Fancy Fraktur: Brocade Paper in Pennsylvania German Folk Art

Vivid watercolor images of flowers, birds, hearts, and suns have long visually defined fraktur, the illuminated folk art tradition popular among German Americans between the mid-eighteenth and mid-nineteenth centuries, pointing to the delight that German-speaking artists took in exploring the potential for the medium of watercolor to create vibrant, non-naturalistic imagery. During the twentieth century, scholars and curators—notably, those who were not fraktur specialists—frequently viewed these unabashed celebrations of materiality as quaint, naïve, or primitive markers of the untrained and provincial backgrounds of German-speaking scriveners.1 Yet, for the scholars who specialized in fraktur, knowledge of materiality and tools became essential for understanding this folk art, a focus that has long remained at the center of fraktur studies. From Henry Chapman Mercer’s 1897 examination of an early nineteenth-century artist’s paint box to more recent research into the origins of fraktur paper and pigments, the materials employed by fraktur artists have long deepened our appreciation of fraktur’s origins and its role in the lives of German speakers in North America.2

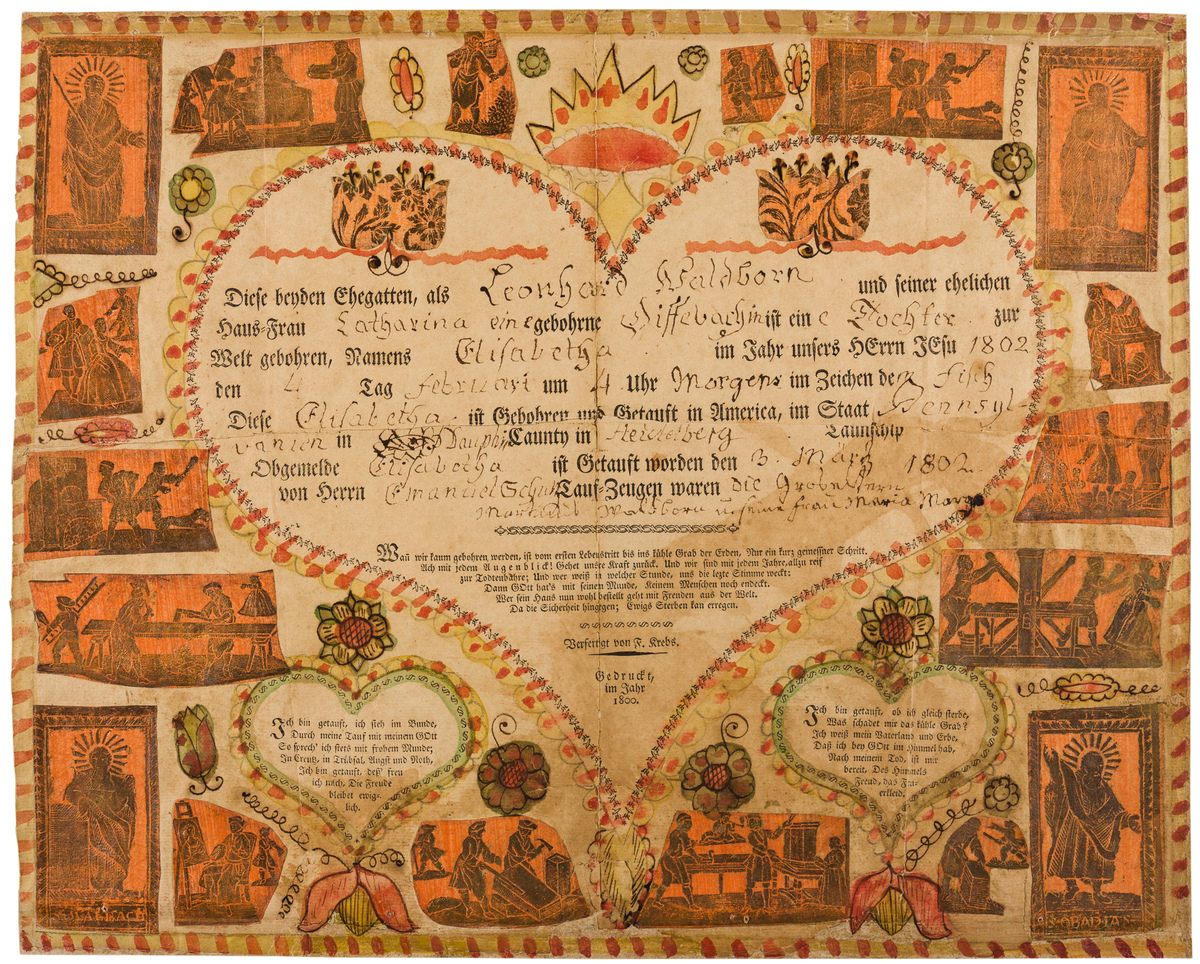

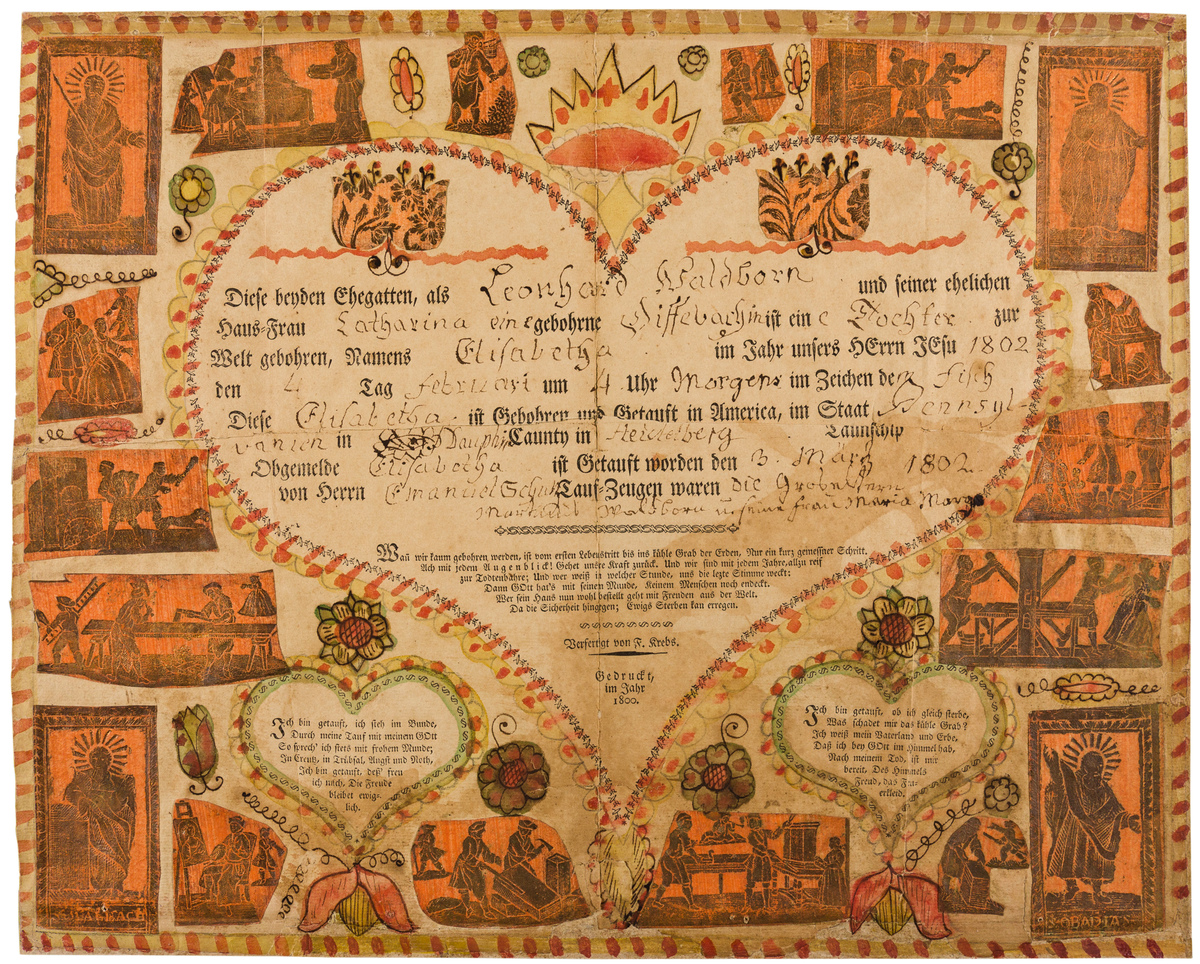

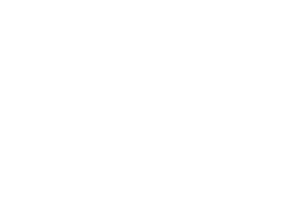

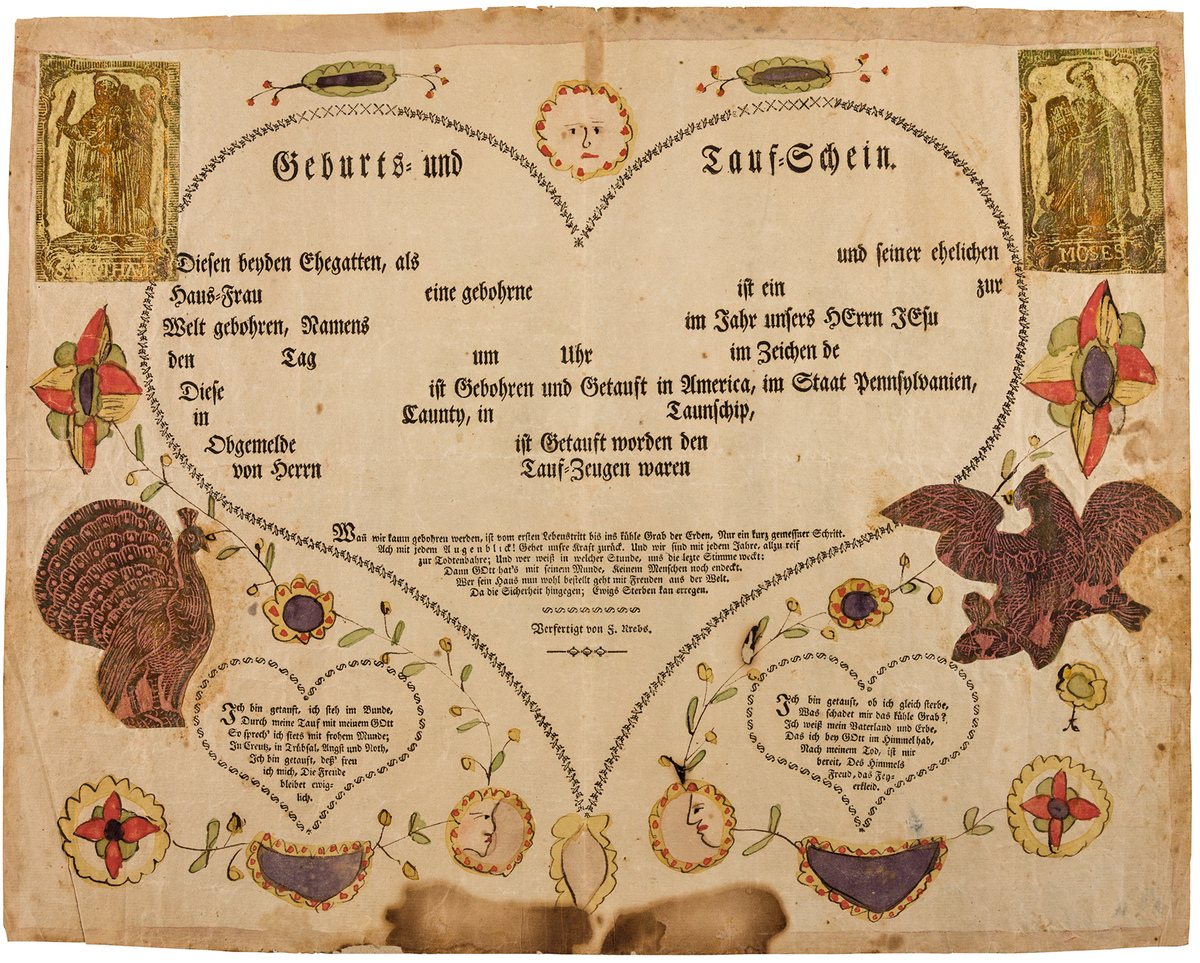

However, fraktur’s more opulent materials have escaped scholarly attention almost entirely. When exploring significant public and private collections of fraktur, one soon encounters birth and baptismal certificates—the most common type of fraktur—embellished with a veritable deluge of metallic foils in the shapes of animals, birds, flowers, saints, and period figures (fig. 1). Upon closer inspection, one observes that these foils, originally golden in color though now oxidized black, are embossed and pasted onto the surface of each illuminated certificate. These remarkable examples of “decoupage” fraktur reveal the ingenuity of their creators in transforming each certificate into a sculptural, three-dimensional object that would originally have shimmered in candlelight.3

