The Global Roots of an American Family Record Sampler

INTRODUCTION

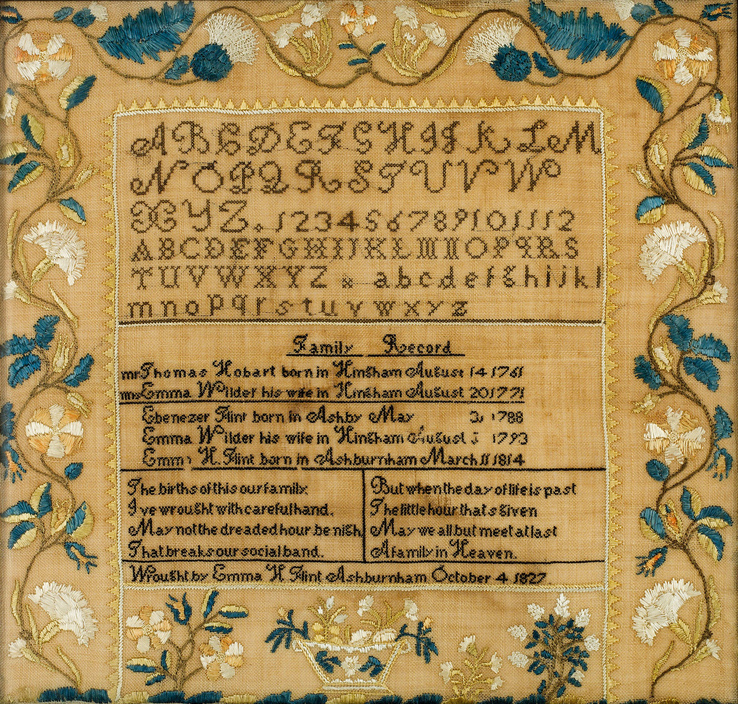

In 2020 the Metropolitan Museum of Art purchased a family record sampler at auction that is a model of beautiful stitchery and sophisticated design. However, following several years of intensive study, the Poyen family record sampler, completed in about 1819, has proved to be much more than a lovely object stitched by a young woman. It has revealed a remarkable and rarely told story of late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century French Caribbean immigration to the United States, and one family’s assimilation into the thriving towns along the Merrimack River in Massachusetts (fig. 1).

The first clue to this complex story lies in the names of the children listed on the Poyen family record sampler. Anglicized names such as “Mary Antoinette” and “Francis Louis” are clearly references to the queen and king of France who were deposed and executed in 1793 during the French Revolution. The key to these names is the heritage of Elizabeth Josephine Poyen (1806–1868), who was probably the sampler’s maker. Elizabeth was born in Rocks Village, a parish of Haverhill, Massachusetts, the eldest child of Joseph Rochemont de Poyen (1767–1850), whose name was anglicized to Joseph Poyen at some point after his arrival in the United States in 1792, and Sally Swett Elliot Poyen (1781–1858). Sally was the daughter of Thomas Elliot (1752–1818), a local tavern keeper, and Sally Swett Elliot (1761–1833), and both were descendants of English settlers who arrived in Essex County, Massachusetts, in the seventeenth century. Elizabeth’s father was the son of Pierre Robert de Poyen de Saint Sauveur (1740–1792), an aristocratic French sugarcane planter from Guadeloupe, West Indies, and his wife, Marie Joseph Mauvif (1743–1780).1 This seemingly simple piece of girlhood embroidery prompted us to examine the somewhat unexpected welcome and acceptance that a royalist French Catholic family found from the American citizens of Newburyport and Haverhill. It also made apparent the mutually beneficial connections between sugarcane planters from the French West Indies and the people of the shipbuilding towns on the Merrimack River. Both groups were significant contributors to the infamous triangle trade in enslaved people, sugar, and rum that operated between ports in New England, Africa, and the Caribbean.

