The Beardsleys and the Beardsley Limner: Beyond Likeness

Author’s Note

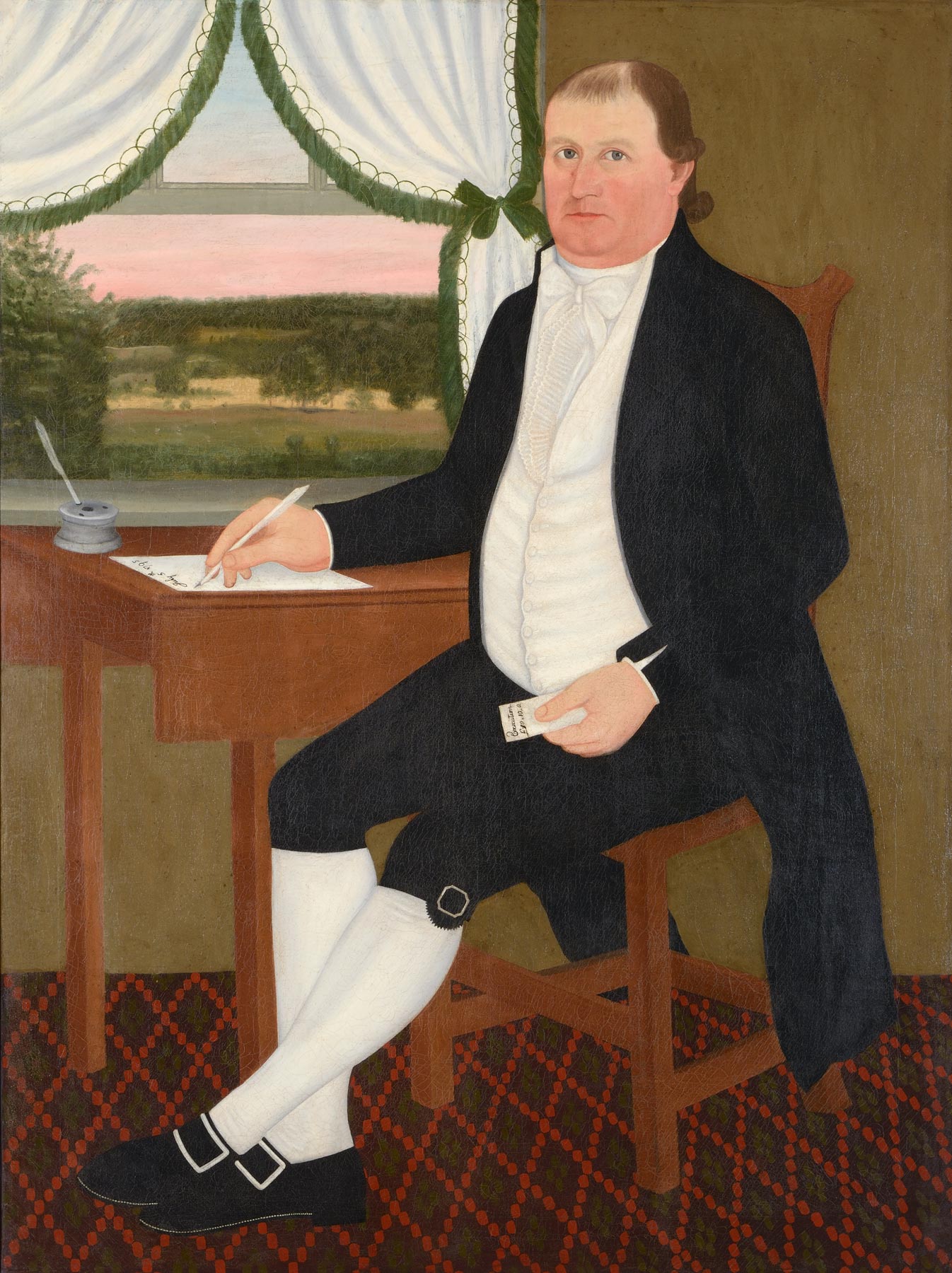

By 1784, the year after the American Revolution ended with the Treaty of Paris, Dr. Hezekiah Beardsley (1748–1790) and his wife, Elizabeth Davis Beardsley (1749–1790), moved from Hartford, Connecticut, to coastal New Haven, where Dr. Beardsley operated a drugstore in their home on Chapel Street, a few blocks from Yale College.1 Shortly before their early deaths, just weeks apart in 1790, Hezekiah and Elizabeth had their portraits painted (Figs. 1, 2). The handsome likenesses articulate the aspirational idealism among Americans during the early national period, both in the sitters’ self-fashioning and the artist’s creative invention. These qualities have rendered the portraits touchstones of American folk art since they were donated to the Yale University Art Gallery in 1952.

