Hooked Rugs

at Henry Francis du Pont’s Chestertown House

Cynthia Fowler

Henry Francis du Pont’s summer home in Southampton, Long Island, New York, called Chestertown House, was an important precursor to his renowned Winterthur estate in Delaware. Built in 1925, Chestertown House was envisioned by du Pont to be “an American house,” which he decorated with an exceptional collection of American furniture, American art, and Americana—most notably hooked rugs.1 Du Pont bought the bulk of his rugs in the 1920s and displayed them throughout Chestertown House, where they could be found in every room.

Du Pont considered his collecting habits to be an expression of his creativity. In 1952, he reflected, “Each individual who collects anything of a serious nature thinks in increasingly creative terms, almost as if his growing collection were a kind of artistic medium.”2 Although scholars have examined the development of du Pont’s color aesthetic in his choice of other decorative arts, little attention has been paid to its expression in his rugs. But throughout Chestertown House, du Pont actively explored the expressive possibilities of color inherent in these textiles and employed them to add significantly to the color scheme of each room.

Du Pont himself explained that his early training in “colors and proportions” began with museum visits.3 A 1923 visit to Electra Havemeyer Webb’s Brick House in Shelburne, Vermont, provided him with his “first introduction to an early-American interior,” but he was specifically “fascinated by the colors of a pine dresser filled with pink Staffordshire plates” (Fig. 1).4 Art historian Jay Cantor explains that when it came to du Pont’s aesthetic, from the early 1920s “it was color harmony that attracted him.”5 Similarly, Denise Magnani, a specialist on du Pont’s gardens, explains that he “looked very closely at the colors of individual flowers in varying light conditions, in combination with other colors, and as part of the whole landscape . . . . He fell in love with color and its exhilarating possibilities.”6 Magnani concludes that du Pont’s color choices for the flowers in his gardens informed his color choices for upholstery, curtains, and other household textiles. The majority of rugs in his collection were floral designs providing another connection to his gardens—bursts of color and their designs inspired by the wide array of flowers.

Two individuals played significant roles in the development of du Pont’s color aesthetic. His friend Marian Coffin, who trained as a painter, worked closely with him on the development of the gardens at both Southampton and Winterthur. A research paper on Coffin explains, “The importance of color in Marian Coffin’s work cannot be overemphasized. With her painterly sensibility, she was unusually sensitive to the expressive possibilities of subtle color modulations and contrasts.”7

Henry Davis Sleeper’s color experiments, particularly his extensive use of hooked rugs, at Beauport in Gloucester, Massachusetts, also profoundly influenced du Pont.8 Sleeper’s friend Paul Hollister explained that Sleeper expressed his creativity through interior decoration. Hollister wrote, “Someone suggested that he may have been a frustrated painter, whose craving for colour and composition finally reacted into masterpieces as rooms inside houses.”9 Sleeper had developed Beauport as a showcase of his style, and American hooked rugs, located throughout his house, were an important element of that style.10 Fundamentally, what du Pont learned from Sleeper was that creative interpretation should supersede a commitment to historical accuracy. A 1924 letter from Sleeper to du Pont expresses their shared view that rooms should be expressive, or even “eccentric,” in their design.11 Regrettably, surviving letters between the two men do not include any specific advice from Sleeper on hooked rugs, but their potential as tools for creative expression was evident in both homes.

Sleeper’s Octagon Room (Fig. 2), an eight-sided dining room completed in 1921, exemplifies his use of hooked rugs. He called it his “souvenir de France,” because he had worked there for the American Field Service during World War I.12 A watercolor of the room painted in 1928 documents its appearance around the time that du Pont saw it. In recognition of the ties between America and France, Sleeper hung portraits of both the Marquis de Lafayette and George Washington and boldly added a red lacquer Chinese screen to the cultural mix.13 The paneled walls and all the other woodwork are painted a plum color so deep as to appear almost black.14 Dark paneling provided a particular challenge for Sleeper in livening up his rooms, a challenge also faced by du Pont, since many of the rooms at Chestertown House also had dark paneling. Sleeper infused the Octagon Room with color through a variety of objects, including Chinese red and gold toleware, gilt book bindings, and, as Hollister describes in his book on Beauport, “the amber glow of tiger maple furniture.”15 The Octagon Room included three hooked rugs that added significant color, most notably the vibrant array coming from the geometric starburst design of the octagonal rug in the center of the room. Sleeper was not averse to mixing rug designs; two floral rugs are juxtaposed here with the geometric one. Hollister concludes that the Octagon Room is “perhaps one of the most highly stylized, colorful rooms in America,” defined by the “controlled audacity of its color scheme.”16 He concludes that overall, Beauport is “a symphony of subtle colours.”17 While taking careful note of the important role of paint, fabric, wallpaper, and even furniture in developing color in the rooms of Beauport, Hollister makes no mention of rugs in the creation of that symphony.