In the eighteenth century, the British North American colonies were active participants in the transatlantic triangle trade. Ships built throughout New England, including Newburyport, carried New England rum to coastal East Africa, where it was exchanged for enslaved human beings. The ships then brought their human cargo, along with New England wood products and foodstuffs, to plantations in the American South as well as to sugar plantations in the West Indies. The codfish caught and salted in New England and the Maritime provinces of Canada was particularly important to the trade, since the West Indian islands did not produce enough food to feed their huge population of enslaved persons. In the West Indies, enslaved Africans and New England goods were exchanged for sugar and molasses. The molasses, upon arrival back in New England, was made into millions of gallons of rum, allowing the process to begin again. Connections made through this trade brought members of the de Poyen family to Massachusetts, where, twenty-seven years after their arrival, Joseph Poyen’s American-born daughter created a fashionable family record sampler.

FAMILY RECORD SAMPLERS

The Poyen sampler names Elizabeth’s parents, Joseph and Sally, their birth dates, and the date of their marriage, as well as the names and birth dates of the seven eldest Poyen children. There was no space left to list the births of two later siblings, in 1820 and 1825, after Elizabeth had finished the sampler. Because of this omission, we can place the probable date of the sampler’s completion to between 1819 and 1820, before the next child was born. It is logical to assume that the sampler was made by fifteen-year-old Elizabeth (b. 1806), who was the only Poyen daughter of the proper age to make a sampler of this quality, as well as the eldest daughter. Family record samplers were most often the product of either the eldest or the youngest daughter in the family.3

In its overall composition and details, the sampler displays design elements that relate to other samplers from Essex County, Massachusetts, but that perhaps also subtly reflect the maker’s French heritage. The horizonal format of the Poyen family record sampler is characteristic of other Essex County examples made in the first decades of the nineteenth century. So, too, is the wide, three-sided satin-stitched border featuring a meandering floral vine with large roses in full bloom and the hilly lawn at the bottom with an overflowing basket of flowers flanked by leafy trees (fig. 3).4 It has not yet been determined who taught Elizabeth to design and sew her sampler; she may have taken a needlework class with a private teacher, or she could have attended one of several known Haverhill schools for young ladies that were extant while she was growing up. The sampler’s design most resembles those made at Miss Parker’s School (c. 1801–c. 1827).5

THE DE POYEN FAMILY IN GUADELOUPE AND NEWBURYPORT

Elizabeth’s father, Joseph Poyen, was a descendant of Jean de Poyen (1650–1706), who emigrated from France in the mid-seventeenth century to Guadeloupe in the French West Indies, during France’s early colonization of the island group.7 While the original attempts at colonization were undertaken by chartered French trading companies, such as the French West India Company, in 1674 the islands were passed to the authority of the French crown. Large parcels of land were both bought by and bestowed to people willing to farm the land to benefit the French economy, as well as to gain personal wealth. The major crop propagated in Guadeloupe was sugarcane, and as early as 1644, enslaved Africans were brought there to work on the plantations.

Joseph Poyen grew up on his family’s sugarcane plantation “Habitation Piton” near Sainte-Rose on the coast of Basse-Terre, the westernmost island in the group of three that constitute Guadeloupe. In the late nineteenth century, a family descendant described the plantation as follows:

The arrival of a group of aristocratic French royalists fleeing Guadeloupe was a notable event, though these were not the first French émigrés who had sought refuge in Newburyport.15 People in the port city of about five thousand largely Anglo-Americans may have retained an appreciation for France due to its military support during the American Revolution. Thus, during the French Revolution, many Americans felt that France and the United States were bound together in a single, anti-monarchy cause. But when, in the 1780s and 1790s, US coastal cities saw an influx of French émigrés loyal to the king fleeing from both continental France and the French Caribbean islands, was there debate about how they should be welcomed? It is hard to know in all cases, but within a few years, the de Poyens became an integral part of the local community. Although Joseph de Poyen arrived in America from a family plantation dependent on chattel slavery, surely an anathema to some New Englanders, the family’s local connections to the triangle trade likely eased their way. Additionally, the de Poyens’ status as aristocratic French émigrés, as well as their presumably comfortable financial status, must have contributed to their assimilation. Moreover, at this time, many of the new American gentry who had become wealthy through trade sought to emulate French culture, manners, and fashion.16

Much of what we have been able to learn about the de Poyen family in the United States comes from Newburyport’s prolific late nineteenth-century chronicler, Sarah Anna Emery (1821–1907), as recorded in her book, Reminiscences of a Nonagenarian (1879), in which she recounts the remembrances of her ninety-two-year-old mother, Sarah Smith Emery (1787–1879). Emery devoted a complete chapter to the various French families who made their home in Newburyport following the French Revolution.17 Almost one hundred years after the de Poyen family’s arrival in Newburyport, she described the events surrounding it in highly dramatic terms:

