New England, where cabinetmakers and ornamental painters exercised enormous freedom in their interpretations of the form and decoration. The large number of surviving post-1800 New England painted dressing tables probably accounts for only a small fraction of the total number that were made.

In the seventeenth century, elite women groomed themselves while sitting at a table before a portable dressing glass. A Dutch genre painting from 1650–1660 depicts a young lady in her chamber who has just risen from bed, the door to the commode ajar (Fig. 1). Wearing a costly lace-trimmed yellow dressing gown and slippers, she sits before a dressing glass on a covered table. A pearl necklace, rings, and silver vessels displayed prominently on the table offer evidence of her wealth and status, and a domestic has set aside her sweeping to affix a length of blue ribbon in her mistress’s hair. A drape is pulled back, revealing the lady looking squarely at the viewer who has intruded upon this private scene. Documenting the clothing and furnishings that were part of her daily grooming ritual, the painting offers a privileged glimpse of one woman as she readies herself to present her public persona.

Eighteenth-century American dressing tables were modeled after the bases of high chests, and cabinetmakers in Boston and Philadelphia often made them en suite with high chests for wealthy patrons. The preferred surface ornamentation on such dressing tables was carving and the grain of the hardwoods from which they were constructed. However, some late baroque, or Queen Anne, Boston examples, along with chairs and other forms produced before 1750, have “japanned” surfaces, a decorative style and technique inspired by Chinese and Japanese lacquerware boxes. Vignettes of animals, landscapes, figures, and other motifs modeled in low relief in gesso were affixed to the surface of furniture painted with a faux tortoiseshell or lacquer ground, resulting in stunning decorative effects (Fig. 2). Japanned dressing tables and matching high chests were extremely costly and, therefore, affordable by only the wealthiest consumers. An interest in surface ornamentation approaching what japanners had achieved would not appear again until the nineteenth century.

After 1800, a new dressing table design was introduced that enabled users to sit with their legs under the case, a more comfortable position than earlier forms with deep, scrolled skirts allowed. Cabinetmakers turned to card tables, whose height, generous width, and open space below provided a more functional model than tall chest bases. Dressing tables were more than merely functional furniture: they served as a reminder of their users’ social status and marital role, making them appropriate furnishings in the bedchambers of stylish neoclassical houses, decorated with brilliant painted walls and vibrant patterned wallpapers.

A neoclassical example with a semi-elliptic front, made in Salem, Massachusetts, about 1805, shows its debt to contemporary card tables, and the fixed accessory box with drawers for toilet articles added on top would become a standard feature of later examples (Fig. 3). In addition to its design, the dressing table’s visual appeal is conveyed through decorative and symbolic cast brass ornaments. A painted white ground serves as a backdrop for gilded oval sunflowers, a vase of flowers, and lengths of ball-and-reel moldings that were reconfigured into swags on the skirt. The color white was associated with ancient Greek temples and sculpture, both of which were originally polychromed, and it became a common feature of the Grecian taste that came to prominence in the early 1800s. White was also seen as representing civility and purity of spirit, and skin color afforded white people numerous advantages. The use of cosmetics by eighteenth-century elite white women to enhance their natural skin color reinforced their social class and showed they did not labor in the sun.1 The vase of flowers centered on the skirt may have represented fecundity, reinforcing a link between dressing tables and their female users.

Designs for elaborate “Ladies Dressing Tables” in George Hepplewhite’s Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Guide (1794) and Thomas Sheraton’s Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing-Book (1802) show that in England the tables were firmly gendered furniture forms.2 Hepplewhite intended them to be used for storing “combs, powders, essences, pin-cushions, and other necessary equipage,” which mirrored the function of dressing tables in the United States. The association between dressing tables and women is explicitly expressed by a c. 1820 New England example bearing the silhouette likeness of the woman who used it painted on the splashboard (Fig. 4). Sitting at a dressing table and preparing herself for the day ahead or for sleep was a private indulgence that had been enjoyed previously only by women of high status. After about 1820, dressing tables used for grooming had become part of the daily lives of a growing number of middle-class women.