Du Pont was collecting hooked rugs at a time when they were a highly fashionable form of home decoration. In a 1928 article for House Beautiful, Margaret Lathrop Law wrote of a “hooked rug mania” to describe their widespread popularity among “antique dealers, decorators and summer cottagers.”18 Hooked rugs attracted a broad range of middle- and upper-class urban consumers, who scavenged antique shops, estate sales, and craft shows searching for appealing examples.19 Wealthy collectors like du Pont and his sister preferred antique rugs, which were often pulled out of attics and other storage areas to be sold. Recently made rugs inspired by antique designs satisfied middle-class Americans; they were far less expensive and, to the untrained eye, largely indistinguishable from their antique counterparts. Du Pont’s wealth and connections enabled him to amass an outstanding collection of antique rugs, although they became more and more difficult to find as the craze continued.

Bills and letters in the Winterthur archives document antique shops and other venues from which du Pont purchased rugs. As early as 1923, he was buying from the popular R. W. Burnham Antiques and Hooked Rugs in Ipswich, Massachusetts, which advertised itself as the “headquarters of the hooked rug industry in America.”20 A 1928 letter from Burnham to du Pont describes the difficulty of finding the high-quality antique rugs that du Pont desired. In evaluating some rugs that he was sending to du Pont, he explained, “the writer considers these rare hooked rugs much more difficult to obtain than block front pieces of furniture or savory highboys.”21 Du Pont relied on a host of antique dealers and collectors who searched for rugs for him, all of them very much aware of his taste. Rug sellers often sent pieces to him “on approval,” giving him an opportunity to examine a rug, usually sent directly to one of his homes, before he made a commitment to purchase it. The rugs he bought typically ranged between twenty-five dollars and $650.22

Smaller and lesser-known shops accessed by du Pont included Lenore Wheeler Williams in New York, Rosenbach Company in Philadelphia, Wales-Stanier Antique Shop in Wilmington, and Little Shop Around the Corner in York, Pennsylvania. He also purchased rugs at auction. In 1924, for example, he bought some from a large collection of antiques owned by George F. Ives of Danbury, Connecticut, a friend of the influential authority on early American furniture Wallace Nutting.23 Perhaps after seeing rugs that were collected in Nova Scotia by Caswell Barrie in an auction at the Anderson Galleries, du Pont reached out to Barrie about purchasing directly.24 In addition, du Pont relied on esteemed art and antique collectors, such as Charles Woolsey Lyon, a highly regarded antiquarian with a gallery in Manhattan. Lyon was also a consultant to Henry Ford and national museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. Records indicate that du Pont bought rugs from Lyon from 1924 to 1929.

Knowledge of du Pont’s interest in hooked rugs was widespread enough that individuals outside the antique and auction markets contacted him directly. During 1929 and 1930, he was in correspondence with Frederick Wellington Ayer, who made his fortune in lumber and paper production.25 Ayer explained he was not in the business of collecting rugs or antiques, writing, “I have never sold but one rug, and have no opportunity for retailing.”26 Yet somehow Ayer had amassed some 250 hooked rugs and claimed that up to a hundred of them were over a hundred years old, though he did not disclose their origins. He was, however, quick to point out their high quality, stating, “I have the best collection of New England hooked rugs that is or ever has been in the state of Maine,” which he estimated was valued at $80,000.27 Intrigued, du Pont requested that Ayer send the rugs to him on approval. Ayer chose to personally deliver the collection to Winterthur, and du Pont’s purchases totaled at least $10,000.28