This essay revisits the paintings, examines the history of their reputation, and looks ahead to directions for future study. Among other things, it encourages a narrower scope of attribution of artworks to the maker of the Beardsley portraits, who remains widely identified as the Beardsley Limner (active c. 1785–1800). The need for tightening the standard of attribution derives from the diminishing confidence and quality of more recent attributions as well as erosion by association of the significance and meaning ascribed to the Beardsley portraits themselves. Hewing to the artist’s primary works encourages and enables more intensive, confident study. Examining the culture that created these central, ambitious portraits expands appreciation and understanding of the paintings among their peers in the front rank of American vernacular painting. By prioritizing the Beardsleys and their closest neighbors, a fuller, more vivid picture of the artist’s project emerges.

The Beardsley Portraits

The Beardsley portraits bear scrutiny in both quality and complexity. In Hezekiah Beardsley’s portrait, the sitter’s poised equanimity is concentrated in his impassive facial expression, but is also manifested in his portrait’s broader aspects, from its limited green and gray palette to its disciplined geometries. Exceptionally personable and individualized, Hezekiah’s figure is neither overwhelmed by its environment, despite the composition’s unusually expansive width, nor overshadowed by his fine clothing, despite its occasional visual animation, as in the patterning of his silk waistcoat. Throughout the painting, the artist balances fine, anecdotal details with larger effects, addressing the priorities of individual resemblance and cultural symbolism.

The Beardsley Limner is a conceptual painter. The artist relies on remarkably contrived ideas of representation and composition, rather than academic conventions of visual perspective or descriptive naturalism. These strategies are deliberate and exceptionally harmonious, as in the manner in which Hezekiah’s bent right elbow and extending left arm repeat the forms of the swag and fall of the green window dressing. Likewise, his seated body and turned legs repeat the right angle of the window frame that neatly divides the composition into quadrants. This geometry defines the primary structural features of the painting and disciplines its organization, offering just one—albeit a central one—of the artist’s conceptual tools to construct both symmetry and rhythm.

Hezekiah’s penetrating gaze is the focal point of his portrait. While the sitter’s brows are loosely swept and smoothed with dramatic effect, his eyelashes are separately painted, each short, black lash moving away from the sitter’s near-black irises. The effect of the delicate outline and lashes is similar to eyeliner, emphasizing the near black-and-white contrast within the eyes themselves that dramatizes his gaze. Although the artist consistently depicts his sitters with their faces slightly turned away from the picture plane, the contrasting frontality of the sitters’ eyes creates an uncanny impression of visual concentration and engagement, rather than what ought to read as awkwardness of recession. Given the amount of effort invested by the artist in portraying both Hezekiah’s crisp individual eyelashes and sweeping brows in dramatic juxtaposition, the intention to draw attention to the sitter’s eyes is clear and purposeful.

Light serves a defining function in the painting. Both shadows and highlights are often inconsistent with the apparent single source coming from outside of the composition, above the viewer’s left side, while no light comes from the window within the painting. Highlights are applied to lead the viewer’s attention and create emphasis. The left-hand page of Hezekiah’s journal of “extracts” from his reading is brightly illuminated and legible, at least in its heading. Similarly, the sitter’s face and collar are keyed far beyond the generally dark tone of the interior, as are his bright socks, which keep the movement of his legs to one side coherent. The highlights of the portrait substantially record its story and move the viewer’s eye, drawing forward emergent physical volumes that are haloed by shadowed contours.

Hezekiah is depicted at leisure, reading a book and taking notes, but the book is closed and only its spine is visible, identifying it as the third volume of Edward Gibbon’s History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Gibbon’s newly published fourth and fifth volumes are stacked unceremoniously on the table. But where are the rest of the doctor’s books? His estate inventory identifies dozens, though Gibbon was not among them. Portraits of the period consistently place scholarly sitters in front of their bookcases, but Hezekiah is posed by a window, presumably so that he could read more easily by daylight. By the omission of other reading material, the emphasis on these particular books grows, as does the doctor’s act of taking notes from them, demonstrating active attention. Their fine leather bindings with gold lettering are impressive in both quality and mass, quite literally weighty. In a portrait as restrained as this one or the one of Elizabeth Beardsley, which also prominently features her reading a specific text, such calculated emphasis is unmistakable.

