Rufus Porter in Context

Artist-Inventors and Itinerants in America

Laura Fecych Sprague

Editor’s Note

Once called the “Yankee Da Vinci,” Rufus Porter was an itinerant portrait painter and muralist, a publisher and author, an inventor of mechanical improvements, and an impresario who engineered an airship that promised to fly gold rush prospectors from New York to California in three days.

The recent book Rufus Porter’s Curious World: Art and Invention in America, 1815–1860, co-edited by Laura Fecych Sprague and Justin Wolff (Fig. 1), is organized around major themes in Porter’s life. In this short piece, Sprague offers a taste of the book by focusing on artist-inventors and itinerant artists. She has selected several examples to help place Porter’s pursuits and interests into the larger cultural context of antebellum America.

Artist-Inventors

Robert Fulton (1765–1815), like Rufus Porter, was an ambitious man with many talents. He started his career as an artist but is most famous today as an engineer and inventor who developed the first commercial steamboat. Fulton also wrote an important treatise on the improvement of canal transportation and built the world’s first practical submarine.

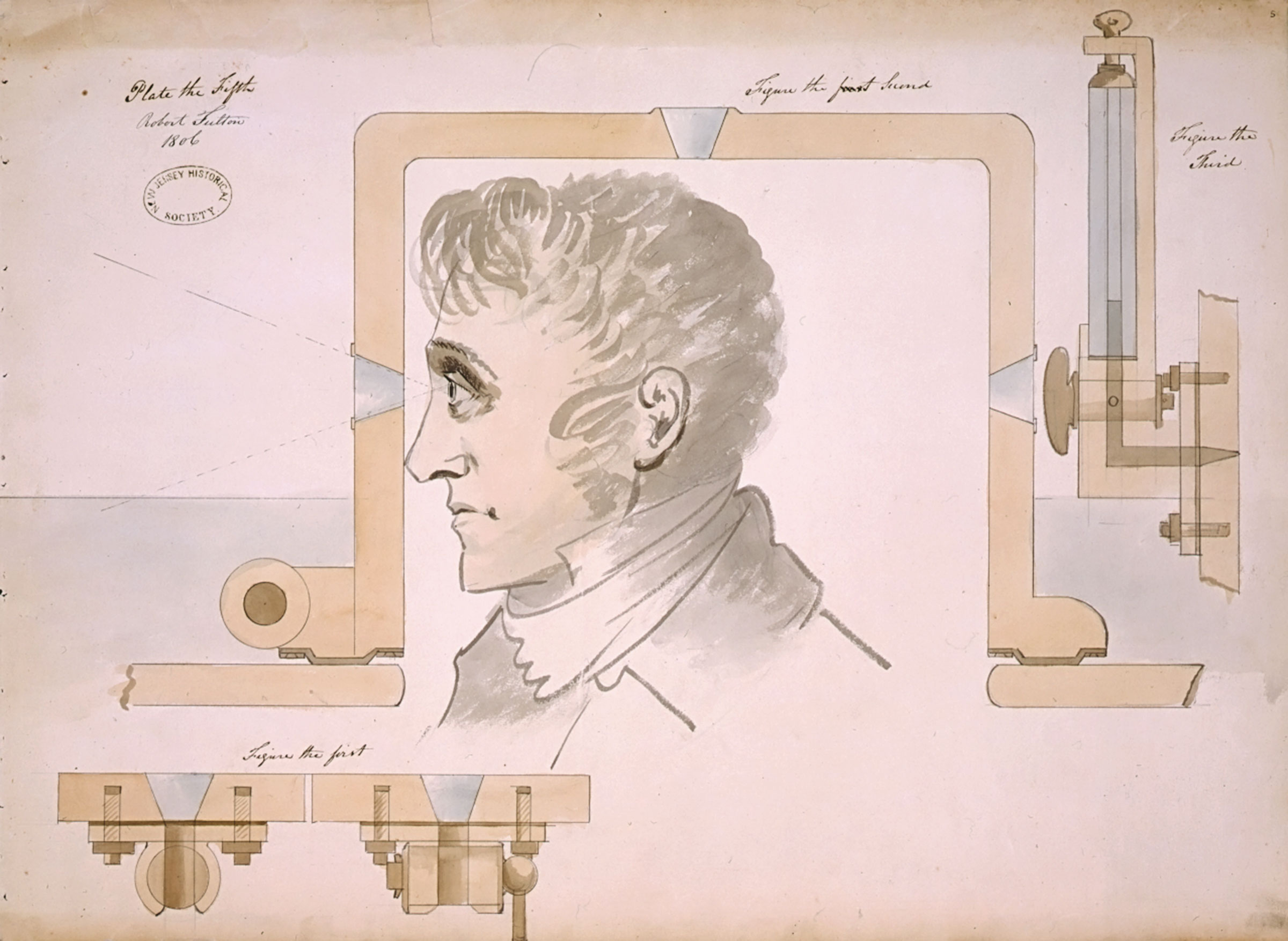