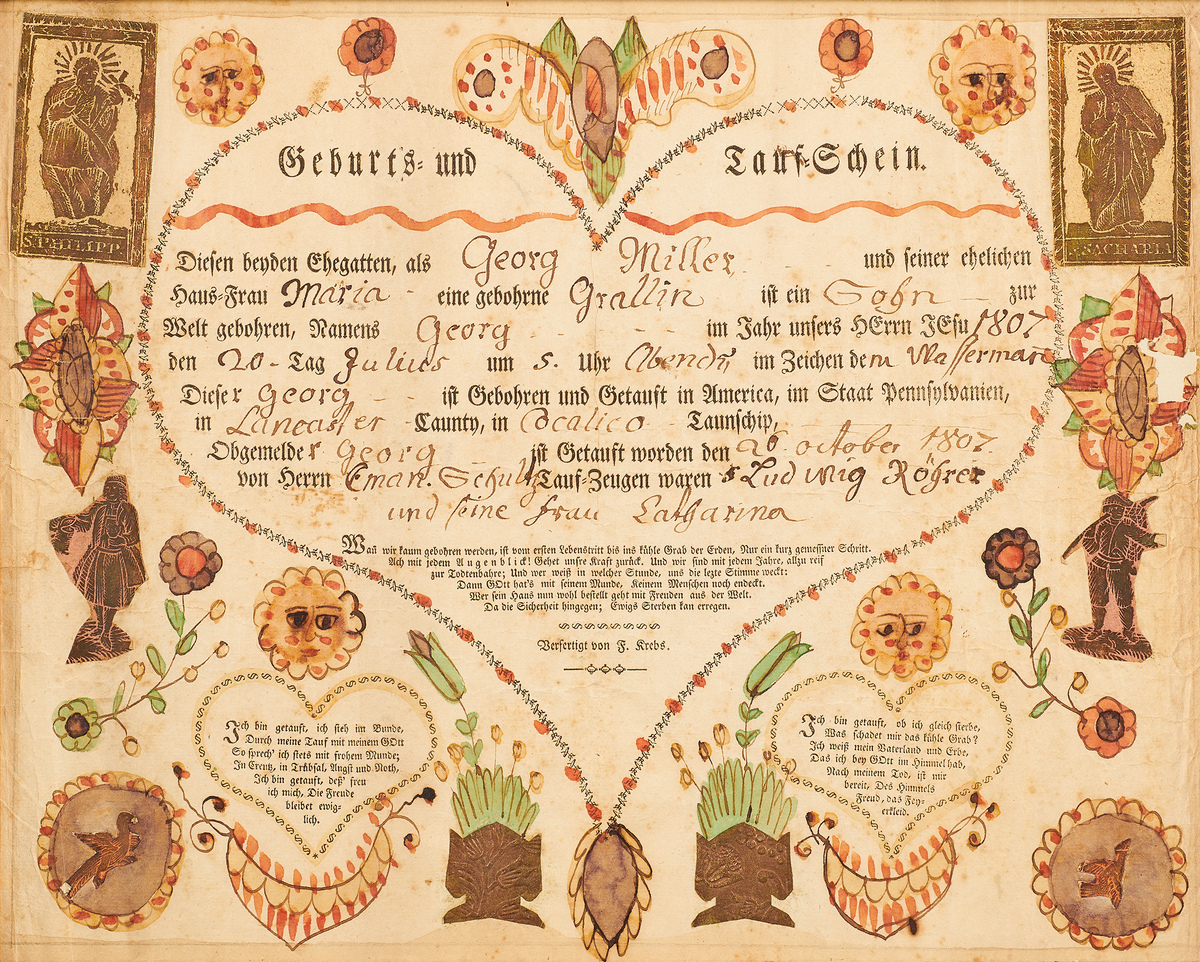

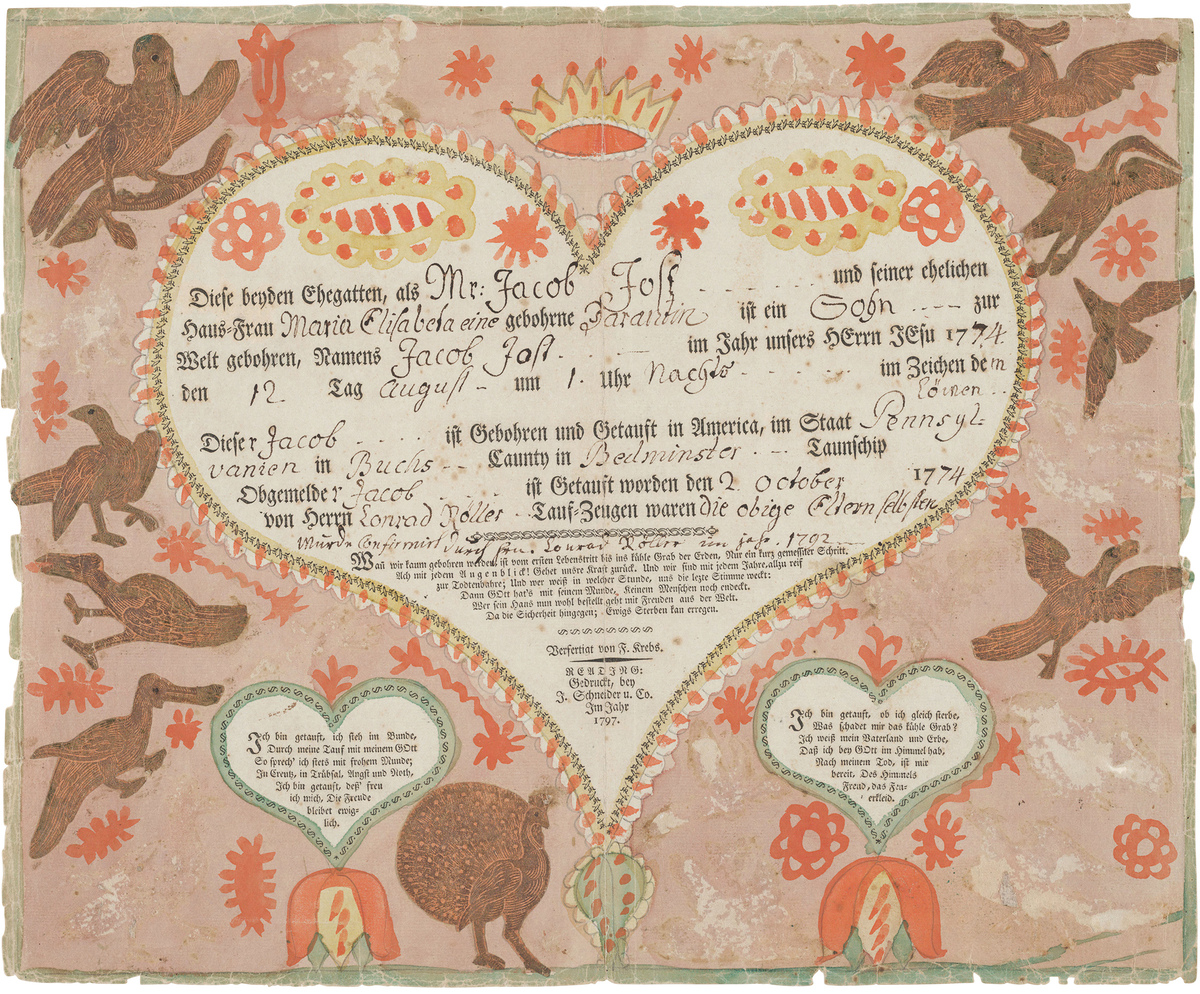

Developed at the turn of the nineteenth century, this inventive, visually impressive fraktur style offers a framework for broadening scholarly conceptions of fraktur from a primarily regional tradition to one with national, even global connections. The artist who developed this decoupage technique, the German-speaking schoolmaster Friedrich Krebs (1749–1815), is recognized as the most prolific of all fraktur artists.4 His significance extends beyond the size of his corpus, as he was a fundamental figure in fraktur’s transition from a primarily manuscript art to one that increasingly relied on printers (fig. 2). During this transitional period in the 1790s, Krebs also began to experiment with pasting embossed-and-gilt “brocade papers,” imported from Bavaria, onto his newly designed certificates. To scholars today, these decoupaged certificates offer a lens into fraktur’s connections with a global trade in German decorative paper. To period viewers, they highlighted a new interplay between print, manuscript text, and watercolor illumination, linking fraktur with contemporary Anglo-American fashions for “Fancy,” a cultural phenomenon that favored creative, emotive surface decoration. This essay considers both perspectives on these objects, framing Krebs as an astute entrepreneur who exploited transatlantic trade as well as AngloAmerican cultural trends when making and selling his wares.