Correspondence relating to du Pont’s rug purchases affirms his choices were informed by color. In 1925, for example, he sent rugs back to Stephen Van Rensselaer, who ran an antique shop in Peterborough, New Hampshire, because, as du Pont explained, “I do not like their color.”29 Du Pont returned another rug to Van Rensselaer in 1928 for the same reason. Van Rensselaer was asking $1,200 for the rug, but its high price was not the deciding factor.30 In a letter with the return, du Pont wrote, “I think the hooked rug which you were good enough to send me on approval is beautiful and I have kept it for several days trying to see if I could work out a place to use it but unfortunately I cannot seem to make the red color fit in, and therefore I have decided to return it to you.”31 Decisions like these reveal du Pont’s recognition of the important role rugs played in the color scheme of a room. Not surprisingly then, dealers approached du Pont based on their knowledge of his interest in uniquely colored pieces. For example, Robert Hall, owner of Authentic Antiques in Dover-Foxcroft, Maine, wrote to du Pont of a rug he was sending him for review, “I have taken the liberty to include a rug in the rough on account of its unusual coloring. I think it has possibilities.”32 The design of the rug was a pictorial scene of a New England homestead and included initials, presumably those of its maker. Hall suggested that the initials could easily be removed “if one so desired.” Du Pont purchased the rug after the alteration was made, apparently more interested in the rug for its color than in leaving evidence of the original artisan.33

