Another Look at Johannes Bard

(1797–1861)

Richard Miller

Once called the “Yankee Da Vinci,” Rufus Porter was an itinerant portrait painter and muralist, a publisher and author, an inventor of mechanical improvements, and an impresario who engineered an airship that promised to fly gold rush prospectors from New York to California in three days.

The recent book Rufus Porter’s Curious World: Art and Invention in America, 1815-1860, which was co-edited by Laura Fecych Sprague and Justin Wolff, is organized around major themes in Porter’s life. In this short piece, Laura Sprague offers a taste of the book by focusing on artist-inventors and itinerant artists. She has selected several examples to help place Porter’s pursuits and interests into the larger cultural context of antebellum America. For more information about the book click here. To read an essay about Porter by Laura, click here.

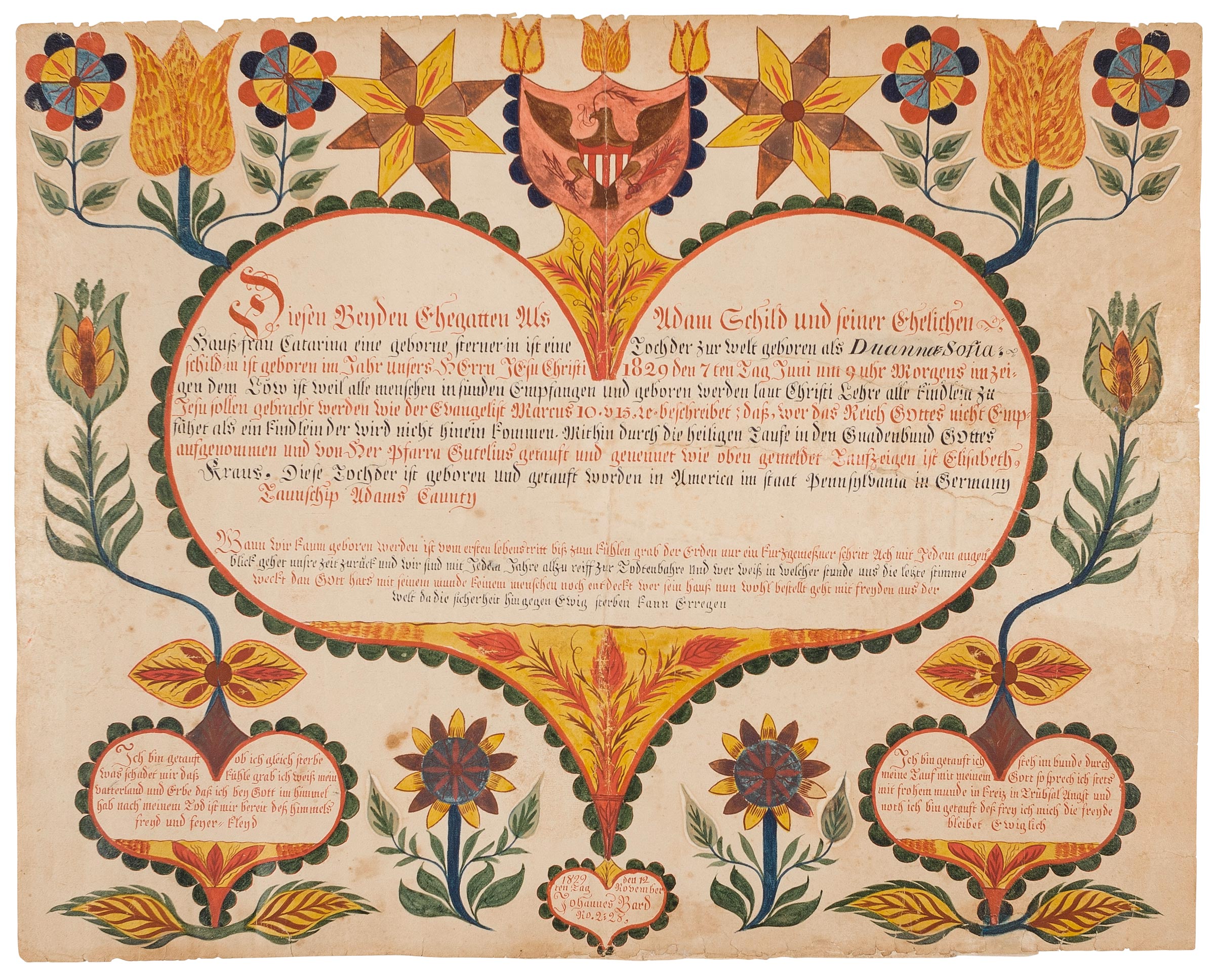

References to Johannes Bard as a fraktur artist first appeared in Donald A. Shelley’s landmark 1961 study, “The Fraktur-Writings or Illuminated Manuscripts of the Pennsylvania Germans.”1 In the succeeding sixty years, interest in Bard’s work has grown, along with the number of examples of his work. The most recent count of fraktur produced by Bard numbers twenty-three baptismal (Taufschein) and birth and baptismal (Geburts und Taufschein) made for individuals in Pennsylvania’s Adams and York Counties, and in Frederick County, Maryland, who were born between 1802 and 1835.2 Bard consistently repeated the same format of his fraktur, routinely signing and often dating his work, making his fraktur readily identifiable (Fig. 1). His methodical study of calligraphy and watercolor painting when he was in his early twenties may have resulted in a much larger body of work. Still, twenty-three fraktur by one artist is not an insignificant number to survive. Dated works span 1827 to 1835, placing Bard’s work in the period that witnessed the transition from fully hand-painted fraktur to printed examples augmented with watercolor.