As chronicled by Emery, Elizabeth’s grandfather Pierre Robert de Poyen de Saint Sauveur “inherited all the instincts and pride of the aristocracy of France” and was “a staunch royalist and an ardent defender of King Louis XVI.” Pierre Robert’s time in America, however, was short-lived. He died seven months following his arrival in Newburyport on October 14, 1792. Emery surmises that “the loss of home, change of climate, grief and anxiety, was too much for the exile.”19 At the time of Pierre Robert’s death, there was no consecrated burial ground for Catholics, and the senior de Poyen was laid to rest in the local Protestant cemetery in a “quiet spot . . . apart from others.”20 Three months later, Louis XVI was executed on January 21, 1793. Of major concern to plantation owners such as the de Poyens, slavery in Guadeloupe was banned for eight years, from 1794 until 1802, when Napoleon I’s government reestablished slavery in the French colonies.21 After the family left the island in 1792, their plantation was seized by the interim government, which handed over its management to a trustee. When slavery was reestablished in 1802, Joseph Poyen did not return to Guadeloupe to retake possession of his father’s plantation, and it was auctioned off to another owner in 1803.22

Following the patriarch Pierre Robert’s death, his twenty-five-year-old son, Joseph, eventually the father to the sampler maker, made his home in Newburyport. Emery records that Joseph’s early years were spent “in careless, easy living, dividing his time between the town and the romantic villages along the river’s bank.”23 One can speculate that this young émigré aristocrat soon learned to speak English, in an effort to get to know the community, and perhaps looked for a way to make a living.

By the fall of 1797, five years into his stay, Joseph Poyen (having dropped the aristocratic “de” from his name), astutely perceived the social environment of Newburyport’s gentry and their interest in French styles and customs. Using an adaptation of his name, “Poyen Rochmond,” he advertised in local newspapers the opening of an evening dancing school “for the young Ladies and Gentlemen” of Newburyport (fig. 8). Local advertisements record that fellow Frenchmen Renard & Barbot had a competing dance class and that Mr. Renard also offered French-language classes on Mondays and Thursdays—in the morning for ladies and in the evening for gentlemen. The following year, Joseph advertised his skills as a swordsman under the headline “Useful Art,” offering to teach the “young Gentlemen of this town . . . the useful and necessary art of self-defense by the Broad Sword.”24

In some of his “Dancing School” and “Useful Art” advertisements, Joseph invited students to apply at his lodgings on Liberty Street in Newburyport, but in 1798 “Poyn Joseph” was listed as one of the householders in the neighboring city of Haverhill, with his home valued at $650.25 Period documents record that this house at 38 East Main Street was located in “Rocks Village” in eastern Haverhill, in the same neighborhood as three local families with deep roots in the community: the Elliots, the Ingalls, and the Whittiers. Members of each of these families would marry into Joseph Poyen’s family.

On March 5, 1805, when he was thirty-six, Joseph married Sally Elliot, the twenty-four-year-old daughter of Thomas Elliot.26 Elliot’s ancestors were members of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and became Haverhill landowners beginning in the early 1700s.27 Joseph’s cousin the Count de Vipart wooed Mary Balch Ingalls (1786–1807) with “moonlight sails” and violin serenades, according to Emery, and he and Mary were married only a few days after Joseph and Sally on March 21, 1805.28 Mary Ingalls’s wedding “created a great sensation” and she assumed the title of Countess de Vipart, but she died of consumption less than two years after her marriage. Later in the nineteenth century, Mary Ingalls de Vipart became a legendary figure as the heroine of John Greenleaf Whittier’s 1864 poem “The Countess.”29 After Mary’s death, François left Massachusetts and returned to Sainte-Rose, Guadeloupe, where a year later he remarried. He died there on September 15, 1811, at age thirty-five.30