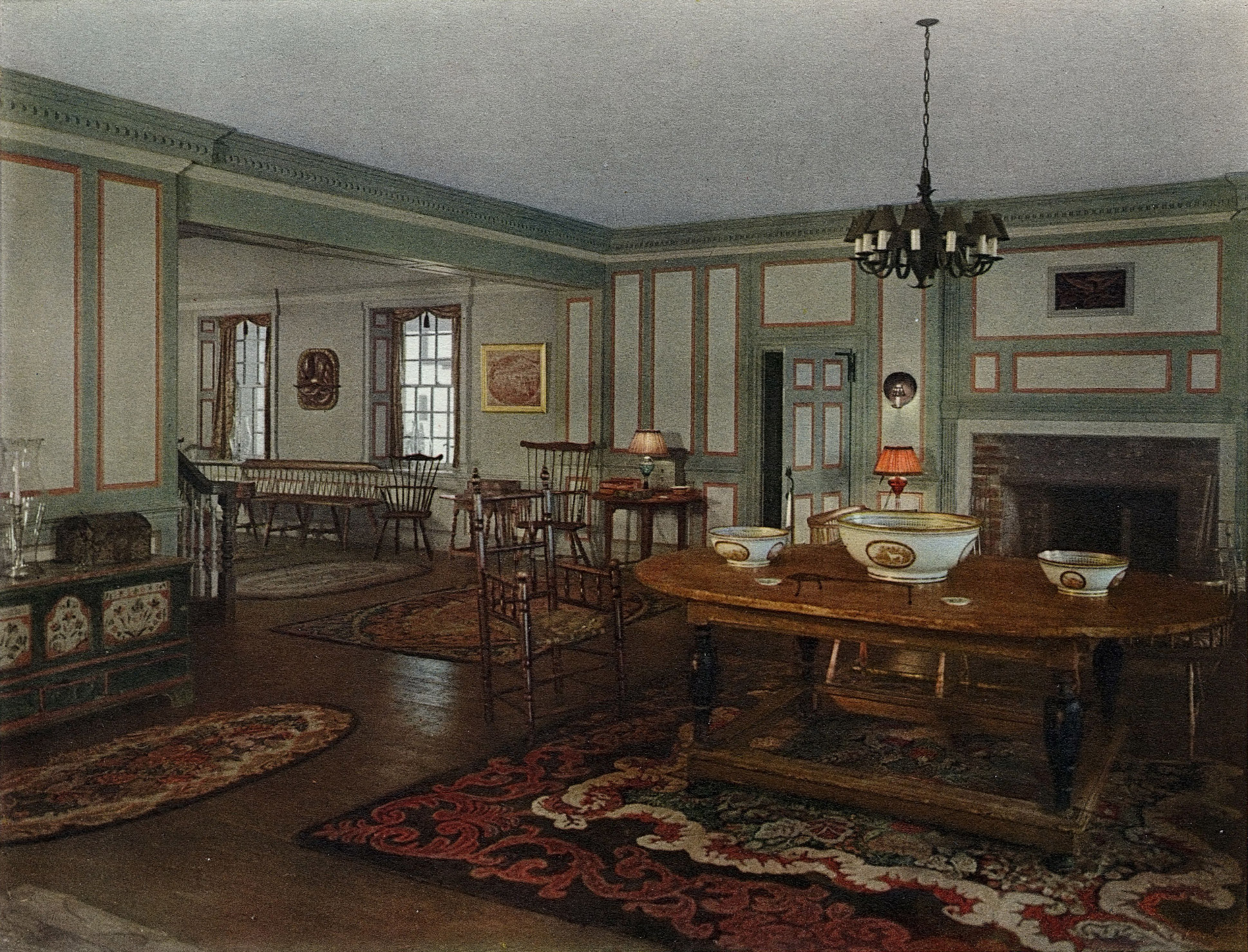

Photographs of the rooms at Chestertown House document the important role of individual rugs in adding color to the overall décor. The Living Room (Fig. 3), an otherwise dark room defined by wood paneling, is enlivened by at least four rugs. Fabric choices add color, such as a settee with mauve upholstery, but the floral rug in the center of the room contributes additional hues. A description of that rug can be found in a catalog du Pont had put together of all of the rugs at Chestertown House; the catalog consists of photographs of individual rugs along with written notes.34 The description for this rug begins, “This is a peerless and superb specimen of the finest that New England produced, both in color and design.”35 It is not surprising that such a prized rug would take center stage in the most formal room of the house. The catalog description pays great attention to the specific types of flowers in the rug and the colors that the flowers contributed to it, identifying pansies, fuchsias, roses, lilies, and morning glories “in shades of mauve, orange, pink, blue, olive, and green.”36 The rug also includes birds enjoying the vivid flowers. Another Chestertown House room decorated with floral rugs is the Pine Room (Fig. 4), and, as in the Living Room, they brighten an otherwise dark wood-paneled room.

Regrettably, many of the rugs documented in the Chestertown House photographs are no longer in the Winterthur collection. However, rugs bequeathed to Winterthur by du Pont and still held by the museum allow a closer look at the details he appreciated in all of his rugs. In a rug that Winterthur dates broadly as “nineteenth century” (Fig. 5), bursts of color come from red, blue, purple, pink, and orange flowers freely arranged around a central medallion. The medallion is also filled with flowers, with the added touch of an equally colorful bird perched on one of the flower’s branches. This rug is one of the most vibrant and freely designed in the Winterthur collection.

Although color was central to du Pont’s design aesthetic, he arranged his rugs with more than color in mind. For example, the round shape of a chandelier hanging in the center of the Living Room harmonizes perfectly with the repeated circles in the rug below. Similarly, in the first-floor hallway (Fig. 6), a rug with a diamond-shaped medallion picks up the geometry of the pediment above the doorway.37 Two rugs in the Winterthur collection are similar in design and color to this hallway rug, and one may be the exact rug at Chestertown House (Fig. 7).38 Winterthur’s records date both of these rugs between 1840 and 1860 and originating from Waldoboro, Maine. As American hooked rug expert Mildred Cole Péladeau has explained, Waldoboro rugs were known for raised three-dimensional designs that were clipped or sheared to create “a smooth, velvety texture.”39 In addition, Waldoboro rug designs are distinguished by a central oval filled with flowers, baskets, wreaths, fruit, or animals, and in this regard, these Winterthur rugs are uncharacteristic of the Waldoboro style. An excellent example of a Waldoboro rug in the Winterthur collection (Fig. 8) was donated to the museum in 1956. Although du Pont did not collect it, he most certainly would have appreciated its rich colors and exquisite design.