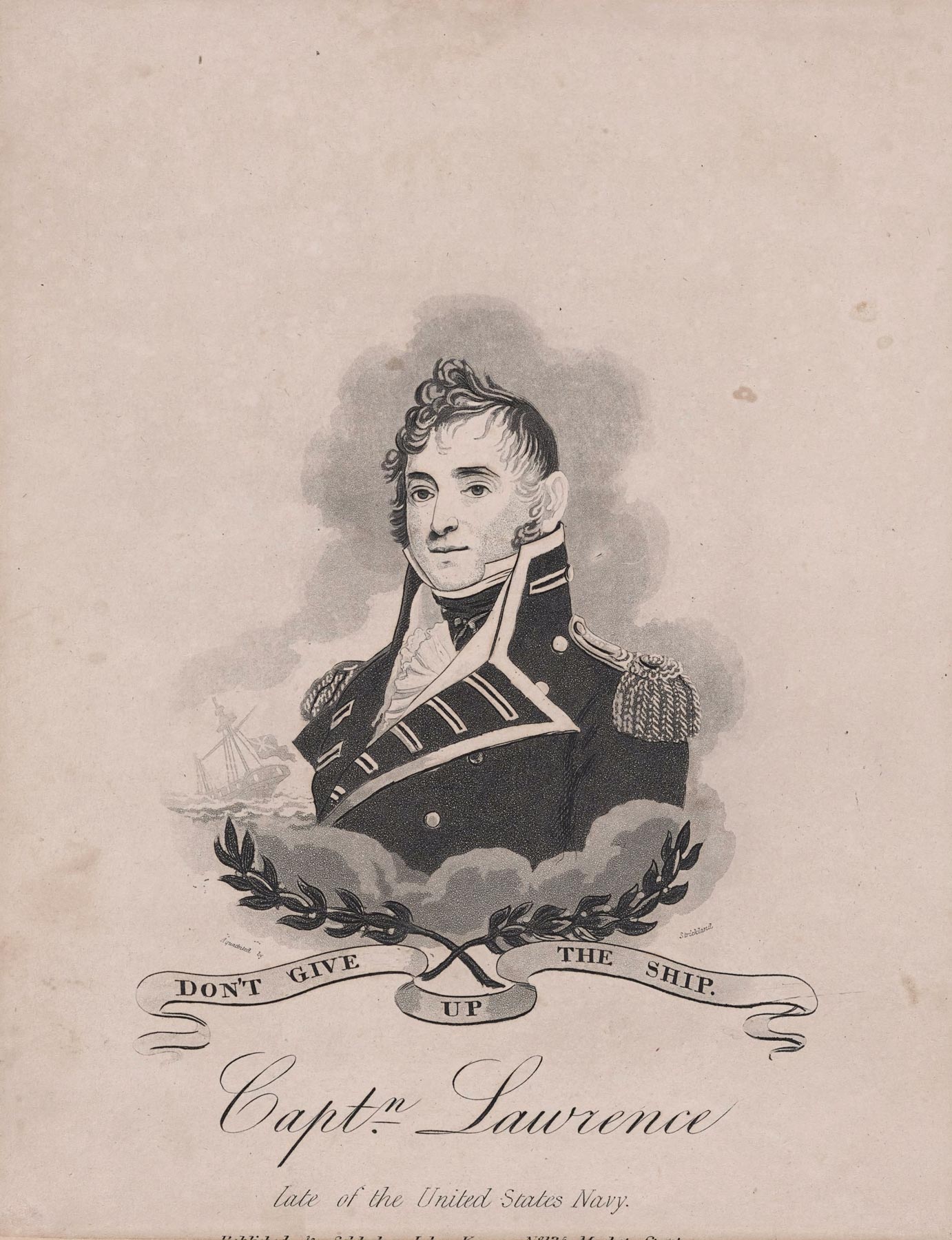

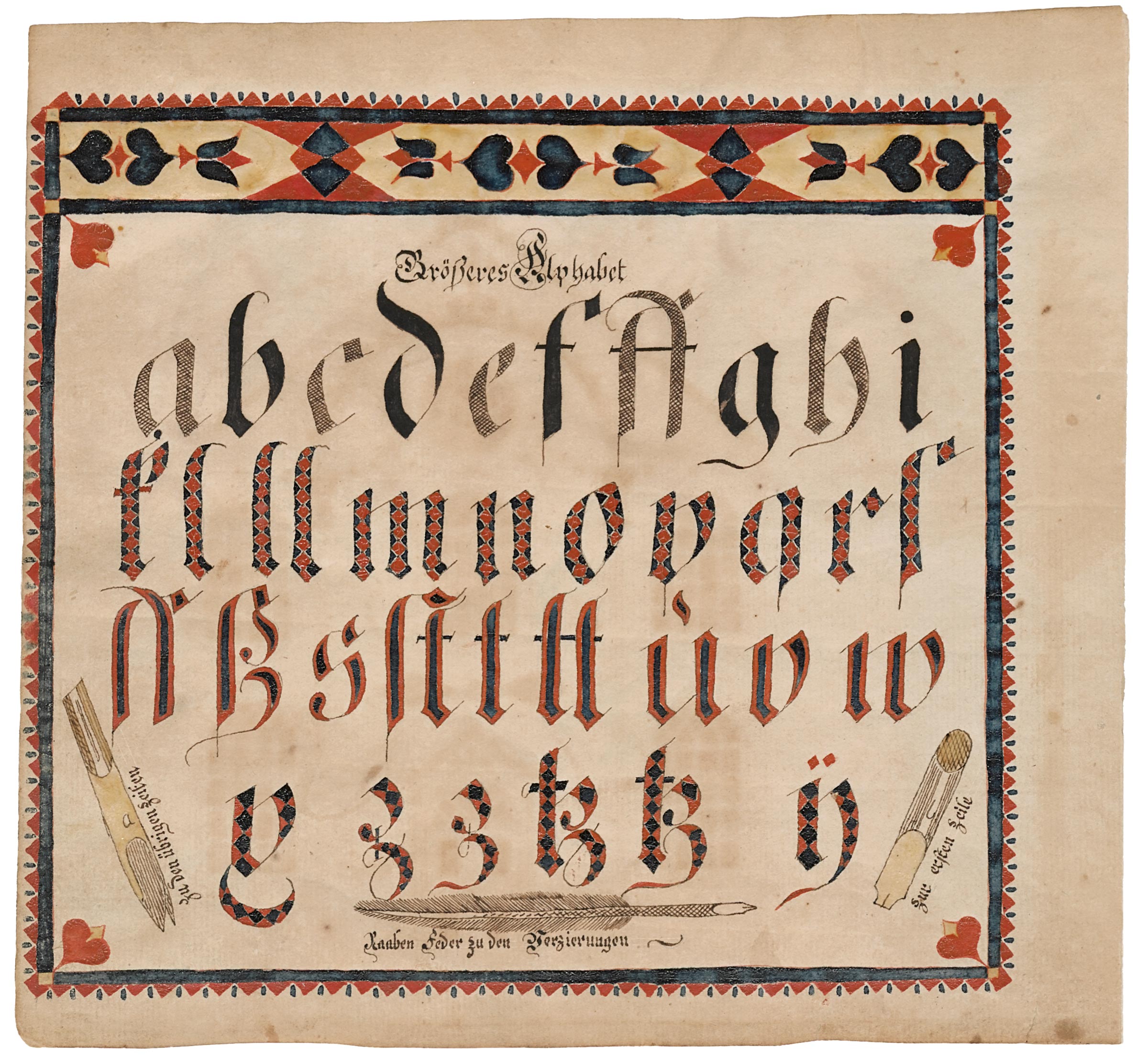

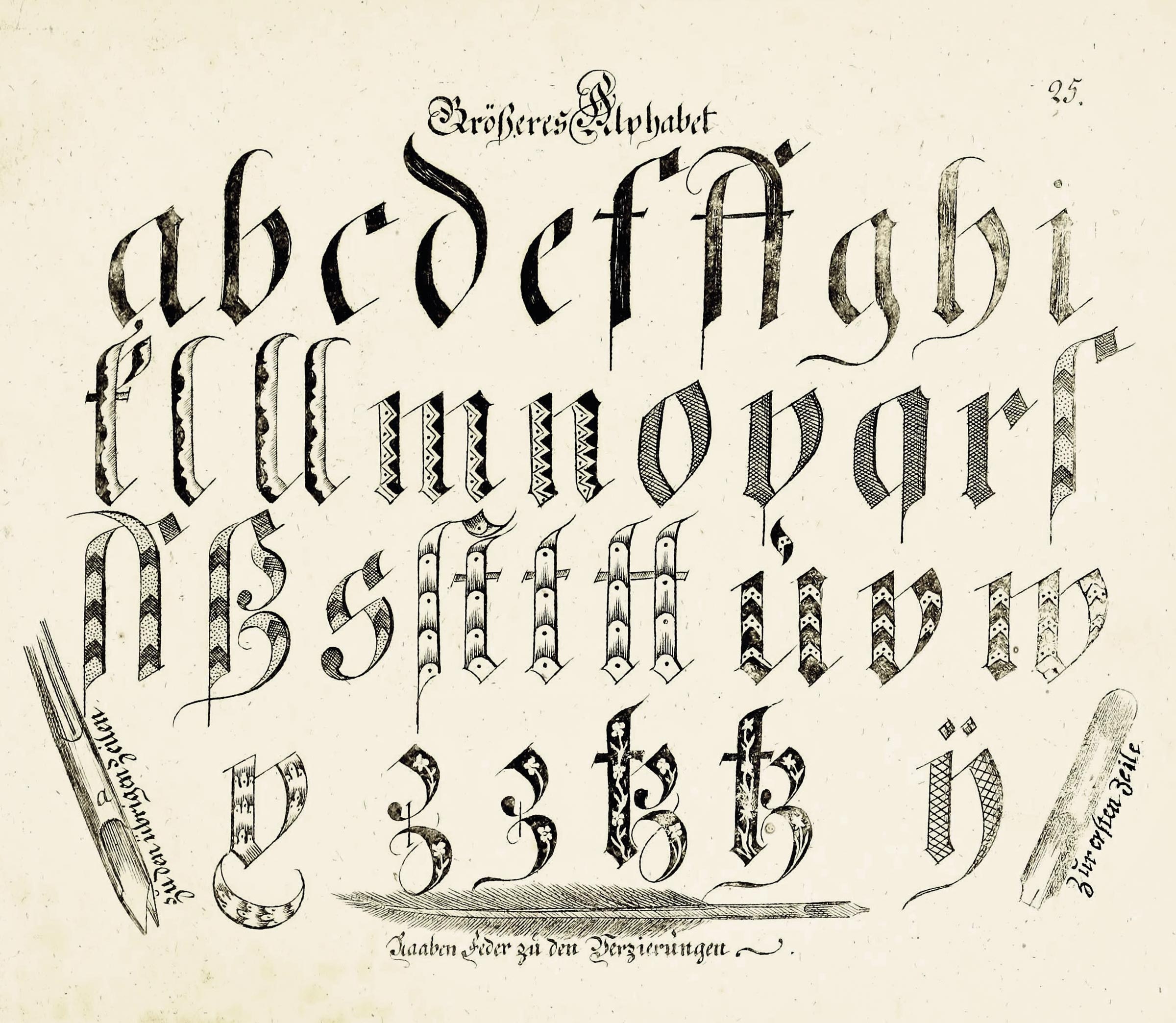

Until the middle 1990s, Bard was thought to have painted only fraktur. Then, forty-eight ink and watercolor drawings that had descended for over 170 years in the artist’s family were found.3 More than doubling Bard’s known body of work, the collection, however, contained no fraktur. Instead, it was comprised of original architectural drawings and landscapes; ornamental pieces; copies of popular engravings of American presidents and military heroes; and copies of illustrations in the German calligraphy manual written by Johann Gottfried Weber in 1780 (Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5).4 Dated works in the collection span 1819–1821, and the sheets were bound together possibly by the artist at a later date, which ensured the preservation of their vibrant colors. With the discovery of this cache of Bard’s earliest artworks, his reputation now rested upon two very different, but closely related, bodies of work.