Although Thomas and Sally Elliot apparently did not like their daughter “marrying a foreigner,” Joseph and Sally Poyen’s marriage lasted until Joseph’s death in 1850.31 During that time, the Poyens raised nine children, six daughters and three sons. A pastel portrait of Sally, likely done at the time of her marriage, shows her with fine features, dark eyes, and black hair, wearing a simple neoclassical white dress with a ruffled collar, perhaps her wedding dress (fig. 9). Emery described Sally as “a handsome, brilliant girl” who “made Rochemont de Poyen a most excellent wife,” and she characterized Joseph as “a genial Frenchman; a lithe active man. . . . Though irascible and impatient, he was the soul of wit and good humor, happy in making all around him happy.”32

As seen in the Poyen family sampler, Joseph and Sally chose their children’s names to reflect both their fraternal and maternal family heritages. Mary Antoinette and Francis Louis are anglicized names that attest to Joseph’s continuing loyalty to the deposed French monarchy. From the maternal Elliot and Swett families, with their deep English roots in the Haverhill area, there is Sally’s namesake, Sally Elliot, and a second son, Thomas Elliot. Other children, John Saint Sauveur and Abigail Rochemont Weld, have names that meld the lineage of both parents. The tradition of naming offspring after family ancestors would continue for several generations of the extended Poyen family.

During the years when his children were growing up, property deeds record that Joseph Poyen owned land in various locations in Rocks Village.33 In these deeds, he is variously described as a tobacconist, a comb maker, and a trader. Emery wrote that Joseph was “a great fancier of horse flesh, always ready for a trade.” In his will, Joseph is listed as a “yeoman,” indicating that he was a small landowning farmer. As Emery remembered: “Years passed and grandchildren also came, and grew up to love the dear old man, whose delight it was to play and dance with them; he grew old in years but not in elasticity of spirit, and his life went out in glorious fullness, at a ripe old age [of eighty-three].”34 There is no evidence that while in Massachusetts Joseph was directly involved in the triangle trade, but his will and probate record valued his estate at $4,264.15 including $2,710.45 from Guadeloupe, an indication of some continuing connection to the family’s sugarcane fortunes.35 In today’s money, the total value of his estate was $165,119.77, with the portion from Guadeloupe equivalent to $104,886.08, the majority of the total.

THE NEXT GENERATION

Joseph’s success in the United States was carried on through his daughter Elizabeth’s line. On November 30, 1826, when she was twenty-one, sampler maker Elizabeth Poyen married Stephen Patten (1805–1869), a seventh-generation member of the Massachusetts Patten family.36 Following their marriage, the couple moved to Stephen’s hometown, neighboring Amesbury, where he established a grocery and carriage supply store.37 Stephen brought Elizabeth’s younger brother, John Saint Sauveur Poyen (1818–1880), into his business and in 1838 made him a partner in Patten & Poyen & Co. Included in Joseph Poyen’s 1850 inventory after his death are notes to Patten & Poyen indicating that he made loans to the business. In 1848 John Saint Sauveur purchased a controlling interest in the business from his brother-in-law, and the firm became known as John S. Poyen & Co.38 By the 1870s, John Saint Sauveur Poyen, the son of immigrant Joseph, was the largest taxpayer in Merrimac, another nearby town, amassing a “fortune” and becoming “one of the most prominent” citizens of area.39 He married Elizabeth B. Kennison on November 18, 1843, and they had six children who carried traditional family names. Proving that the family ties remained closely knit between the American Poyens and those in Guadeloupe, in January 1880, John Saint Sauveur visited his father’s relatives still living on the island. While there he contracted yellow fever and died on February 22, 1880.

Elizabeth and John Patten had five children. Their two youngest children were born in Portland, Maine.40 Presumably the family took Elizabeth’s sampler with them when they moved into their new home there. Elizabeth Poyen Patten died on April 6, 1868, at age sixty-four, and her husband the following year on October 24, 1869. They are both buried in the Evergreen Cemetery in Portland in a large Hamlen family plot.41

KEEPING THE DE POYEN NAME ALIVE

In April 1849, Elizabeth’s eldest daughter, Anne Crosby Patten (1828–1911), married James Hopkinson Hamlen (1825–1903) in Portland. Hamlen was the owner of a large and lucrative cooperage and hardwood lumber company, J. H. Hamlen & Co. Anne and James’s children, grandchildren of Elizabeth Poyen Patten, perpetuated their familial association with the aristocratic French de Poyens. James Clarence Hamlen (1852–1936) and Maria Patten Hamlen (1855–1950) were active supporters of the New England Historic Genealogical Society. Together they donated a tablet in the stair hall of the society’s Boston building in honor of their great-grandfather. The tablet shows an image of the de Poyen family coat-of-arms with the following inscription: “In Memory of Joseph Rochemont de Poyen de St. Sauveur, Nephew of the Chevalier de St. Sauveur, Grand-Nephew of the Countess des Saillons-d’Estaire, Newburyport Massachusetts, 1792. Erected by James Clarence Hamlen and Maria Patten Hamlen.”42