The proliferation of painted dressing tables in New England coincided with the rise of “Fancy.”3 An aesthetic movement and decorative philosophy that viewed everyday objects as offering opportunities for creative expression and bringing color and pattern into the home, Fancy delighted the eye and the imagination. The rise in popularity of paint-decorated furniture, along with ornamented metalwares, ceramics, woven carpets, bedcovers, painted interiors, and wall murals, shows the wide influence Fancy exerted on utilitarian objects and the domestic environment. Fancy furniture had been considered as fashionable as hardwood furniture among affluent consumers in Boston, New York City, Baltimore, and Philadelphia from the mid-1790s through the first decade of the nineteenth century. Afterward, the desire for richly decorated and affordable handmade furniture among an expanding population was satisfied by joiners working outside of urban centers.

Fancy dressing tables were typically constructed with a main case containing a single full-width drawer on turned or tapered legs. Equipped with an accessory box containing small drawers mounted on top, a scrolled backsplash prevented small items from falling off the back of the case. This design became ubiquitous, but their painted decoration gave each singularity. Ornamental painters experimented with an array of colors, techniques, and designs, including freehand painting, stencils, and manipulating wet paint with various materials to produce lively, abstract patterns. The use of paint to dramatically alter the appearance of nearly identical furniture forms is seen in a Fancy dressing table made between 1815 and 1825 in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and a near duplicate made of mahogany in Portsmouth or Salem, Massachusetts (Figs. 5, 6). The pine and maple Fancy dressing table was acquired by Abraham Wendell (1785–1865), a member of Portsmouth’s mercantile elite, for his wife, Susan Gardner Wendell (1786–1849), and the mahogany version was likely owned by an individual of Wendell’s social rank. Both have elliptical fronts, half-elliptical sides, accessory boxes on ball feet that are miniature duplicates of the main case, and similar turned legs capped with ring turnings. The cabinetmakers chose to ornament the drawer fronts on each piece consistently—one with stenciled grapes and leaves, the other with crotch mahogany veneers. The gilt striping on the legs of the Fancy dressing table is an ingenious interpretation of the turn-twist carving on the legs of the other. Contrast and surprise were important elements of Fancy. The deep blue mottled tops of the Fancy dressing table serve as a counterpoint to the light blue case, with putty pressed into the wet paint to create a repeating pattern resembling oyster shells.

White remained a popular color for dressing tables, but yellow came to predominate. The preference for yellow mirrored the brilliant wall colors that became fashionable after 1790, and canary-yellow English transfer-printed earthenware imported to the United States in large quantities after 1800 (Fig. 7). Furniture painted white or yellow was also more visible at night in rooms lit with candles and lamps, enabling the furniture to bring light to the shadowed places they occupied. One vivid yellow example, crafted by Grover Spooner (1798–1858) of Barre, Massachusetts, in 1835, was purchased by thirty-two-year-old Martha P. Robinson for three dollars prior to her marriage (Fig. 8).4 Dressing tables cost relatively little to construct, and parts could be mass produced, making them profitable for cabinetmakers.

Spooner’s dressing table is rare because we know who made it, where it was made, and who bought it; the vast majority of other makers, origins, and owners are unknown. Fortunately, from the signatures on several pieces, we do know the identities of a few craftsmen who built and/or decorated a group of closely related Fancy dressing tables, the most noteworthy examples produced in New Hampshire. They were likely made between 1828 and 1835 by craftsmen working a hundred miles northwest of the seacoast city of Portsmouth, in the Sullivan County towns of Newport and Croydon. Ten examples comprise this, the largest known group of affiliated Fancy dressing tables made in the United States. Three are signed by their makers and/or decorators—Martin Bullock (1810–1876), David Colby (active c. 1835), and David Harris (1803–1855). This group of tables allows an examination of the taste for Fancy furniture among customers living some distance from New Hampshire urban centers, the evolution of the design of dressing tables in Sullivan County, and the network connecting the craftsmen who made them.