Born in 1797 in the part of York County, Pennsylvania, that became Adams County in 1800, Bard and his family lived in Germany Township, located in southern Adams County, on the border with Frederick County, Maryland.5 Bard and Maria Baughman (1810–1850) were married at an unknown date, and the couple would have five children.6 By 1846, Bard had moved north to Union Township, and his parents are documented as living there in 1850.7 In addition to the birth of his daughter, Mary Ann, in 1830, the year would be important for Bard for another reason. His name appears in the 1830 Federal Census as “John Bart,” immediately followed by his father, “Philip Bart.” Both father and son had apparently anglicized their names by that year. Changing Johannes to John merely translated his German name to its English equivalent, whereas altering Bard to Bart is so minor a change as to make it seem unnecessary. Anglicizing his name may have helped further Bard’s assimilation into the wider culture. He would be identified as John Bart in newspapers and public records after 1830, but he maintained his German identity in his art, signing his fraktur consistently Johann or Johannes Bard.

The reason for the six-year gap between the last works in Bard’s book of watercolor exercises and the earliest dated fraktur is not known. He conceivably produced fraktur before 1827 which has yet to be located. The 1820 Federal Census lists his father, Philip, and one male between sixteen and twenty-six years of age, which presumably identifies Johannes.8 Bard was living at his parents’ home in Germany Township, devising a program of self-instruction to learn watercolor painting and calligraphy, besides likely working his father’s farm. How Bard obtained a copy of Johann Gottfried Weber’s 1780 calligraphy manual is unknown, but he put it to good use. Applying lessons learned from Weber’s book, he produced fraktur for clients in Pennsylvania’s Adams and York Counties, and in Frederick County, Maryland, as an additional source of income. Bard’s early copywork may be a unique survival of the self-training that other fraktur artists used to gain the skills to create fraktur for the German-American community.

The symmetrical design of Bard’s fraktur features carefully rendered naturalistic motifs and meticulous calligraphy. Varying only in colors, patterns, and occasionally in the flowers depicted, the sheets are centered by a large heart with a scalloped border. Three identical but smaller hearts are placed at the bottom center and corners, with the middle one is reserved for Bard’s signature and date. Letters and numbers in combination, whose significance is unknown, also appear in the signature heart. Inscribed in precise penmanship in the large heart is biographical information about the recipient in nine rows of alternating red and blue ink. Below are four rows of religious text in smaller red ink, and additional religious texts are inscribed in the small hearts at the bottom corners. Across the top of the sheet are large tulip flowers in the corners flanked by circular scalloped flowers and leaves. Eight-pointed stars are placed on either side of the central motif: an eagle taken from the Great Seal of the United States. Holding arrows of war and an olive branch of peace, the eagle and its placement make it a central focus, providing a clear link to the birthplace of the recipient. The eagle and shield appeared in 1827 on Bard’s earliest known fraktur, suggesting perhaps he incorporated this motif about the time he Anglicized his name. By 1827, Bard was providing clients fraktur that proclaimed their American identity and the German-American cultural traditions that defined their community.