The Smoking Room (Fig. 9) at Chestertown House included one of the most unusual rugs in du Pont’s collection.40 Inspired by oak trees, the design is defined by acorns and oak leaves in a “pink” central medallion that reaches out from the center like the branches of a tree, followed by a green oval with oak leaves in the second ring.41 Holly leaves and red berries fill the border, while a freestyle “kaleidoscope ground” separates the border from the two central rings.42 The greens of the rug contrast dramatically with the blue China on the room’s shelves, while the rug’s reds are picked up by the bindings of many of the books, which du Pont may well have selected as much for their color as their content. A wing-back chair with decorative fabric is another bold creative choice for this room. Again, a rug in the Winterthur collection (Fig. 10) further illustrates du Pont’s aesthetic. Although lacking the greens and reds of the Smoking Room rug, this example, dating from between 1820 and 1860, explores shades of brown. Ferns dominate the design, while a sparsely decorated central medallion suggests a pool of water. The oak and fern rugs point to du Pont’s interest in nature-inspired designs beyond flowers.

An abstract rug in the Dining Room (Fig. 11) represents a shift away from du Pont’s general taste for floral designs.43 The muted shades of blue, pink, red, brown, and ivory in this rug also stand in contrast to the more intense florals in other rooms.44 As the catalog describes, “a background of warm tan . . . [features an] octagonal, log-cabin ornament with the corners separated by diamond-shaped forms in ivory, overlaid with four-petaled crosses in tones of pink and green.”45 It also asserts that the log cabin octagons are “copied in detail and form from those used in the Khiva Bokhara rugs,” an assertion that subtly undermines the originality of the rug’s maker.46 In this room, it is design, not color, that is the defining element. Curators Joshua Ruff and William Ayres describe the Dining Room as “a picture of simplified elegance, with light-colored paneling and cupboards filled with ceramics that then intrigued du Pont.”47 Although they neglect to mention the rug in their description, it most certainly adds to the simplified elegance that they describe.

Pictorial rugs also played an important role at Chestertown House, although du Pont reserved them for the bedrooms and such informal spaces as the bathhouse. The catalog not only provides ample evidence of pictorial rugs in the du Pont collection but also offers information on where they were displayed. One pictorial rug that depicts a farmer sitting outside his barn surrounded by an assortment of farm animals is described as “unique and naively interesting.”48 Significantly, this catalog entry acknowledges the creativity of the artisan: “Somehow, the one who made this rug seems to have caught the spirit of the dusk so vividly that the beholder can smell the dew-wet grass and hear the quiet murmur of the drowsy animals.”49 Rugs with less complex pictorial designs were also part of the du Pont rug collection, including some with images of family pets and smaller rugs that served as welcome mats. Two such pictorial rugs in the Winterthur collection are a welcome mat (Fig. 12) and a rug with two horses surrounded by multicolored abstract stripes and stylized flowers (Fig. 13). Du Pont was not at all averse to mixing pictorial rugs with floral designs. A bedroom on the first floor (Fig. 14) included a rug next to the bed depicting a horse about to drink at a water pump, while a floral rug can be seen at the foot of the bed. The catalog description also reflects an appreciation for the pictorial rug maker’s ability; the horse is “gracefully drawn,” and the composition is admired for the way the “red sunflower in full bloom in a red tub balances the pump.”50 Although located in the bedroom in the photograph, at another time the rug was placed in the men’s bathhouse.51

When du Pont inherited Winterthur, after his father’s death in 1926, he began to rethink his plans for Chestertown House. As museum director Leslie Greene Bowman summarizes, “Chestertown House had been a successful experiment, and du Pont was ready to repeat it on a grander scale.”52 As he began to shift his focus to Winterthur, objects from Chestertown House were transferred to Delaware, including some, but not all, of the hooked rugs. Some of the Southampton rugs were immediately put on display at Winterthur. For example, hooked rugs were placed in both the Pine Kitchen, now the Kershner Parlor (Fig. 15), and the Pine Hall, now the kitchen (Fig. 16). Jay Cantor observed, “Both these rooms, with their concentrations of rural furniture and strongly patterned hooked rugs, recall the interiors of Chestertown House.”53 Similarly, the Dancing Room, now Tappahannock Room (Fig. 17), at Winterthur was decorated with four hooked rugs, all from the Entrance Hall (Fig. 18) at Chestertown House.54 But the rugs that Cantor now connected with “rural furniture” were once viewed by du Pont as appropriate for any room at Chestertown House, including formal rooms, like the Living and Dining Rooms. By 1951, the year that Winterthur opened to the public, a museum publication revealed a codification of the hooked rugs as “folk art,” unfit for formal parts of the house. A brief chapter titled “Folk Art” explained, “At Winterthur there are impressive collections of this American folk art, arranged in rooms less formal than those with mahogany and satinwood, but rich in vigorous color and vital design.”55 While appreciated for their color and design, these rugs, nonetheless, were now viewed as appropriate only for the informal rooms in the new Winterthur Museum.