James Clarence Hamlen carried on the J. H. Hamlen and Son, Inc. family business, developing a second location for its headquarters in Little Rock, Arkansas. In 1954 he established the small town of Poyen, Arkansas, in honor of Joseph Poyen. James Clarence Hamlen’s son (and Joseph Poyen’s great-great-grandson), James Hopkinson Hamlen II (1913–2004), took over the business in Little Rock until 1988, when he sold it to the Weyerhaeuser Company. Soon after, James established the James H. Hamlen Charitable Remainder Trust from which he made philanthropic gifts exceeding twenty million dollars throughout his lifetime.43

It is our conjecture that Elizabeth’s sampler was passed down through members of the Hamlen family in Portland, Maine. In 2001 Amy Finkel, of M. Finkel & Daughter, a noted Philadelphia dealer of American samplers, purchased it from Paul Buxton (1942–2017), a Portland auctioneer and antiques appraiser. Finkel sold the sampler to the collector Dr. Gail Furman (1946–2019). After Dr. Furman’s death, her folk art collection was sold at auction at Doyle’s New York on January 23, 2020. The sampler, lot 296, was purchased by the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Traditionally, samplers have been studied as a means to research the family history of the girl who made it. This genealogical approach usually yields information about the family, often emphasizing deep American roots. Indeed, the first important book on the subject, Ethel Stanwood Bolton and Eva Johnston Coe’s American Samplers (1921) was published by the Massachusetts Society of the Colonial Dames of America. This book remains a marvelous resource, but it was written at the height of the Colonial Revival, and its stated purpose was to preserve “the memory of our ancestors” through studying their needlework. The Colonial Revival was a reaction, at least in part, to the millions of European immigrants flooding into the United States in the early twentieth century, whose politics and beliefs were thought to threaten the core values of the Anglo-American community. The Poyens’ story, also found through researching a sampler, tells of a quite different welcome found by a foreign immigrant about one hundred years earlier.

In recent years, the study of samplers has broadened to include more than simple genealogy. Elizabeth Poyen’s family record is a perfect example of how a sampler can reveal social history, patterns of immigration, French and American relations in the early nineteenth century, and in particular the acceptance by New Englanders of their French partners in the triangle trade due to their mutual economic interests. While we consider this sampler to be a rare example that tells such a multifaceted story, it inspires us to more thoroughly research other samplers in the museum’s collection, in the hope of finding important histories they too may bring to light.

Acknowledgments

About the Authors

Amelia Peck graduated from Brown University and received an MS in Historic Preservation from Columbia University. Her areas of expertise include American textiles and period rooms. In her forty years at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, she has curated numerous exhibitions, and has also been the author, contributing author, or general editor of many publications, including American Quilts and Coverlets in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1990), Candace Wheeler (2001), Interwoven Globe: The Worldwide Textile Trade, 1500–1800 (2013), and History Refused to Die: Highlights from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation Gift (2018).

Cynthia V. A. Schaffner is a decorative arts historian. Among her books and articles, she is co-author of American Painted Furniture (1997), and co-author of “The Founding and Design of William Merritt Chase’s Shinnecock Hills Summer School of Art and the Art Village” (Winterthur Portfolio, 2010). Since 1999 she has been a researcher at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, contributing to such catalogues as Art and the Empire City (2001), American Quilts and Coverlets in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (2007 edition), and Interwoven Globe (2013). She is presently researching and writing online entries for the Met’s American sampler collection.

1 For biographical details on the birth and death years of the de Poyen family members, see Massachusetts, Death Records, 1841–1915, Ancestry.com. See also “De Poyen,” Rocks Village in Haverhill, Massachusetts, accessed April 5, 2024, rocksvillage.org.