Chartered by Governor Benning Wentworth (1696–1770) in 1761, Newport was settled in the summer and fall of 1765 by six men from Killingworth, Connecticut, who cleared land, brought in a crop of rye, and returned the following June with more settlers. Newport’s location on the Sugar River provided water power for a grist mill established before 1787, and the town’s first cotton mill opened in 1813. The Croydon Turnpike, linking Newport, Croydon, and Lebanon, was built in 1806, easing travel between these communities.5 Newport grew to become a prosperous agricultural, manufacturing, and commercial center, with many fashionable residences and commercial buildings (Fig. 9). With the forming of Sullivan County in 1827, from what had been part of Cheshire County, Newport became the county seat and a courthouse was built there.

With its growing population and wealth, Newport attracted cabinetmakers and chairmakers.6 Cabinetmaker Willard Harris (1782–1848) opened a shop in 1808, William Lowell (1795–1839) began producing furniture in Newport in 1818, and the chairmaking firm of Dame & Howe was established c. 1830. From 1820 until 1837, when the nationwide economic depression sent Newport into decline, cabinetmaking was “one of the most extensive and successful branches of business in town,” according to Edmund Wheeler. Harris and Lowell operated the town’s “two large rival shops,” producing furniture for residents of Newport and the surrounding area. Harris harnessed water power from the Sugar River to operate his woodworking machinery, employing upwards of fifteen workers to produce furniture.7

The common link shared by Martin Bullock, David Colby, and David Harris appears to have been Harris’s father, Willard Harris. This explains how related Fancy dressing tables came to be made by different men working in and near Newport over a period of about seven years. Harris placed an advertisement in the New-Hampshire Spectator on February 18, 1828, offering mahogany secretaries, sideboards, sofas, bureaus, and a variety of chairs, beds, and tables (Fig. 10). Of particular interest are “Fancy and common dining CHAIRS handsomely painted” and “Dressing Tables & Wash Stands.” Whether Harris was the principal maker of Fancy furniture in Newport is not known, but Fancy furniture may have constituted a sizable portion of his shop’s output. The furniture required skilled ornamental painters, and the advertisement ends by informing customers that Harris and his son David also provided “House, Sign, Carriage and ornamental Painting,” evidence that the firm’s Fancy furniture was painted in-house.

Four of the ten dressing tables in the group represent what is perhaps the earliest dressing table design marketed by Harris (Fig. 11).8 Having a nearly full-width rectangular accessory box with two drawers on top, three have swelled turned legs, one has tapered turned legs, and all have rings on the legs picked out in darker paint. The paint scheme is consistent: they all have yellow grounds, and oval reserves outlined with heavy lines and centered on the splashboard and drawer fronts. Stenciled grapes and leaves are placed within the reserves on the splashboards; spaces flanking the reserves have curving infilled faux grain paint; and the edges of the tops of the main cases are ornamented with stenciled bands of leaves. The grapes and leaves recall the vase of flowers on the Salem dressing table made over twenty-five years earlier.

Two drawers on the example illustrated in Figure 11 (Fig. 11) are inscribed, one “D. Harris” and the other “Hannah Morse Croydon NH.” The signature of David Harris, Willard’s son, confirms that he painted it and may also have built it at his father’s Newport shop. David Harris was twenty-five years old when his father placed the 1828 advertisement, by which time he was an accomplished ornamental artist, painting Fancy furniture produced in his father’s shop along with carriages and signs. The paint scheme featuring heavy lining, reserves, and faux graining was likely the Harris shop style, and it appears with variations on the ten dressing tables.

The ownership history of this dressing table offers insights into the customers for Fancy furniture in Sullivan County. Hannah Morse’s (1830–1920) father, Samuel (1784–1865), was an attorney in Croydon, New Hampshire, located seven miles north of Newport. An 1811 graduate of Dartmouth College, Morse arrived in Croydon in 1815 and married Chloe C. Carrol (1803–1900), the daughter of a Croydon physician. The village’s first lawyer, and later a judge, Morse was one of Croydon’s most prominent residents. The Croydon Turnpike facilitated Morse’s purchase of this dressing table from the Harris shop for Chloe’s use, probably shortly after they married, thus dating it to a period between their marriage, in 1827, and Harris’s 1828 advertisement. Located in a bedchamber in the Morse’s fashionable neoclassical house, built in 1815 (Fig. 12), the dressing table’s contemporary design was an expression of the progressive taste and social status of this educated and influential couple. The dressing table’s importance to the Morse family over at least two generations is clear from Hannah’s inscription, verifying her later ownership of her mother’s dressing table.9