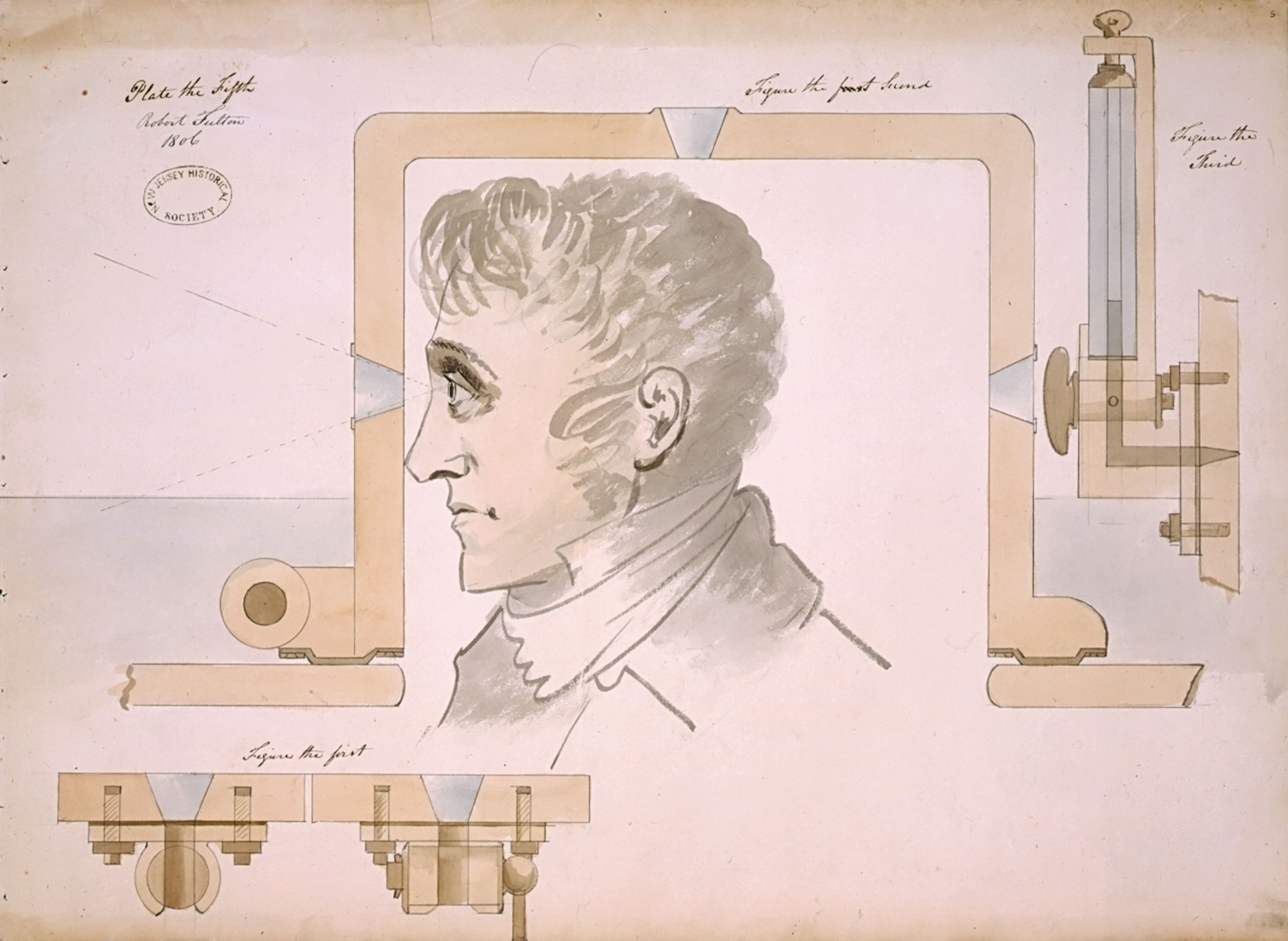

Fulton excelled as a draughtsman, producing remarkable sketches and diagrams of his various inventions. In 1800, at the behest of Napoleon, Fulton developed the Nautilis, an early submersible vessel, and by 1806, during the Napoleonic Wars, he was designing and promoting a system for submarine and torpedo warfare. Among the sixteen drawings collected in a pamphlet titled Submarine Vessel, Submarine Bombs and Mode of Attack was a diagram depicting conical glass sections to be inserted into the conning tower of a vessel (Fig. 2). It served a dual purpose: it let light into the interior and functioned as a primitive periscope, permitting the captain to observe his surroundings from safety. A superb example of spatial thinking, it illustrates how artist-inventors, such as Fulton and Rufus Porter, designed systems on multiple scales.

Benjamin West (1738–1820) was born in Pennsylvania, where he claimed to have taught himself how to paint and befriended Benjamin Franklin. In 1760, he traveled to Europe and eventually settled in London, where he became a famous painter and helped establish the Royal Academy. West obligingly instructed many American artists who visited London, including Charles Bird King (1785–1862) and three artist-inventors—Fulton, Samuel F. B. Morse (1791–1872), and Henry Sargent (1770–1845). He painted Fulton’s portrait in London while the latter was in Europe to develop new technologies for the French and British governments (Fig. 3). The dramatic likeness romanticizes the inventor, portraying him as a fiery, intense genius. A torpedo, another of Fulton’s inventions, explodes in the background.

Before becoming inventors, both Fulton and Porter painted miniature portraits for a diverse clientele. Miniature portraits first gained popularity in America in the 1760s. Beloved keepsakes, the smallest were typically housed in lockets, bracelets, or brooches with glass coverings; miniatures on ivory were especially precious. Fulton, who learned to paint on ivory as a young man while working for a Philadelphia jeweler, made especially elegant miniatures featuring delicate but expressive brushwork. A watercolor-on-ivory portrait of his wife, Harriet Livingston Fulton (1783–1826), niece of his partner Robert R. Livingston (1746–1813), depicts her seated in a fashionable Empire-style chair wearing a sophisticated and costly dress (Fig. 4). Fulton met her while traveling the Hudson River in his famed steamboat, the Clermont.