In contrast to Hezekiah’s warm complexion and visual engagement, Elizabeth’s slightly wan, porcelain face exhibits guarded neutrality, setting a different tone and framing different themes that are elaborated in the rest of her portrait. Her features exhibit an extraordinary investment and refinement on the part of the artist and invite speculation. In particular, her doe eyes are alert and concentrated, but in contrast to her husband’s appraising look, they lend an air of disciplined intelligence and control to her demeanor and offer a sense of vibrant inner life.

Elizabeth’s molded features are surrounded by an elaborate ring of white lace, encompassing a multilayered bonnet atop her head and a broad collar circling her neck, which is further reiterated by her gathered forearms. These exaggerated, stylized bright whites, alternating with her black hair and a black lace shawl, center attention on her face and magnify it physically to the same scale as the window she sits beside. In combination with the artist’s drastic reduction of her body’s physicality and volume, exemplified by her tightly cinched white belt, the painting’s visual emphasis resides in her face, where her character, rather than artifice or materialism, is paramount.

Layering is a recurring motif in the portrait of Elizabeth, one that intimates both containment and complexity. The sitter’s hair is visible through the outermost fringe of her bonnet; the neckline of her dress is visible through her collar; her left forearm is visible through the cuff of her sleeve; the fruit on the table is visible through its openwork basket; and even the next page of her book is revealed by her left index finger. These contrast with the opacity of forms and materials in the portrait of her husband. The flowers in the enclosed garden visible through the window and held in her right hand offer an analogy to the layering theme. Like the many-petalled flowers, the elaborate pleats and gathers in Elizabeth’s clothes adopt abstract rhythms that are of greater interest for their patterns than for the way they define the sitter’s body. Even the elegant coils of her black hair and their wispy, scumbled ends appeal more for their design than for their description of actual hair.

Relationships are a central component of Elizabeth’s portrait. These are perhaps most literally represented by the miniature portrait of a man—possibly her father or a brother, as he does not resemble her husband—that she wears from a ribbon around her neck and by the loyal gaze of her dog sitting under the table. The relational quality of the painting extends further, however, to the way in which the flowers in the domestic garden outside her window correspond to the small pink flower in her hand—also miniaturized. Elizabeth is depicted drawing the benefits from a mature garden, echoed in the ripe pears and apples (and possibly peaches) visible in her tabletop basket. These fruits have often been interpreted as symbols of a fertility the Beardsleys did not share: they had no children, but instead raised a niece, Sarah Davis, as their own. Mrs. Beardsley’s relationships within and beyond the space of the room in which she sits create a human, natural, and intellectual network that extends far beyond her tightly picketed garden wall.

The portraits of Hezekiah and Elizabeth Beardsley were created in tandem and they function in dialogue. While there are evident contrasts, not least in décor, the two paintings are organized in answering poses and configuration, as if they were sitting opposite one another at the same table, when clearly they are not. Their tables are different in form and style; their windows face different views and are framed by different curtains. They do, however, appear to be sitting in identical green high-backed Windsor armchairs, a set of which is described in Hezekiah Beardsley’s estate inventory.2 Notably, each canvas has also been extended laterally toward the other by about eight inches, expanded on the side of the compositions where their respective windows are depicted. Both figures would otherwise have been centered in their respective compositions, but are instead shifted to bracket their shared composition. The effect is to expand the symbolism of both paintings and open the sitters’ worlds beyond their windows. In many ways complementary, the visual logics of these pendant paintings are mutually referential and reinforcing. Despite their differences, the paintings are in direct, mirror-like contrast, opposite sides of the same experience. In aesthetic terms, they also offer a sense of the artist’s range of standard deviation: how and why the painter adapted between works.

History of the Beardsley Limner

The regularity with which the Beardsley portraits have been investigated since the 1950s is a striking testament to their durability and versatility. As the tools and questions of art history have evolved over the decades, the Beardsleys have continued to offer new prospects, and the promise of their future study remains bright. Each new interpretive method applied to the Beardsley portraits has contributed to our understanding of both the artist and the sitters and kept pace with the wider field of American folk art. A survey of the major studies of the Beardsley portraits provides a sense of the arc of their appreciation and lays the foundation for a new generation of scholarship.