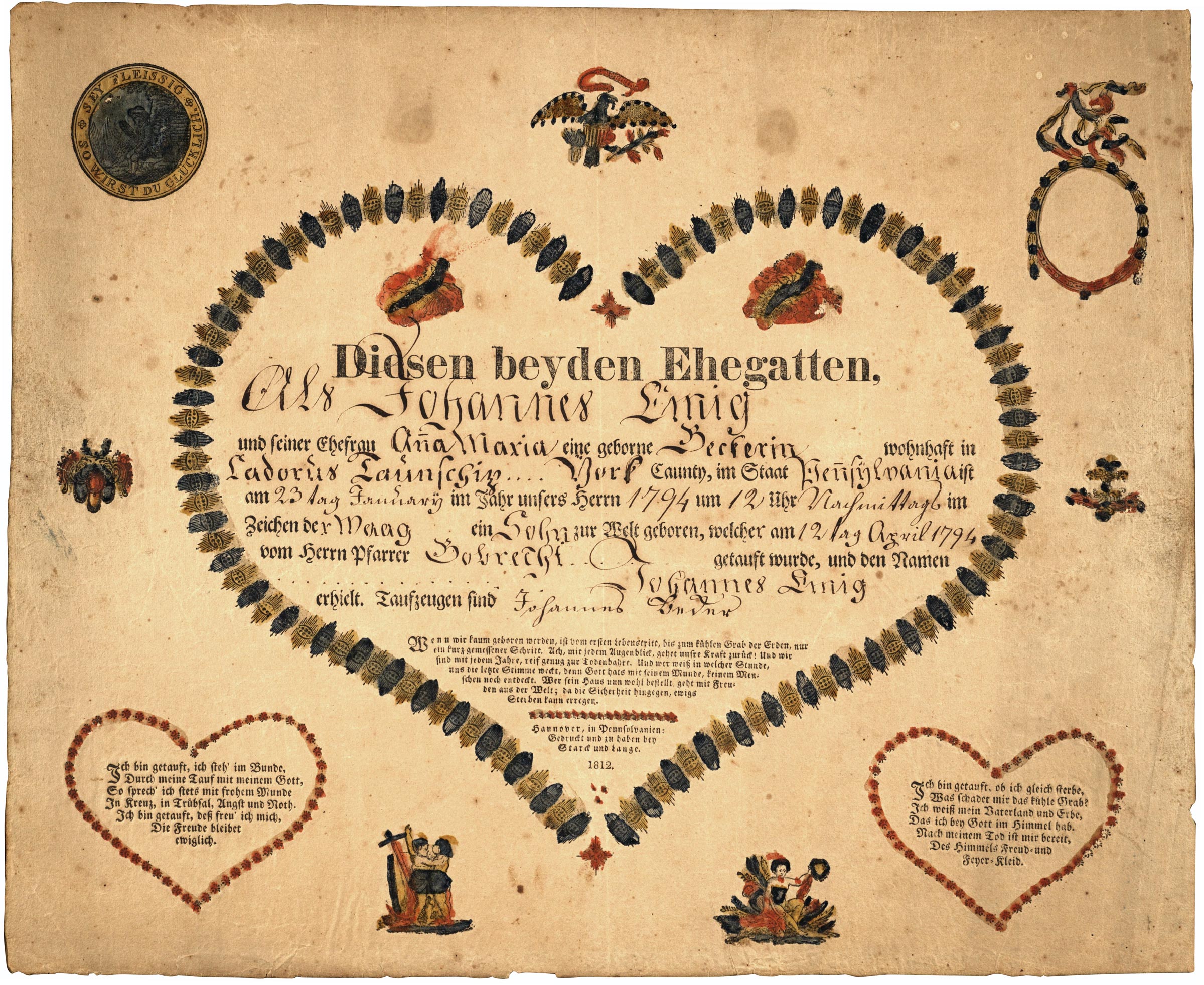

Bard’s composition shows a gradual trend among fraktur artists in combining German and American iconography. He may have first encountered this in printed fraktur produced by printers Johann Starck and Daniel Philip Lange during their partnership in Hanover from 1805 to 1816.9 One design they printed in 1812 bore a large heart in the center, two small hearts in the lower corners, and the eagle from the Great Seal at the top (Fig. 6). Starck and Lange’s prints circulated widely, giving Bard ample opportunities to become familiar with it. Fraktur produced by another local artist, Adam Wuertz (act. 1813–1836), a contemporary of Bard, shows both artists relied on Starck and Lange’s prints for their compositions, with both adding scallops to hearts (Fig. 7). It has been suggested that Bard was a student of George Peter Deisert (act. 1794–c.1815), who also worked in Adams County.10 However, Deisert’s period of activity appears to have ended before Bard completed his earliest known fraktur. Bard may have been familiar with Deisert’s fraktur, but printed fraktur more probably was the basis for parallels in the work of both artists.

