Signature Styles:

Friendship, Album, and Fundraising Quilts

Emelie Gevalt

Editor’s Note

The American Folk Art Museum’s Emelie Gevalt curated an exhibition of thirteen signature quilts from the museum’s extensive collection, drawing on the work of past curators Elizabeth V. Warren and Stacy C. Hollander. The show was on view at the museum’s Self-Taught Genius Gallery in Long Island City, Queens, from January to December 2020. Gevalt and the museum kindly allowed Americana Insights to reprint some of the quilts and exhibition text. All the quilts may be viewed on the museum’s website along with a virtual tour of the exhibition, both of which are linked in the online version of this brief.

Overview

By its nature, the signature quilt is meant to be read not only as a whole but also square by square. Although the form is known by various names—including friendship, album, and fundraising quilts—what all of these types share is the composite nature of the quilting project, in which individual signed blocks have been brought together to form a larger design. This type of quilt was often a group undertaking, with each block typically named for, and frequently made and/or paid for by, a different member of a community.

In this sense, the signature quilt holds symbolic value not only as a record of shared creative endeavor, which is the case for many quilts, but also as a legible record of relationships between the quilters and their communities, as well as between the part and the whole. As documents of past networks, such objects extend a sense of interconnectedness into the present, drawing viewers into a web of historical linkages in tandem with the visual interactions between blocks.

Like the systematically articulated branches of a family tree, the signature quilt simultaneously lays out and pulls in, engaging us in a simile between the group’s structure and of the object’s dynamism, as we expand and contract our focus to take in both the large and small.

Origins

The American trend towards signature quilts began in the mid-nineteenth century and was reignited late in the century. Inspiring a fad with numerous variations, the form itself likely developed in part from a fashion for autograph albums, popular in the United States by the early nineteenth century. Similar to the guest book or later yearbook, an autograph album served as a forum for preserving personal connections, collecting inscriptions from friends and acquaintances as mementos of relationships, in keeping with the era’s culture of sentimentality.

The signature quilt takes up the spirit of this social ritual and enlarges it, demanding greater ambition from its participants and a bolder display for its finished product—an expansive bedcover or showpiece that would have a regular presence in a domestic interior, a reminder of community, bound together both literally and metaphorically by connecting threads. Such visual and material symbols would have served as powerful constants during times of familial and social change.

Album Quilts

Album quilts display blocks with an array of patterns, often featuring pictorial appliqué images. Such designs became so popular in Baltimore that the city developed its own distinctive, especially elaborate variation of the trend, sometimes undertaken as an individual, rather than collective, project. Although only some Baltimore-style album quilts bear the names of their makers, others recall the signed examples in their designs.

Some of the most elegant mid-nineteenth-century album quilts were made in Baltimore, typically by members of the Methodist and German Reformed congregations of the city. These quilts are characterized by their elaborate appliquéd pictorial imagery and creative use of fabrics. This variety was facilitated, in part, by easy access to a wide range of imported textiles that came through Baltimore’s commercial harbor.

Scholarship suggests that individuals may have designed and made Baltimore album quilt blocks for purchase and assembly. For example, Mary Heidenroder Simon, who has been identified as the possible designer of a group of album quilts, may well have sold blocks to other quilters. An example from this group (Fig. 1) features similar images—including cornucopias, wreaths, and an eagle—similar to those in a quilt described by an 1850 diarist who recorded a visit to “Mrs. Simon’s in Chesnut [sic] St. The lady who cut & basted these handsome quilts – saw some pretty squares.”

Another group, comprising thirteen related quilts, may have been made by members of Baltimore Hebrew Congregation. Because of their similarities and shared motifs, it is believed that one creative imagination may have designed the quilt blocks, while the quilts may have been completed by different hands. An example (Fig. 2) features several of the recurring elements of this group, including a running elephant and a mounted rider, who has been identified as Captain Samuel Hamilton Walker (1817–1847), Maryland-born hero of the Mexican-American War.