Johann Jacob Friedrich Krebs was born to a family of shepherds around April 3, 1749, in Zierenberg in the Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel, a state of the Holy Roman Empire bordering the Rhine.5 Little is known of Krebs’s early life in Europe, but he reappears in the historical record as a British-allied Hessian auxiliary during the American Revolution, likely serving with the von Linsingen battalion grenadiers between 1776 and 1782.6 A definitive history of Krebs’s military service is complicated by the presence of numerous individuals recorded as “Johann Jakob Friedrich Krebs” in Hessian military rosters and the frequent misspelling of his name as “Kreps” throughout his career.7 Krebs may have briefly returned to Europe after the Revolution, but even this conclusion is challenged by spurious recordkeeping due to frequent Hessian desertions after the war. The first reference to Krebs’s civilian life in the United States appeared in 1787 with the birth of his son Georg Friedrich Krebs. Census records more consistently documented Krebs’s life throughout the 1790s and early 1800s, indicating his profession as a schoolmaster in Hummelstown, near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.8 Krebs passed away in 1815 at the age of sixty-six.

Figure 3 Friedrich Krebs, birth and baptismal certificate of Jacob Steininger, Northampton County, Pennsylvania, c. 1787. Ink and watercolor on paper, 12 1⁄2 × 15 in. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of Victor and Joan Johnson, 2009-40-8

This certificate was printed at the Ephrata Cloister for a different fraktur artist, Henrich Otto.

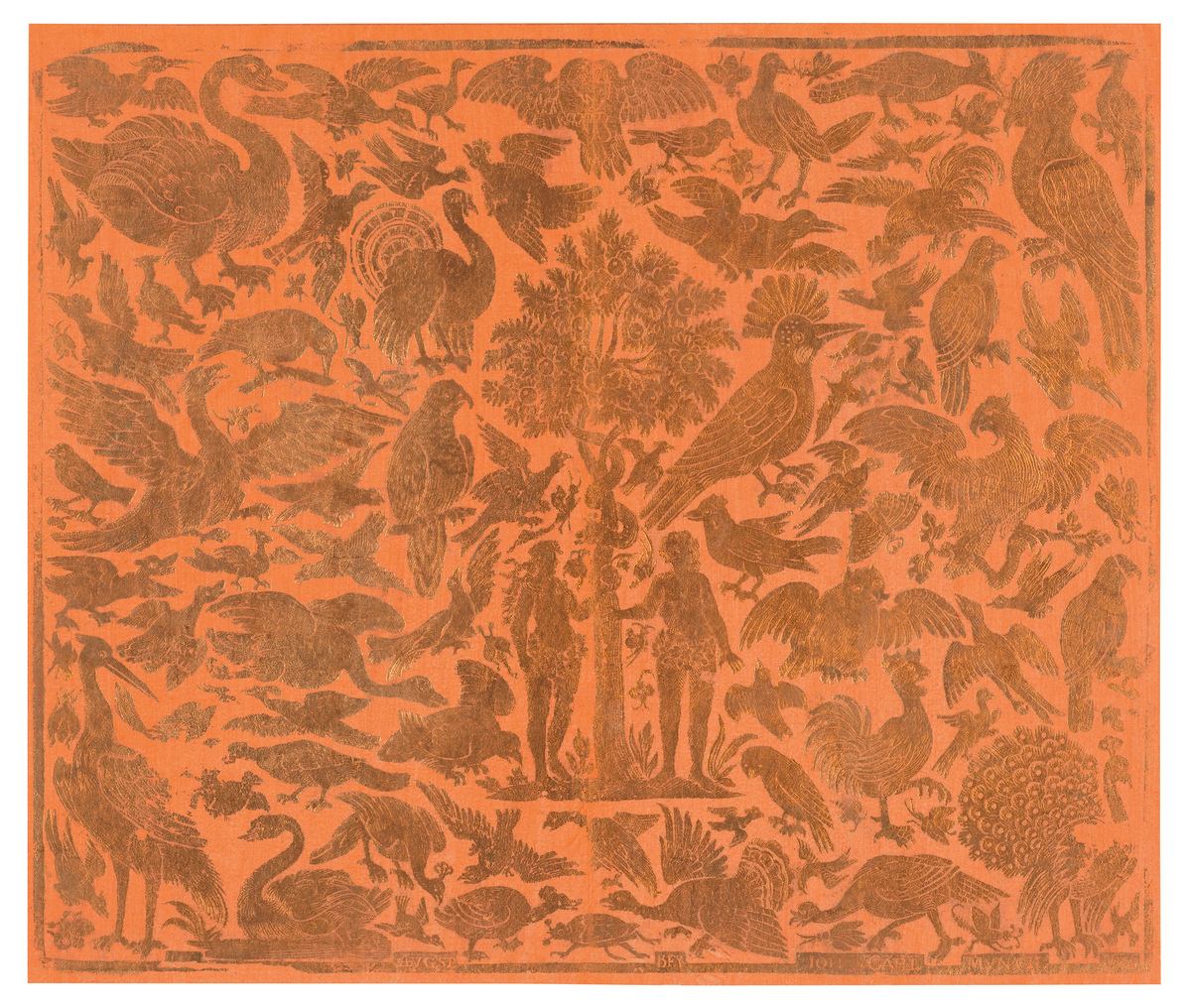

Figure 6 Printed sheet with pattern of leaves and fruits, likely Augsburg or Nuremberg, c. 1760–1800. Embossed and gilt foil on colored paper, 9 5⁄8 × 14 9⁄16 in. Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum, RP-D-2018-103