Itinerant Artists

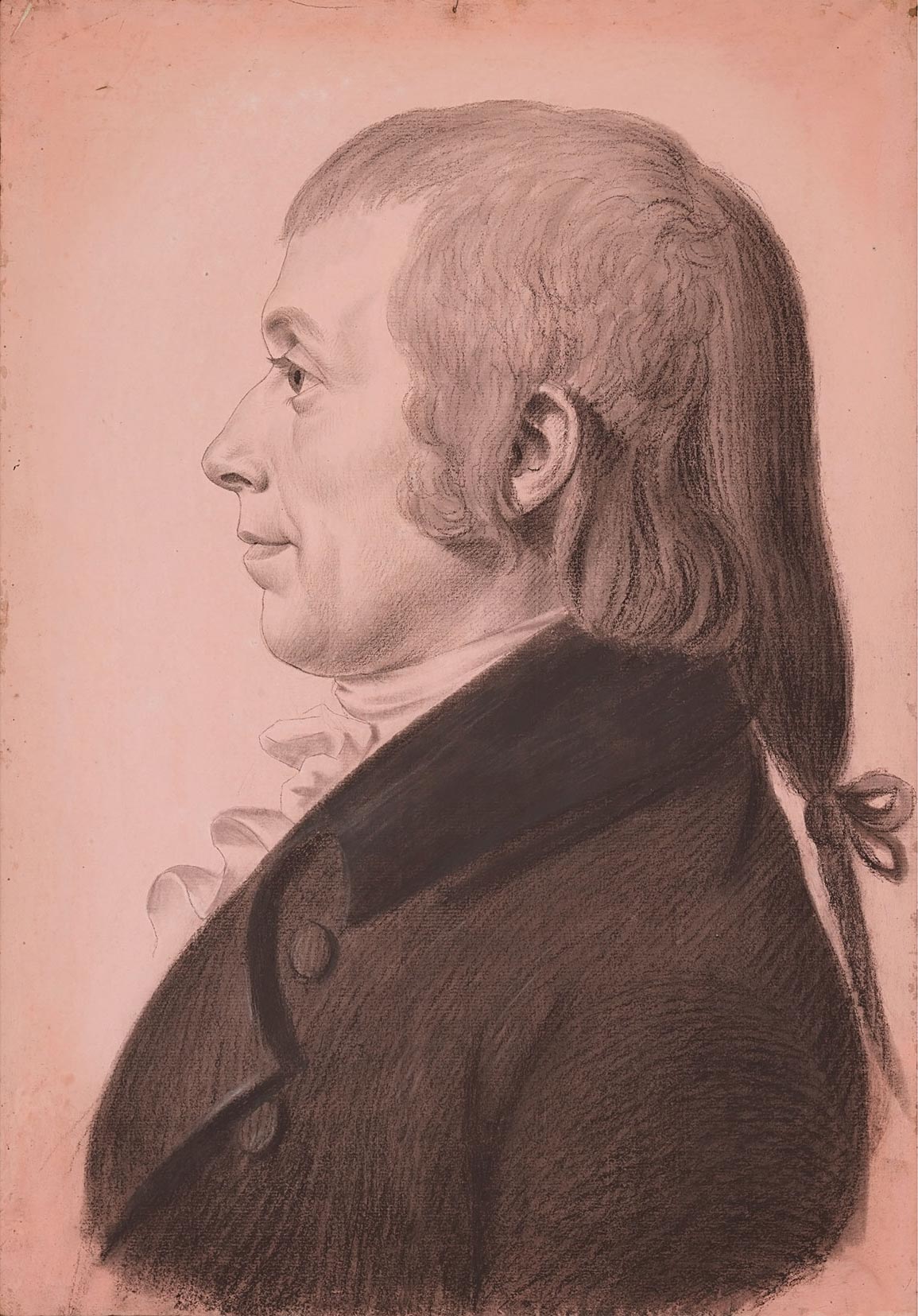

Charles Balthazar Julien Févret de Saint-Mémin (1770–1852) emigrated from Paris after the outbreak of the French Revolution. Once in the United States, the aristocratic Saint-Mémin, who had practiced art as a gentlemanly pastime, turned his hobby into a profession. From 1793 until his return to France in 1814, he traveled through the country making profile portraits with the aid of a mechanical device called a physiognotrace, which allowed artists to precisely trace a sitter’s full-size profile. Saint-Mémin completed his portraits by filling in the features with crayon. Though from a very different background than Rufus Porter and other commercial portrait painters, Saint-Mémin modeled the practices of later itinerant artists in America.

Temperance Lee (1769–1845) and her husband, Silas (1760–1814), lived in Pownalborough (now Wiscasset), Maine, where they were involved in community activities. Silas, a graduate of Harvard College, served as overseer at Bowdoin College, founded in Brunswick, Maine, in 1794, and served in Congress from 1799 to 1804. In 1805, Temperance helped establish the Female Charitable Society, one of the oldest women’s clubs in the United States. The society supported local families in need with clothing and basic provisions and also encouraged their moral and religious development. Saint-Mémin drew the Lees’ portraits while they were in Philadelphia (Figs. 5, 6). In his likeness of Temperance, one of the few women he ever depicted, he captures an alert and handsome figure, ornamented by jewelry, a headdress, and stylish fichu or ruffled collar.