Figure 2

Reiter family album quilt, probably Baltimore, c. 1848–1850. Cotton and wool, 101 × 101 in. American Folk Art Museum, Gift of Katherine Amelia Wine in honor of her grandmother Theresa Reiter Gross and the makers of the quilt, her great-grandmother Katie Friedman Reiter and her great-great-grandmother Liebe Gross Friedman, and on behalf of a generation of cousins: Sydney Howard Reiter, Penelope Breyer Tarplin, Jonnie Breyer Stahl, Susan Reiter Blinn, Benjamin Joseph Gross, and Leba Gross Wine, 2000.2.1. Photograph courtesy of American Folk Art Museum/Art Resource, NY.

Friendship Quilts

Friendship quilts often consist of blocks designed after a common pattern, often differentiated by a variation in color or the inclusion of individual signatures. Many friendship quilts were conceived as gifts, such as the Dunn album quilt and the surprise quilt presented to Mary A. Grow. Such examples underline the commemorative or celebratory purposes fundamental to the form, across its variations, often made to mark an important event, such as a marriage or a departure from a community.

An inscription on the Dunn quilt (Fig. 3) states that it was presented in 1852 to Mr. (probably Reverend) and Mrs. Dunn by members of the Sewing Society of the Methodist Episcopal Church of Elizabethport, New Jersey. The quilt was probably made to commemorate Dunn’s role in the establishment of a new Methodist congregation in Elizabeth.

Figure 3

Sewing Society of the Fulton Street United Methodist Episcopal Church, Dunn album quilt, Elizabethport, New Jersey, 1852. Cotton and ink with cotton embroidery, 100 × 99 ¼ in. American Folk Art Museum, Gift of Phyllis Haders, 1980.1.1. Photograph by Gavin Ashworth. Photograph courtesy of American Folk Art Museum/Art Resource, NY.

Although the occasion celebrated by the Grow quilt (Fig. 4) is unknown, each block bears the name, inscribed in ink on the reverse, of a friend who contributed to this “surprise” for the recipient. Mary Ann Hackett (1817–1896) was born in England and moved with her family to New York State, where she married William A. Grow, a minister. They subsequently moved to Plymouth, Michigan, where this quilt was made, and then to Pennsylvania. The quilt was obviously cherished over the years and descended in Grow’s family.

Figure 4

Surprise quilt presented to Mary A. Grow, Plymouth, Michigan, 1856. Cotton with ink and embroidery, 87 × 82 ½ in. American Folk Art Museum, Gift in memory of Margaret Trautwein Stoddard and her daughter, Eleanor Stoddard Seibold, 2003.2.1. Photograph courtesy of American Folk Art Museum/Art Resource, NY.