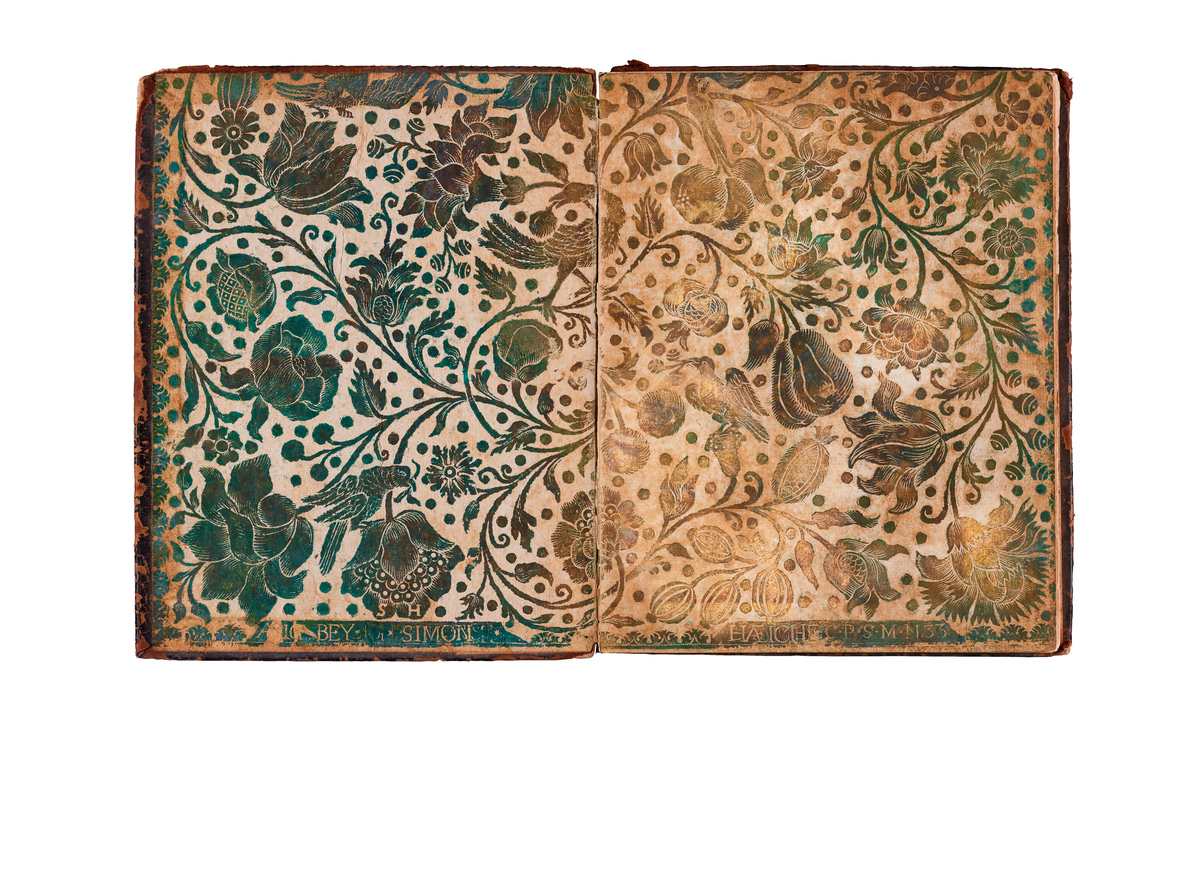

The purchaser of this negative-embossed floral brocade paper employed it as the cover for a book published in 1781.

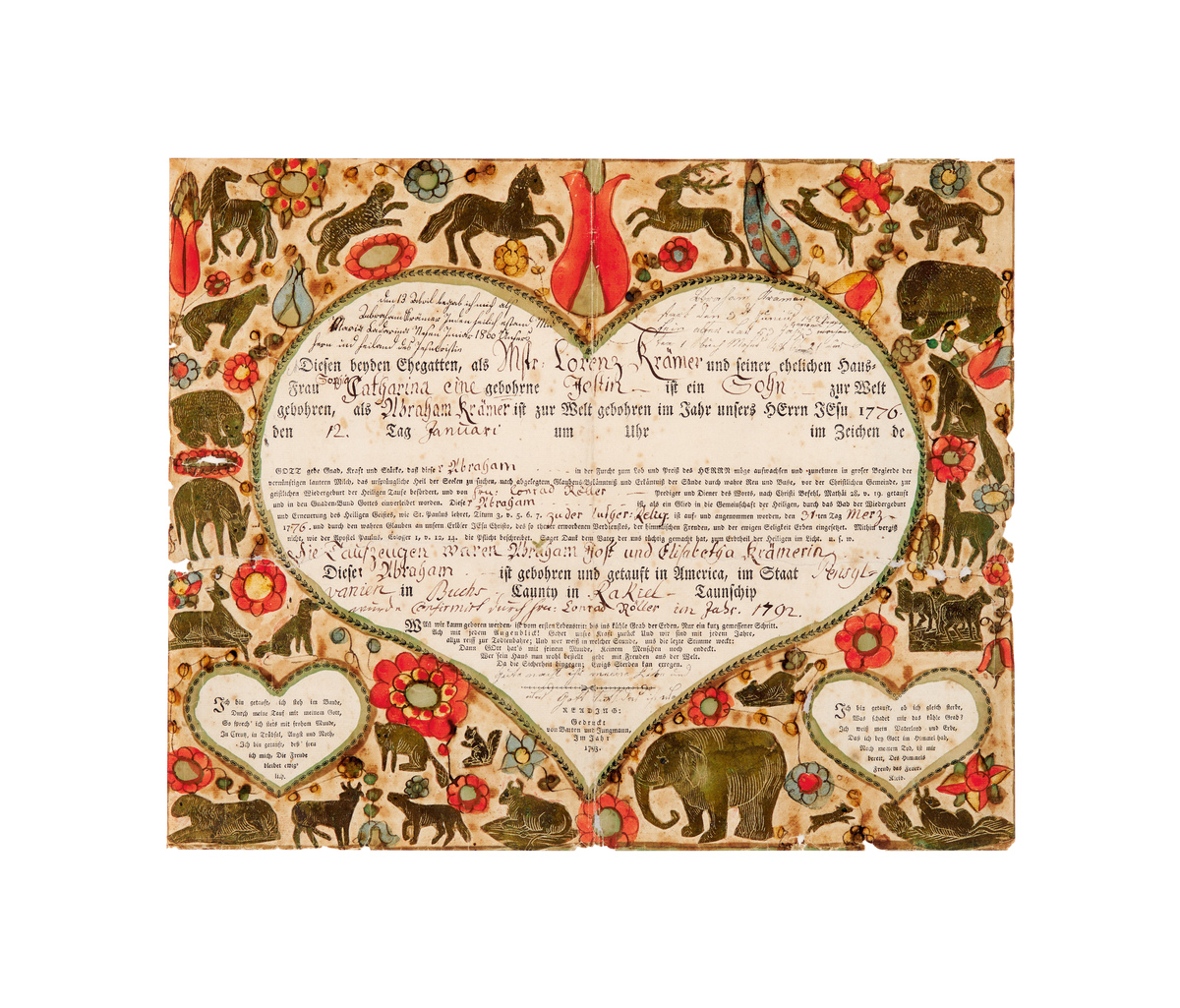

Goethe’s sheets with “golden animals” had emerged after decades of stylistic and technological development in continental Europe. Following the popularity of marbled “Turkish papers” created in Venice in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, printers in southern Germany in the late seventeenth century began to experiment with creating an array of colored, stamped, and marbled decorative papers for use as endpapers for books, drawer linings, and wallpaper.14 Germans of the period classified all such decorative papers beneath the umbrella-term of Buntpapier, or colored paper.15 Among these papers, one style was regarded as aesthetically superior to the others. The term Brokatpapier, or brocade paper, appeared in the 1690s in Augsburg and referred specifically to papers embossed with metallic foils. Depending on their decoration, these papers might resemble either intricate brocade textiles or the gilt-leather wall coverings popular throughout the seventeenth century.16