2 For a discussion of American family record samplers, see Gloria Seaman Allen, Family Record: Genealogical Watercolors and Needlework (Washington, DC: DAR Museum, 1989).

3 Allen, 4.

4 For a discussion of the samplers of Haverhill, Massachusetts, see Betty Ring, Girlhood Embroidery: American Samplers & Pictorial Needlework, 1650–1850 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1993), 1:124–29.

5 Ring, 127, fig. 143.

6 See objects 26.238.6a,b, 26.238.9a–f, and 26.238.17 in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

7 Biographical details for Joseph de Poyen are drawn from “Joseph Rochemont de ‘Saint Sauveur’ Poyen,” Church Street Cemetery, Merrimac, Essex County, Massachusetts; memorial no. 140290258, findagrave.com.

8 Sarah Anna Emery, Reminiscences of a Nonagenarian (Newburyport, MA: William H. Huse & Co. Printers, 42 State Street, 1879), 184. This description was provided to Emery by a Poyen descendant, James Hopkinson Hamlen (1825–1903), Elizabeth Poyen’s son-in-law. His help with the Poyen family history is mentioned in the preface to the book.

9 William S. Cormack, Patriots, Royalists, and Terrorists in the West Indies: The French Revolution in Martinique and Guadeloupe, 1789–1802 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2019), 13.

10 Conseil General de la Guadeloupe (cited hereafter as Conseil General), Poyen, Circuits et Interpretation (Petit-Canal) (2007), 10, cg971.fr. The de Poyens took ownership of this particular property in 1770, but according to Jean-Pierre Sainton, “The Poyen line, one of the most powerful families in the colony, possessed plantations at Capesterre [de Marie-Galante], Sainte Rose, Sainte Anne, Saint Louis de Marie-Galante, and Petit Canal”; Histoire et civilisation de la Caraïbe: Guadeloupe, Martinique, petites Antilles, vol. 2, Le temps des matrices: Économie et cadres sociaux du long XVIIIe siècle (Paris: Editions Karthala, 2012), 304. These five plantations were spread among the three islands (Basse-Terre, Grand-Terre, and Marie-Galante) of Guadeloupe, but our research did not include finding the dates and sizes of each of the extended de Poyen family properties. The authors would like to thank Sophia Kamps, Tiffany & Co. Intern (2022–23) in the Department of American Decorative Arts at the Met for her help as both a research assistant and translator.

11 This breakdown of seven people in the de Poyen family is published in Emery, but other sources seem to indicate that a group of nineteen people, including the de Poyen family’s bookkeeper, accompanied them on the journey. Conseil General, Poyen, 9.

12 Duane Hamilton Hurd, ed., “John S. Poyen,” in History of Essex County, Massachusetts, with Biographical Sketches (Philadelphia: J. W. Lewis, 1888), 2:1556.

13 Susan M. Harvey, “Slavery in Massachusetts: A Descendant of Early Settlers Investigates the Connections in Newbury, Massachusetts” (master’s thesis, Fitchburg State University, 2011), 12, 104. For this information, Harvey cited James A. Rawley and Stephen D. Behrendt, The Transatlantic Slave Trade: A History, rev. ed. (New York: W. W. Norton, 2005).

14 “Newburyport Rum Withstands the Test of Time—Almost,” New England Historical Society, accessed April 25, 2023, newenglandhistoricalsociety.com.

15 A group of ten people (three of them enslaved) are recorded as arriving in Newburyport from Guadeloupe on July 16, 1789. The same source recounts: “During the next two or three years the number of French refugees who came to Newburyport was unusually large. When peace was restored some of them returned to the West Indies, but others, worn down with grief and anxiety[,] died and were buried in the Old Hill burying-ground.” John J[ames] Currier, History of Newburyport, Mass; 1764–1905 (Newburyport, MA: printed by the author, 1906), 1:114.

16 For the assimilation of French immigrants from the West Indies and France in Philadelphia in the 1780s and 1790s, see François Furstenberg, When the United States Spoke French: Five Refugees Who Shaped a Nation (New York: Penguin, 2014), 137–226.