Although du Pont may have shifted his focus away from hooked rugs in decorating the formal rooms at Winterthur, the intrinsic value of his rug collection remained constant. Whether his rugs were on display or relegated to storage, he amassed an outstanding collection that holds historical significance, represents the stylistic diversity of the medium, and demonstrates outstanding craftsmanship. Their origins, often from rural communities, document a complex relationship between country artisans and cosmopolitan collectors like du Pont.56 The burgeoning market for hooked rugs that emerged in the 1920s was a welcome source of income for their makers, often living in the economically distressed areas. By the 1920s, manufactured rugs supplied much of the market, some made in working conditions no better than factories.57 While du Pont had the means to purchase only the best antique rugs, his collection was so large that some of his rugs in all likelihood came from this expanded market. The hooked rugs that remain in the Winterthur collection serve as a reminder of the labor required to make them, but even more, of the creativity of the individual rug makers.

Looking back, du Pont observed, “During the years that I have collected, I have had many satisfactions . . . in the contacts I have made with a great number of interesting people, in my greater consciousness of the development of our country, and in my immensely increased appreciation of the generations that have preceded us.”58 Cantor recognized that du Pont became “a prime mover in the reevaluating of American arts on an aesthetic basis.”59 Judging by the seriousness with which he used them to decorate Chestertown House, hooked rugs were a significant part of that reevaluation. His rug collection provides insight into the traditions that define American craft as it emerged in the nineteenth century and continued into the twentieth and establishes a meaningful creative link between the craft production of rural rug makers and du Pont himself as an influential tastemaker. He clearly valued that link, because, while fewer hooked rugs were on display at Winterthur than at Chestertown House, he left detailed instructions in his will concerning their display and care.60 Fundamentally, the hooked rug collection at Chestertown House and, to some extent, now at Winterthur reveals the outstanding potential of hooked rugs as a form of creative expression. The rugs aided du Pont in the development of his decorating aesthetic, and because he was such an avid and discerning connoisseur, an outstanding collection of American hooked rugs has been preserved to tell an even larger story about their significance.

Acknowledgments

About the Author

1 H. F. du Pont, foreword to American Furniture: Queen Anne and Chippendale Periods in the Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, by Joseph Downs (New York: MacMillan, 1952), v.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Jay E. Cantor, Winterthur, rev. ed. (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1997), 113.

6 Denise Magnani, The Winterthur Garden: Henry Francis du Pont’s Romance with the Land (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1995), 78–79. See also Denise Magnani, “The Winterthur Garden: A Romantic Modern Masterpiece,” Winterthur Magazine, Winter 2002, 14–19; and Karen Kegelman, “‘Color is the thing’: Enjoying H. F. du Pont’s Landscape Design, Inside and Out,” Winterthur Magazine, Winter 2003, 8–35.

7 Jeanne Marie Teutonico, “Marian Cruger Coffin: The Long Island Estates; A Study of the Early Work of a Pioneering Woman in American Landscape Architecture” (master’s thesis, Columbia University, 1983), 40.