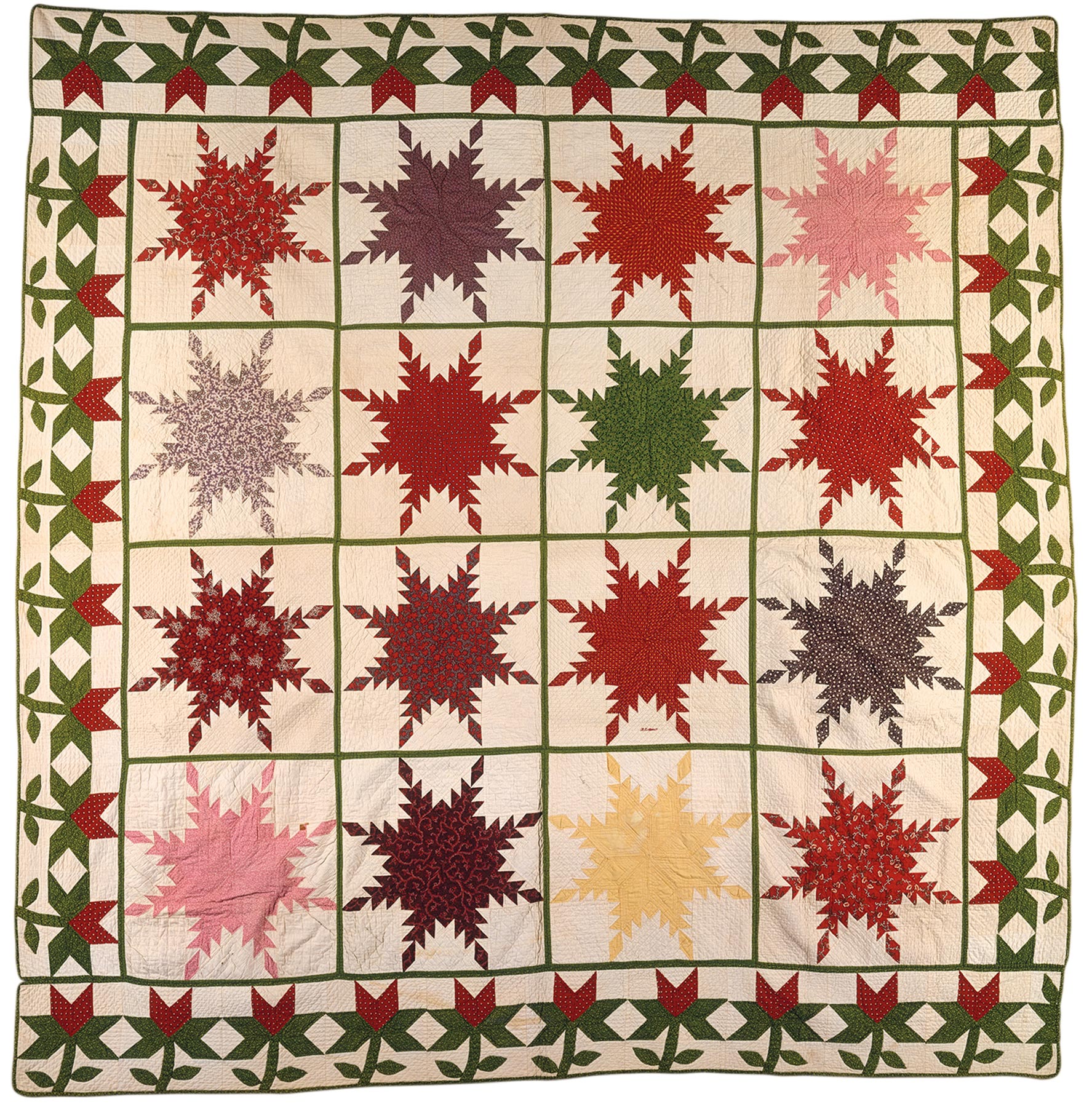

In an exuberant example of a friendship quilt, made by unidentified Pennsylvania German artists, each one of the blocks holds sufficient visual interest to comprise a quilt pattern of its own (Fig. 5). Together, they constitute a virtuoso display of color, design, and creative imagination.

Fundraising Quilts

Fundraising quilts were assembled to benefit a charitable cause. Each participant made a contribution—for instance, a dime—in exchange for the inking or embroidery of their name upon a square.

An example of an early-twentieth-century fundraising quilt commemorates Admiral George Dewey (1837–1917), hailed as a naval hero of the Spanish-American War of 1898 (Fig. 6). Although no specific connection has been established between Dewey and the Indiana church for which the quilt was made, he was a popular figure, and multiple quilt patterns bearing his name were published in the early twentieth century.

The quilt is thought to have been purchased in Indiana not long after its making by a Vermont-based family, the Griffins, who may have been especially drawn to the Dewey theme because of the admiral’s Montpelier origins. In an amusing quirk—perhaps the quiltmaker’s error—the D’s have been incorporated backwards relative to the orientation of the central inscription.

