American Weathervanes:

The Art of the Winds

The Art of the Winds

The first comprehensive scholarly book on weathervanes

Robert Shaw

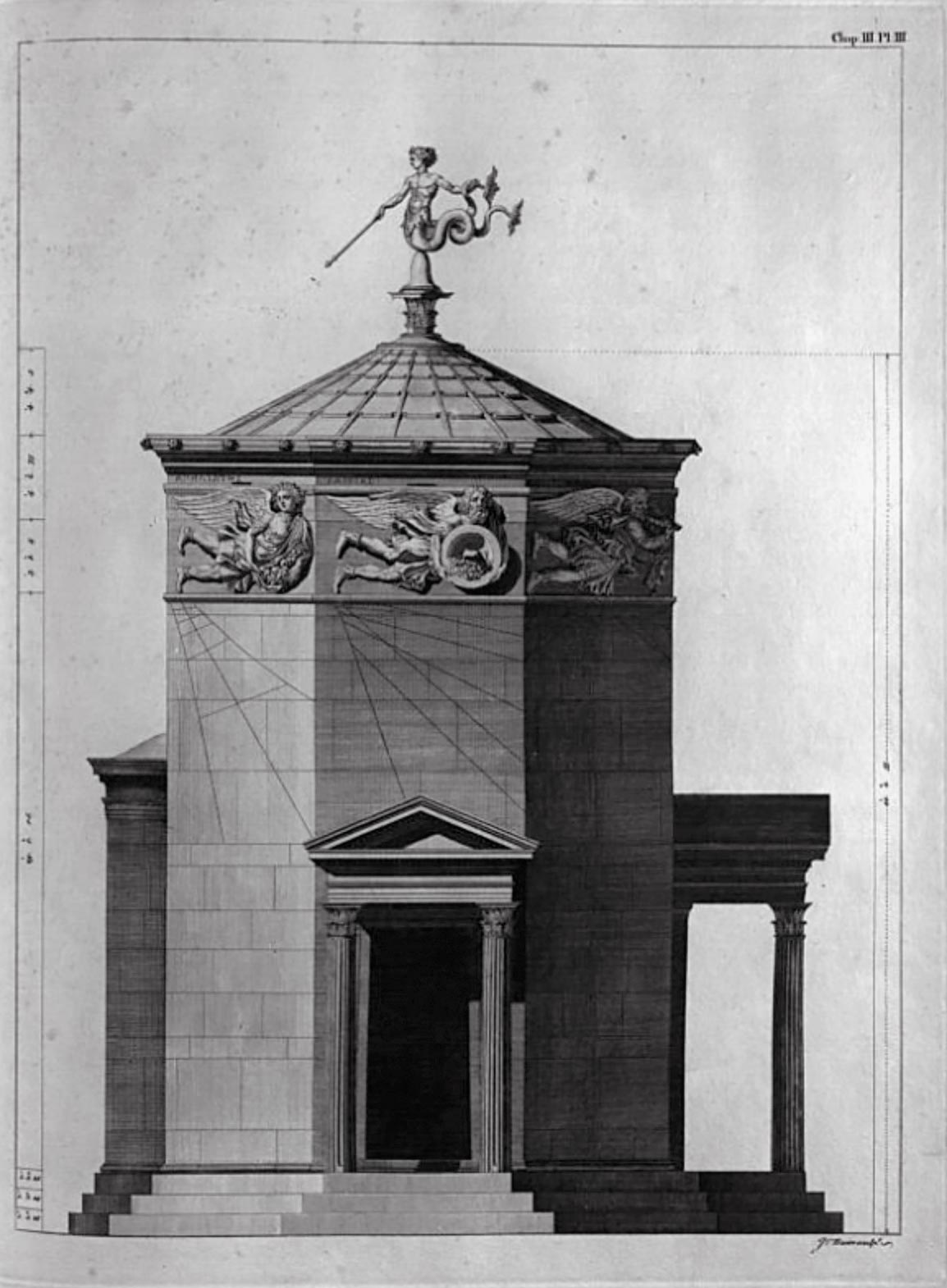

American weathervanes are among this country’s first and most important works of sculptural art. Like most forms of American folk art, weathervanes originated in Europe—the best-documented early vane topped the Tower of the Winds in Athens around 50 BCE—and early settlers brought the concept to this country, where it was democratized and secularized.

From the Tower of the Winds to their apotheosis in post-Civil War America, vanes have always been at once tools, symbolic objects, and works of art, intended for prominent public view and appreciation atop buildings from churches to barns to businesses and civic structures.