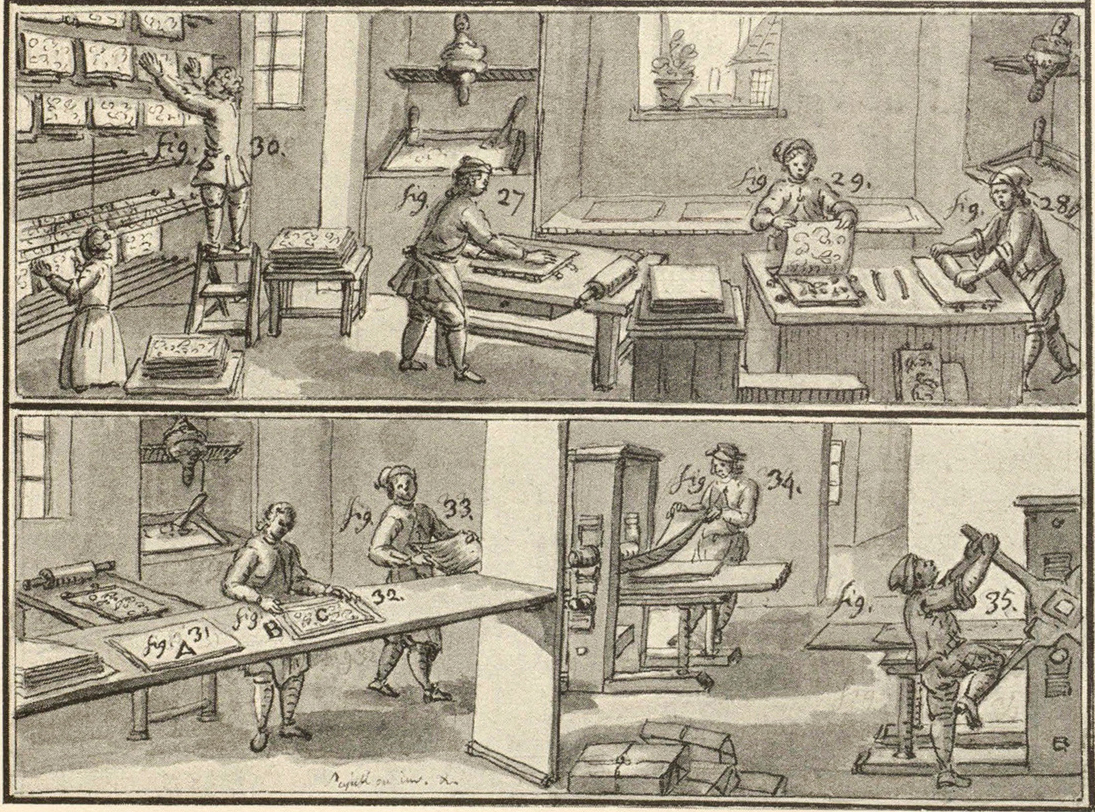

The creation of brocade paper drew upon techniques for creating embossed leather and wallpapers (fig. 7). A printer’s assistant first colored sheets of paper with broad, painterly brushstrokes. A striking red oxblood-based paint was popular in the early eighteenth century, but by mid-century other colors such as yellow, blue, and green became common. Meanwhile, the Formschneider (block cutter) had carved the desired pattern from a metal plate, which was cut either in a positive embossing to leave a gilt design on a colored background or a negative embossing in which the lines of the design itself were carved out, leaving a colored motif on a gilt background. Positive embossing was popular for figural scenes and negative for abstracted floral patterns (see figs. 5, 6). After the carved metal plate was warmed, a damp sheet of colored paper, primed with adhesive egg white and covered with the metal leaf, was laid on top. The materials then passed through the rolling press.17 Under its pressure, the metal leaf adhered to the raised sections in the paper and the unbonded leaf was later brushed off.18 These metal foils rarely included genuine gold and silver; rather, they were typically copper or tin alloys mimicking more expensive precious metals.19 As is evident on surviving objects, these chemically reactive lesser metals have frequently oxidized due to extended exposure to air.

Thomas Dundas

Has just stocked from the last ship from Europe a splendid and handsome assortment of

Dry Goods

Which he is selling for reasonable and inexpensive prices. He also has for sale a great

Diversity of overall splendid

Printed Paper

For lining Parlors and other uses, at a notably low price, and also other useful wet

goods of all varieties and of the best quality.25

Dundas’s advertisement provides insight on the importation of German decorative papers into the United States. That Dundas, a merchant of fine domestic goods, sold these brocade papers rather than booksellers, stationers, or other purveyors of printed wares is significant, highlighting both the elevated nature of these objects and their role not as stationery but as fine goods intended for use within the household. Additionally, Dundas’s phrasing of “printed paper” deviates from typical German and English terminology of the period, highlighting the mutability of language surrounding these novel decorative papers. As Dundas was not himself a German speaker, he likely relied upon the newspaper publisher to translate his advertisement into German, perhaps introducing the source of the error.26 Moreover, in previous advertisements in Philadelphia, Dundas had highlighted when his imported goods originated in London specifically, suggesting that his reference to the latest “ship from Europe” signified the brocade papers’ export from Amsterdam rather than England.27 As no other brocade paper suppliers in Reading have been identified, it is likely that Friedrich Krebs purchased his sheets from Dundas. That Krebs’s decoupaged oeuvre consists of a plethora of gilt flowers, birds, trade scenes, animals, and religious figures suggests that Dundas stocked a wide variety of such papers, which he recommended for “lining Parlors and other uses.”

Friedrich Krebs creatively interpreted Dundas’s suggestion for “other uses.” After purchasing these sheets of gilt paper, Krebs began embellishing his printed certificates. An unsold birth and baptismal certificate at the Newberry Library provides insight into Krebs’s technique (fig. 14). In short, Krebs would carefully excise individual figures from a sheet of brocade paper, arranging and pasting these onto the surface of a certificate. Locations in which watercolors accidentally spill over onto the brocade papers suggest that Krebs arranged and pasted the golden figures before watercolor illumination. The careful nature of Krebs’s cutting—by either scissors or penknife—is highlighted by the crowded nature of figures on the original sheets of brocade paper; great care would have been required to excise a figure without damaging its neighbors.28 Krebs did not necessarily maintain absolute fidelity to each brocade paper figure; on the Newberry Library’s trade-scenes certificate, for example, Krebs has separated a portraitist from his model, though he pasted both onto the same certificate (see fig. 12). Krebs universally preferred symmetry in arranging his brocade papers, balancing his favored bird and flower motifs on both sides of the heart-printed certificates and frequently positioning saints in rectangular frames at their corners (fig. 15). Krebs was also not averse to nationalistic imagery as he included turkeys and eagles grasping branches in a manner reminiscent of the Great Seal of the United States. The turkeys also offered an opportunity for playfulness: in one case, he balanced a female turkey with a male on either side of a certificate, a nod to the certificate’s role in celebrating and recording a family’s growth (fig. 16).

Figure 17 Friedrich Krebs, birth and baptismal certificate of Jacob Jost, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, c. 1797. Watercolor, ink, and applied brocade paper on paper, W. 13 in. The Free Library of Philadelphia, FLP 265

Note that losses to the watercolor ground at the bottom right suggest that pasted brocade paper birds have since fallen off the certificate.