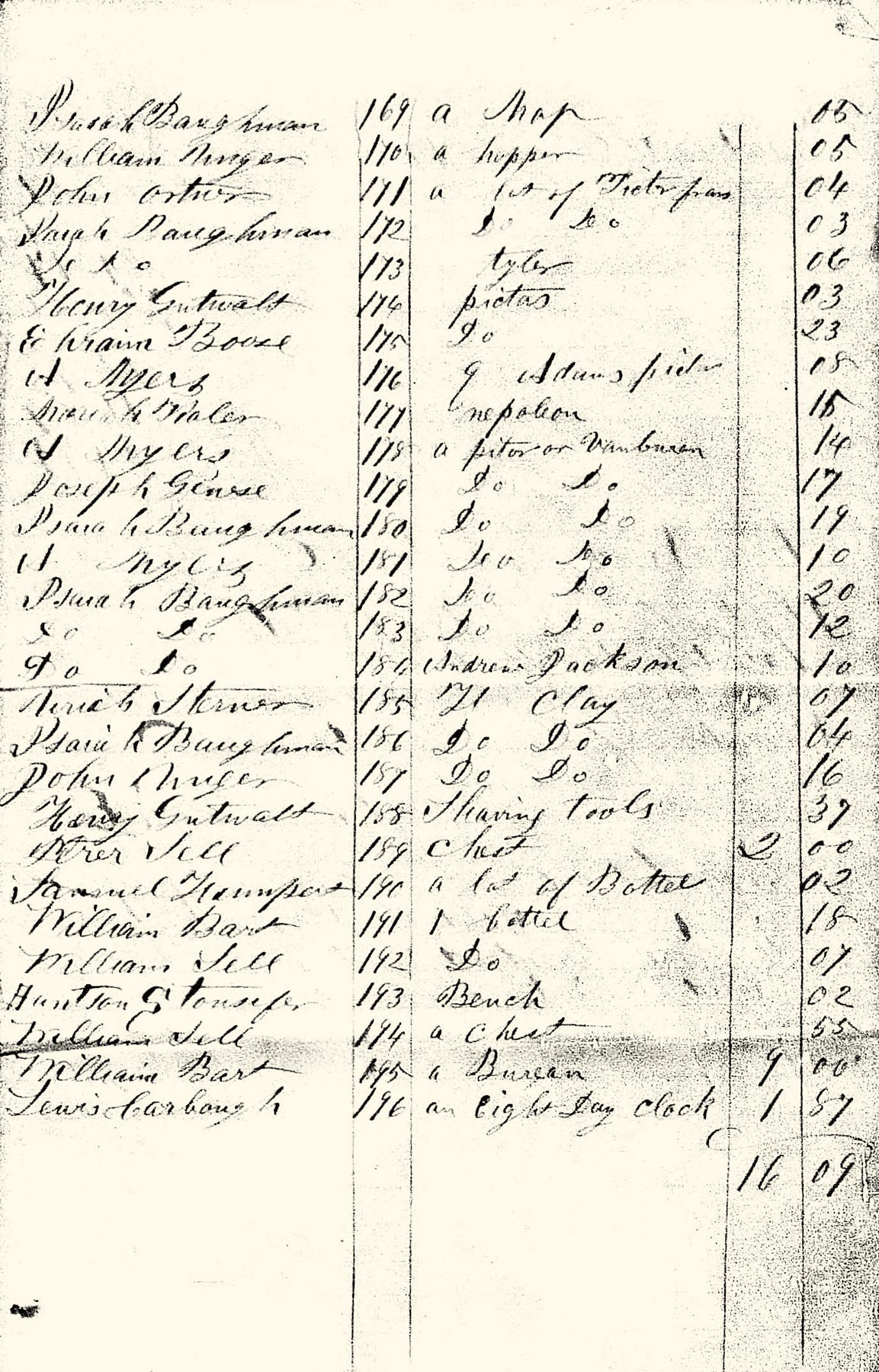

The 1850 Agricultural Schedule for Union Township lists Bard as the owner of a 120-acre farm, of which 100 acres were “improved.” He owned one horse, four milk cows, five sheep, four swine, and fields of wheat, rye, Indian corn, and oats.11 His probate inventory and the list of possessions auctioned included numerous entries for farm equipment, grain, and blacksmith tools—evidence that ironworking generated income besides farming.12 The auction of Bard's possessions included many items that are not usually found among the property of farmers and blacksmiths: “16 pictures and frames”; “a lot of pictures”; and “pictures” of John Tyler, John Adams, Martin Van Buren, Napoleon Bonaparte, Andrew Jackson, and Henry Clay (Fig. 8). Dittos after several of these entries may indicate Bard owned multiple versions of some likenesses. The watercolor drawings he had completed in 1821 included portraits of George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, Andrew Jackson, Oliver H. Perry, James Lawrence, and Zebulon Pike copied from popular engravings, to which Bard added decorative floral borders (Figs. 2, 3).13

Other early works appear to be original compositions. One is a jewel-like depiction of a church resembling the 1787 Basilica of the Sacred Heart of Jesus (Conewago Chapel) in Hanover, York County (Figs. 9, 10). Another is a hunting scene showing a prosperous-looking gentleman standing in the doorway of a stylish house directing our attention to a hunt taking place in the adjacent verdant landscape. The hunter aims his flintlock rifle at an amusingly large black bird perched on the top of a small tree, while two orange dogs wait patiently to retrieve the quarry (Fig. 11). Combining well-drawn naturalistic figures and imaginatively stylized elements, a print source for this image has not been identified.