Just a year after the Beardsley portraits were donated to the Yale University Art Gallery in 1952 by Gwendolen Jones Giddings, who had received them by indirect family descent, they were first published in the Connecticut State Medical Journal, a reflection of their donor’s initial offer of the paintings to Yale Medical School’s library as depictions of one of New Haven’s earliest physicians and his wife.3 The article, “Portraits of Doctor Hezekiah Beardsley and His Wife, Elizabeth,” was written by the university’s medical librarian, Frederick G. Kilgour, who understandably concentrated on Dr. Beardsley’s professional biography and wrote little about the portraits as artworks beyond a summary description of them as “good examples of the so-called school of American primitive painting.”4

Kilgour recalled Dr. Beardsley’s work in pediatric medicine, including a lecture for the recently founded Medical Society of New Haven County in April 1788, later published, on a fatal “Case of a Schirrus in the Pylorus of an Infant” who had been his patient in Southington, Connecticut. The child was unable to digest food properly, and Dr. Beardsley’s autopsy revealed the cause as a hardening of the opening between the child’s stomach and her intestine, now known as pyloric stenosis. Kilgour observed that Dr. Beardsley was not the first to discover the condition, which had been identified in earlier publications in Europe, but that he likely recognized it independently and was the first to describe it in America, which he did with remarkable accuracy and detail despite his lack of academic medical training. Kilgour credited the “high level of medical practise [sic] in Connecticut in the last half of the eighteenth century,” which Dr. Beardsley represented, as the basis for the later creation of the Yale School of Medicine, in 1810, a community of physicians “anxious to maintain and increase the proud traditions of their profession.”5 To Kilgour, the interest of the Beardsley portraits was in the perspective they offered into the culture of early medicine. Viewed in that light, it seems peculiar that Hezekiah is not depicted as a practicing physician or an apothecary, but at leisure, reading Gibbon.

The first characterization of the Beardsley Limner came in Nina Fletcher Little’s 1957 introduction to Little-Known Connecticut Artists, 1790–1810, published as a special issue of the Connecticut Historical Society Bulletin to accompany an exhibition of the same title held at the historical society during the ensuing winter.6 As Little’s title suggests, her goal was “to invite critical comment, add information, and stimulate interest” in the group of artists she drew together, most of whom remained anonymous.7 Of special note were two unknown painters of large portrait pairs—the Beardsley and Eldredge Limners—whose work justified the project in Little’s eyes, and who, she concluded, “are worthy of a high place in American provincial art.”8 The Eldredge Limner’s prominent, full-length 1795 portraits of James and Lucy Gallup Eldredge of Brooklyn, Connecticut (Figs. 3, 4), share a sense of concept and ambition with the Beardsley portraits. The Eldredge portraits were donated to the Connecticut Historical Society and later attributed to John Brewster, Jr. (1766–1854), whose early work, like the Beardsley Limner’s, demonstrates a strong influence of the work of Ralph Earl (1751–1801), who had been active in New Haven in the mid-1770s.

Little’s essay attributed six paintings to the Beardsley Limner and relied on them to describe the artist’s work as “outstanding for his use of color and for the clarity of his architectural backgrounds.”9 Little provided few specifics to link the paintings of “this distinguished group,” of which four depict children—Charles and Joseph Wheeler and an unknown girl (possibly another Wheeler, the boys’ older sister, Sally) and a third boy. The Beardsleys are the only adults in the group, whose portraits Little connected with those of the children for similarities in “pose, contour of face . . . oddly highlighted hair, and the manner of painting costumes and accessories.”10 Little’s project was, as she described, an opening. Her work provided a starting point for two important rounds of later research and preliminary criteria for further attributions.

The most intensive study of the Beardsley Limner was associated with the 1972 exhibition The Beardsley Limner and Some Contemporaries: Postrevolutionary Portraiture in New England, 1785–1805, organized by Christine Skeeles Schloss, then a graduate student at Yale, and Tom Armstrong of the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Collection in Williamsburg, Virginia, and accompanied by a catalog that Schloss authored.11 Schloss and Armstrong convened the fourteen paintings then attributed to the Beardsley Limner and placed them in the context of the artist’s New England contemporaries, including both Earl and Brewster. According to director Graham Hood’s introduction to the catalog, the project was intended to initiate a series of exhibitions that would explore regional American folk art traditions, identify individual artists, and evaluate folk art’s quality.