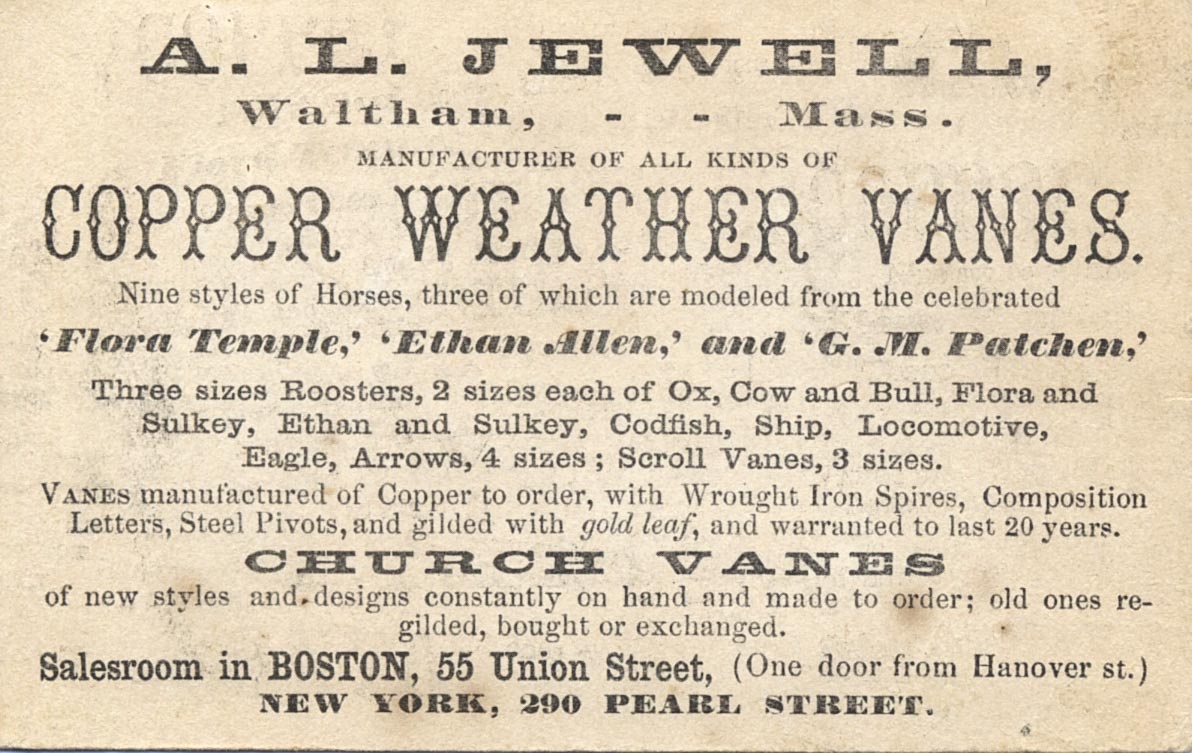

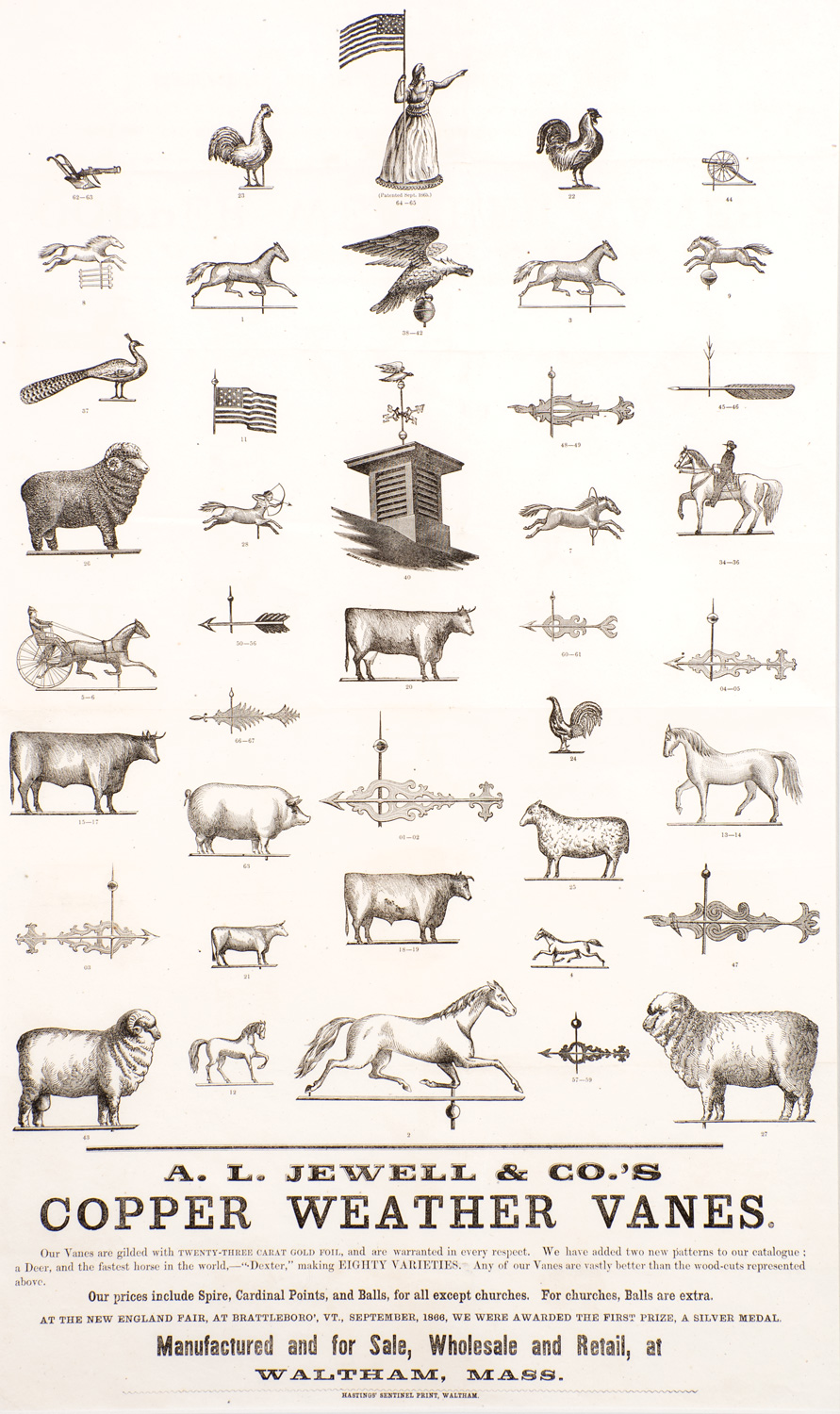

Figure 3

Advertising Broadside. A.L. Jewell & Co., printed by the Sentinel Press. Waltham, Massachusetts. c. 1865. Unframed, 22 ½ x 13 ½ in. Collection of Kendra and Allan Daniel. Photograph by John Currens.

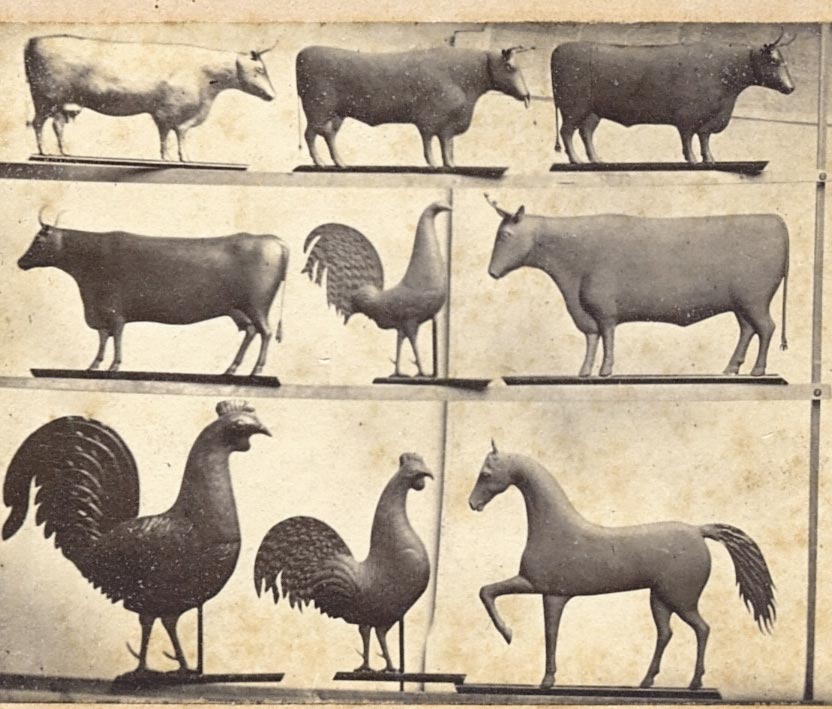

Alvin Jewell was a pioneer in advertising his products, which he promoted through mail order brochures and storefront broadsides with engraved illustrations of the forms he made. Every subsequent company followed his example. A prolific maker as well as an enterprising businessman, Jewell boasted of offering seventy-eight different vane “patterns.” This broadside, which was likely displayed in stores that stocked his wares, illustrates forty of them.

The eclectic and diverse range of forms of American vanes offers a rich mix of the country’s history, spirit, and creative imagination. Vane making became a fulltime business in the years leading up to the Civil War, and a growing number of entrepreneurs published broadsides and catalogues of their wares and sold vanes locally and nationally between 1850 and the early 1900s. Whether made by a single artisan or in a small commercial shop, vane making was a hands-on process that, in the case of a hollow-bodied copper vane, required expertise in design; molding, shaping, and cutting multiple parts; joining them with solder; and finishing the assembled vane with layers of protective and decorative paint or gilding.

American Weathervanes: The Art of the Winds is the title of a recent exhibition that I curated at the American Folk Art Museum in New York in partnership with the AFAM’s wonderful curators Stacy Hollander and Emelie Gevalt. But, it is also the title of my book, which came first and served as the basis for