While known period accounts of consumers’ interactions with Krebs’s decoupage fraktur exist in the historical record, surviving objects suggest delight in the artist’s technique. Young Goethe’s account, previously discussed, shows that children were charmed by the “golden animals” on brocade paper, and it is likely that American children were no different. Such is suggested by a decoupage reward of merit fraktur attributed to Krebs and today at the Winterthur Museum (fig. 19). This diminutive example, the only known decoupage by Krebs that is not a birth and baptismal certificate, was a reward from a schoolmaster to a child for good behavior or academic excellence.30 Its survival and the presence in Krebs’s probate inventory of piles of brocade papers, termed “pictured papers,” suggests that the artist had a steady supply of such papers throughout his life, utilizing them both in his birth and baptismal certificates and in the classroom.31 This decoupage reward of merit is matched by a similar object created in 1792 by Friedrich Ernst, a little-known contemporary of Krebs, who applied a brocade paper eagle onto a small fraktur presented to Barbara Schwartzwalder (fig. 20). Ernst, unlike Krebs, more delicately excised his image, articulating each individual feather and freeing the bird’s outline of jagged edges before pasting it and penning religious text. Ernst’s fraktur, like that of Krebs, suggests that decoupaged brocade papers appeared not only on the birth and baptismal certificates purchased by adults but also enchanted young German-speaking schoolchildren and played a wider, if unacknowledged, role in other fraktur genres.

In both the German American classroom and home, decoupage fraktur pleased the eye in melding materials both traditional and novel. Yet such objects also invite connections with wider Anglo-American fashions in the young United States. Scholars have long traced the emergence after 1790 of “Fancy,” an aesthetic movement that viewed everyday objects as offering opportunities for creative expression. Fancy marked a “growing receptivity to virtually every form of creativity rooted in the imagination,” as Sumpter Priddy has noted, and the term could be applied to an array of painted furniture, metalware, ceramics, textiles, or other decorative or utilitarian objects with surface details that displayed artistic creativity and emotion.32 Wallpaper was perhaps the most common type of Fancy decor, as technological advances in printing wallpaper in rolls rather than as sheets encouraged a greater range of non-repeating patterns and visual detail.33 As wallpaper and brocade paper had been linked since the latter’s origins in the seventeenth century, consumers also associated brocade paper with emergent preferences for Fancy, a connection explicit in period accounts.34

Makers and consumers aligned decoupage, too, with Fancy.35 Such is suggested by early nineteenth-century band boxes decoupaged by young women from rolls of wallpaper and, even closer to Krebs’s fraktur, a remarkable decoupage glassichord at Old Sturbridge Village embellished with golden brocade paper figures (figs. 21, 22). Such objects resonate with Krebs’s decoupage fraktur, and indeed it is possible that Krebs also decoupaged three-dimensional objects. The artist’s estate inventory notes the presence of band boxes followed by “stamp’t” papers, suggesting that the two were used together.36

Recent scholarship on ephemera helps us to understand the relationship between Fancy and the large corpus of Krebs’s decoupaged objects. Over the past two decades, scholars have increasingly addressed the materiality of printed objects previously overlooked. Those scholars tracing early nineteenth-century American collage and decoupage have marked period ephemera as objects that appealed to the transformative power of the individual consumer’s creative hand in cutting, pasting, and otherwise transforming them, rather than simply as reflections of the industrialization and the mass-production of prints. As such, prints of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century existed in what Christina Michelon has termed an “operative tension,” simultaneously objects of mass-production yet also items that consumers might personalize and remake via haptic interaction.37

Krebs’s decoupage fraktur finds a promising, yet also complex, position in such scholarship as “operative tensions” are multiply layered in the artist’s corpus. In his decoupage certificates, it is hardly difficult, of course, to locate the creative role of the artist’s imagination and hand; he artfully transformed each mass-printed brocade paper sheet and, through decoupage, arranged the images into playful scenes interacting with one another and the surrounding watercolors. Perhaps just as significant, as the designer of his mass-printed, three-heart birth and baptismal certificates, Krebs was himself employing decoupage as a means through which to transform the very mass-produced certificates that he had designed and coproduced with printers. Thus, while each decoupaged certificate was unique, each was itself the result of a time-saving technique that transformed the act of decoupage into one of mass-production.38 As such, Krebs’s decoupaged oeuvre sits only uneasily beside the work of the young, female amateur artists typically studied by scholars of period collage and decoupage.

Krebs’s practice of decoupage over a twenty-year period suggests that his wares were popular among German-speaking consumers besot with Fancy. To this point, a final question remains: as Fancy objects that delighted the eye through exuberant surface treatment, how did Krebs’s decoupage fraktur function within the German-speaking domestic environment? Unfortunately, a definitive answer remains elusive. The most common treatment for birth and baptismal certificates was folding and storage within a family bible or chest, keeping safe a family’s collective memory but also hiding fraktur from casual viewership.39 Yet here the highly oxidized gilding on Krebs’s decoupage certificates is valuable evidence. Exposure to air degraded the copper and tin alloys comprising these gilt papers, turning faux gold and silver to black; even the versos of such objects frequently reveal copper-oxide staining from the recto. Such corrosion contrasts with those brocade papers used as endpapers in books, a storage condition that ensured that gilding remained safe from exposure to air and preserved the sensitive alloy (fig. 23). Unlike these endpapers, the high degradation of Krebs’s decoupage certificates suggests that purchasers did not typically fold and store them within family bibles, although whether German American families framed and displayed these certificates remains difficult to determine.

Figure 23 Simon Haichele (fl. 1740–50), floral brocade paper used as endpapers, c. 1750–80. The German Society of Pennsylvania, Henry Keppele family record book, c. 1780–1843, Ms. Coll. AM 625.2 (Photo: Jürgen Altmann)

These endpapers are in the family book of Johann Heinrich Keppele (1716–1797), a Philadelphia merchant and the first president of the German Society of Pennsylvania.

Acknowledgments

About the Author

1 See, for example, the exhibition catalogue by Holger Cahill, American Folk Art: The Art of the Common Man in America, 1750–1900 (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1932), 17.

2 Henry Chapman Mercer, “The Survival of the Mediæval Art of Illuminative Writing among Pennsylvania Germans,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 36, no. 156 (1897): 425; J. H. Carlson and John Krill, “Pigment Analysis of Early American Watercolors and Fraktur,” Journal of the American Institute for Conservation 18, no. 1 (1978): 19–32.

3 Use of the term decoupage is nuanced. In part, this essay follows the recent work of Christina Michelon in broadening the scope of decoupage (from the French, decouper, meaning “to cut out”) from its twentieth-century association with craft practices to a wider framework of “prints that are cut out, arranged and pasted onto a three-dimensional object.” While fraktur are not three-dimensional objects, this definition is a closer fit than collage (from coller, “to paste”), which refers to the pasting of prints from different sources onto one surface. The visual homogeneity of pasted brocade papers was important to the fraktur artist (i.e., the pasted figures typically originated from the same sheet). See Michelon, Interior Impressions: Printed Material in the Nineteenth-Century American Home (PhD diss., University of Minnesota, 2018), 36–37.