Thirty years after Johannes Bard’s accomplished early efforts to learn to create carefully composed and vividly colored fraktur were found, he remains the only fraktur artist who left such evidence of the course in self-instruction he devised. His efforts allowed him to use his reputation and personal connections to secure patronage from clients living within ten miles of his home, while also farming and working iron. The central focus of his fraktur is a large heart, a reference to God’s love within Bard’s German-American community. Within the heart, Bard, like his Adams County contemporaries, inscribed the permanent record of the beginning of a child’s secular and religious life.

About the Author

1 Donald A. Shelley, “The Fraktur-Writings or Illuminated Manuscripts of the Pennsylvania Germans” in The Pennsylvania German Folklore Society, (Allentown, PA: The Pennsylvania German Folklore Society, 1961), 13: 32, fig. 77.

2 I am grateful to June Burke Lloyd, Librarian Emerita at the York County History Center, for sharing the list of Bard fraktur she has compiled over the past twenty-five years.

3 David Wheatcroft Antiques, The Authentic Eye: Revisiting Folk Art Masterworks (Westborough, MA: David Wheatcroft Antiques, 2005), fig. 63.

4 Johann Gottfried Weber, Allgemeine Anweisung der neuesten Schönschreibkunst des Hochgräflich Lippischen Bottenmeisters und Aktuarius. Duisburg am Rhein: Helwingschen Universitäts Buchhandlung, 1780.

5 John T. Reilly, History and Directory of the Boroughs of Gettysburg, Oxford, Littlestown, York Springs, Berwick, and East Berlin, Adams County, Pennsylvania (Gettysburg, PA: printed by the author, 1880), 4.

6 The Bard children were Mandilla (1825–1884); Mary Ann (1830–1879); William J. (1833–1910); Lydia C. (1840–1890); and Maria (1845–1931).

7 Bard's presence in Union township by 1846 is verified by a newspaper article listing him as a Grand Juror from the Township. “Grand Jury – April Term,” The Star and Republican Banner (Gettysburg, PA), April 17, 1846: 3. Pennsylvania Newspaper Archive.

8 The 1820 census recorded the number of individuals in households engaged in agriculture, commerce, and manufacture. Two individuals in the Bard household were engaged in manufacture. Bard, and also possibly his father, worked as blacksmiths. “Population schedules of the fourth census of the United States, 1820, Pennsylvania,” Washington [DC]: National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration Collection, Reel 0096-1820 Pennsylvania Federal Population Census Schedules - Adams, Beaver, and Chester Counties, via Internet Archive

9 Russell Earnest and Corinne Earnest, with Edward L. Rosenberry, Flying Leaves and One-Sheets: Pennsylvania German Broadsides, Fraktur and Their Printers (New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Books, 2005), 270.

10 Gerald C. Wertkin, ed., Encyclopedia of American Folk Art (New York: Routledge, 2004), 126.

11 Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, “1850 Federal Agricultural Census: Counties A-J, Union County,” 23. The location of Bard's farm may be approximated from an advertisement in an 1840 issue of the Gettysburg newspaper The Star and Republican Banner which listed lands for sale from the estate of John Kugler. One tract of seventy acres was “…adjoining lands of John Bart, David Sell's Mill property, and others…” The Star and Republican Banner (Gettysburg, PA), October 20, 1840: 3. Additionally, the property of “D. Sell” appears northeast of Littlestown in the northeast corner of Germany Township in an 1858 map of Germany Township, perhaps indicating the general location of Bard's farm before he moved to Union Township by 1850. Map of Adams Co., Pennsylvania (Philadelphia: M.S. & E. Converse, 1858) , Library of Congress.

12 Bard's probate inventory included a “Trasing mashiene [threshing machine]”; winnowing mill; harrow; cultivator; ten acres of wheat; one-half acre of rye; seven acres of oats; and six acres of corn. Also listed are three anvils, numerous hammers, and “a lot of Toungs [tongs].” The auction of Bard's estate conducted on September 28, 1861, included “2 tongs” and “a lot of Blacksmith tools.” Ancestry Heritage Quest, “Pennsylvania, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1683–1993 for John Bart”.

13 Lisa Minardi, Drawn with Spirit: Pennsylvania German Fraktur from the Joan and Victor Johnson Collection (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2015), 328.