In Portland, Porter may have crossed paths with John Brewster, Jr. (1766–1854), the accomplished itinerant portraitist. A deaf-mute from birth, Brewster was the son of a respected Connecticut doctor who encouraged him to learn to read and write. Exhibiting a talent for painting, Brewster was professionally trained, and his early portraits reflect the style of prominent Connecticut artists, such as Ralph Earl (1751–1801). Brewster lived for extended periods with his brother in Buxton, Maine, and traveled to the coastal towns of Portland, Saco, and Kennebunk, where he met the demands of a wide range of clients. His bust length oil-on-canvas portrait of Moses Quinby (1756–1857) is one of several that he painted of Portland sitters during the first decade of the nineteenth century (Fig. 7). Brewster depicted Quinby in a clear, forthright, and focused way, typical of his style.

Quinby studied at Phillips Exeter Academy before attending Bowdoin College. At his 1806 commencement exercises, he delivered an essay on the solar system. After his graduation, he studied law with Stephen Longfellow (1775–1849), father of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807–1882), who would become America’s great nineteenth-century poet. When Quinby’s father died that year, Moses inherited his large estate. Moses’s portrait was one of three illustrated in a 1915 family genealogy, Genealogical History of the Quinby (Quimby) Family in England and America, by Henry Cole Quinby. The others depict Anne Titcomb (1789–1859), whom he married in 1809, and Levi Quinby (1727–1828), his younger brother.

Charles Bird King (1785–1852) studied portraiture in New York and, later, with Benjamin West at the Royal Academy in London. On his return to the United States in 1812, he spent seven years traveling the East Coast in search of portrait commissions. In 1819, he opened a studio and gallery in Washington, DC, where he painted many prominent political figures and over one hundred portraits of visiting Native American chiefs. In The Itinerant Artist, one of the era’s most iconic genre paintings, King draws on his experiences (Fig. 8). It depicts a portrait painter, possibly King himself, trying to paint a likeness of the proud lady of the house while getting presumptuous criticism from an old woman, perhaps the sitter’s mother. Unlike established artists, who worked alone in their studios, itinerant painters, such as Porter, coped with or embraced such onlookers. In this family, however, only the women and children appear interested, while the father heads outdoors to hunt.

Born in Parsonsfield in western Maine, John Usher Parsons (1806–1874) graduated from Bowdoin in 1828. A driven evangelist, Parsons became a missionary and pastor, traveling the country to preach. An active publisher, Parsons, like Porter, compiled religious tracts. Parson’s obituary described him as “a man of intellectual power, of enterprising spirit, [and] of constant activity and eminent devotion.” Between 1834 and 1838, when Parsons was recuperating from an illness, he produced about a dozen portraits. Although he was a self-taught artist content to paint in a flat, planar style, Parsons employed symbolic references associated with fine art. In a self-portrait, he shows himself in a study surrounded by the books, some with Latin titles, that sustained his “intellectual power” (Fig. 9). Moreover, by including a seaport in the background (possibly a panoramic wall mural), Parsons both references some of the places where he preached and connects himself to the itinerant networks shaping the young nation at the time.