4 Donald A. Shelley, The Fraktur-Writings or Illuminated Manuscripts of the Pennsylvania Germans (Allentown: Pennsylvania German Folklore Society, 1961), 126. More recent scholarship has identified at least 480 individual examples of Krebs’s surviving birth and baptismal certificates. See Corinne Earnest and Russell Earnest, The Heart of the Taufschein, Fraktur and the Pivotal Role of Berks County, Pennsylvania (Kutztown: Pennsylvania German Society, 2012), 73.

5 Frederick S. Weiser, “Ach wie ist die Welt so Toll! The Mad, Lovable World of Friedrich Krebs,” Der Reggeboge 22, no. 2 (1988): 49.

6 “Kreps, Friedrich (* ca. 1749),” Hessische Truppen in Amerika, January 20, 2015, https://www.lagis-hessen.de/en/subjects/idrec/sn/hetrina/id/1733.

7 See accounting entries for December 1797, March 1798, May 1798, November 1799, and September 1800, Jacob Schneider Day Book, 1797–1816, Berks History Center Library, Reading, PA.

8 Weiser, “Ach wie ist die Welt so Toll,” 49–51.

9 Shelley, Fraktur-Writings, 126–28.

10 Krebs worked with several Reading-based printing firms in the 1790s, including Thomas Barton and Gottlob Jungmann, Jungmann and John Gruber, Gottlob Jungmann, and Jacob Schneider and Co. He later worked with Johann Ritter of the Reading Adler. See Shelley, Fraktur-Writings, 145. For a narrative of Krebs’s project with Reading-based printers in designing his three-heart certificate, see Earnest and Earnest, Heart of the Taufschein, 73.

11 This development was surprisingly complex given the need for the rectangular lettertype composed into a curved heart to remain balanced under the pressure of a screw press. See Earnest and Earnest, Heart of the Taufschein, 73.

12 Albert Haemmerle, Buntpapier: Herkommen, Geschichte, Techniken, Beziehungen zur Kunst (Munich: Georg D. W. Callwey, 1977), 20.

13 Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Aus meinem Leben: Dichtung und Wahrheit, ed. Karl Heinemann (Leipzig: Josef Singer, 1922), 12 (my translation). My gratitude to Simon Beattie for directing me to this passage.

14 Christiane F. Kopylov, Papiers dorés d’Allemagne au siècle des Lumières: Suivis de quelques autres papiers décorés (Bilderbogen, Kattunpapiere & Herrnhutpapiere), 1680–1830 (Paris: Éditions des Cenres, 2012), 15.

15 In this earlier context, the word Bunt does not have its current translation of “colorful” but more simply “colored.” See Haemmerle, Buntpapier, 11.

16 Kopylov, Papiers dorés d’Allemagne, 10.

17 Using a rolling engraver’s press rather than a screw press ensured a more even distribution of pressure over the large surface area of brocade paper sheets. See Haemmerle, Buntpapier, 80.

18 Simon Beattie, “The Beauty of Brocade Paper,” Engelsberg Ideas (blog), Axel and Margaret Ax:son Johnson Foundation for Public Benefit, July 2, 2021, https://engelsbergideas.com/notebook/paper-brocade-beauty/; Haemmerle, Buntpapier, 80–89; Angela Meincke, Chris White, and Kim Nichols, “Decorative and Functional Uses of Paper on Furniture,” in Postprints of the Wooden Artifacts Group, Presented at the 31st Annual Meeting of the American Institute for Conservation Arlington, Virginia (Arlington, VA: American Institute for Conservation, 2003), 74–75.

19 Kopylov, Papiers dorés d’Allemagne, 18.

20 Twenty-four Buntpapier printers operated in Augsburg throughout the eighteenth century and twelve in Nuremberg. See Haemmerle, Buntpapier, 22.

21 Printers who copied Munck are easily identified as their printed sheets horizontally flipped the image, the result of copying a printed object onto a copperplate. Known pirates of Munck’s trade scenes include Paul Raymund of Nuremberg and Johann Georg von Eckart. See Kopylov, Papiers dorés d’Allemagne, 21.

22 Christa Pieske, “The European Origins of Four Pennsylvania German Broadsides Themes: Adam and Eve; The New Jerusalem–the Broad and Narrow Way; the Unjust Judgment; the Stages of Life,” Der Reggeboge 23, no. 1 (1989): 7.

23 See “To be sold, at Charles Hargrave’s . . .,” Pennsylvania Gazette (Philadelphia), March 27, 1746.

24 Klaus Stopp identified this advertisement in The Printed Birth and Baptismal Certificates of the German Americans (East Berlin, PA: printed by the author, 1997), 1:79.

25 Thomas Dundas, “Thomas Dundas hat so eben mit den letzten Schiffen . . .,” Neue Unpartheyische Readinger Zeitung und Anzeigs-Nachrichten (Reading, PA), May 1, 1793 (my translation).

26 German-language newspapers often offered to advertisers the complimentary service of translating advertisements from English to German. German-speaking printer Henry Miller, for example, noted that English advertisements were “by him translated gratis.” See Miller, “Henry Miller has moved his printing office . . .,” Pennsylvania Gazette, June 13, 1771.

27 See, for example, “Just imported in the last vessels from London . . .,” Pennsylvania Gazette, June 5, 1760.

28 Krebs may have used either scissors or a knife in his craft. Period silhouette artists used both, typically choosing whichever was readily accessible. The finest silhouettes required a specialized knife, as scissors are clumsy in excising minute areas of paper, but Krebs did not cut his decoupage papers in enough detail to suggest that he employed a knife or any specialized tools. See Penley Knipe, “Paper Profiles: American Portrait Silhouettes,” Journal of the American Institute for Conservation 41, no. 3 (Autumn/Winter 2002): 225.

29 In 1804—his most active year—Krebs had a total of 1,987 blank certificates printed by the publisher of the Reading Adler. Between 1801 and 1813, the Adler printed 6,974 certificates for Krebs. See Alfred L. Shoemaker, “Notes on Frederick Krebs, the Noted Fractur Artist,” Pennsylvania Dutchman 3, no. 2 (1951): 3.

30 See Shelley, Fraktur-Writings, 51–52.

31 “Krebbs, Frederick, Swatara,” file 34, paper 1, Dauphin County Orphan’s Court Index, Register of Wills Office, Harrisburg, PA.

32 Sumpter Priddy, American Fancy: Exuberance in the Arts, 1790–1840 (Milwaukee: Chipstone Foundation, 2004, xxv.

33 Priddy, 37.

34 Priddy, 24.

35 Priddy, 126.

36 See note 31.

37 See, especially, Michelon, Interior Impressions, 1–2, 31.

38 Corinne and Russell Earnest have also suggested that Krebs may have employed his children in the task of cutting brocade papers. See Earnest and Earnest, Heart of the Taufschein, 94.

39 Jon Charles Acker, To These Parents: A Compendium of Pennsylvania German “Taufscheine” (Marion: Pennsylvania German Society, 2020), 1:19; Earnest and Earnest, Heart of the Taufschein, 15.