Schloss set the Beardsley Limner into a social and historical context, particularly the revival of middle-class portraiture in the aftermath of the American Revolution. She set Earl and Winthrop Chandler (1747–1790) as the benchmarks of practice in Connecticut and Massachusetts for artists like the Beardsley Limner. Building on Little’s research, Schloss sought to identify and enumerate more fully the signature characteristics of the Beardsley Limner’s “formula,” including the consistent three-quarter view of his sitters’ faces; the regular shape of his sitters’ cheeks, noses, and upper lips; and “the symmetrical, almond-shaped eye” that she found their “most striking and characteristic feature.” She also described the awkward depiction of volume in the sitters’ clothing and bodies, their distinctive position in space, as well as their “gracefully proportioned hands.”12

Schloss initiated a chronological record of the lives of the artist’s known sitters to describe the artist’s practice through time. She added connective links to contemporaries, notably Christian Gullager (1759–1825), who painted a portrait of Dorothy Lynde Dix, mother of at least three, and possibly four, of the Beardsley Limner’s sitters, which enabled Schloss to contextualize the artist’s multiple influences.13 The exhibition included works by ten of the Beardsley Limner’s contemporaries in order to foreground the presence of informal education in the study of other artists’ works by self-taught painters like the Beardsley Limner.

In an article for The Magazine Antiques in 1984, Colleen Heslip and Helen Kellogg collaborated on the first effort to associate an individual—Connecticut pastellist Sarah Perkins (1771–1831)—with the artist identified up to this point only as the Beardsley Limner. Comparing both style and social network, Heslip and Kellogg made the case for linking the two artists’ work across media—pastel drawings by Perkins and the Beardsley Limner’s work in oil paint—on the evidence of the Perkins family’s educational ties to Yale and professional associations in the field of medicine, vehicles for recruiting her commissions. Although Perkins lived in Plainfield, Connecticut, near the eastern edge of the state, her relatives, including four of her five brothers, attended Yale, which may have brought her to New Haven and into the Beardsleys’ acquaintance. Perkins’s father, Elisha Douglas, was also a prominent physician, as were a number of other male relatives, and he traveled often to promote medical tools of his invention, which may have introduced him to the Beardsleys. The article relies on speculative links—the possibility that Perkins’s father arranged commissions while on his travels or that children from distant parts of New England attended her neighboring Plainfield Academy—to make a circumstantial case for Perkins’s access to the sitters in the Beardsley Limner’s portraits.14

Stylistically, the authors cited Schloss’s work as the basis for their study of the Beardsley Limner, beginning with the almond-shaped eyes and including her general list of signature stylistic criteria, to which they added the graduated lighting across the backdrops of the portraits, as well as recurring qualities in the sitters’ hairstyles and clothing.15 Perkins’s rediscovery had followed a similar trajectory to the Beardsley Limner’s from the 1950s on, and the authors relied on the foundational work of William Lamson Warren for their study of Perkins.16 The stylistic association of the two artists’ works relied on broad assumptions, including a “similar level of maturity” in Perkins’s pastels around 1789 and the Beardsley portraits, although this would have an eighteen-year-old Perkins, near the beginning of her career, creating the Beardsley portraits.17 A comparison of Perkins’s portrait of Alpheus Hatch (Fig. 5) with that of Hezekiah Beardsley suggests a considerable contrast in effort and ability, while an indifference to color in the former work is at odds with that distinguishing attribute of the Beardsley Limner. Hatch’s clothes seem to peel back to parallel the picture plane and expand the mass of his chest to fill space, whereas Dr. Beardsley’s jacket moves in gracious undulations, and his body seems to retreat from the picture plane.

The attribution of the Beardsley Limner’s works to Perkins has not been widely adopted by museums. In her catalog of American folk art in the collection of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, Deborah Chotner concluded that “while some stylistic similarities exist between the two, there are sufficient differences to raise questions about this identification.”18 Nevertheless, the comparative study of Perkins’s work and life experience with the Beardsley Limner’s milieu is illuminating and offers a productive record of the kind of network of relationships that the Beardsley Limner may have shared.