the exhibition. The book is emphatically not a catalogue of the exhibition, which includes only fifty-five vanes, but a separate and much larger entity, a 256-page scholarly publication with 200 stunning photographs of important vanes and fresh, authoritative research. It is the first comprehensive history of weathervanes and the people who made and used them, first in Europe, and then in America, from the colonial era through the early twentieth century.

This is a book that someone needed to write, though I had never thought I would be that someone. For as long as I have been aware of weathervanes as objects of art, which is now over forty years, there has been a conspicuous lack of trustworthy information available about them. Everyone who cared about vanes agreed that deep scholarly research into the history of American vanes and their makers was long overdue, but even as weathervanes steadily rose in stature to rival paintings as the most highly valued folk art objects, no parallel flow of new information took place.

I began to think seriously about a book on weathervanes after Jane Katcher asked me to write an essay about a unique weathervane in her collection, a representation of the Greek goddess Fay-may. That essay, which was published in 2011 in Expressions of Innocence and Eloquence: Selections from the Jane Katcher Collection of Americana Volume II, opened my eyes to the rich possibilities inherent in weathervanes, their history, and their complex, layered meanings. I wanted to learn and write more, so when Jane later asked me if I would be interested in curating a museum exhibition on weathervanes, I, of course, said yes. Then, with her encouragement, I wrote a proposal for a definitive book to go with the exhibition, and ultimately signed a contract with Rizzoli in 2014.