8 It was after seeing Sleeper’s house in Gloucester that du Pont decided to build his “American house” in Southampton. Du Pont, foreword to American Furniture, v. Sleeper also assisted du Pont with Winterthur until they had a falling out because du Pont thought Sleeper was not putting in enough hours of work. But while working together into the late 1920s, the two men held a shared aesthetic vision. In a 1925 letter to Sleeper about lighting, du Pont describes his own taste as “conventional” when compared with the more eclectic taste of Sleeper: “I find your lights are so delightfully arranged—so cleverly placed with always some definite effect in mind—that it makes me quite desperate about my perfectly conventional arrangement of lights.” Du Pont to Sleeper, July 7, 1925, Henry Francis du Pont Papers, Winterthur Library, Winterthur, DE (hereafter cited as du Pont Papers). As late as 1928, the men still seemed to be working well together. Sleeper wrote to du Pont, “Confidently, it helps me immensely to feel that my client thinks I am doing the right thing and has confidence in my taste. I have so constantly to do things that I do not like much [for other clients] and would not do in my own house that I look forward with much excitement to helping you with your house.” Sleeper to du Pont, October 26, 1928, du Pont Papers.

9 Paul Hollister, Beauport at Gloucester: The Most Fascinating House in America (New York: Hastings House, 1951), 1.

10 Philip Hayden, “Henry Davis Sleeper: A Chronology,” in Beauport: The Sleeper-McCann House (Boston: Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, 1990), 103–4.

11 In this letter, Sleeper advised du Pont to make a “very attractive and interesting room” by placing a flat arch at the end of a barrel-vaulted ceilings. Sleeper declares, “No doubt the architect might resist this idea as not being perfectly regular, but unless you insist upon the seeming eccentricities, I think the room might look too Georgian and ordinary.” Sleeper notes in the same letter that du Pont shared this vision: “If the idea strikes your fancy, however, as you were kind enough to suggest the other day that it did, I know you will have tact and ingenuity enough to manage it.” Sleeper to du Pont, September 2, 1924, du Pont Papers.

12 Philip Hayden, “Beauport, Gloucester, Massachusetts,” Antiques, March 1986, 623.

13 Hollister, Beauport at Gloucester, 6.

14 Ibid.

15 Paul Hollister, “The Building of Beauport, 1907–1924,” American Art Journal 13, no. 1 (Winter 1981): 86.

16 Ibid.

17 Hollister, Beauport at Gloucester, 10.

18 Margaret Lathrop Law, “The Hooked Rugs of Nova Scotia: A Rapidly Developing Industry Indigenous to North America,” House Beautiful, July 1928, 58.

19 For a summary of this hooked rug market, as well as its connection to modern art, see Cynthia Fowler, Hooked Rugs: Encounters in American Modern Art, Craft and Design (Farnham, UK: Ashgate, 2013).

20 See Burnham’s advertisement reproduced in Jessie Turbayne, Hooked Rugs: History and the Continuing Tradition (West Chester, PA: Schiffer Publishing, 1991), 98.

21 R. W. Burnham to du Pont, December 1, 1928, du Pont Archives.

22 Henry Francis du Pont Antique Dealers Papers, Winterthur Library.

23 Antiques magazine published an advance listing of objects on auction in the May 1924 issue. A copy of the listing in the du Pont Papers is filled with notations on prices for rugs and other objects that du Pont was apparently interested in purchasing. For more on Nutting, see Thomas Andrew Denenberg, Wallace Nutting and the Invention of Old America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003).

24 Du Pont to Caswell Barrie, October 3, 1924, du Pont Papers. Barrie apparently found the rugs du Pont was looking for and had them delivered to Tiffany Studios where du Pont was to pick them up. Barrie to du Pont, November 25, 1925, du Pont Papers.

25 Ayer’s letters to du Pont were not completely out of the blue; he had a connection to du Pont through F. W. Pickard, one of du Pont’s vice presidents.

Ayer was founder and president of Eastern Manufacturing Company in Brewer, Maine. See Pauleena MacDougall, “The Life and Career of Bangor’s Frederick Wellington Ayer (1855–1936),” Maine History 45, no. 1 (December 2009): 49–52.

26 F. W. Ayer to du Pont, August 9, 1930, du Pont Archives.

27 Ibid.

28 Du Pont to F. W. Ayer, August 15, 1930, du Pont Papers. In this letter, du Pont writes that he was sending “the balance due” on the rugs, suggesting he had paid additional monies previously.

29 Du Pont to Stephen Van Rensselaer, August 11, 1925, du Pont Papers.

30 Memorandum from Stephen Van Rensselaer to du Pont, May 25, 1928, du Pont Papers. Louise Crowninshield also shopped at Van Rensselaer’s shop and is mentioned in correspondence between the two men.