In the most recent study of the Beardsley paintings, in 2008, Robin Jaffee Frank highlighted the vibrant intellectual and devotional world of the sitters and the dynamics of their marriage as recorded in the respective readings shown in the paintings.19 Frank newly identified the book in Elizabeth’s hand as James Hervey’s two-volume Meditations and Contemplations (1746), which was recorded in their library in Hezekiah’s estate inventory of 1790. The book is shown open to the chapter “Reflections on a Flower-Garden,” a direct reference to the subject shown outside her window and a metaphor for the spiritual order, modesty, and consideration of salvation New Light Calvinists like Hervey espoused for women.20 In Frank’s view, the portraits depict the sitters’ inner lives and their life together, as two people contemplating their own mortality as well as the future of their young nation, highlighted by Hezekiah’s volumes of Gibbon. The portraits’ sensitivity to the Beardsleys’ spiritual life has opened a promising new avenue of investigation.

Attribution and Meaning

Early discussion of the Beardsley Limner focused on discerning the artist’s work, separating it from that of other artists in New England during the same period. The primary metric for attribution was comparison with the Beardsley portraits themselves; they set the standard. The two paintings suggested the integrity of vision of a distinct maker and a quality of work worth knowing more about.

As time passed and research continued, other artworks came into view that shared characteristics either with the Beardsleys or with the four other paintings that Nina Little first identified. But the attributes used to evaluate newer arrivals were broad, especially those related to infelicities of volume and space that are common in folk art. Connecticut painters were naturally influenced by the same constellation of nearby peers whose works they had access to for study and emulation, and they portray sitters in the fashion of clothing and hairstyle of their shared moment.21 These cannot be the basis for attribution.

Because no other painting currently attributed to the Beardsley Limner approaches the Beardsley portraits in quality, complexity, or significance, the artist’s identification with the paintings remains critical—anything attributed to the artist must connect with the project that produced these two paintings. Frank’s research has unveiled layers of intellectual and religious character that visual description—three-quarter pose, almond-shaped eyes, and so forth—does not capture. If made by the same person, other works must share the Beardsley portraits’ intelligence and worldview and demonstrate the Beardsley Limner’s habitual practices.

Since the late nineteenth century, connoisseurship has been defined by the work of the Italian critic Giovanni Morelli (1816–1891), to whom insignificant details, rather than practiced ones, uniquely revealed the presence of the artist’s hand, because they illustrate idiosyncrasy. Morelli offered a vehicle for attribution that has proven a lasting paradigm, in which, as summarized by Edgar Wind, “an artist’s personal instinct for form will appear at its purest in the least significant parts of his work because they are the least labored.”22 Morelli found that the studio devices of composition, proportion, color, expression, and gesture are most often manifested through ingrained repetition of training or imitation, whereas in details—an earlobe or a fingernail—the artist reveals personal solutions.23 In these nuances, alongside the Beardsley portraits’ visual intelligence, the artist can be recognized.

Comparison of Elizabeth Beardsley’s portrait with the portrait of Harmony Child Wight (Fig. 6), for example, offers a starting point for a different order of discussion around attribution. The translucency of Wight’s collar and the fringe of her bonnet as well as the treatment of the movement and wisp-like ends of her hair resonate with Elizabeth’s portrait. Likewise, the angled curtain behind Wight, which reveals the distant landscape and parallels the front edge of the bonnet that exposes her face, creates an analogy of the portrait as a window into the sitter’s character. The style of the two paintings is not identical, as Wight’s is more freely painted and suggestive in its characterization of the sitter, but they share the attributes that Little and Schloss—who first attributed the Wight portrait—acknowledged, as well as a degree of metaphorical imagination not found in many of the works attributed to the Beardsley Limner.24

Aspects of the Beardsley portraits define the criteria for other works securely sharing their attribution. Other works should not be associated with the artist’s aesthetic and stylistic practices without conditional phrasing. Tightening the frame around the artist’s central practice enables meaningful consideration of variation between sitters and over time. Rather than a spiraling dilution of identity, the process becomes more deliberate, conscious, and purposeful when the core group of works remains clear. Placed at the center, the Beardsley portraits find more interest and relevance than they do in relation to works marginally attributed to the artist.