By 1830, a new dressing table design had been introduced at the Harris shop, probably by Martin Bullock. Bullock was born on his family’s farm in Grafton, New Hampshire. Twenty years old in 1830, he was working as an apprentice or journeyman cabinetmaker when he built a mahogany classical chest of drawers, a form Harris referred to as a “bureau” in his advertisement (Fig. 13). Bullock proudly inscribed a backboard on the bureau: “Made by Martin Bullock from Gra[f]ton NH Newport August the 18—1830.” The bureau’s projecting top drawer, leaf-carved panels, turn-twist columns, and mahogany veneers show him to be a skilled cabinetmaker working in the current style. This was dressing furniture, with storage drawers on top for toilet items, space for a dressing glass, a scrolled splashboard, and drawers for clothing. It differs from numerous other examples of this popular form in having an impressive semicircular gallery on the top. A more costly alternative to the more common rectangular accessory box on bureaus (such as the one illustrated in Harris’s advertisement), this is the only known hardwood bureau made in New Hampshire to exhibit the feature.10 An earlier analogue of this form is the elliptic gallery on desks made by Porter Blanchard (1788–1871) for the New Hampshire State House in 1819 (Fig. 14). Although Blanchard’s desks had no direct influence on Bullock’s bureau, New Hampshire cabinetmakers knew the geometry of neoclassicism, and the fashion found its way to Newport.

Of recorded dressing tables with galleries, one is signed by Bullock (Fig. 15). Probably made c. 1830, this may be the earliest dressing table with a gallery. The dressing table replicates the top and first full drawer of his bureau, supported on swelled turned legs, and the gallery’s vertical wall was fashioned from a thin board that Bullock bent into a semicircle. Matching the gallery on his bureau, this one is slightly smaller, scaled to fit the dressing table’s reduced dimensions. Except for the stenciled and freehand-painted grapes, leaves, and tendrils on the splashboard, the paint scheme follows the one used on the earlier dressing tables without galleries, including the one signed by David Harris. If Harris painted Bullock’s dressing table, then Bullock most likely worked at Willard Harris’s cabinet shop.

The gallery represents a significant design departure from other New England dressing tables, which soon became more common. Examples with galleries (Figs. 16a, 17, 18), for which Bullock’s can be seen as a precursor, show the continued evolution of the form.11 All were given a yellow ground, tapered turned legs, and stenciled compotes of fruit within dark reserves, replacing the grapes and leaves on the splashboard of Bullock’s dressing table. Instead of reserves painted on the small gallery drawers, which look somewhat cramped on Bullock’s dressing table, circles echo the pressed glass pulls (manufactured in Sandwich, Massachusetts) that replace the stamped brass pulls on Bullock’s. On two examples (Figs. 16a, 17), the curving infill design is painted red-brown, simulating wood grain more effectively and increasing the color contrasts. On Figure 17 (Fig. 17), the overall amount of yellow makes the wall of the gallery and the reserve on the long drawer now appear more prominent, and as they are the same width, the eye is drawn from one to the other.