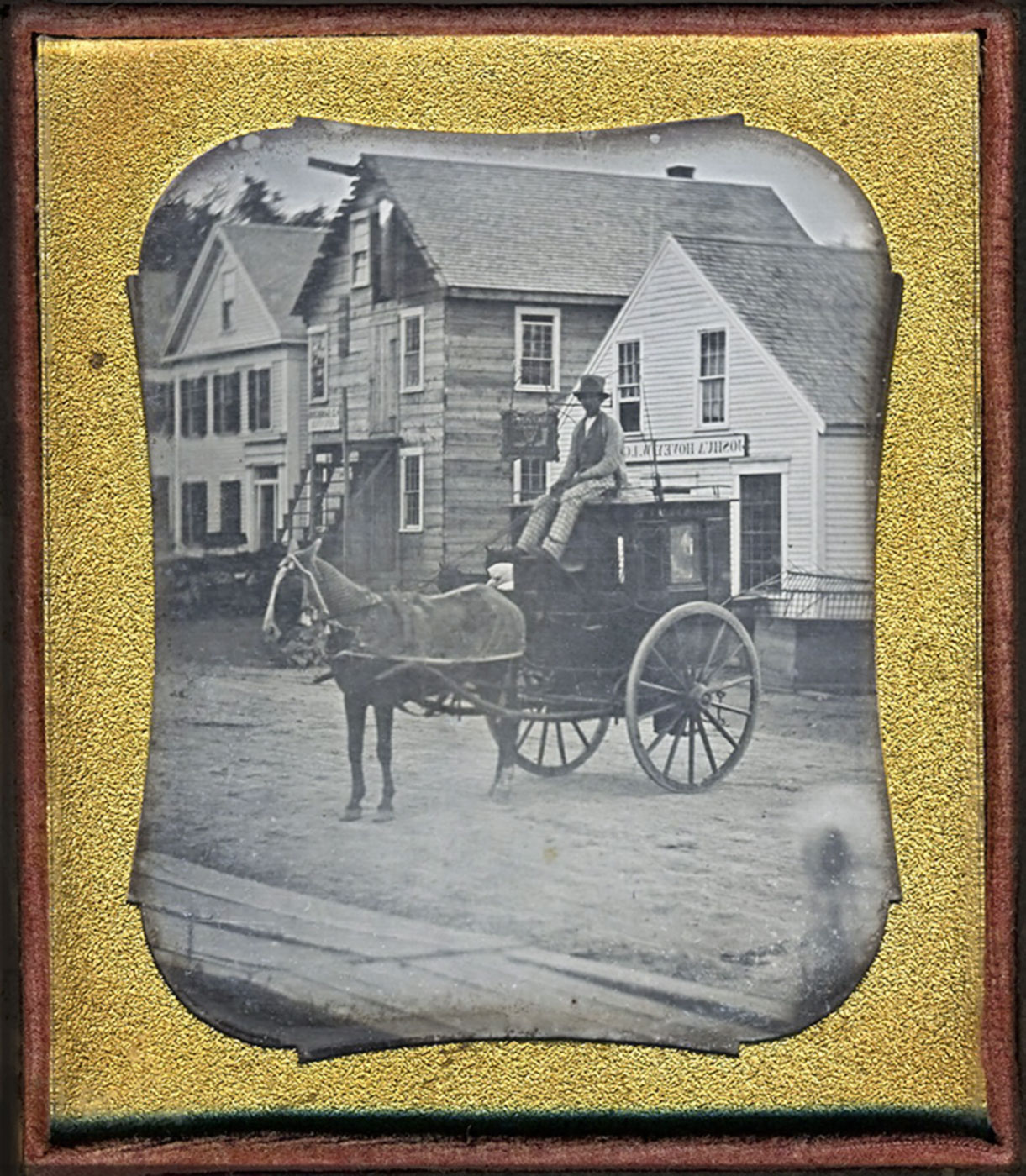

By 1840, Rufus Porter had turned his attention to the pursuit of mechanical improvements and settled in New York City. As photography emerged in the United States in the 1840s as an efficient means for creating likenesses, the work of itinerant artists declined. The genre of occupational daguerreotypes, depicting tradespeople—cobblers, carpenters, and blacksmiths with the tools of their trade or goods that they made—help document many different types of Americans. An example depicting Joshua Hovey (1808–1899), a Massachusetts shoemaker, grocer, and merchant, references itinerancy and peddling in different ways (Fig. 10). For one, the unknown photographer may have traveled from town to town with his camera, making and selling his images. Hovey was also a man on the move, willing to bring his services to various towns along the Merrimack River in Massachusetts and New Hampshire. In the 1820s and 1830s, Porter had operated along many of the same geographical networks as Hovey, selling miniature portraits and developing commercial plans for his various inventions.