As I started working on the book, I knew I would need help understanding and evaluating the known universe of historic weathervanes. I had neither the time nor the resources to travel to see all the great collections, which were and still are primarily in private hands. Happily, almost all the collectors, curators, dealers, and auctioneers I talked with and visited were excited about the project and offered to help in any way they could. They also thought I was insane to try to tackle such a monster, but they freely shared their expertise, opinions, and contacts, and their ongoing involvement helped refine the project. I will forever be grateful for their help and encouragement.

Chief among them was Julie Lindberg, a longtime collector who had advocated for years for a reliable book on vanes. When I drove to Pennsylvania to visit her and see her collection, Julie connected me with Jennifer Mass, a conservation scientist whose specialty is the study of the surfaces of historic objects. Jen had tested some of Julie's vanes by examining pinhead-sized samples of different parts of their surfaces under an electron microscope. This technique allowed her to see the multi-layered components of each sample and determine how many times the vane had been resurfaced and whether its surface matched historically available materials or used modern chemicals and was possibly intended to deceive. I later convinced Jen to write a chapter about her work and findings for my book. And, after learning more about the project, Julie astonished me by generously offering to support the book by gifting the funding needed to make it a reality to the American Folk Art Museum.

Figure 5

Goat, Northeastern United States, circa 1880. Molded and sheet copper with yellow sizing and gold leaf, 25 by 31 in.; depth of horns, 4 in. Collection of Julie and the late Carl M. Lindberg; photo Gavin Ashworth, courtesy Allan Katz Americana, Madison, CT.

Because of their year-round exposure to wind, soot, and precipitation, weathervanes were often taken down and regilded by their owners. Jennifer Mass’s analysis of this goat’s remarkable surface revealed it has been gilded at least four times over the course of its usage. The weathervane was not stripped between gilding campaigns, and each of the gilders proved to have used period-appropriate materials.

Stacy and I began planning the exhibition in early 2018, with a group of advisors that included Pat Bell and Ed Hild, Allan Daniel, Allan Katz, Jerry Lauren and Sy Rappaport, and David Schorsch, all of whom had been immersed in the weathervane world for decades and seen hundreds more vanes in person than I had or ever would. Their ongoing involvement, along with Julie and Jane’s unflagging support and Jen’s sharp scientific eyes helped refine the project. As is my wont, I absorbed all the information that came my way and kept analyzing and reworking my lists and evolving text. By the time Stacy and I visited Allan and his wife Kendra in New Jersey and Allan looked at me across our lunch table and asked, “So Bob, do you know where all the bodies are buried?” I could truthfully answer, “Yes, I think I do.”

Figure 6

Archangel Gabriel. Gould and Hazlett. Charlestown, Massachusetts, 1840. Gold leaf on iron and copper. 28 1/2 x 71 1/2 x 6 in. Collection of Kendra and Allan Daniel. Photograph by George Kamper.

Beginning in the Middle Ages, Christian churches in Europe were often topped with symbolic weathervanes. The practice was brought to America by early settlers from the British Isles and the Netherlands. The use of the figure of Gabriel, the only angel named in the Bible, became popular in America during the great religious revival of the 1830s and 1840s. This iconic vane was made for the Universalist Church in Newburyport, Massachusetts, and later mounted on the People’s Methodist Church in that town. The body is sheet copper, while the horn is three-dimensional. When the vane was taken down from its historic perch, the horn was found to hold a paper note that identified its makers.

So, you might ask, what is in this magnum opus? It’s hard to summarize such a complex book, but here are a few highlights:

I knew that Boston was the key to the story I wanted to tell. After all, it was home to Shem Drowne, the first documented American-born vane maker, and several of his creations, including his iconic Faneuil Hall grasshopper, are still in situ or on public view in the city, hundreds of years after they were made. Drowne was the inventor of the American weathervane, the first American to make a three-dimensional copper wane, which he completed in 1716, and untold later makers followed his approach.