By these criteria, the Beardsley portraits share more in character and aspiration with the paintings of Earl, especially his early portrait of Roger Sherman (Fig. 7), from around 1775, also painted in New Haven, where Sherman lived and served both as treasurer of Yale and as a representative to the Continental Congress. Sherman’s dour character is remarkably encapsulated by this idiosyncratic portrait, which the neighboring Beardsleys and the artist who painted them must have known. The severity of Earl’s portrait—his focus on facial expression, limited palette, and striking sense of likeness, including the awkward peculiarities of the seated figure’s arrangement in space—connect with the portrait of Hezekiah in particular. The Sherman portrait is Beardsley’s neighbor in every sense, down to his green Windsor chair. Likewise, there are revealing echoes of the portrait of Elizabeth in Connecticut artist Winthrop Chandler’s striking contemporary portrait of Anna Paine Chandler (Fig. 8), the artist’s sister-in-law, from around 1780. The painting’s crisp, austere representation of Chandler’s face resembles Elizabeth’s in essential ways, both in their insistent clarity of likeness and their balance with the decorative flourishes in their surrounding space. However, Elizabeth preserves a symmetry with the interior in which her husband appears, while Chandler’s drapes have a life of their own. These comparisons to works by other artists benefit understanding of the Beardsley portraits more than comparison to the paintings less securely attached to the same artist.

The Beardsley portraits invite further research in ways that have only been recently revealed. Frank’s discovery of the Hervey book in Elizabeth’s portrait has added dimension to the paintings’ portrayal of the sitters’ appearances by expanding into their historical and religious imaginations. Viewers are now invited to contemplate more fully the legible and complementary textual components of the paintings—previously only possible through Hezekiah’s reading of Gibbon’s Decline and Fall—in the contexts of both their domestic experience and natural environment. The fullness of the paintings’ presentation of their sitters’ distinct characters offers a rich source for additional investigation of their lives and thought. Among other interpretive questions that Frank’s work frames by parallel construction is what passage of Gibbon Hezekiah may be reading. Volume three is clearly portrayed in his hand, and his finger marks a page midway through.25 A possible passage could be Gibbon’s discussion of the circumstances of Britain’s independence from the corrupt and indifferent Roman Empire in AD 409, a notable prefiguration of the American Revolution. Gibbon’s historical epic was, and remains, a study of religious as well historical significance that invites, as does Elizabeth’s Hervey reading, further research into the Beardsleys’ church affiliation and belief. Are both paintings records of religious dissent? If so, what is the role of these portraits as affirmations of their beliefs?

As the basis of study of the Beardsleys has changed over time, new questions have also arisen. Of particular note today, in an era of global commerce, are Hezekiah’s advertisements in local newspapers soliciting animal furs during the same period, the late 1780s, when he also advertised the newest medicines and drugs for sale from London and Amsterdam.26 Why was a New Haven doctor looking for pelts? Was he bartering abroad for his inventory of new medicines with furs brought down the Quinnipiac River? The trade places him, and the landscape outside his window, in an Atlantic marketplace of goods and people through the port of New Haven. In addition to the clothes and furnishings visible in the Beardsley portraits, the posthumous inventory of their home enumerates every aspect of their material experience, inviting study of their place in the Atlantic market in combination with Hezekiah’s business interests.27 Despite being known for decades, the Beardsley portraits offer continued promise to open our understanding of their world ever wider.

About the Author

1 Biographies of Hezekiah Beardsley disagree on the date of the Beardsleys’ move from Hartford. Beardsley bought a home and property on the south side of Chapel Street in New Haven, midway between Church and Orange Streets, in January 1782. He opened a drugstore with his brother Dr. Ebenezer Beardsley directly across from Yale in April 1782, but he advertised a similar business in Hartford until December 1783. The best-researched biography of Beardsley appears to be Walter R. Steiner’s of 1934, which reports: “In 1784 [Beardsley] removed to New Haven and in May of that year became an original member of the New Haven County Medical Society.” “Doctor Hezekiah Beardsley, 1748–1790,” Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine 6, no. 4 (March 1934): 369. An earlier version appeared in Howard A. Kelly and Walter L. Burrage, eds., American Medical Biographies (Baltimore: Norman Remington, 1920).

2 “6 Green Windsor chairs high backs,” listed in “Inventory of Doct. Hezh. Beardsley’s Estate, Recd. July 19th, 1790,” Connecticut Probate Court (New Haven District), Register of Probate Records, vol. 16 (1787–94), 46.

3 Frederick G. Kilgour, “Portraits of Doctor Hezekiah Beardsley and His Wife, Elizabeth,” Connecticut State Medical Journal 17, no. 4 (April 1953): 298–300.