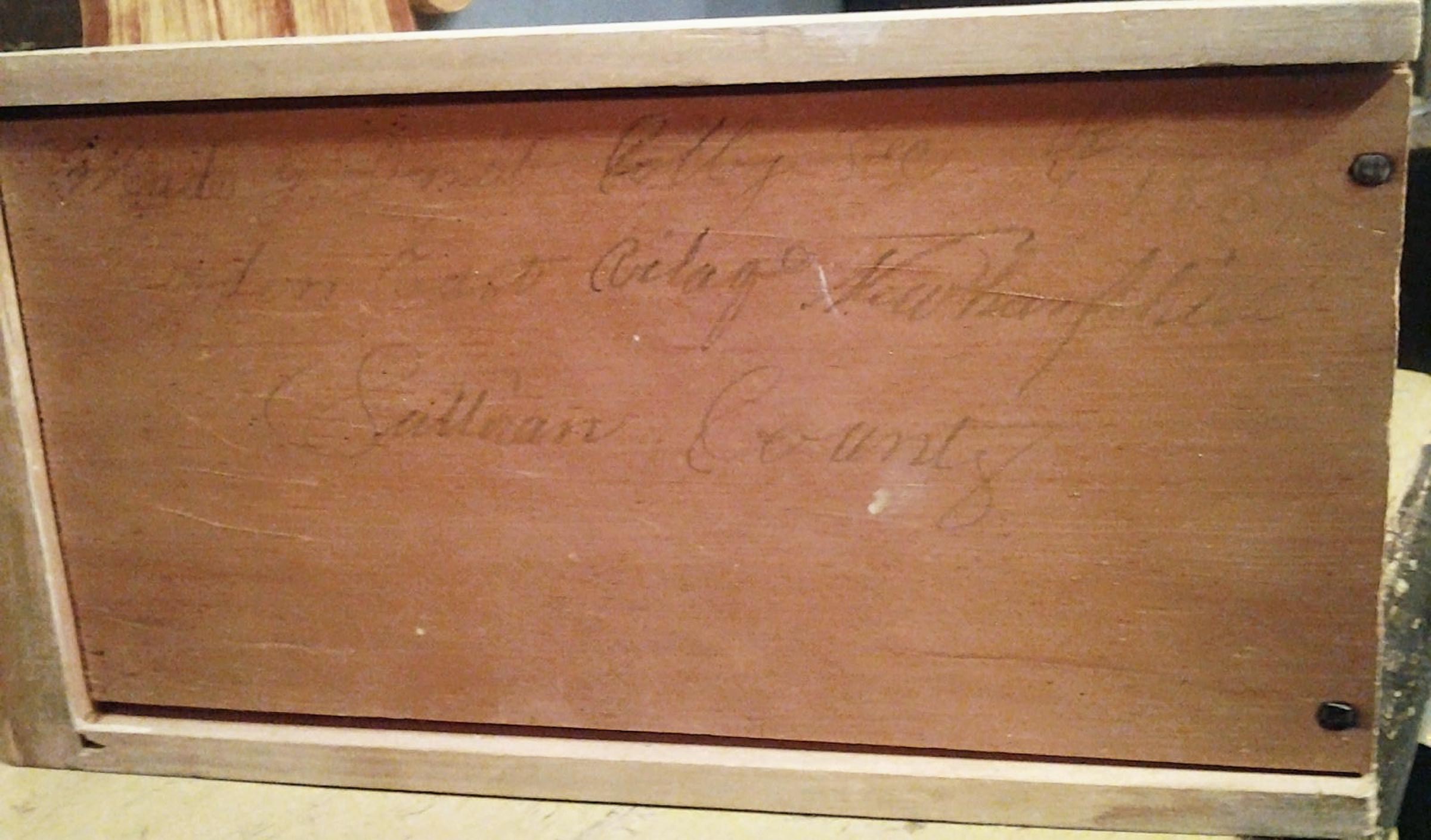

The possibility that Martin Bullock made all of the other dressing tables with galleries in Sullivan County was discounted with the appearance of one example inscribed on an upper drawer “Made by David Colby Dec. 4th 1835 / Croydon East Vil[l]age New Hampshire / Sullivan County” (Figs. 16a, 16b).12 Croydon East Village was the former name of present-day Croydon. Two men named David Colby were born near Newport in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, but no information linking them to cabinetmaking is known, leaving the identity of this David Colby unresolved.13 The inscription places Colby in Croydon, where he built a dressing table that reproduced a Harris shop design. Revealingly, after twenty-three years in business in Newport, Willard Harris sold his “Cabinet and Chair Shop, together with the whole of his stock,” as Donna-Belle Garvin tells it, to the firm of Gilmore, Hall & Dwinel in 1831, and moved to Croydon Flat, where he opened another cabinet shop. Harris remained there until 1836, when he sold the new shop and returned to Newport.14 The date of Colby’s dressing table corresponds to the period when Harris was working in Croydon Flat. The gallery on the dressing table raises the likelihood that Harris continued to produce the form there and that the two men worked together. This also strengthens the link between Harris and Bullock’s Newport bureau and dressing table.