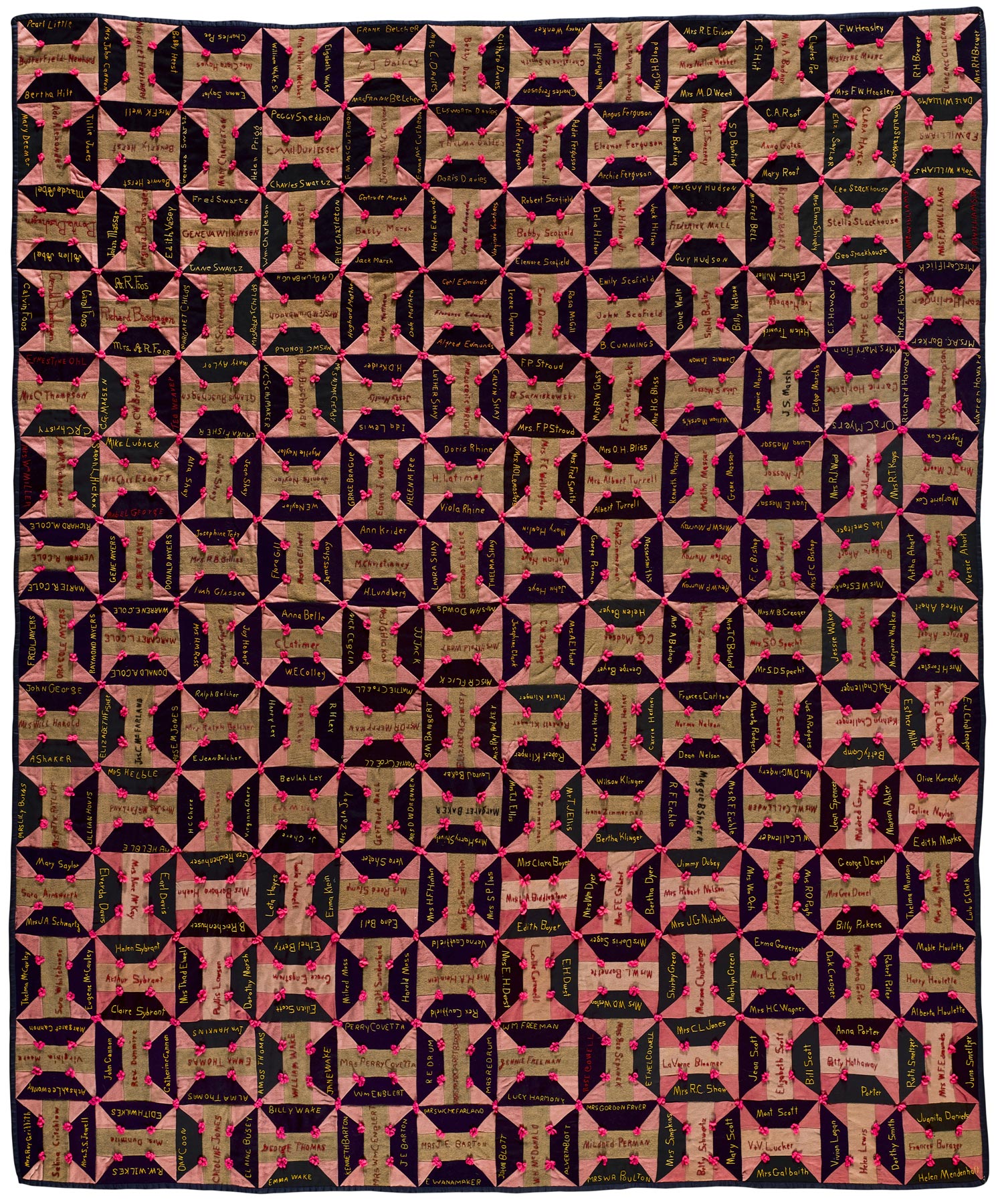

With its block pattern of repeating spools, a 1930s quilt from northeastern Ohio makes a visual pun on the quantity of thread and repetitious labor involved in such a project (Fig. 7). Although simple in concept—making use of just three colors and a single block design, tied together with bright pink knots—the offsetting black background and the dynamic alternation of spool direction make for an especially appealing result. Made during the Great Depression for the purposes of church fundraising, the quilt not surprisingly took top prize at a local fair. It was raffled off to the Massar family, whose name can be found multiple times across the surface of the quilt, memorializing their engagement with the church community.

Figure 7

Ladies’ Aid Society, McKinley Community Church, McKinley Community Church signature quilt, Warren, Ohio, 1935. Wool with wool yarn and embroidery thread, 74 ½ × 86 in. American Folk Art Museum, Gift of Ivan Massar, 2007.2.1. Photograph by Gavin Ashworth. Photograph courtesy of American Folk Art Museum/Art Resource, NY.

This quilt can be read as a visual pun, its reiterated spool block pattern making a playful reference to the quantity of thread and the repetitious labor involved in such a project. Although simple in concept – making use of just three colors and a single block design, tied together with bright pink knots – the offsetting black background and the dynamic alternation of spool direction make for an especially appealing result. Made during the Great Depression for the purposes of church fundraising, the quilt not surprisingly took top prize at a local fair. It was raffled off to the Massar family, whose name can be found multiple times across the surface of the quilt, memorializing their engagement with the church community.