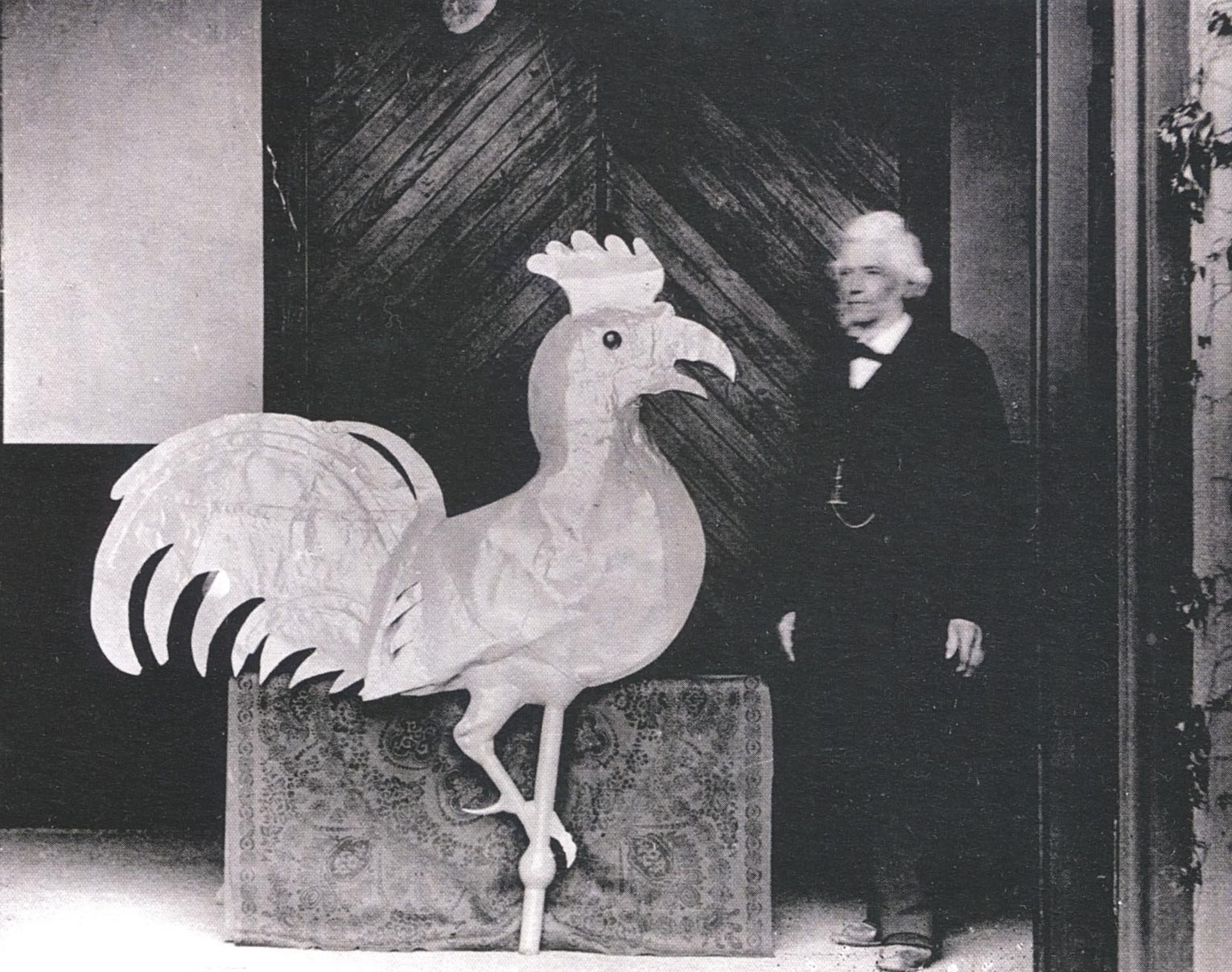

Figure 7

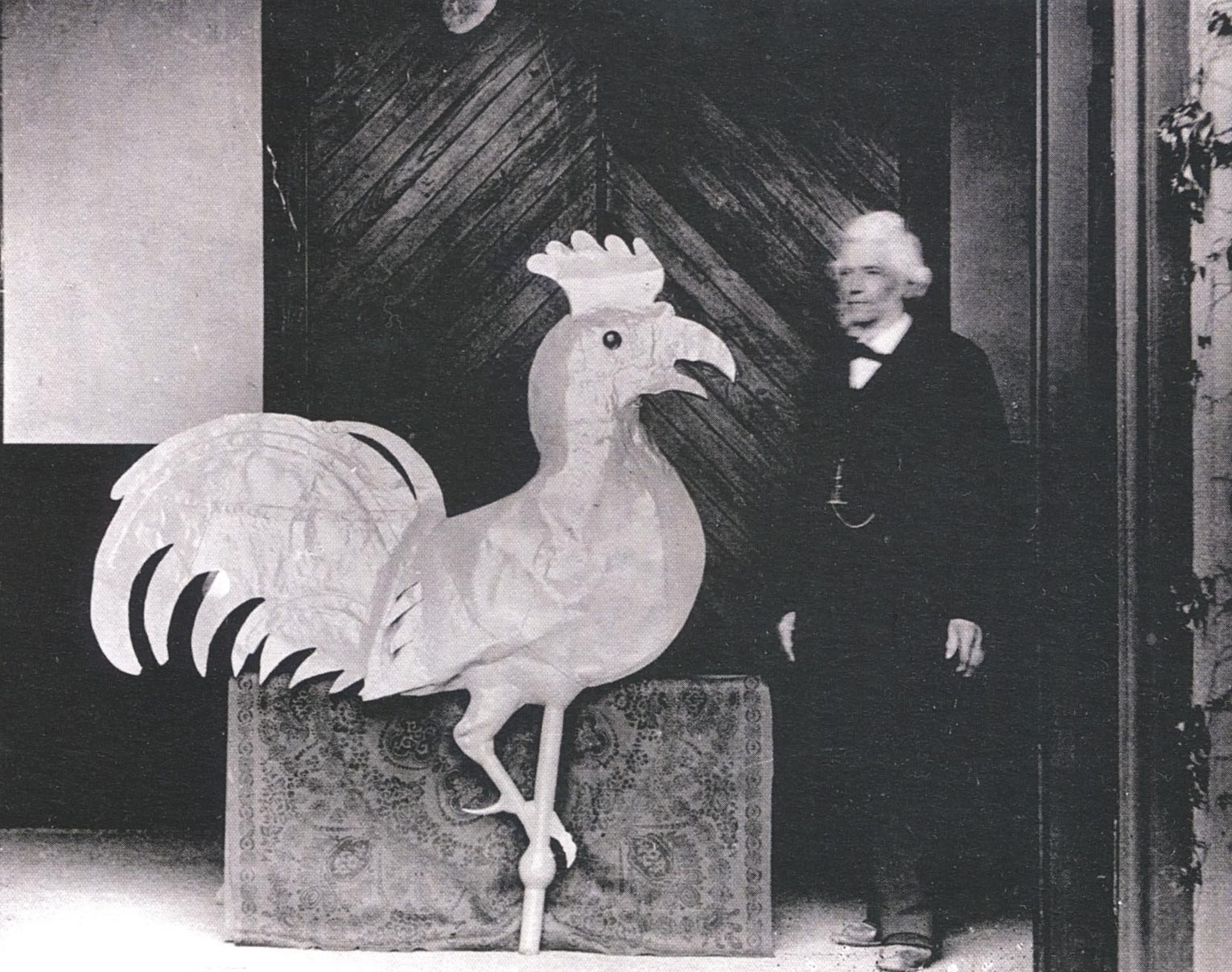

Shem Drowne cockerel and Sexton B. F. Wyeth of the First Church in Cambridge, Congregational, Massachusetts, 1873. Archives of the First Church in Cambridge, Congregational United Church of Christ.

Drowne made this enormous weathercock for a Boston church in 1721. It was moved across the Charles River to Cambridge after the original church was destroyed by a lightning strike, and it still tops the First Church there.

I found new information and stories about Drowne and the enormous importance of his vanes to Revolutionary-era Boston, including a lithograph printed by Paul Revere that shows the Boston skyline seen from the harbor, with churches and public buildings, the skyscrapers of their day, topped by thirteen weathervanes, several of them by Drowne and his sons.

The Industrial Revolution was launched in nearby Waltham, where metalsmith Alvin Jewell started one of the first commercial weathervane businesses in the late 1850s, and, the mysterious Howard family, makers of the most elegant of all American vanes, lived in West Bridgewater, forty miles south of Boston, and were known to have been in business in 1856.

Figure 8

Small rooster. J. Howard & Co., West Bridgewater, Mass., circa 1856–67. Painted and gilded copper and cast zinc, 13 by 12½ by 3 in. Private Collection. Photograph by Gavin Ashworth.

A desire for rooster weathervanes continued well beyond their early Christian origins and into the nineteenth century when most small farmers raised chickens. J. Howard & Co. made roosters in two sizes. This is an example of the company’s far less common small-sized vane.

I discovered that the Howards had been in business at least since 1850, when they were wholesaling their vanes to a farm supply store near Faneuil Hall.

As I suspected, Jewell proved to be the seminal figure in the development of the commercial vane business, another man who set the model for everyone who followed. I found reams of new information about him through the pages of the Waltham Sentinel, whose editor was a friend and fan of “the weather vane man” and chronicled his entire career in the paper, allowing me to tell his story from start to finish.