31 Du Pont to Stephen Van Rensselaer, June 4, 1928, du Pont Papers.

32 Robert Hall to du Pont, September 12, 1930, du Pont Papers.

33 Du Pont to Robert Hall, September 19, 1930, du Pont Papers.

34 The catalog is quite extensive, so almost certainly not solely the work of du Pont, but there is no evidence of who put it together or wrote the notes.

35 “A Brief Description of the Old Hooked Rugs in Chestertown House, Southampton, Long Island,” [unpublished Winterthur Museum catalog], n.d., du Pont Papers. Each rug is catalogued with a number. The quote describes rug 1793.

36 Ibid.

37 Ibid., rug 1019.

38 The accession numbers are 1964.0796 and 1964.0797.

39 Mildred Cole Péladeau, Art Underfoot: The Story of Waldoboro Hooked Rugs (Lowell, MA: American Textile History Museum, 1999), 5. I am indebted to Millie for her willingness to share her research with me when I first began my own work on hooked rugs.

40 “A Brief Description of the Old Hooked Rugs,” rug 813. Although described as having a “conventionalized leaf, acorn and berry design” in the catalog, the rug design is quite unusual for a hooked rug.

41 From the photograph, the central medallion looks red, but it is described as pink in the catalog.

42 “A Brief Description of the Old Hooked Rugs.”

43 Ibid., rug 2657.

44 These are the colors identified in “A Brief Description of the Old Hooked Rugs.”

45 Ibid.

46 Ibid. Originating from Central Asia, Khiva Bokhara rugs were a popular type of Oriental rug.

47 Joshua Ruff and William Ayres, “H. F. du Pont’s Chestertown House, Southampton, New York,” Magazine Antiques, July 2001, 103.

48 “A Brief Description of the Old Hooked Rugs,” rug 8499. It is one of the only rugs in which no information is given on where it was displayed at Chestertown. Perhaps du Pont concluded that the rug was too precious to use.

49 Ibid.

50 Ibid., rug 6415.

51 Ibid.

52 Wendy Cooper, An American Vision: Henry Francis du Pont’s Winterthur Museum (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2002), 17.

53 Cantor, Winterthur, 119.

54 I have identified three of the four rugs as rugs 402, 403, and 404 in “A Brief Description of the Old Hooked Rugs.”

55 Joseph Downs and Alice Winchester, The Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, Winterthur, Delaware (New York: Magazine Antiques, 1951), 39.

56 Along the same lines, Rosemary Krill and Maria Shevzou make efforts to expand the story of Winterthur by including the voices of enslaved builders, tenants, the wealthy first owners, and subsequent owners of the Montmorenci House (in Warren County near Inez, North Carolina) in their consideration of the architectural elements of Montmorenci that ended up at Winterthur. See Rosemary Krill and Maria Shevzou, “The Transformation of Montmorenci,” Winterthur Portfolio 51, no. 4 (2017): 201–49.

57 See Eileen Boris, “Crafts Shop or Sweatshop? The Uses and Abuses of Craftsmanship in Twentieth-Century America,” Journal of Design History 2, nos. 2–3 (1989): 175–92.

58 Du Pont, foreword to American Furniture, vi.

59 Cantor, Winterthur, 32.

60 The Last Will and Testament of H. F. du Pont, first draft July 9, 1952, final draft February 29, 1964, du Pont Papers. Du Pont was quite specific about which rugs were to go to Winterthur from Southampton upon the death of Mrs. du Pont. He rejected only a few of the rugs from Chestertown House, noting, “A very few of these rugs due to their recent date might not be needed in the Museum.” In another example of his consideration of the rugs, in this instance in relation to color, he identified in his will the rugs to be moved to Winterthur from Mrs. du Pont’s bedroom and vestibule as the “hooked rugs with blue predominating.” He specifically noted that hooked rugs at Winterthur should be exhibited in the Commons Room, Red Lion Entrance Hall, Historical Blue China Room, Glass Room, fifth floor, Portsmouth Room, and fourth floor rooms. Unfortunately, many of the hooked rugs that du Pont might have wanted to preserve are no longer part of the Winterthur collection.