David Colby’s signed dressing table is key in establishing the origin of other Sullivan County Fancy dressing tables with galleries. All have painted circles on the gallery drawers, Sandwich glass pulls, and stenciled compotes of fruit on the splashboards. These dressing tables were likely made in Croydon between 1831 and 1836, while Willard Harris worked there as a cabinetmaker. Harris’s activities after he returned to Newport in 1836 are unrecorded, however the probate inventory compiled after his death there in 1848 lists “25 sett [sic] dress table legs,” evidence that he continued producing dressing tables into the next decade. All of these dressing tables appear to have been made during his time in Croydon.15

In 1832, the year after Harris sold his Newport shop, Martin Bullock was in Claremont, New Hampshire, ten miles west of Newport, where he advertised “all kinds of carriage sign and ornamental painting, he will also paint in imitation of different kinds of wood, such as mahogany, oak, bird’s eye maple, &c &c.”16 Bullock may have acquired ornamental painting experience at the Harris shop, although no evidence that he painted dressing tables has been found. His 1830 bureau and his appearance in Claremont two years later mark a short period of time when he produced mahogany and Fancy furniture. Bullock left the trade and disappeared from the public record until 1847, when he was back in Grafton and was quartermaster of the Thirty-Seventh Regiment of the New Hampshire State Militia. Never married, he worked his father Grafton’s farm for the remainder of his life.17

The Fancy dressing tables made in Sullivan County, New Hampshire, are among the most stylish and innovative examples of the form from New England. They reflect a new decorative style, one that altered the appearance of many New England furnishings and interiors. The customers for this furniture lived far from large cities, but they were not culturally isolated. Their motivations for acquiring Fancy dressing tables were the same as those of their urban counterparts: a desire to own fashionable furnishings that expressed their worldliness and taste. The dressing tables also demonstrate the continuing regard for the personal needs of women, whose responsibility for managing households and raising children consumed much of each day. Other dressing table designs would replace Fancy forms, but they remained useful and prized additions to the home (Fig. 19). Sullivan County’s dressing tables show how the grooming custom documented in seventeenth-century Holland had continued in northern New England virtually unchanged.

Acknowledgments

About the Author

1 Jennifer Van Horn, The Power of Objects in Eighteenth-Century British America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017), 302; Dorothy A. Mays, Women in Early America: Struggle, Survival, and Freedom in a New World (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2004), 50.

2 Thomas Hepplewhite, The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Guide (London: I. & J. Taylor, 1794), 13, plates 72, 73; Thomas Sheraton, The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing-Book (London: T. Bensley, 1802), 397, plate 46.

3 The most thorough examination of Fancy is Sumpter Priddy, American Fancy: Exuberance in the Arts: 1790–1840 (Milwaukee: Chipstone Foundation, 2004).

4 Jane C. Nylander, Our Own Snug Fireside: Images of the New England Home, 1760–1860 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1993), 72. Spooner offered “Sign and Ornamental Painting done at short notice” in an advertisement in the Barre Gazette on November 2, 1838. I thank Tom Kelleher, Old Sturbridge Village, for this reference.

5 Edmund Wheeler, The History of Newport, New Hampshire: From 1766 to 1878 (Concord, NH: Republican Press Association, 1879), 84, 90.

6 The history of the Newport furniture industry and the Harris shop are described in Donna-Belle Garvin, “A ‘Neat and Lively Aspect’: Newport, New Hampshire as a Cabinetmaking Center,” Historical New Hampshire 43, no. 3 (Fall 1988): 202–24.

Newport’s prosperity also attracted artists. Vermont portraitist Benjamin Franklin Mason (1804–1871) painted portraits of Newport cabinetmaker William Lowell (1795–1839) and his wife, Jane Giles Lowell (1803–1872), about 1826. The Lowell portraits are at the Richards Free Library, Newport, New Hampshire. The husband and wife portrait-painting team of Samuel Addison Shute (1803–1836) and Ruth Whittier Shute (1803–1882) advertised in Newport’s New Hampshire Argus and Spectator on April 15, 1833, that they had “taken a room at Nettleton’s Hotel, where they will remain for a short time.” The “short time” turned into an eight-month stay. Wheeler, The History of Newport, New Hampshire, 102; Helen Kellogg, “Ruth W. and Samuel A. Shute” in American Folk Painters of Three Centuries, ed. Jean Lipman and Tom Armstrong (NY: Hudson Hills Press, 1980), 170.