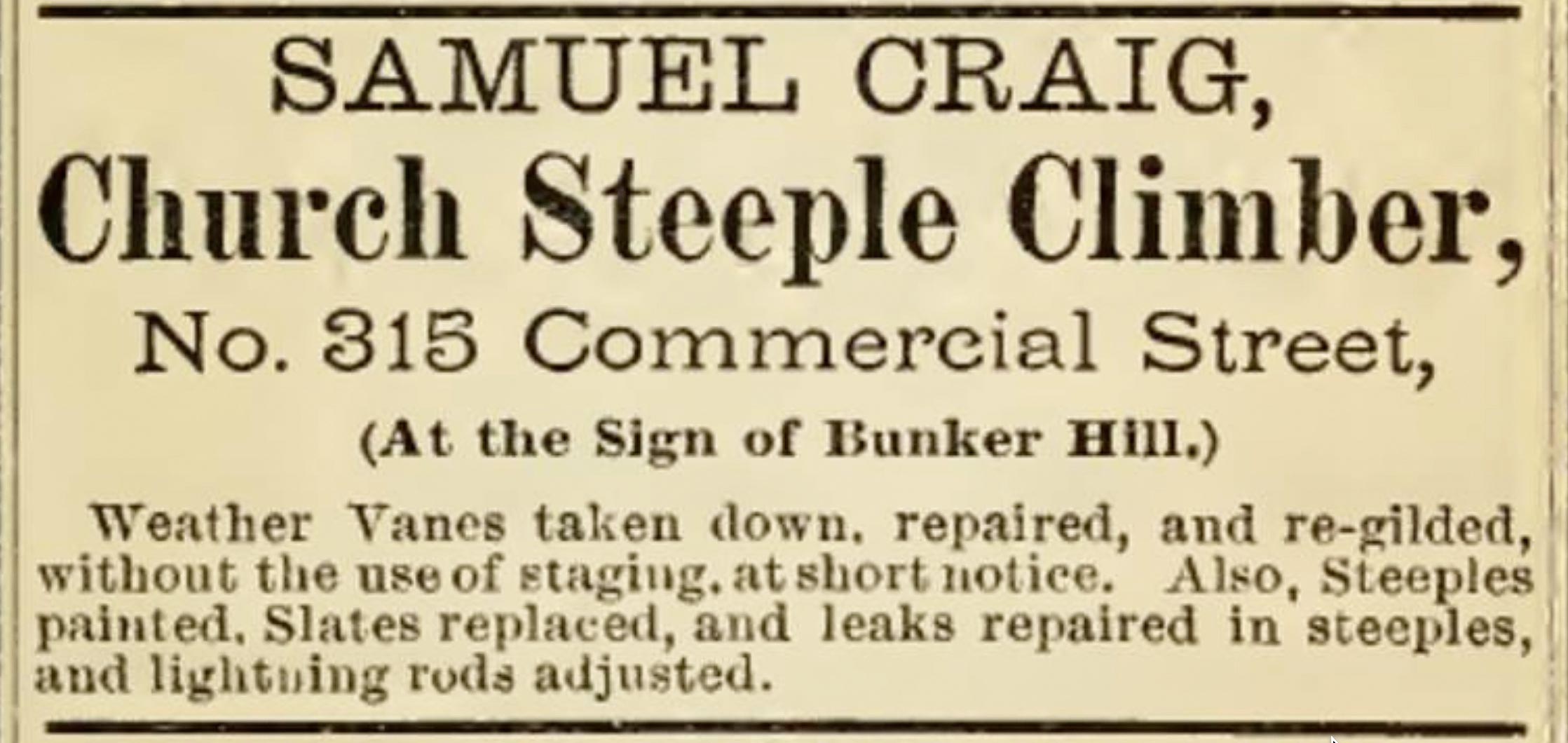

Jewell not only made weathervanes but also mounted them on buildings in the greater Boston area. This was a risky business, and he and an assistant died in 1867 when their 2nd story scaffolding collapsed. I learned that falling more than forty feet is almost always fatal, and I wondered about the men who put vanes on lofty church steeples and found terrifying ads and first-person accounts of dare devil “steeple jacks” who climbed and worked without ropes or any other “safety net” hundreds of feet in the air.

I also found Jewell’s only known trade card, printed in 1866, which has period photographs of his vanes on one side, the only known images of his work and the earliest photos known of American vanes. I also found one of his printed business postcards, which has an engraving of his popular eagle vane on one side.

Boston makers brought the vane trade to New York. Jewell shipped vanes all over the country in the 1860s and had a representative in New York selling his vanes in 1865.

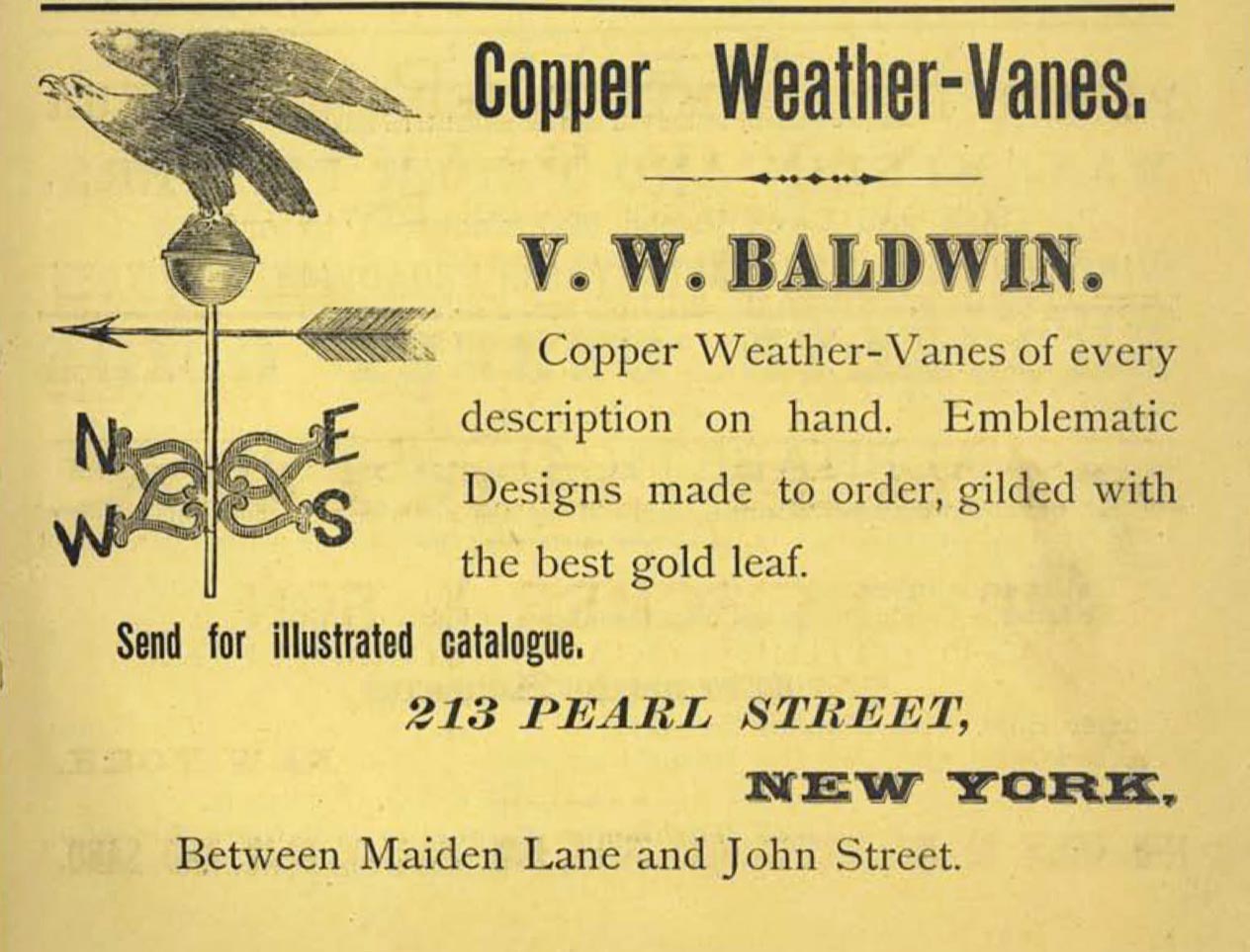

I established that Willet Leander Washburne was the first New York-based vane maker and found proof that he and his brother were making and selling vanes in 1866. I also found a previously unknown New York maker named Vincent W. Baldwin, who advertised his business in 1874.