17 Emery, Reminiscences, chap. 36.

18 Emery, 183–84.

19 Emery, 184.

20 While the Poyen family were practicing Catholics for many years, as evidenced by Joseph and Sally Poyen having several of their children baptized in the Catholic church, at the time of Joseph’s death, among his assets was a pew in Haverhill’s Second Baptist Church. Thus, part of his assimilation included becoming a Protestant at some point. Boston Archdiocese, Boston, Massachusetts, Sacramental Records, vol. 48423, p. 8.

21 Slavery was not abolished in Guadeloupe until 1848.

22 Conseil General, Poyen, 9.

23 Emery, Reminiscences, 185. Several family members returned to Guadeloupe after peace was restored, and there were monies that came from Guadeloupe recorded in Joseph’s inventory at his death. Joseph always seems to have had money to live on and with which to purchase property, although there is no concrete evidence that he was ever involved in a lucrative career.

24 “Dancing School, Poyen Rochmond,” Impartial Herald (Newburyport, MA), September 19, 26, and 30, 1797; Newburyport Herald and Country Gazette, November. 20, 1798; “Messrs. Renard & Barbot,” Newburyport Herald and Country Gazette, November 20, 1798; “Useful Art. / Poyen Rochmond,” Newburyport Herald and Country Gazette, November 20, 1798.

25 George Wingate Chase, History of Haverhill, Massachusetts from Its First Settlement, in 1640, to the Year 1860 (Haverhill, MA: printed by the author, 1861), 469.

26 Massachusetts, U.S. Town and Vital Records, 1620–1988, s.v. “Joseph Poyen” (married March 5, 1805), and s.v. “Sally Elliot” (married March 5, 1805), Ancestry.com.

27 “Elliott Family,” Rocks Village in Haverhill, Massachusetts, accessed April 5, 2024, rocksvillage.org.

28 Emery, Reminiscences, 185; Massachusetts, U.S. Town and Vital Records, 1620–1988, s.v. “Mary Balch Ingalls” (married March 21, 1805), Ancestry.com.

29 Emery, Reminiscences, 185; John Greenleaf Whittier, “The Countess,” in Rebecca Ingersoll Davis, Gleanings from Merrimack Valley (Portland, ME: Hoyt, Fogg & Donham, 1881), 35–46.

30 Massachusetts, U.S. Town and Vital Records, 1620–1988, s.v. “François Félix Hector de Vipart Morainvilliers” (d. September 15, 1811, in Sainte-Anne Guadeloupe), Ancestry.com.

31 Hurd, History of Essex County, 1556.

32 Emery, Reminiscences, 185.

33 For a list of properties, see “De Poyen,” Rocks Village in Haverhill, Massachusetts, accessed April 5, 2024, rocksvillage.org.

34 Emery, Reminiscences, 185.

35 Inventory and Appraisement of the Estate of Joseph Poyen, Amesbury, Massachusetts, s.v. “Joseph Poyen” (1767–1850), Massachusetts, Wills and Probate Records, 1635–1991, Ancestry.com.

36 “Amesbury Marriages,” Massachusetts, U.S. Town and Vital Records, 1620–1988, s.v “Elizabeth Poyen” (married November 30, 1826), Ancestry.com; Thomas W. Baldwin, Patten Genealogy: William Patten of Cambridge, 1635, and His Descendants (Boston: printed by the author, 1908), 202–3.

37 Hurd, History of Essex County, 1556.

38 Hurd, 1556.

39 The Villager (Amesbury, MA), July 11, 1878; The Villager (Amesbury, MA), February 26, 1880.

40 For biographical information on the Patten children, see North America, Family Histories, 1500–2000, Ancestry.com.

41 The authors thank Michael Ciamaga, director of cemeteries and project management, Parks, Recreation and Facilities Management, Portland, Maine, for assistance in locating the Hamlen Cemetery plot in section H, lots 19–23.

42 “Memoirs,” New England Historical and Genealogical Record 105 (1951): 62–63. Even in the 1950s, family members were trying to reinforce their ties to French nobility. The Chevalier de Saint Sauveur was First Chamberlain to Count d’Artois, brother of the king of France, and a member of the French Navy (during the American Revolution, the French sent ships to the United States in 1778 to help support the Americans’ fight against the British). The chevalier lost his life during an anti-Catholic riot in Boston in 1778.

43 “$8 Million Gift Divided between Arkansas Children’s Hospital and UAMS,” press release, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, December 23, 2004, news.uams.edu.