7 Wheeler, The History of Newport, New Hampshire, 96.

8 Others include a dressing table with a gallery and a faux marble top owned by Stephen-Douglas Antiques, Walpole, MA; one in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; one sold by Christie’s, New York, Collection of Peter and Barbara Goodman, January 20, 2022, lot 201, sale 20689; one sold by Paul McInnis, Hampton Falls, NH, Americana sale, January 3, 1985; and a fourth illustrated in Antiques & The Arts Weekly, July 24, 1987, 32. I thank Donna-Belle Garvin for providing the last two references.

9 The Samuel Morse House Museum is operated by the Croydon Historical Society. Hannah Morse married in 1851, and the 1900 U.S. census for Hyde Park, Norfolk County, Massachusetts, lists Hannah, a widow, living with her daughter, son-in-law, her mother, Chloe Morse, and a servant. Chloe Morse died that year at age ninety-eight. If the dressing table descended to Hannah’s daughter, Alma, she would have been the third generation of the family to own it. “United States Census, 1900,” Accessed via FamilySearch.

10 A bureau made about 1830 by Otis Warren (1807–1867) of Pomfret, Vermont, features a similar gallery. The source of Warren’s gallery is unknown. See Jean M. Burks and Philip Zea, Rich and Tasty: Vermont Furniture to 1850 (Shelburne, VT: Shelburne Museum, 2015), 162–63.

11 A related dressing table of unknown origin with a gallery shows differences. Its overall dimensions, leg turnings, and a gallery wall composed of two boards rather than a single board differ from the Sullivan County group. Moreover, the case lacks painted reserves, and a full-width rectangular backsplash is painted with a band of foliate motifs resembling a printed wallpaper border. Despite certain design similarities to Sullivan County examples, it does not appear to be part of this group. See Ellen Kenney Glennon, “The John Tarrant Kenny Hitchcock Museum, Riverton, Connecticut,” Magazine Antiques, May 1984, 1145, plate 6.

12 I thank Bill Kelly for bringing the dressing table signed by David Colby to my attention.

13 A David Colby, Jr. (1807–1893), born in Enfield, Sullivan County, New Hampshire, moved to Ohio after his father migrated there in 1834. Whether he moved to Ohio after 1835—the year the dressing tables was made—is not known. No biographical information has been located about the David Colby born in 1801 in Sutton, New Hampshire, in adjacent Merrimack County. Interestingly, another cabinetmaker who worked for Harris, Horace Ellis (1807–1872), was also born in Sutton. Ellis signed a bureau without a gallery “Made by H Ellis / Newport N H” and “Horace Ellis, 1832.” Ellis made the bureau a year after Harris sold his shop to the firm of Gilmore, Hall & Dwinel. See New Hampshire Historical Society, Plain & Elegant, Rich & Common: Documented New Hampshire Furniture, 1750–1850 (Concord: New Hampshire Historical Society, 1978), 134–35; and Wheeler, History of Newport, New Hampshire, 96.

14 Garvin, “Neat and Lively Aspect,” 224, n. 43.

15 Ibid., 212n9.

16 Ibid., 212.

17 G. Parker Lyon, The New-Hampshire Annual Register, and United States Calendar, For the Year 1847 (Concord: G. Parker Lyon, 1847), 76, 91. David Harris also left the ornamental painting trade, becoming Newport’s coroner in 1839, deputy sheriff in 1841, and the town’s jailer in 1847. Jacob B. Moore, The New-Hampshire Annual Register, and United States Calendar, For the Year 1839 (Concord: Marsh, Capen and Lyon, 1839), 63; Asa Fowler, The New-Hampshire Annual Register, and United States Calendar, For the Year 1841 (Concord: Luther Hamilton, 1842), 67.