When I contacted the MFA Boston about their weathervane collection, I discovered that my friend and colleague Sloane Stephens Awtrey, with whom I had worked in the early 1990s at the Shelburne Museum, was researching and cataloging their holdings. We were both excited by the coincidence, and I asked her if she would work with me as my Boston-based research assistant. She knew everyone in the area and had years of museum experience in historical and genealogical research, so she quickly became an invaluable partner.

Figure 12

The Warren Dragon. Artist unidentified. Warren, Pennsylvania, c. 1891. Molded copper with glass eyes. Overall h. 6 ft., 10 in.; dragon 57 x 40 x 6 in. Private Collection. Photograph by Gavin Ashworth; courtesy Allan Katz Americana, Madison, CT.

This monumental dragon was originally commissioned for the Warren Savings Bank, a brick Victorian replica of New York’s Flatiron Building. Depicted crawling up a pole, the beast comes fiercely to life, inviting viewers to envision the dragon in the act of mounting the building.

Figure 13

“The Blériot XI Monoplane,” from the Poland Spring House, Poland Spring, Maine, c. 1909–14. Copper, 10 x 57 ¼ x 55 in. Collection of Michael and Patricia Del Castello, photo Michael Lynberg.

This singular American weathervane is a carefully observed representation of the small, fragile monoplane that pioneering French aviator and inventor Louis Blériot flew over the English Channel on July 25, 1909. Blériot was the first person to fly an airplane over the Channel, and his daring flight made him an international celebrity. The vane was made on commission for the Poland Spring House hotel in Poland Spring, Maine, where it was placed not long after Blériot’s epic flight. The vane is a unique sculptural event, unparalleled in its scale and level of detail. Nothing else remotely like it is known.

I also wrote to Myrna Kaye, the author of the superb 1975 book Yankee Weathervanes, who was still living in Lexington with her son Steve. They invited me to visit. Myrna and I shared our mutual enthusiasm for vanes and their history, and she and Steve graciously offered to lend me her research files, which I, of course, accepted. Myrna had spent considerable time at the Waltham Historical Society, which owns Leonard Cushing’s journals and other key documents, and her notes and transcriptions contributed greatly to what Sloane and I were able to put together.

Pouring over obscure period publications, city directories, and census records, Sloane and I found treasures that added immeasurably to our understanding of early Massachusetts makers and their inter-relations. I knew there were makers at work before the Howards and was thrilled to find a previously undocumented Boson maker named Isaac Tompkins, who was born in 1799 and was probably the earliest commercial vane maker anywhere. He was a friend of the artist and inventor Rufus Porter, who painted miniature portraits of him and his wife in 1820, so we know what he looked like but still have not found a surviving vane by him we can document. Then Sloane discovered that Tompkins had a shop on Union Street in the 1860s, directly across the street from a previously unknown showroom owned by one Alvin Jewell. Surely, the two men knew each other, and I envisioned them dining at what is now the Union Oyster House. Sloane and I hope to find evidence that Tompkins influenced Jewell and other early makers. Stay tuned!

No one had clearly described the making a molded copper vane, so I visited a Vermont foundry owner who still works with sand-casted pattern-based molds and asked Sloane to visit Lee and Jonathan Webber in Groveland, Mass., who own the largest collection of nineteenth century vane molds in the country. The Webbers still use some of them, and Sloane took photos of the duo showing the step-by-step process of hammering sheet copper into cast iron molds and assembling and finishing a vane. That became the last chapter in the book, which was finally sent to the printer in November 2020.

As soon as the book was finished, Emelie and I turned our attention to finalizing object choices, wall texts, and layout of the show, working with the museum’s crack design and exhibition production team. We were still moving things around when the fifty-two vanes and carved patterns started arriving in early June. If you saw the show, you know the results were spectacular.

Figure 16

Exhibition American Weathervanes: The Art of the Winds, American Folk Art Museum, New York, 2021. Photo by Olya Vysotskaya, courtesy American Folk Art Museum.

Wooden weathervane patterns by carved by Harry Leach for Cushing & White, and Cushing vanes for the fox and squirrel. Setter dog pattern collection of Donna and Marvin Schwartz, others private collection.

This project was a team effort, and my hat is off to everyone who helped make it all happen, especially Jane Katcher, the late Myrna Kaye, and Julie Lindberg, the trio to whom I dedicated the book.

But sadly, all things must pass, and, now that the show has closed and the vanes have gone home to their owners, its powerful physical and visual impact will live on only in memory and photos. On the other hand, however, I hope my book will endure as a basic scholarly reference that will expand understanding of the history and artistry of American vanes and undergird further research for many years to come.