4 Ibid., 298.

5 Ibid., 300.

6 Nina Fletcher Little, “Little-Known Connecticut Artists, 1790–1810,” Connecticut Historical Society Bulletin 22, no. 4 (October 1957): 97–128.

7 Ibid., 98.

8 Ibid., 103.

9 Ibid., 99–100.

10 Ibid., 100.

11 Christine Skeeles Schloss, The Beardsley Limner and Some Contemporaries: Postrevolutionary Portraiture in New England, 1785–1805 (Williamsburg, VA: Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Collection, 1972). Schloss also published a version of this catalog essay as “The Beardsley Limner,” The Magazine Antiques, March 1973, 533–38. Schloss first wrote about the artist for a student paper submitted January 28, 1970, a copy of which is in the object files of the Yale University Art Gallery. She also revisited the subject in 1980 in the exhibition catalog American Folk Painters of Three Centuries, ed. Jean Lipman and Tom Armstrong (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art), 13–17.

12 Schloss, The Beardsley Limner and Some Contemporaries, 12.

13 Ibid., 12–13, cat. nos. 10–13, 21.

14 Colleen Heslip and Helen Kellogg, “The Beardsley Limner Identified as Sarah Perkins,” The Magazine Antiques, September 1984, 548–65. A file of family records that may have helped to substantiate the article’s thesis and identified Perkins as a painter in oils was lost. 557.

15 Ibid., 550.

16 William Lamson Warren, “Connecticut Pastels, 1775–1820,” Connecticut Historical Society Bulletin 24, no. 4 (October 1959): 101–7. The initial attribution to Perkins relies on a single work, Catherine Pitkin Perkins (1790, private collection), which bears a label identifying the artist. Heslip and Kellogg, “The Beardsley Limner Identified,” 555, plate 7.

17 Heslip and Kellogg, “The Beardsley Limner Identified,” 554.

18 Deborah Chotner, American Naïve Paintings (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1992), 14.

19 Robin Jaffee Frank, “The Beardsley Limner,” in Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness: American Art from the Yale University Art Gallery, ed. Helen A. Cooper (New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 2008), 36–38. Frank here extended her earlier study of the paintings in her exhibition catalog Love and Loss: American Portrait and Mourning Miniatures (New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 2000), 22–31.

20 Much of New England, including New Haven, was afire with religious revivalism and dissent during the eighteenth century, beginning with the Great Awakening, led by New Light minister and Yale alumnus Jonathan Edwards (1703–1758) in Northampton, Massachusetts, during the 1730s.

21 On the emergence of a Connecticut style of portraiture, see Elizabeth M. Kornhauser and Christine S. Schloss, “Paintings and Other Pictorial Arts,” in The Great River: Art & Society of the Connecticut Valley, 1635–1820 (Hartford, CT: Wadsworth Atheneum, 1985), 137–38.

22 Edgar Wind, “Critique of Connoisseurship,” in Art and Anarchy (London: Faber and Faber, 1963), 40.

23 Although Heslip and Kellogg invoke “unconscious details” in the inventory of stylistic identifiers of Perkins’s work, they point to attributes of space and volume as well as the shape of the figures’ almond eyes and lips, all of which Morelli identified as aspects of conventional practice. “The Beardsley Limner Identified,” 550.

24 Historian Carlo Ginzburg has recognized the value of a “convergence” of disciplinary approaches to the connoisseurial study of unidentified artworks. “Vetoes and Compatibilities,” Art Bulletin 77, no. 4 (December 1995): 534–36.

25 Schloss considered the question of which edition of Gibbon Hezekiah may be holding, partly as a vehicle to open the question of the paintings’ date. Although their scale is perhaps slightly skewed, the painting appears to show the original quarto edition in five volumes (completed in 1788), with volume numbers prominently shown on the Moroccan bindings. Schloss, The Beardsley Limner and Some Contemporaries, 20.

26 Hezekiah ran regular advertisements in the Connecticut Journal and the New-Haven Gazette, among other Connecticut newspapers, from April 1787 until his death in May 1790. He typically ran two separate ads, one selling medicines, and the other offering to purchase furs. Some of the medicines and various other imports for sale and types of fur sought for purchase are enumerated in selected advertisements and listed in Steiner, “Doctor Hezekiah Beardsley, 1748–1790,” 370–71.

27 “Inventory of Doct. Hezh. Beardsley’s Estate,” 44–51.